In 1951, Ottawa was making plans for peacetime compulsory military service

Officers from the first French-Canadian battalion formed under conscription pose for a group portrait. [Harry Richards/LAC/3405277]

Conscription—compulsory enlistment for state service, typically in the armed forces—has been one of the most divisive issues in Canada since the Great War.

Prime Minister Robert Borden pushed through the Military Service Act in 1917 and promised at least 100,000 conscripts to reinforce the hard-pressed Canadian Corps. Francophones were outraged, as were farmers, labour organizations and ethnic groups. But Borden persisted, won the general election in December 1917, and although only 24,000 conscripts reached the front before the Armistice, they kept the Corps almost up to strength through the vicious fighting of the Hundred Days from August to November 1918.

Prime Minister Robert Borden visits a wounded man at a hospital near the Western Front in March 1917. [LAC/PA-000880]

History repeated itself in the Second World War. Prime Minister Mackenzie King and Conservative leader Robert Manion had both promised before the outbreak of war that there would be no conscription in the event of war, pledges aimed primarily at Quebec. But by May and June 1940, with Nazi Germany now controlling most of Western Europe, those promises meant little.

In June, King had Parliament pass the National Resources Mobilization Act that instituted conscription for home defence.

Politicians had tried desperately to avoid imposing it.

By November 1944, there were 60,000 NRMA soldiers in Canada, at a time when the battles in Normandy and on the Scheldt had resulted in heavy casualties and a shortage of infantrymen. The army brass said there were no other infantry reinforcements to draw on and King, faced with what he thought of as a revolt of the generals, reversed his course on conscription for overseas service and directed that 16,000 NRMA men, or Zombies as the public derisively called them, be sent overseas.

First Canadian Army was largely out of action from November to early February 1945 and that eased the manpower problem. So too did the few thousand conscripts who reached the front before the German capitulation.

To the planners, the answer was conscription.

Whatever else it was, conscription was demonstrably a persistently divisive issue across the nation and the politicians had tried desperately to avoid imposing it. But the generals and their staff officers were not happy with their political masters on this question. At the very end of the Second World War, the general staff in Ottawa produced plans for peacetime compulsory military service.

Then during the Cold War of the early 1950s, when Canada was fighting in Korea, sending a brigade group to NATO in Europe, and rearming as fast as possible, active and retired generals urged the government to implement conscription to help defend North America and Europe against the Soviet Union.

On March 23, 1939, five months before Nazi Germany invaded Poland, students from Université de Montréal staged an anti-conscription demonstration at Champs de Mars, a former military parade ground in Vieux-Montréal. The sign reads “Pas de conscription. La jeunesse veut la paix” (No conscription. Youth want peace). [Montreal Gazette/LAC/3193209]

As the Second World War drew to its conclusion, the planners at army headquarters in Ottawa were considering the future. The new United Nations had plans for collective security and the expectation was that Canada would be expected to contribute military force to such efforts. What was the best way to raise such soldiers? To the planners, the answer was conscription.

Compulsory service was fair, they said. It would improve the fitness of the country’s young men and it would teach civic virtues to youth who did not seem interested in such ideas.

Plan G, so called because it was the seventh such plan developed by headquarters staff, was presented to the defence minister in late June 1945. It envisaged a peacetime regular army of 55,788, organized as a brigade group with additional men handling such tasks as research and development, administration and training.

To sustain it, 48,500 youths aged 18½ to 19½ would be called up at four-month intervals for a year of training. That would be followed by a period of obligatory service in the reserves. Plan G would create a trained force of two corps with six infantry divisions and four armoured brigades.

This scheme overlooked a few points. First, the air force and the navy wanted nothing to do with conscription and were quick to point out that any compulsory scheme was unlikely to be acceptable to the politicians. They were correct.

When King learned of Plan G in early August 1945, he was furious, calling it “perfectly outrageous” and adding that he “resented strongly the postwar proposals based on the needs of another major war and the necessity of being in readiness for it.”

A few days later, the Cabinet, as King put it, “decided strongly against beginning any compulsory training.”

Conscription was an absolute non-starter for the politicians. They remembered the crisis of 1917, the fights over the conscription plebiscite of 1942 and the great crisis of November 1944. Why the army staff planners did not understand this remains unclear. But change was coming to headquarters.

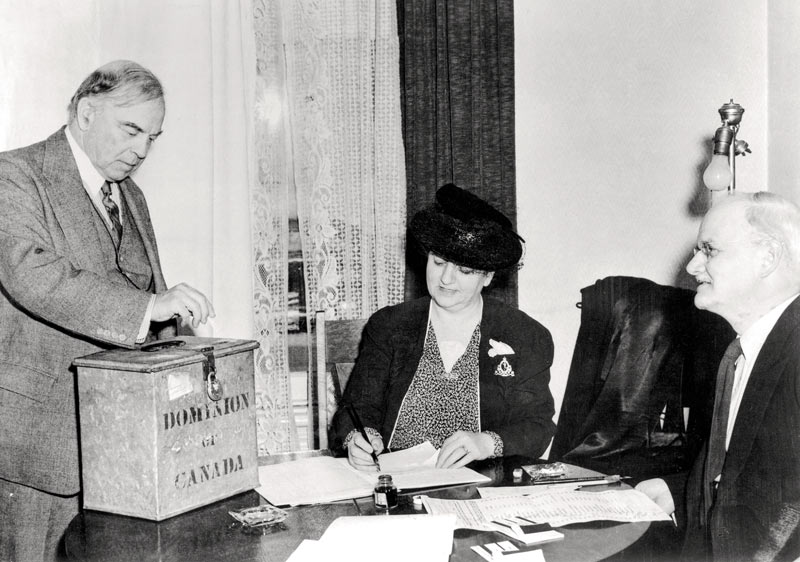

Mackenzie King casts his ballot in a plebiscite on the introduction of conscription for overseas military service on April 27, 1942. [LAC/3193315]

Shortly after Plan G was shot down, Lieutenant-General Charles Foulkes arrived at army headquarters to become chief of the general staff. Foulkes was no great battlefield commander, but he had sensitive political antennae and he would never have proposed such a plan to the ministers only months after the conscription crisis had divided Canada and nearly destroyed King’s government. He might have believed that compulsory service was the best and fairest way to create an army, but Foulkes certainly understood that August 1945 was the wrong time to ask the government to implement it.

The intensifying Cold War changed some minds about how to raise military manpower. Not King’s mind, however.

When the United States began to move toward conscription again in March 1948, King, just months away from retirement, warned his ministers against contemplating such measures. Even if Canada joined the mooted North Atlantic pact, “certainly there would be no commitment of any kind” for compulsory service.

Louis St. Laurent, King’s successor as prime minister, was a very different man. He wanted Canada to play a positive role in the world and, while he was a francophone, he could foresee situations in which conscription might be necessary. If it was, his government would move to implement it.

In 1948, when a labour organization asked for a pledge not to impose conscription in any future war, St. Laurent’s reply was clear: The time might come when the Russians would have to be told that the limit had been reached.

When the Korean War broke out in June 1950, Canada began to re-arm in a serious way and to deploy troops to serve in Europe and fight in Korea. That raised concerns about where more soldiers would be found and the defence minister, Brooke Claxton, had to tell his fellow ministers that he was confident he could raise the initial forces and sustain them with volunteers and without conscription.

A First World War veteran, defence minister Brooke Claxton visits the troops in Korea. [Legion Magazine Archives]

Proponents of conscription, however, were beginning to be heard in the ranks of the Canadian Legion and in speeches from retired general Harry Crerar. But opinion polls demonstrated that a majority of francophones in Quebec opposed sending troops to Korea or Western Europe. That was worrisome to the supporters of compulsory service.

However, Maclean’s columnist Blair Fraser wrote in November 1950 that “evidence continues to mount that Quebec is not so firmly and deeply anti-war as it used to be. No one has suggested that Quebec would go for conscription but there are signs that the old hysterical fear of it has calmed down a bit.”

Whatever Quebecers may have thought, pro-conscription talk in the country was increasing and the St. Laurent government was beginning to take steps to make conscription possible, if it became necessary.

Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent pays a visit to 3rd Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment, at a rifle range in Korea in March 1954. [LAC/4929234]

While some supported conscription and others opposed it, “So far as I am concerned,” St. Laurent told the House of Commons in February 1951, “this is not a matter which can or should be decided on sentimental grounds. It is one which should be decided on its merits…and with regard to what will make for the efficiency and the effectiveness of our contribution to the joint efforts which have to be put forth.”

A few weeks later, a newly created National Manpower Council met in Ottawa and heard the minister of labour, Milton Gregg, say that the prime minister had made clear that the government “would take such compulsory steps as are necessary” to find men for military service. The council was then advised that plans were in hand for a national registration. The registration cards were soon printed.

The same month Claxton told a journalist friend “there would be no repeat on the conscription controversy. The cabinet has decided that there should and will be overall conscription on the day that actual war breaks out.” Claxton added that the decision was largely a demonstration of confidence in St. Laurent by Quebec. “With this, prime minister,” he stated, “we can do anything in Quebec.”

War with Russia did not break out and a national registration and compulsory military service were not implemented. The army brain trust, past and present, however, still wanted compulsory service.

Crerar continued to write articles and make speeches across the country calling for conscription. More seriously, Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds, the new chief of the general staff, told Claxton in May 1951 that, without it, Canada could not meet its commitments in the event of a major war. There were already problems in maintaining the units in Korea, a national registration would take time, and specialists were certain to be in short supply. Claxton indicated that if it became necessary, he would support conscription, something he repeated to the Conference of Defence Associations in November 1951.

Some of the allies complained that Canada was a laggard.

But Simonds remained convinced that compulsory service was necessary. After the Korean armistice, he told a “private” army gathering in Saint John in June 1954 that his view and that of the “vast majority of Canadian officers” was that every youth should receive two years of military training. For this he was reprimanded by Claxton.

The next year, Simonds addressed a Canadian Club of Montreal gathering and again called for compulsion. “A system of compulsory military training would be good for the boy, for the army, and for the country.” Simonds was reprimanded again, and he soon retired as chief of the general staff. He continued his efforts, writing and speaking out for conscription.

The generals may have been right that the country needed conscription. Canada and Iceland were the only NATO nations without compulsory service and some of the allies complained that Canada was a laggard and not doing its share.

The St. Laurent government had made clear that it would act in the event of war with the Soviets, but when war did not materialize, the issue largely disappeared in government. Simonds and Crerar could complain bitterly in public about this inattention, as they saw it, to the true needs of the army, but they were unable to move the government or the public. Peacetime conscription had its moment of possibility in 1951, but it was destined never to be implemented.

—

Still a non-starter

Many countries conscript their citizens for military service. But not Canada.

The United States ended its draft in 1973, but still obliges males from 18 to 25 to register with the Selective Service System and reserves the right to call them up in an emergency.

On the other hand, nations close to Russia take a different tack: Finland, for example, gives 80 per cent of its men compulsory military training. Sweden, which had abolished compulsory service in 2010, reinstated it in 2018, a direct response to the Russian threat.

Russia still conscripts males but increasing numbers of draftees are seeking and securing exemptions.

Historically neutral Switzerland makes service compulsory for 18 weeks of basic training and six 19-day training sessions over the following decade. But even the Swiss are grumbling about compulsory service and pressure is rising for its elimination.

And Canada? Conscription is expensive to operate and obliges thousands of regulars to do the training. For an army already short of funds, equipment and personnel, conscription is effectively impossible. More to the point, even with Russia and China aggressively pressing against global norms, there are no groups—and certainly no politicians—pressing for compulsory service. Conscription in Canada remains a non-starter.

Advertisement