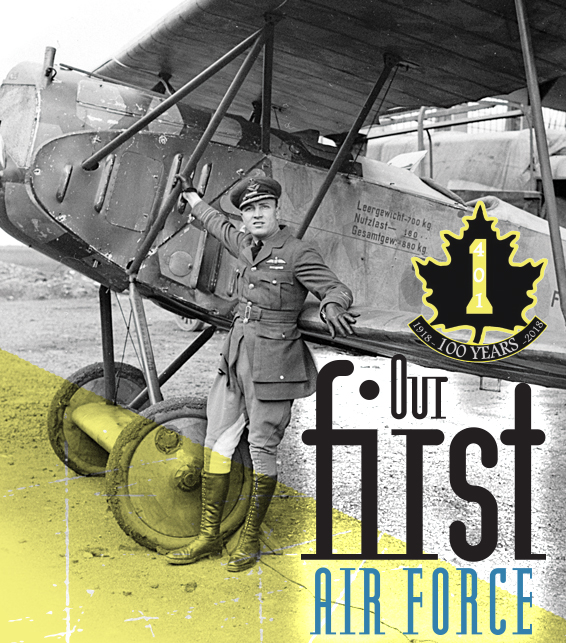

Major Andrew McKeever, the first commanding officer of No. 1 Squadron, leans against a captured Fokker D.VII aircraft in Upper Heyford, England. [DND/LAC/PA-006011]

Formed, disbanded and resurrected, 401 Squadron has been at the heart of Canada’s air defences for a century.

Much of the history of the Royal Canadian Air Force’s 401 Squadron can be seen in a quick glance around Klersy’s, the unit’s lounge in its hangar at 4 Wing Cold Lake in Alberta. There are photos and newspaper clippings, but what really stands out is a timeline for the unit during the Second World War. Under each year of the war is a column of aircraft silhouettes, representing each enemy plane destroyed or disabled by the squadron. A “kill” is a full silhouette of the aircraft type. Half an aircraft is shown when it was ruled as a probable kill or damaged.

“We were the top-scoring unit in the 2nd Tactical Air Force,” said Master Corporal James Ferris, who administers the unit’s Facebook page. The squadron boasted 112 aerial victories between June 6, 1944, and May 5, 1945. Its total confirmed score for the war was 186.5.

All that history is being celebrated this year as 401 Squadron celebrates 100 years since it was formed overseas in 1918 as No. 1 Squadron, Canadian Air Force.

The squadron cannot claim 100 years of continuous service, having been disbanded and reactivated several times. Instead, it has existed like a phoenix, rising from its ashes time after time to add to its already impressive list of honours.

A commemorative painting by aviation artist Mark Stevens shows some of the aircraft the squadron has flown, including (from left) the Spitfire, the Sopwith Dolphin and the CF-18 Hornet. [Mark Stevens]

“Our mission is exactly the same as that of 409 Squadron, which is the delivery of air power in defence of North America or anywhere we are asked to deploy,” said Lieutenant-Colonel Forrest Rock, the commanding officer.

Rather than expand 409 Squadron at 4 Wing, it was decided that a new squadron should be created. “The number 401 was selected. I think there is a desire to go back to our roots,” said Rock. “It seems to fit in with restoring the Royal Canadian Air Force title and changes to our insignia.”

Restored with the insignia is the nickname, the Rams. A trophy head of a Rocky Mountain sheep was donated to Klersy’s by the Alberta Hunter Education Instructors Association.

“We’ve always had the nickname Rams. All squadrons have a name,” said Rock. “But we have been noted for ferociousness.” Indeed, the squadron’s motto is Mors celerrima hostibus, meaning “very swift death for the enemy.”

The squadron has approximately 165 personnel with 18 pilots and 13 jets. “We are a mix of regular force and reservists,” said Rock. “We work well together. You can’t tell the difference between regular and reserve. We are always training. Sometimes a horn goes off and we have to scramble.”

It’s a challenge that has been heightened in recent years with increasingly aggressive moves by Russia, Norad’s longtime Cold War opponent. “We are ready to respond to any bad actors, no matter where they originate,” said Rock.

While the unit goes about its day-to-day vigilance, a number of activities have been held or are planned to mark the centennial.

An anniversary patch has been designed and painted on the tail of the fighter aircraft. Special permission was sought and granted to give each jet in the squadron a unit number beginning with “YO,” the call letters used by the unit in the Second World War.

Aviation artist Mark Stevens was commissioned to create a commemorative painting showing some of the aircraft the squadron has flown over the past century. Limited-edition prints were ordered, each signed by the artist.

Stevens is the father of Captain Scott “Flanders” Stevens, a United States Marine Corps exchange officer who recently served with the squadron. “A lot of people in the squadron have some sort of family connection,” said Rock. “Another captain, Paul Shaver, is the great-nephew of Andrew McKeever, our first commanding officer.”

A special exhibit was prepared for the Cold Lake Air Show. Arrangements were made with the National Air Force Museum of Canada in Trenton, Ont., for a Spitfire and a Hurricane to be displayed at the air show.

“We are working with the City of Westmount for a Freedom of the City,” said Rock. “Each reserve unit used to be affiliated with a city. When we were stationed in Saint-Hubert, Que., we were affiliated with Westmount in Montreal. The last time we were given Freedom

of the City was in 1984. It meant we could parade through the city with our bayonets and weapons.”

Recently the squadron became an official affiliate of The Royal Canadian Legion’s St. Paul Branch, 110 kilometres southwest of the base. The branch recently gave the unit a plaque to mark the anniversary.

The squadron will also be going to Europe in the fall to take part in exercises conducted in Norway. “After that, we are hoping to do a short pilgrimage to Europe to visit some of the graves of our members in France, Belgium and Germany,” said Rock.

Pilots from 401 Squadron, RCAF, wait for their Spitfires to be refuelled between flights in support of the raid on Dieppe on Aug. 19, 1942. [DND Archives/PL-10627]

An early advocate was Major-General Richard Turner, VC, chief of the general staff in Britain and later one of the founding leaders of the Legion. His staff analyzed the RFC and RNAS. As of April 1, 1918, it found that 13,345 Canadians had served in the two services. By omitting casualties and other forms of loss, it was estimated that 10,990 Canadians remained in Britain’s air services.

The Canadians within those units felt they were being passed over by British officers and not being given the same opportunities. As Turner put it, “Canada is most generously represented in the lower ranks of the flying officers of the air force but she is most inadequately represented in the senior appointments and administrative positions. So long as this condition exists, the Canadian personnel will feel, as they do, that the Canadian authorities are lukewarm in their support and careless of their interests and the interests of Canada.”

Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie, the commander of the Canadian Corps who worked closely with air forces in support of his set-piece attacks, was also supportive of the idea. Still, authorities in Ottawa were cautious and British authorities preferred that the current structure remain in place until the war was over.

Finally, the Canadian position won out and in August 1918, orders were given to create two squadrons made up entirely of Canadian personnel. One was to be a fighter squadron with Sopwith Dolphins and the other would be a bomber squadron. Put in charge of finding the Canadians to fill the positions was Major William (Billy) Bishop.

No. 1 Squadron was led by Major Andrew McKeever, an ace credited with destroying 31 aircraft within a five-month period. He assumed command at Upper Heyford, 110 kilometres northwest of London. “We became operational on Nov. 20, 1918, nine days after the Armistice,” said Ferris.

The history of No. 1 Squadron and its sister, No. 2 Squadron, the bomber unit, was short-lived. Canadian authorities had given little thought to maintaining an air force back in Canada in peacetime. The Canadian cabinet heard many arguments for it, but in the end, the costs seemed too great and the Canadian Air Force was told to stand down. The units were disbanded in 1919, with many of the officers returning to the Royal Air Force.

“We disbanded on Jan. 29, 1919. Our planes were dismantled and shipped back to Canada,” said Ferris.

A CF-18 fighter from 401 Tactical Fighter Squadron prepares for flight during exercises at Holloman Air Force Base in Alamogordo, New Mexico, in January 2018. The image of a ram is painted on the tail. [Cpl. Manuela Berger, 4 Wing Imaging]

There would be moves to Saint-Hubert, Que., and Dartmouth, N.S., before the unit was sent overseas to RAF Middle Wallop in southern England. After further training and a transfer to Croydon Airport, the squadron was finally ready for operations.

On its second patrol on Aug. 26, 1940, during the Battle of Britain, it met with 25 to 30 Dornier bombers. In the fight that followed, the squadron is credited with three aircraft destroyed and three damaged. But it was not without losses. One Canadian pilot, Flying Officer Robert Lesley Edwards, was killed and three aircraft were lost.

The squadron transferred again to Prestwick, Scotland, to do coastal patrols over the River Clyde approaches. Over a 53-day period, it shot down 29 aircraft, probably destroyed eight and damaged 35. The most successful pilot was Flight Lieutenant Gordon McGregor with five kills, one more than Squadron Leader E.A. McNab. McGregor later succeeded McNab as the commanding officer.

To avoid confusion with the Royal Air Force, the Canadian squadrons were given numbers 400 to 449 to indicate that they were Canadian, so No. 1 Squadron became 401 Squadron.

In 1941, the Hurricanes were replaced with Spitfires. From 1942 to 1944, with the Battle of Britain won, the squadron flew mostly escort for bombing missions over Europe. It was part of the formidable air support for the Canadian troops on the Dieppe Raid on Aug. 19, 1942. The squadron had two probable kills and three damaged aircraft that day.

There is a special display on the wall at Klersy’s devoted to Flight Lieutenant Wally Floody, who worked in the mines in Timmins and Kirkland Lake in Northern Ontario before enlisting and became one of the key players in what has come to be known as “The Great Escape.”

Operating out of RAF Biggin Hill, Floody’s Spitfire was shot down on Oct. 27, 1941, over Saint-Omer, France. He was sent as a prisoner of war to Stalag Luft III at Sagan, which today is Zagan, Poland. There he oversaw the secret excavation of three tunnels, one of which was eventually an escape route for 76 prisoners (see “Abused Prisoners and Great Escapees,” May/June). Floody, however, did not make it out through the tunnel. The Germans had grown suspicious of him and transferred him to another camp before the escape.

The squadron continued to move about England, stationed at RAF Redhill, RAF Staplehurst and RAF Biggin Hill. Following the Normandy invasion in June 1944, the unit moved to an airstrip at Bény-sur-Mer, France. The squadron claimed its 100th kill on July 20 and on July 27 shot down seven Messerschmitt Bf 109s over Caen.

The squadron then moved to the Netherlands where it was stationed first at Volkel and then Heesch. On Jan. 1, 1945, the Luftwaffe launched a massive ground attack. In defence of the ground forces, the squadron shot down nine of the attackers. That brought its score since D-Day to 76.5 aircraft destroyed, three probables and 37 damaged. Among the kills was a Messerschmitt Me 262 jet, the first such victory over the new aircraft for either the RCAF or the RAF.

By the end of the war, the squadron had earned many battle honours, including Battle of Britain 1940, Defence of Britain 1940-1941, English Channel and North Sea 1942, Dieppe, Fortress Europe 1941-1944, France and Germany 1944-1945, Normandy 1944, Arnhem and Rhine.

Despite the impressive war record, the squadron was again no longer needed in peacetime. “We were disbanded on July 3, 1945, while stationed at Fassberg, Germany,” said Ferris.

The squadron was reactivated in April 1946 at RCAF Station Saint-Hubert as an air reserve squadron. In the 1980s, it was renamed 401 Tactical Helicopter and Training Squadron until it was disbanded yet again on June 23, 1996. Its current incarnation as 401 Tactical Fighter Squadron came about on June 30, 2015.

Shortly after the reactivation, the Rams deployed six CF-18s to Kuwait as part of the rotation in Operation Impact, the Canadian Armed Forces contribution to the coalition against ISIS. After the Liberal Party came to power in October 2015, it ended Canadian involvement in the airstrikes in Iran and Syria. Soon after, the CF-18 Hornets were recalled to Canada after flying 1,378 sorties in support of Operation Impact.

“We have fought in every conflict that Canada has been involved in since 1918, with the exception of the Korean War,” said Rock.

While the squadron had no casualties during its recent fighting, a hockey sweater with the name McQueen on the back hangs on the wall at Klersy’s. It is a memorial to Capt. Thomas McQueen who died when his CF-18 crashed in November 2016. McQueen, 29, was killed in a training accident when the single-seat jet went down on the Saskatchewan side of the Cold Lake Air Weapons Range. He had 10 years of experience as a pilot and had served in Eastern Europe and Iraq.

“From a young age, drawing jets on his homework through air cadets, he never wavered in his desire to be a fighter pilot,” his family said in a statement after the crash. “Thomas loved speed, whether it was on a boat, his dirt bike or breaking the sound barrier in his jet.”

The sweater is the most recent remembrance of the fighting spirit the Rams have shown through several incarnations over the past 100 years.

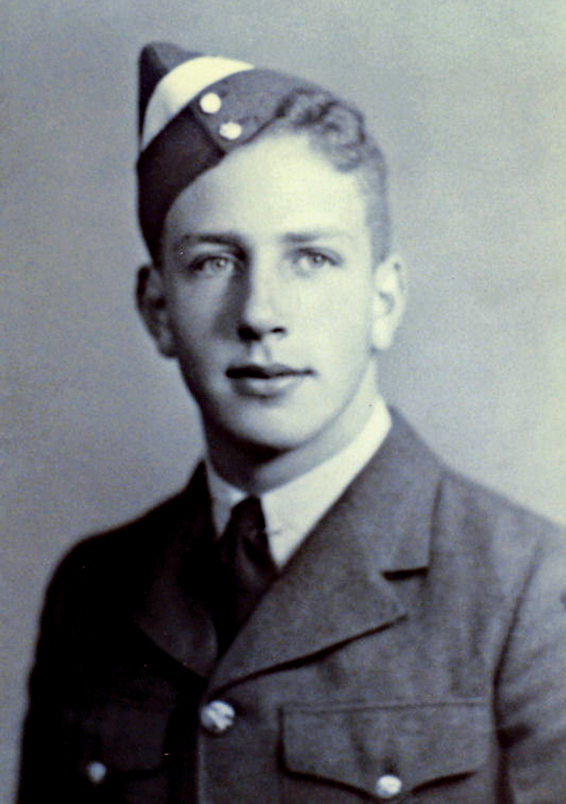

William Klersy rose to commanding officer of 401 Squadron during the Second World War. [Veterans Affairs Canada]

in Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery near Nijmegen in the Netherlands.

Born in Brantford, Ont., Klersy graduated as a pilot from No. 6 Service Flying Training School at Dunnville, Ont., and joined 401 Squadron at Redhill, flying Spitfire Mark IX Bs. By the end of his first month, he had destroyed several enemy aircraft and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. After his first tour of operations, he was assigned to RCAF headquarters. Shortly after, the commanding officer of 401 Squadron was shot down and Klersy was asked to come back as his replacement.

He went on to earn a bar to his DFC and the Distinguished Service Order. His DSO citation reads: “Since the award of a Bar to the DFC, Sqdn. Ldr. Klersy has destroyed or further damaged 90 enemy vehicles, eight locomotives and eight good trucks. He has also destroyed three more enemy aircraft, bringing his total to at least 10 enemy aircraft destroyed. This officer has moulded his squadron into a powerful operational unit that, by maintaining a consistently high standard in every phase of ground or air activity, has set a magnificent example to the rest of the wing.”

On May 22, 1945, Klersy was leading three aircraft departing from RAF Tangmere in England. The trio ran into cloud cover over the Netherlands. According to an official report, Klersy called a turnabout to starboard in the cloud but he turned to port and the other two pilots lost track of him. The wreckage was found two days later with the pilot’s remains still in the aircraft. Klersy was 22 years old.

Advertisement