![[UNAC]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Image-empty-state.webp)

Roméo Dallaire served 35 years with the Canadian Armed Forces, including his role in 1993-94 as Commander of the UN Assistance Mission in Rwanda. [UNAC]

Earlier that day, a separatist cell of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) had kidnapped British Trade Commissioner James Cross. In doing so, the weeks-long ordeal dubbed the October Crisis (also known as the FLQ Crisis) had begun.

And Dallaire would soon find himself in the centre of an unfolding drama.

Though born in immediate postwar Netherlands, the young officer had been raised in Quebec from an early age, later bearing witness to the Quiet Revolution—a period of rapid socio-cultural change across the province—before joining the largely Anglocentric military in the early 1960s.

It was almost as if Dallaire had two identities, or at least that was how it came across whenever he and fellow trainees visited Montreal on the weekends.

“Of course, we would run into Quebec nationalists,” the now-bestselling author wrote in his book Shake Hands with the Devil, “who would engage us in heated debate about joining that bastion of anglophonie, the Canadian Armed Forces.”

On July 24, 1967, Dallaire sat down to watch television with his comrades when Charles de Gaulle, then-president of France and a long-controversial figure, declared “Vive le Québec libre!” (“Long live free Quebec!”) during an official visit to Canada.

“The crowd on TV roared with obvious delight while the mess went dead silent,” Dallaire remembered, “except for muffled scraping as people shifted in their seats to stare at the only Quebecker in the room…. Nobody came up to me, nobody talked to me. I was part of the evil empire that was threatening to tear the country apart.”

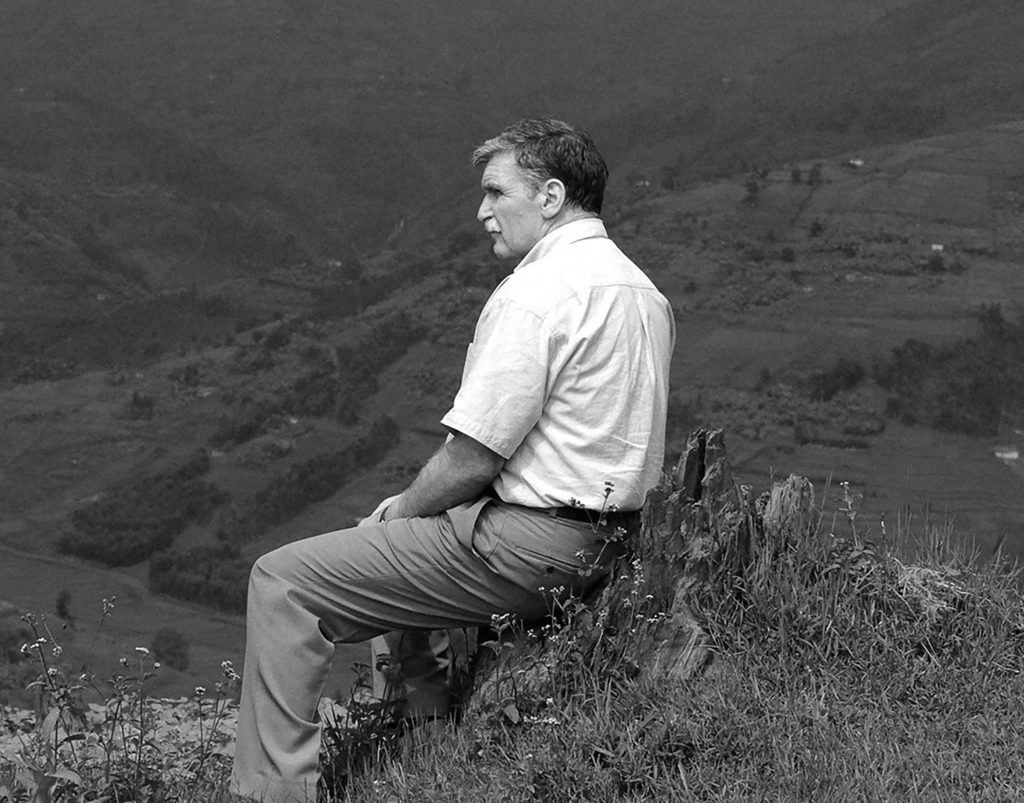

In the years following Roméo Dallaire’s retirement, he has dedicated himself to eradicating child soldiers in conflict zones around the world. [Peter Bregg]

That moment arrived on Oct. 5, 1970, exacerbated by the kidnapping of Quebec Labour Minister Pierre Laporte five days later. In response, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act on Oct. 16—54 years ago—suspending peacetime civil liberties, permitting detention without habeas corpus or legal representation, and directing censorship of the press.

Alas, it was too late for Laporte, who, the next day, seized an opportunity to escape only to be murdered in the process. The FLQ’s four-member Chénier Cell dumped his body in a beat-up blue Chevrolet and abandoned it within sight of Canadian Forces Base St. Hubert. The discovery provoked outrage across the country, coinciding with Dallaire’s deployment to Quebec City with 41 soldiers under his command.

“Our rules of engagement included the use of live ammunition to prevent acts of insurrection,” he wrote. “This situation presented me with one of the most difficult ethical and moral dilemmas of my military career. Members of my own extended family, as well as friends from my old neighbourhood, were supporting the separatist movement. At any time I might see faces I knew in the hostile crowds…. How would I react? Could I open fire on members of my own family?”

Tasked with protecting government buildings and provincial politicians, Dallaire spent the following three months carrying out six-hour stints of duty, mostly in the “bone-chilling” cold of Quebec’s fall and winter with 20-minute breaks to warm up inside. “We took a fair amount of flak from separatist supporters who jeered and hassled us,” he recalled, a hostility that extended to many francophone soldiers.

“Some of [the French-speaking contingent] came from pro-separatist families who viewed them as traitors; at the same time, they were being branded by some of their [anglophone] comrades as untrustworthy ‘frogs.’” A Québécois Catch-22.

Thankfully for these troops, not least Dallaire, the October Crisis didn’t escalate further, and the army was spared from using lethal force. Nevertheless, there had been close calls, especially in November when a soldier under the lieutenant’s command was beaten and hospitalized in a random act.

Dallaire was on the cusp of responding when “the police, who were monitoring our radio frequency and were desperate for a little action…came barrelling down the narrow street [in their police cars].” The perpetrator was promptly apprehended.

The ethical and moral dilemmas he faced during the October Crisis served as ominous foreshadowing for what lay ahead.

On Dec. 3, 1970, military intelligence zeroed in on James Cross’ location, and after negotiating with the militants, the British diplomat was released. He had spent some 60 days in captivity, while the captors themselves spent years of exile in Cuba as part of the exchange. Laporte’s kidnappers, meanwhile, were behind bars by the end of the year. Their prison sentences ranged from eight years to life.

For Lieutenant Roméo Dallaire, the ethical and moral dilemmas he faced during the October Crisis served as ominous foreshadowing for what lay ahead—albeit of a far different nature and, indeed, on an immeasurably more horrendous scale.

Between April 6 and July 16, 1994, some 800,000 Rwandans, mainly of the Tutsi ethnic group alongside moderate Hutu people, were murdered in a genocide. Then a major-general and force commander of the United Nations peacekeeping mission in the central African country, Dallaire, bound by politically motivated restrictions, had little choice but to watch impotently as UN failings played out before him.

The retired soldier and former Canadian senator has since recounted what he lived through during the October Crisis and the Rwandan Genocide, in Shake Hands with the Devil.

Advertisement