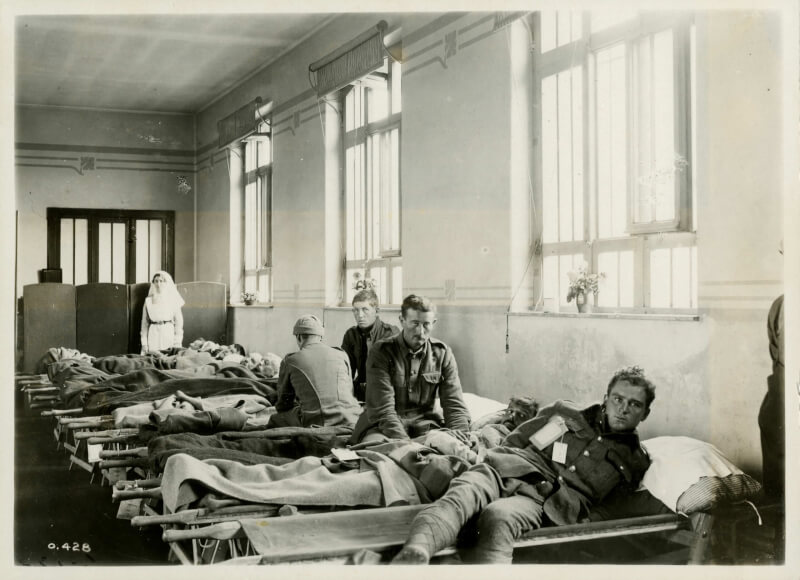

Soldiers and a nurse at No. 1 Canadian Casualty Clearing Station somewhere on the Western Front. The uniform and medical tags on the soldier in the foreground identify him as a new arrival.

[CWM/19920044-385]

Judging by the traffic descending on the medical unit closest to the Canadians’ front lines, at Auberchicourt near the Belgian border in northern France, the end of the war to end all wars was a ragged affair, fraught with uncertainty and new obstacles.

“News of ultimatum and possible cessation of hostilities received,” wrote Lieutenant-Colonel A.E.I. Bennett, officer commanding. “Hospital very busy. No particular jubilation.”

It was Nov. 9, 1918. The Hundred Days’ Campaign spearheaded by Canadian shock troops was drawing to a close, though you’d never know it by the sick and wounded filtering into the station where casualties would be stabilized before they were returned to their units or transported to hospitals.

Formed in Liverpool, N.S., and Valcartier, Que., No. 1 had been acting in the latter stages of the war as an advanced operating centre behind the Canadian Corps.

The bulk of its work had been “heavy surgical.” By now, however, it had become a full-blown medical station “with a considerable number of influenza and bronchial pneumonia cases.”

Some 40 million people would die during the Great War; it’s estimated the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 killed at least another 25 million, though some researchers project the toll may have been twice that many.

No. 1 CCCS—11 officers and 75 other ranks—had sailed with the first contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force in October 1914. It deployed to France in February 1915 and virtually didn’t stop until three months after the war ended.

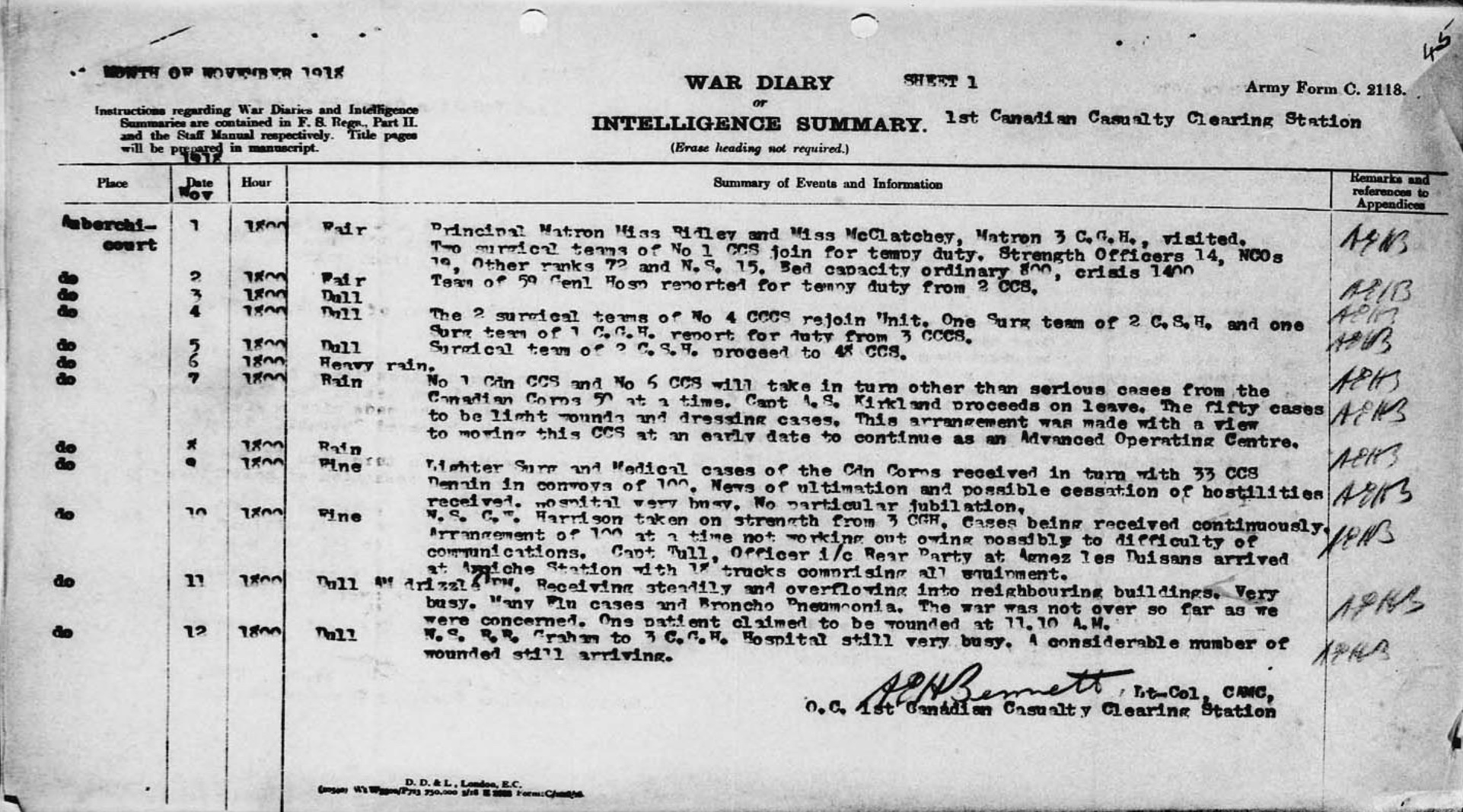

The early-November 1918 war diary of 1st Canadian Casualty Clearing Station describes busy days surrounding the war’s end.

[LAC]

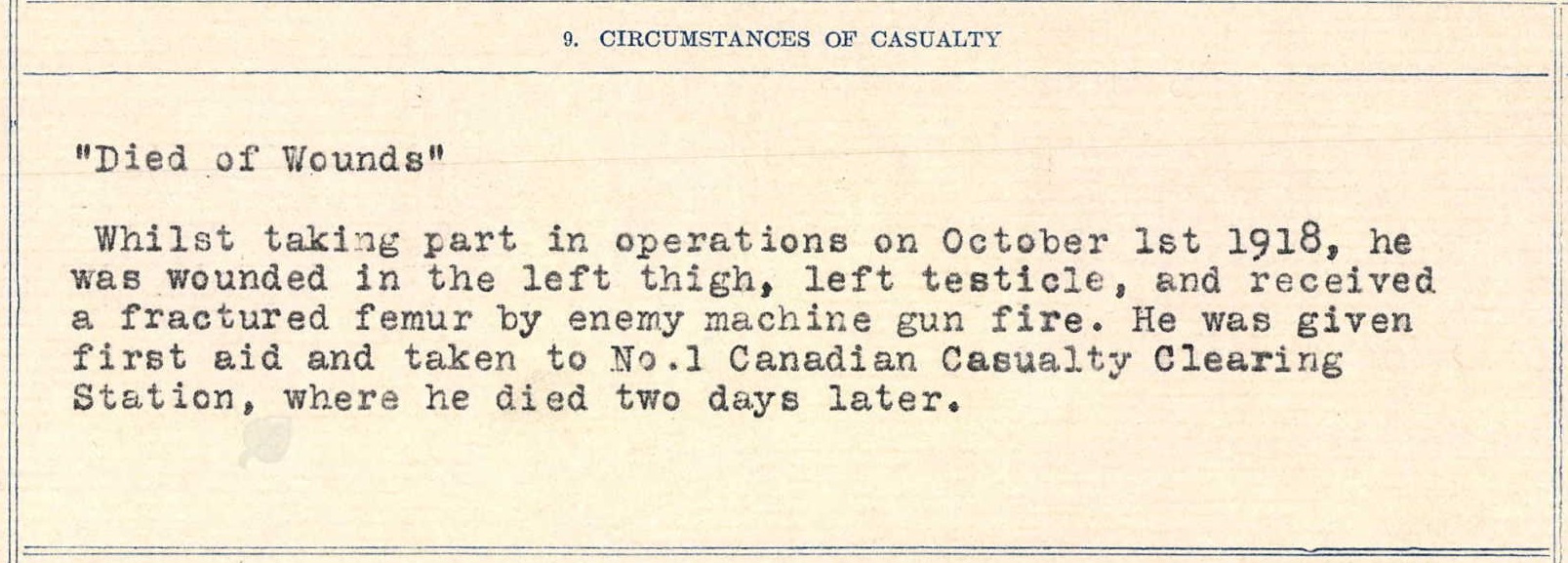

Throughout the war, No. 1’s capacity ranged from 200-900 beds, though it averaged more than 1,000 admissions a month—and around 20 deaths—for the entire time it was a first-line unit.

At the outset of the Battle of the Somme in July 1916, 1st Canadian Casualty Clearing Station, located at Bailleul in northern France at the time, took in 2,810 wounded and lost just 70, a 97.5 per cent survival rate.

As the fighting intensified, so too did the casualties. From December 1916-February 1917, the unit admitted 3,564 wounded. Deaths don’t appear to be recorded in the war diary at this point.

After moving to Aubigny-sur-Nère, south of Paris, in March, No. 1 took in 4,273 casualties in April (the month Canadians fought the April 9-12 Battle of Vimy Ridge), including 1,039 on the 10th. Another 3,461 came in during May 1917.

No. 1’s capacity ranged from 200-900 beds, though it averaged more than 1,000 admissions a month—and around 20 deaths—for the time it was a first-line unit.

Nov. 11, 1918, dawned a dull, drizzly day. The patients came in a steady stream, overflowing into nearby buildings. The fighting officially ended at 11 a.m., but Bennett wrote that “the war was not over so far as we were concerned.”

“One patient claimed to be wounded at 11:10 a.m.”

The sick and wounded—Canadian, British, French—continued arriving at 1 CCCS and other medical units for days, including “some wounded and gassed civilians.”

In an entry on Nov. 14-15, Bennett reports that a “Sgt Spooner” had been slightly wounded at the same time as his father, “also a sergeant.” The father had gone to the dressing station and received a tetanus shot; the son did not and now had tetanus.

Caused by a toxin-producing bacterium, tetanus, or lockjaw, affects the nervous system. It’s marked by muscle contractions, particularly in the jaw and neck. And it can be fatal.

The young sergeant was actually a corporal, Lancelot Gange Spooner, formerly a bank clerk from Vancouver who had just marked his 20th birthday in September. He had sustained shrapnel wounds to his left leg.

His father was Francis Woodbury Spooner, not a sergeant either, but a 45-year-old lieutenant, also wounded in the left leg. Both were in the 72nd Battalion (British Columbia Regiment).

The station was out of anti-tetanus serum.

“The bulk of our supply has been called in,” Bennett wrote. “We used what we had and applied to every Adv Depot Medical Stores and CCS within reach. None had it.”

Staff eventually found out No. 1 CCS (British) in Mons had obtained the last of the stores of serum. It took some effort during the night to reach the 12th Brigade about 27 kilometres away, near Valenciennes, with a request to send a dispatch rider (‘D.R.’ in the diary) to find the British unit and retrieve some.

The brigade major happened to know both father and son and immediately sent one of his men, probably riding a 1914 Triumph 550cc ‘H’ type motorcycle.

“Serum was retrieved about 8 a.m. 15th after a very long and adventurous ride by the D.R. Also he had been held for three hours under arrest in Mons through some misunderstanding. Serum arrived before dose was due but unfortunately was of no avail.”

Lancelot Spooner died. He was buried in the Auberchicourt British Cemetery, Plot 1 A 16, Stone No. 34. His father Francis lived to the ripe old age of 93 and died April 9, 1967.

“The convent made an excellent hospital—good kitchens, baths, laundry and numerous large rooms.”

While Spooner was taking his last breaths, four unit nurses were on their way to Mons, Belgium, on orders to accompany Canadian troops as they made their official entry—what amounted to a victory parade—into the city where the Canadian Corps fought its final battle of the war.

It was near Mons where Private George Lawrence Price of Falmouth, N.S., is said to have been the last British Empire soldier killed in WW I action—at 10:58 a.m. on the 11th, two minutes before the armistice took effect.

No. 1 CCCS was still busy with its last patients at Auberchicourt on the 18th, most of them flu cases. The team evacuated 63 and began packing and “adjusting equipment to new requirements, i.e., for three hundred patients with only 50 beds for serious cases.”

Three days later, an advance party was dispatched at sunrise to locate the unit’s next site some 100 kilometres away at Gosselies, Belgium.

Twenty-five lorries arrived at noon and loading began.

Two nursing sisters, Harrison and Tate, had taken seriously ill and had to be left behind when the last of the unit pulled out on the 23rd.

“Every provision was made for them—good quarters, plenty of rations and two orderlies and sisters especially detailed to care for them,” wrote the OC. “Both were admitted as patients in 23 CCS.”

Soldiers of the 5th Battalion (Western Cavalry) carry a wounded soldier to a light railway behind the lines.

[ CWM/19920044-509]

“Made tea in French farm house and had lunch on road side,” he wrote. “Passed large number of refugees with all varieties of conveyances from a horse and a cow hitched up together to a push cart pulled by a man and a dog and pushed by several women. All appeared very glad though tired.

“Gay decorations everywhere and innumerable troops and transport.”

They weren’t in Gosselies 12 hours when they admitted their first patients after settling on their new location, the Convent de la Providence, a large building used by the Germans on their advance in 1914 and again on their retreat in 1918.

“The good nuns had thoroughly cleaned the place and stacked the German beds and mattresses. These were soon placed so that within a few hours after arrival on the 23rd we were ready to receive.

“The convent made an excellent hospital—good kitchens, baths, laundry and numerous large rooms.”

Large numbers of returning prisoners of war were arriving “in shocking condition, starved, emaciated, very scantily clad and dirty.”

The unit was now at the fore of the casualty clearing stations on the road to Germany. Bennett said large numbers of returning prisoners of war were arriving “in shocking condition, starved, emaciated, very scantily clad, very lousy [infested with lice] and dirty with wounds and sores showing gross lack of care or treatment.”

By their fourth day in Gosselies, No. 1 already had more than double the number of patients their 300 beds accommodated, but the OC said they had expected this and were managing. About half the returning PoWs were French.

In the month of November 1918, 1st Canadian Casualty Clearing Station admitted 660 Canadians, 38 of whom died, a 94 per cent survival rate. It also admitted 408 other British Empire troops (15 died), 34 civilians (10 died) and 176 others (four died) for a total of 1,416 admissions and 67 deaths—a 95.3 per cent survival rate.

The nursing sister Harrison, who had just arrived with the unit when she was taken ill, had died. Tate apparently survived. The records list only nurses who died as a result of enemy action.

By Dec. 5, No. 1 was preparing to move again. Patients were evacuated to hospitals and other casualty clearing stations.

Canadian medical officers and German PoWs transport Canadian wounded from Vimy Ridge in April 1917 using a two-tiered carrier, pulled along a light railway line leading from the front.

[CWM/19920085-924]

The road out of Belgium was filled with “rejoicing,” including “innumerable triumphal arches over road and flags of Allies everywhere with odd German effigy hung and stabbed by the roadside.”

They were held up three hours in Stavelot, Belgium, about 100 kilometres from their new destination, waiting for gasoline to arrive at a newly established railhead. “A few German officers and soldiers about.”

The Canadians crossed the border at Eupen, Belgium—“no flags no decorations.” They were “misdirected” along the way and lost two hours. “At Duren, an English-speaking German girl gave minute directions and Euskirchen was finally reached without too much trouble.”

“All ranks very busy preparing to give Canadian Patients the best possible for their first and last Christmas dinner on the Rhine.”

The station set up in an institute for the deaf and mute, which Bennett said “lends itself for hospital purposes the best of any building hitherto occupied—a modern building with large class rooms, centrally heated, electric light throughout, excellent sanitary arrangements, a large kitchen and excellent dining room, plenty of baths and in addition an up to date series of shower baths in the basement….”

There were disinfecting and disinfesting chambers, too, and ample storage. “One could not help thinking it had been built with a double object,” Bennett observed.

They were set up within hours of their arrival. It was the night of Dec. 10-11. The sick and wounded started arriving around midnight. By the 13th, the unit had 367 patients—and orders to move to Bonn.

Bennett and a major visited the city on the 14th to select a site, but found none suitable on Day 1. They decided on St. Marien’s Hospital the following day, but when they informed local authorities via interpreter, they “encountered strenuous opposition.”

“They call in German Director of Medical Arrangements and a German Professor who is interested in this Hospital,” Bennet reports. “German board admit Canadian patients entitled to best in town but offer every objection and misrepresentation of facts possible.

“Finally they admit that no interest of town or German patients now in this hospital will suffer and matter is apparently settled. Apparently the reason for obstruction was that certain private interests would suffer.”

Soldiers deliver wounded to a reception tent at a Canadian casualty clearing station.

[CWM/19920044-811]

Bennett dispatched two officers and a small party to monitor their withdrawal and ensure that specified furniture and equipment stayed. “We found them taking things away that were supposed to be left.”

No. 1 was taking patients at Bonn by Dec. 21. Their first death was the following day, a dispatch rider who had collided with a lorry. He was buried in a local cemetery.

On the 22nd, Bennett wrote: “All ranks very busy preparing to give Canadian Patients the best possible for their first and last Christmas dinner on the Rhine.”

Over the course of the war and beyond, 1st Canadian Casualty Clearing Station recorded 42,489 admissions and 794 deaths, a 98 per cent survival rate.

On Christmas Day 1918, General Arthur Currie, commander of the Canadian Corps, and an entourage visited the unit and made the rounds, wishing patients a Merry Christmas before the sick and wounded had dinner at 11:30 a.m.

“It was most bountiful thanks to the Cdn Red Cross and other friends in Canada as well as the efforts of the staff and personnel,” Bennett wrote. “The up patients sat at long tables down the centre of the largest ward with a row of bed patients on each side.

“The decorations, the Christmas tree and the large Red Cross Christmas stockings made a festive show. All were delighted.”

Personnel and others sat down at 4 p.m. around a table in the recreation room, calling it “one of the best” Christmases of their deployment. At 8 p.m., officers and nursing sisters sat for a combined Christmas dinner, speeches and laughter.

“It is safe to say that this day will be remembered.”

On the 28th, Bennett recorded 94 patient departures and 59 remaining, and said “the large numbers of invitations for Nursing Sisters and officers to attend social gatherings among the Canadians threatens to become overwhelming.”

Canadians wounded at the Battle of Amiens lie outside of the 10th Field Ambulance Dressing Station, a waypoint near the front en route to a casualty clearing station and, ultimately for most, hospital. German PoWs who likely helped transport them are also present.

[ CWM/19930012-404]

The moves contributed to what turned out to be a busy month.

“It found us at Gosselies and left us snugly seated in the best hospital in Bonn on the Venusberg overlooking the City and the Rhine,” wrote the OC. “We had accomplished two long moves and reached the goal dimly contemplated in 1914—one Christmas in England, three in France and this last one in Germany.”

Bennett would be posted to London as the unit wrapped up operations at the end of February. Over the course of the war and beyond, 1st Canadian Casualty Clearing Station recorded 42,489 admissions and 794 deaths, a 98 per cent survival rate.

The first of its doctors, nurses and orderlies departed England aboard SS Coronia about 9 p.m. on March 29, 1919. They docked in Halifax on April 5.

Their war was over.

Advertisement