a

By Michael O’Sullivan

My great, great uncle, John Henry Thomson, was 28 years old when he fought in the 2nd Battle of Ypres during the First World War.

He served with A Company, 13th Battalion, 3rd Infantry Brigade which was part of the 1st Canadian Division. The 13th Bn. was also known as the Royal Highlanders of Canada or Black Watch of Montreal.

The 13th was one of the first kilted infantry battalions to fight in the war. Unfortunately, John Henry Thomson did not return from battle. He was fatally wounded on April 23, 1915.

![Sergeant John Henry Thomson, photographed in England prior to embarkation for France, early 1915. [PHOTO: COURTESY TOM O’SULLIVAN]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/photoa.jpg)

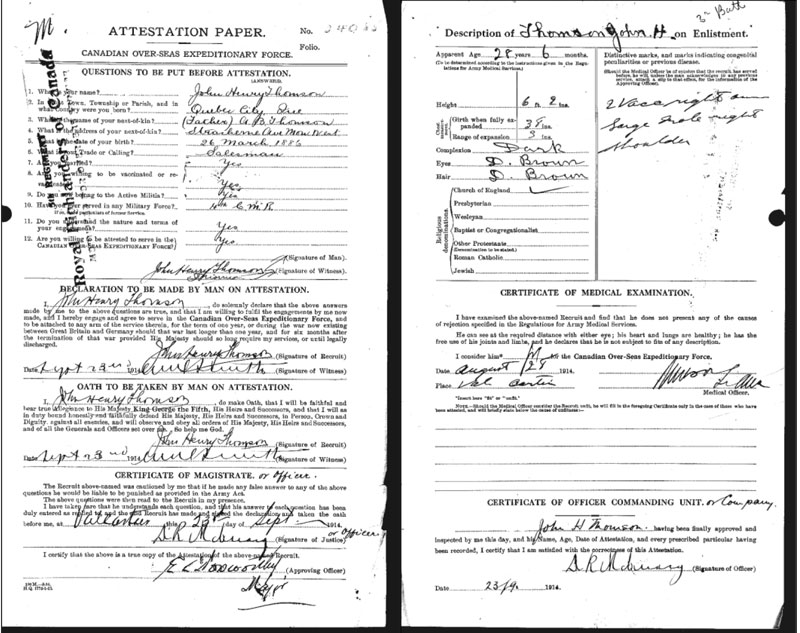

Like many of his peers, John Henry Thomson, who was born on March 26, 1886, enlisted in August 1914 soon after the outbreak of war. He was 28 years old with a height of six feet, two inches. This was an above average height.

At the time he had been employed as a salesman, and his parents lived at 128 Stratherne Ave., Montreal West.

John Henry Thomson had only been married six months—to a Miss Mary Reid of Montreal—when he left Canada with other members of the 13th. The couple did not have any children. Mary taught school in Montreal and she did not remarry after receiving the awful news of her husband’s death.

Mary’s sister Margaret married my great grandfather, Captain John J. O’Sullivan who was a Royal Engineer prior to the First World War. Capt. O’Sullivan also served in the First World War in the British Air Ministry as a Canadian engineer designing and building aerodromes and infrastructure in England and on the continent.

![The scene at Valcartier, Que., 1914. [PHOTO: LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA–C036116]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/valcartier.jpg)

After drill and training at Valcartier, Que., an advance party of the 13th Battalion left camp on Sept. 25, 1914, and the main body of the force left by train the next day. The men marched to the docks at Quebec City and soon embarked for England as part of the large armada carrying the First Canadian Contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. My great, great uncle sailed on the RMS Alaunia.

During the crossing the men drilled, played sports attended lectures and listened to concerts. When the ships arrived in England, the troops were given a warm welcome from the English people.

From there the battalion eventually moved to Salisbury Plain where it and the other units trained under constant rain, in puddles and mud and frigid temperatures. After about two months they moved out of their tents into huts that housed 40 men.

Early in 1915 the battalion received orders to proceed to France.

Ypres was an important town in Belgium. The Allies found themselves nearly surrounded by German forces to the north, east and south. This area on the Western Front east of Ypres was known as the Ypres Salient. The Western Front itself ran from the Belgium coast all the way to the Swiss border.

The Germans had been busy creating a new weapon. The idea was that a cloud of toxic chlorine gas could be blown on a gentle wind from the German front line across the enemy’s trenches, forcing the troops affected to vacate the trenches or die. Up until April 1915 the Germans had not unleashed the new weapon on enemy forces.

On April 22, 1915, they did just that.

After a night of heavy fighting and in the early dawn of April 23, 1915, Sgt. J.H. Thomson was fatally wounded by artillery fire and left behind in the trenches. At the time he had been holding the line. He died alone and in pain, amid the noise, the destruction and suffocating gas.

![The casualty report for Sgt. John Henry Thomson. []](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/illustrationc.jpg)

![The Casualty Form Active Service record for Sgt. John Henry Thomson notes his promotion and that he was reported as missing in action. []](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/illustrationd.jpg)

My great, great uncle is buried in Flanders Fields at the Poelcappelle British Cemetery near Langemark-Poelcappelle, Belgium. The cemetery is 10 kilometres north east of Ypres. It was made after the Armistice in 1918 when graves were brought in from other cemeteries in the area and from the battlefields. There are 7,478 Commonwealth servicemen buried or commemorated here, including 536 Canadians—many of them unidentified.

![The grave of Sgt. John Henry Thomson at Poelcappelle British Cemetery, Belgium. [PHOTO: TOM O’SULLIVAN]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/photoe.jpg)

![Michael O’Sullivan plays the bagpipes as a tribute to his great, great uncle who was killed in the First World War. [PHOTO: TOM O’SULLIVAN]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/photof.jpg)

![Michael O’Sullivan pays his respects at Poelcappelle British Cemetery. [PHOTO: TOM O’SULLIVAN]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/photog.jpg)

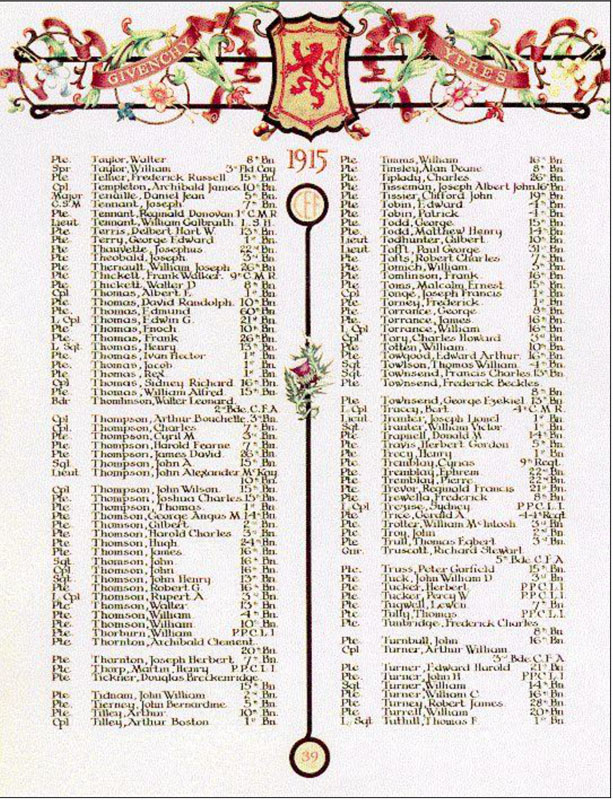

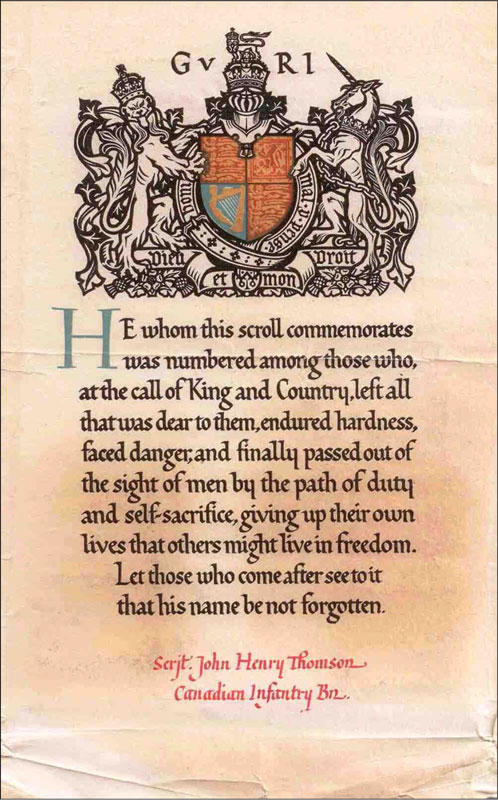

On one of my great, great uncle’s medals, the King of England wrote: “He was one of a number, who at the call of King and Country, left all that was dear to him, endured hardness, faced danger and finally passed out of sight of men by the path of duty and self sacrifice by giving up his own life so that others might live in freedom.”

The 39th page in the First World War Book of Remembrance in the Memorial Chamber of the Parliament Buildings lists Sgt. John Henry Thomson. He is one of many from the 13th Battalion who died for king and country during the war.

![Michael O’Sullivan also visited Vimy Ridge during his battlefields tour with his cadet corps. [TOM O’SULLIVAN]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/photoj.jpg)

![Michael O’Sullivan also visited Vimy Ridge during his battlefields tour with his cadet corps. [TOM O’SULLIVAN]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/photok.jpg)

Editor’s note: The story of Michael O’Sullivan’s 2013 journey to France was brought to our attention by his father, Tom, who explains that the trip was part of a European battlefield tour organized by his son’s cadet group, the Royal Canadian Army Cadet Corps, 2137 Calgary Highlanders.

The Corps is supported by The Royal Canadian Legion North Calgary Branch and represented by Capt. Jim Adams (retired) of Branch 264. “What is interesting,” explains Tom, “is that when my son was six years old he viewed some medals at home and a simple black and white wartime portrait of a highland soldier and asked who the medals belonged to and what they were all about, and who the soldier was. I told him the story of my great uncle who had served with the Black Watch. He then asked if anyone from the family had been overseas to visit the grave. I said no as it was really expensive to travel to Europe and my father, while serving in the RCAF in the European theatre of war (Second World War), was not able.

“My son, and without prompting, indicated at that time that he would one day like to go and visit the grave and play the bagpipes as a tribute to this soldier’s ultimate contribution. I was really touched. No one—at that time—played the bagpipes at home. Thus, at age 12, my son joined a cadet corps that had a highland history, and he started playing the bagpipes. He was finally able to fulfil his wish with his trip last year.

“The most important part of this is that here is a young person who was able to connect with a distant relative. The touching moment at Poelcappelle British Cemetery brought it all home with Michael. He had a quiet moment among all those who had served and never made it home. He also learned so much about his great, great uncle—a story he will continue to share.”

Perhaps you have a similar story or would just like to comment on Michael O’Sullivan’s post on our Witness To Remembrance blog. Sharing and commenting on such memories helps put a face to history. To learn more about our blog, please visit www.legionmagazine.com

Advertisement