Thomas Simpson was instrumental in the sinking of U-1302, a battle he remembers with regret to this day

My only living grandparent is Thomas Joseph Simpson, and he is my inspiration. He served in the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) during the Battle of the Atlantic, and his story, like that of thousands of others, is one of service, sacrifice and survival.

“The Battle of the Atlantic was the dominating factor all through the war,” said British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. “Never for one moment could we forget that everything happening elsewhere, on land, at sea or in the air, depended ultimately on its outcome.” The battle lasted for 5 years, 8 months and 5 days, making it the longest continuous military campaign of the Second World War. Churchill went on to say that “the only thing that really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril.”

It was the longest, largest and most complex battle in naval history, and victory came at a great price; the number of lives lost is staggering: some 72,200 Allied sailors and merchant seamen were killed. It claimed the lives of 2,024 RCN sailors and 1,629 members of the Canadian Merchant Navy. Most of these Canadians have no crosses on their graves. And for the sailors who did survive the unimaginable struggles at sea, their haunting memories, mental anguish and feelings of guilt and pain have not subsided. For them, every day is Remembrance Day.

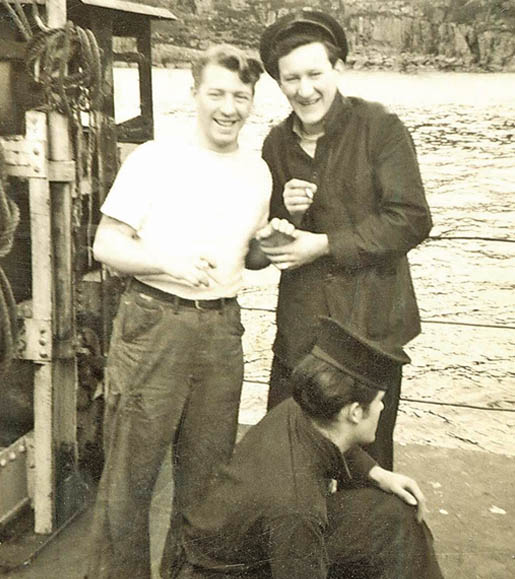

I have spent many an evening in Grandpa’s Windsor home, with him sitting in his recliner and me on the couch. We watched hockey in winter and Detroit Tigers games in summer and before too long a conversation would start up, with me asking about the war. What emerged were remarkable stories of a young sailor at sea far from home, back in the days of daily rum tots, torpedoed merchant ships, depth charge attacks, surviving on a dollar a day, fisticuffs, and an attempt to bring a captured Barbary macaque from Gibraltar to Canada, which sent the Admiralty into a fury. Grandpa’s stories are spectacular, humorous and poignant. They offer lessons about choices, responsibility and overcoming hardship. I listen in rapt fascination.

In 1942, at the age of 20, Able Seaman Tom Simpson enlisted in the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve at HMCS Hunter in Windsor, Ont. He was initially trained at HMCS Naden in Esquimalt, B.C.—and was rushed through radar training just as fast as the corvettes were built and put to sea—before further training at HMCS Cornwallis in Nova Scotia. He was then drafted to HMCS Shawinigan (K136). He also served in HMCS Toronto (K538) and HMCS La Hulloise.

Grandpa was one of the first radar operators trained in the RCN, and over time he developed enough experience at sea to command a high level of pride in his duties, confidence in his skills, and expertise with the radar set to be the radar operator of choice for the captain when entering harbour. “I was able to pick up a car on a mountain,” he says.

He sailed from Halifax to Newfoundland and New York, taking part in escort and coastal defence operations. He was in escort groups that took North Atlantic convoys from Halifax and Sydney, N.S., to Londonderry, Northern Ireland, and Liverpool, England, and through the Denmark Strait between Greenland and Iceland to the Arctic Circle, where convoys were handed off to the Russian Navy. He was also in convoy escorts transiting from the United Kingdom to Gibraltar and the Mediterranean, carrying British and Canadian troops to military operations in the Italian Campaign. During the British Isles Inshore Campaign of 1944-45, Grandpa was right in the thick of the U-boat hunt. But the unseen submarines were not his greatest fear.

“I was never afraid of the enemy, but I was always terrified of the sea,” he says. “When you get 60-foot waves coming over the bow and taking the windows out of the wheelhouse, it’s time to get concerned.” Along with thousands of other sailors, Grandpa braved the bleak, angry waters of the North Atlantic to maintain a lifeline in defence of liberty. However, service to King and country came with a great price.

“At times, I wish I was dead, too,” he says. These are difficult words for a grandson to hear as his grandfather describes his thoughts on the sinking of the ill-fated Shawinigan.

Grandpa was on two months of sick leave at the naval hospital—recovering from an injured sternum after tripping and falling chest-first onto a naval gun shell—when Shawinigan and the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Sassafras were assigned to escort the ferry Burgeo from Sydney to Channel-Port aux Basques, Newfoundland. Shawinigan was sunk by U-1228 in Cabot Strait on Nov. 24, 1944, one of only three RCN ships lost with all hands; 91 died. “Why me?” he asks. “Why did I survive when so many died?”

These questions have no answers.

“I’m no hero,” says Grandpa.

“All the real heroes

call the ocean their grave.”

Grandpa’s role, and his burden, more than 70 years later, has been to see that those who did not return are remembered as true heroes. Only he can share that story for future generations to learn. Books and films are great educational tools, but they are no match for the emotional stories of those who stared death in the face and also delivered it to the door of unfortunate foes. Grandpa, along with other veterans, visited public schools in his hometown of Windsor to talk to students about his wartime experiences.

“I’m no hero,” he says. “All the real heroes call the ocean their grave.” His medals do not make him a hero, he says. They just prove that he was there. Medals and recognition do not make any veteran a hero. The immeasurable sacrifice in blood, pain, tears, fears, cries and lost youth are much more significant. Placing a wreath on Remembrance Day and Battle of the Atlantic anniversaries bring Simpson no pleasure. “I never look forward to Remembrance Day,” he says. “When I’m on parade or at the cenotaph placing a wreath, it all comes back. And I feel bad.”

The sinking of Shawinigan was not the first time Grandpa escaped the clutches of the Grim Reaper. He and the crew somehow survived when, during exercises, depth charges were set too shallow and detonated, causing extensive damage to Shawinigan’s stern and requiring a second refit. During North Atlantic convoy runs, he witnessed merchant ships burning at sea after being torpedoed. These could easily have been his ship, he says. The convoy never stopped when a ship was hit. If it stopped, more ships and sailors would be at risk of being torpedoed and sunk.

When Grandpa served on La Hulloise, which along with HMCS Strathadam and HMCS Thetford Mines made up Escort Group 25 during the British Isles Inshore Campaign of 1944-45, his work required nearly constant alertness for days on end, because at any moment a German torpedo could, and often did, come racing silently from the depths.

In mid-February 1945, convoy SC-167 departed Halifax for England with 31 ships. Lurking in St. George’s Channel between Ireland and the U.K. was U-1302, armed with 14 torpedoes. The U-boat struck first by sinking the British cargo ship MV Norfolk Coast off Strumble Head on Feb. 28. On March 2, she sank the Norwegian vessel SS Novasli and the British ship MV King Edgar. U-1302 had sunk three ships in three days, and she was not done yet.

As attacks increased in the southern Irish Sea, and particularly in the narrow St. George’s Channel, heightened Allied patrols swept for German submarines. Several were thought to be in the vicinity, with their sights set on the numerous ships that passed through the channel to bring supplies to England and troops to Italy.

U-1302 waited to draw more blood. She had not reported her three victories, and she remained unknown to the Allies. Another German submarine, U-775, was reported in the area, however, and had torpedoed the British merchant ship SS Empire Geraint on March 6. The damaged ship sent an emergency message and EG-25 was dispatched with specific orders to hunt for U-775.

EG-25 took up formation with Strathadam as the command vessel. La Hulloise took up the port side position with Thetford Mines to starboard. On March 7, Grandpa was on watch in the radar cabin. The weather was good and the sea was calm. At approximately 8:23 p.m., he picked up a contact 1,800 yards away in St. George’s Channel north of Fishguard. He checked, rechecked, and then made his initial contact report.

One evasive technique used by U-1302 was to get as close to the coast as possible and raise its snorkel extremely close to a buoy. Radar would indicate only a single contact and be presumed to be a navigational marker. At this time, it was unlikely that a RCN radar operator would find a submarine using a snorkel, since the RCN’s radar sets were inferior to the Royal Navy’s.

The officer of the watch acknowledged that Grandpa had picked up a radar contact, but called it “a buoy sitting out” at land’s end. There was a navigational buoy marked on the charts in the location of Grandpa’s report, so it was dismissed as a threat and La Hulloise continued northward. Grandpa was ordered to continue his radar sweep. Since most RCN encounters with U-boats were on the open waters of the western and mid-Atlantic, the dismissal can be ascribed to RCN inexperience. The radar operators on Strathadam and Thetford Mines also picked up a contact, but their report only acknowledged the contact as a buoy.

Grandpa obeyed, but again picked up the same contact, which, he says, was “two pips off the port beam.” He made a second radar report to the officer of the watch, who again dismissed his report, stating clearly that it was not possible for a U-boat to be so close to the coast. The charts clearly marked a buoy in that location. He told Grandpa he was “seeing gremlins” and to continue his sweep.

At this time, since he believed the threat was imminent, Grandpa decided to take his report directly to the bridge. Strathadam and Thetford Mines did not respond, leaving only Grandpa’s warning that a German submarine was positioned for an attack.

The captain of La Hulloise, Lieutenant-Commander John Brock, hearing the verbal confrontation from his cabin below the bridge, came up top to find out what the problem was. Grandpa told the captain of his first and second contact reports and how the officer had ignored them. By this time, the ship’s ASDIC (sonar) operator had also gained contact on the same bearing as Grandpa’s radar contact. Brock ordered the ship brought around to head in the direction of the buoy. Some 100 yards from it, the captain ordered the 20-inch searchlight to pinpoint it in the darkness. A periscope and snorkel came into view and the vessel was expelling carbon dioxide—it was confirmed to be a U-boat.

At that moment, La Hulloise fired off star shells to illuminate the night sky and the ship went to combat stations. The submarine crew realized they were being attacked and started a dive. La Hulloise and the U-boat were so close that there was slight contact between them. This sent the submarine to the bottom, where she stayed. Strathadam and Thetford Mines joined the attack and, at 9:12, Strathadam launched forward-throwing Hedgehogs (anti-submarine weapons), “producing a tremendous explosion and a blue-green flash, immediately followed by air bubbles,” according to the official Admiralty report. “The position was illuminated, and from the quarterdeck, a black hulk was seen to emerge momentarily.” More Hedgehog and depth-charge attacks were made at 9:28, 9:52, 10:06, 10:25 and 11:36.

By daylight on March 8, debris from the U-boat, including woodwork, emergency food packs, clothing and human tissue, could be seen floating on the surface of the Irish Sea. A buoy was positioned to mark the contact location, and boats were launched to recover certain items from the flotsam, including personal letters and engine room journals. La Hulloise crew later handed them over to the Royal Navy. It was determined that it was not U-775, but the unknown U-1302. All 48 hands were lost.

Grandpa has been haunted by his actions for years. “Forty-eight men,” he says. “I think of what agonies each one must have gone through as the air ran out.” On the other hand, hundreds of lives were saved that night. Returning to Liverpool, Grandpa was called before the Admiralty Board and questioned about the events and, specifically, his actions during his watch that night.

What came out of that dark, cold night was remarkable. In trying to conduct anti-submarine warfare in difficult conditions around the British coast, the RCN had inferior equipment, a lack of proper training and leadership that contested evidence. Against all odds, Grandpa’s action challenged beliefs held by RCN command and set in motion a new standard of quality at sea never before seen. His diligence on the radar set and determination not to be bullied resulted in EG-25’s significant contribution to the war.

The Royal Canadian Navy recommended Grandpa for a Mention in Dispatches, but the Royal Navy recommended more than that. George Simpson, Commodore, Western Approaches and a highly decorated submariner, described Grandpa’s role as “An outstanding piece of work. The detection of the periscope and the schnorkel was invaluable in the successful prosecution of the attack.” Admiral Max Kennedy Horton, Commander-In-Chief, Western Approaches, added, “Fully concur. But I consider he merits a decoration.”

Grandpa was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) for “courage, skill and devotion to duty,” as his citation letter of Aug. 22, 1945, states. He is one of only 114 Canadians to receive the DSM in the Second World War. Grandpa indeed displayed great bravery and resource under fire, setting an example for RCN sailors to follow. He also holds the Italy Star, the France and Germany Star, the Atlantic Star bar, the 1939-1945 Star, the 1939-1945 War Medal, the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal with CVSM Clasp, the General Service Badge and the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal. The DSM is among the rarest of all orders and decorations in Canadian history.

Grandpa turns 94 on Nov. 6, and he still lives in his Windsor home, cared for by his youngest son, my Uncle Tommy. We still talk about his experiences in the navy and the discoveries from my research. His views haven’t changed much, but he accepts that it is in the past while still remembering those who never returned home.

“I wasn’t the only one,” he says. I tell him that his survival honours his shipmates, friends and others who were lost and that his stories allow us to learn about a difficult yet proud time in Canada’s history. “We did what we had to do,” he says, “and we hoped it was the right thing.”

Advertisement