War artist Richard Jack’s portrayal of Canadians fighting during the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915. The piece, measuring 371.5×589 centimetres, was the first of almost 1,000 works by more than 100 artists commissioned by Lord Beaverbrook’s Canadian War Memorials Fund.

[Richard Jack/CWM/19710261-0161]

He was among the 70 per cent British-born war volunteers in the first contingent of Canadians—from Wales, to be exact. He had served six years in the 41st Infantry Regiment, based in Cardiff, Wales, before emigrating to Canada, though it appears he may have been living south of the border in Virginia and came north when the First World War broke out.

At 37, he was a relatively young widower, and a relatively old soldier. He stood five-foot, three-and-a-quarter inches when he was assigned to the 1st Battalion (Ontario Regiment).

The unit headed overseas with the first convoy departing the Gaspé coast on Oct. 3, 1914—32 transport ships carrying 33,000 troops and 7,000 horses. The 45 officers and 1,121 enlisted ranks of the 1st Battalion arrived with the others at Plymouth Hoe, England, 11 days later.

Private Davis’s war didn’t last long—just seven paycheques, was all.

After training on Salisbury Plain, the 1st had shipped off to France, where it trained some more before it joined the fighting outside of Ypres, in western Belgium, 15 kilometres from the French border, in the spring of 1915. A 24-square-kilometre salient had formed around the medieval trade centre and the 4.4 million Allied troops that stood between the 5.4-million-strong German army and the sea.

The dark line on this map published by the New York Times in 1915 shows the Ypres Salient as it appeared more or less at the start of the Second Battle of Ypres, and the shaded territory shows the major area of fighting. The first gas attacks were launched in the area between Steenstraate and Langemarck, garrisoned by the French 87th (Territorial) and 45th (Algerian) Divisions. The Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry in 1915 part of the British Army, had their baptism of fire southeast of Saint-Julien at Frezenberg, as part of the 28th Division. When all was said and done, 2nd Ypres cost the Allies 70,000 men, and the Germans 35,000—but was considered an Allied victory. The Germans never broke through the Allied lines at Ypres. [New York Times]

Details of Davis’s death are sketchy. His service record confirms he was killed in action between April 22 and 23, 1915. Under place of death, it states “In the Field.”

The Passchendaele Museum has launched a program called Names in the Landscape that locates the places where unknown soldiers died. It reported Davis met his end near Foch Farm in Pilkem, just north of Ypres (now known by the Flemish Ieper, pronounced ‘EE-per’) and east of the Canadian positions between Saint-Julien and Gravenstafel where the second gas attack took place the day after he is believed to have died.

A June 2, 1915, report by a Major Beattie says he was “buried east side of Ypres to Pilkem road near shrine about 400 yards from where Pontoon Bridge crosses over road. Share grave with 16 others who fell at the same time.”

It was the last trace of Edwin John Davis recorded in more than a century.

A reconstructed German trench on the grounds of the Passchendaele Museum in Flanders.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Iarocci challenged those who blamed the high Canadian casualty rate and loss of ground at the Second Battle of Ypres on training.

During the night of April 22-23, the 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade marched out of its reserve billets shortly after 3:15 a.m. to help deal with the emerging crisis at the front. Davis’s 1st Battalion, along with the 4th (Central Ontario), were to launch a counterattack around dawn against German positions along the east-west line of the Mauser Ridge.

“The attack, designed to stabilize the front, lasted for most of the daylight hours of 23 April,” Andrew Iarocci, a historian at London’s University of Western Ontario, wrote in his 2003 paper 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade in the Second Battle of Ypres: The Cases of 1st and 4th Infantry Battalions, 23 April 1915.

“Upon first examination it seems to conform to the stereotype of ‘unprepared’ Canadians being thrown haphazardly into hopeless battle that is so often associated with the earlier war years.”

But Iarocci challenged those who blamed the high Canadian casualty rate and loss of ground at the Second Battle of Ypres on training that had been undermined by poor weather, excessive leave, rampant sickness and a shortage of instructors.

The attack on Mauser Ridge was typical of so many futile actions of the time—a suicidal charge across 1,400 metres of largely open ground, with a single line of hedges and willow trees bisecting the area about halfway between the Canadian and German positions.

Simon Augustyn, a historian and research officer with the Passchendaele Museum, described the gentle slope between Kitchener’s Wood and the Yser Canal as “the ideal springboard for renewed German attacks.”

At first, their progress was good—the Canadians’ right flank had covered half the distance to their objective in 20 minutes. “All goes well so far,” reported the 1st Battalion commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Frederic William Hill, a lawyer and the former mayor of Niagara Falls, Ont.

But the Germans were holding their fire until the Canadians were within 500 metres. Indeed, soon after Hill’s message was received, all hell broke loose on Mauser Ridge.

“Without preparatory artillery shelling, at dawn, the Canadians made an easy target,” wrote Augustyn. “The well-entrenched Germans rained bullets on the advancing units. There was virtually no cover to be found.”

The view from a reconstructed German trench at the Passchendaele Museum in Flanders, looking through a peep-hole

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Hill reported that only 100 men from his company were available as reserves.

The French had failed to advance on the Canadians’ left as planned. The Canadians were asked to fill the vacuum, but they were taking casualties and under heavy fire halfway up the slope.

At 10:50 a.m., the 4th Battalion’s Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Percival Dearman Birchall, a native of Gloucester, England, seconded to the CEF, sent a dispatch informing command that the “whole line is now digging in.”

“Line extends from YPRES-PILKEM Road to I think about 600 yds. East of road. Casualties are heavy,” he wrote. “MIDDLESEX [regiment] are on our right and I do not know exactly how far they extend.

“We reached a point about 450x from German Trenches As all my companies are up in line and I cannot well move them to a flank in daylight I cannot extend our road [line] towards Canal unless absolutely necessary.”

Captain Malcolm Alexander Colquhoun of Brantford, Ont., officer commanding ‘B’ Company, 4th Battalion, was already down to half his men by the time they were ordered to dig in.

Hill reported that only 100 men from his company were available as reserves—far too few to fill the gap. The open flank was reported closed just after 11 a.m., however, when brigade informed the Canadian battalions that the French “now have five battalions between you and the canal.”

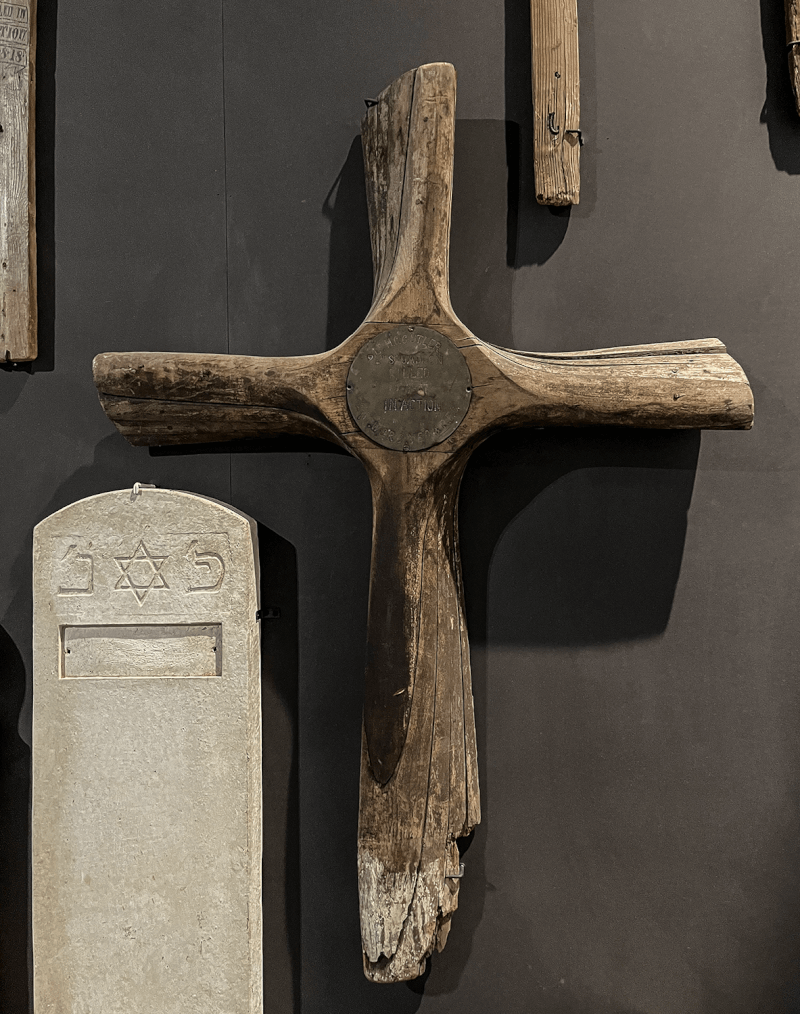

The battlefield grave marker of an American pilot killed in the Ypres Salient in 1917, on display during a special exhibition at the In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

The 1st and 4th were under fire the entire day. The Canadians resumed their attack in the afternoon, advancing less than 200 metres before they were halted, and Birchall was killed, under withering fire. “He went up the field just as if there was not a war on,” Frank Betts wrote in a letter home, “and the bullets, shrapnel, Johnsons [large German shells] and war shells were as thick as hail.”

Reported The London Times: “It is safe to say that the youngest private in the rank, as he set his teeth for the advance, knew the task in front of him, and the youngest subaltern knew that all rested upon its success. It did not seem that any human being could live in the shower of shot and shell which began to play upon the advancing troops.”

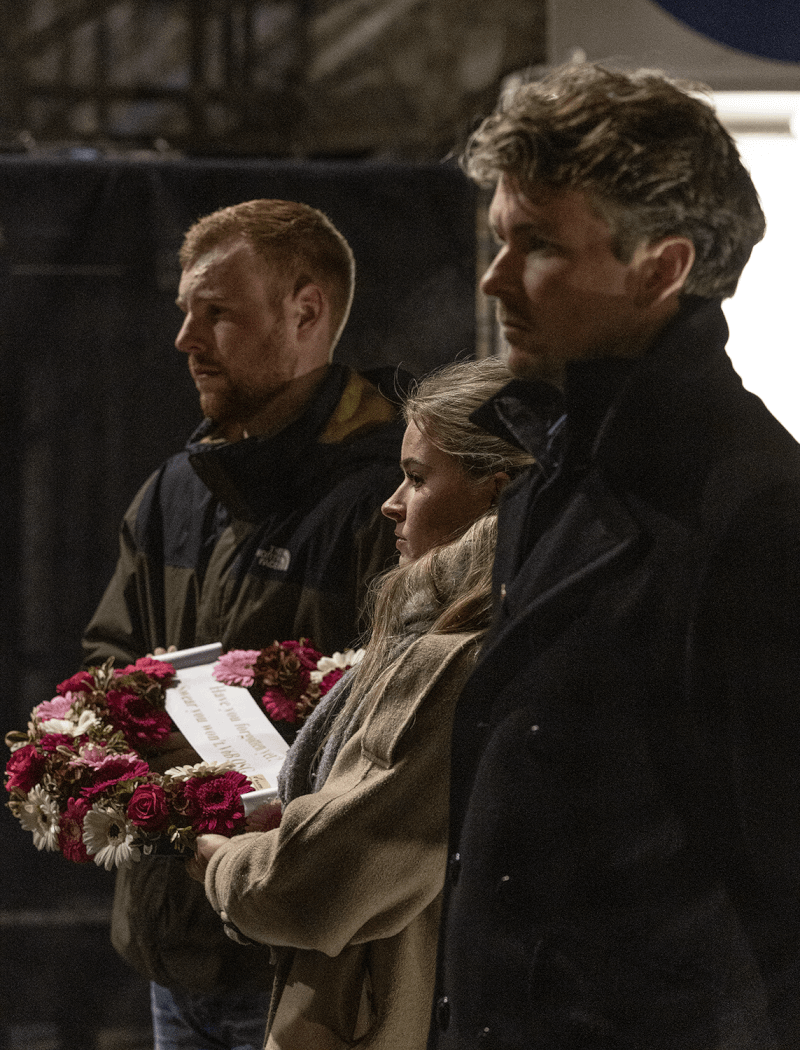

Guests await their turn to place a wreath during the nightly ceremony at the Menin Gate in Ypres. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Hill reported that only 100 men from his company were available as reserves.

Private A.W. Wakeling of 4th Battalion, described how his ‘B’ Company was told to take a German trench at 5 a.m.

“We had been lying down behind a hedge, and we no sooner showed ourselves than a terrible fire was opened up, machine gun, rifle and shrapnel,” he wrote. “It came from all directions on our front and both flanks; our boys went over in dozens.

“It took us just one hour to take the trench the French had lost. Only 250 of us were left and five officers. We lost about 700 men and 20 officers that morning…. In my platoon, 55 started and only 11 of us reached the trench.”

Iarocci says Wakeling overestimated the 4th Battalion casualties: the records show 18 officers and 487 other ranks killed, wounded or listed as missing.

Regardless, “the worst was yet to come during the day,” wrote Wakeling. “We had no artillery behind us and we had to hold the trench at all costs.

“The artillery started shelling us right away to drive us out…. Towards evening our artillery came into action and reinforcements from the British Army.”

Augustyn said no headway was made but the counterattack did prevent the German advance from Mauser Ridge to the south.

Davis’s 1st Battalion was relieved on the 24th.

Temporary battlefield graves were often obliterated in the repeated fighting and territory often changed hands over the course of the war. Remains were lost or pummeled beyond recognition in the relentless artillery strikes and mud before recovery teams could return and relocate them to formal, centralized cemeteries.

Augustyn’s museum team identified the graves of 11 Canadians buried at the site, along with the wartime grave of Birchall, one of the senior Canadian officers listed on the Menin Gate.

The memorial’s stone panels bear the names of 54,395 British and Empire soldiers killed in the salient whose remains were never identified or found, including 6,928 Canadians.

The memorial proved too small to contain all the names of those whose remains were never identified or found, so the names of 34,984 British declared missing after the arbitrary date of Aug. 15, 1917, were inscribed on the Tyne Cot Memorial instead. The Menin Gate also does not list the names of the missing from New Zealand and Newfoundland. They are honoured on separate memorials.

Buglers play during the nightly ceremony at the Menin Gate in Ypres. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

“The former criticism has been levelled against British and French commanders many times during the last 80 years, but once again, the reader is challenged to come up with an alternative course of action under the circumstances.”

With most of Belgium already occupied, Iarocci notes, Ypres had become symbolically important to the Allies, particularly since the British Expeditionary Force had made its stand there in the autumn of 1914. The town was a strategic gateway to the channel ports that needed to be defended so the British could protect supply routes.

“Allied leaders elected to stand their ground and senior commanders were compelled to function within these parameters,” writes Iarocci. “As the German attack gained ground under a cloud of chlorine gas, hints of panic appeared in the Allied ranks.

“It was deemed necessary to counterattack, throw the enemy off balance, and gain time to reinforce. Senior officers did their best to re-shape plans in this fluid situation. Thus, there was no demand from above that Birchall carry through the initial assault at all costs once it had gone to ground before reaching its objective.

“When Canadian Divisional headquarters learned of the high losses that Birchall’s force was suffering, it ordered 1st Brigade to dig in and await further reinforcement. After receiving these orders from brigade, Birchall and Hill acted accordingly.”

German forces would never come closer to Ypres than they did in April 1915.

—

This is the latest in a series on the war in Flanders. Next, on Jan. 10, the myth of Langemarck, and how German propagandists turned defeat into a propaganda victory.

Advertisement