Eighteen years after he came to Canada for lifesaving heart surgery, Djamshid Djan Popal is sick and in hiding in Afghanistan.

[Courtesy Djamshid Djan Popal]

Djamshid Djan Popal, who came to Canada in 2004 for life-saving heart surgery thanks to donors from across the country, has faced hardship, health issues and physical threats since he returned to his war-ravaged homeland 18 years ago.

Taliban sympathizers wrongly assumed Djamshid’s good fortune was because his father Shafiullah was a coalition informant, a spy, or some other enemy. Shafiullah, a rock breaker, was beaten several times and imprisoned for three months after the country fell to the Taliban in August 2021.

Nine-year-old Djamshid Djan grimaces with pain from his swollen liver during ultrasound tests at the German field hospital in Kabul, Afghanistan, on Thursday, June 17, 2004. [CP PHOTO / STEPHEN J THORNE]

Now largely alone and incognito, Djamshid scrapes a living from menial work as he tries to find a way back to Canada and Canadians, to whom he is eternally grateful. He was nine years old when a medic accompanied him and his dad to Ottawa.

Nine-year-old Djamshid Djan Popal and his father Shafiullah wait in the airport at Kabul, Afghanistan, on Thursday, July 1, 2004, minutes before beginning their journey to Canada. Djamshid hopes to get life-saving heart surgery in Ottawa. [CP PHOTO/Stephen J. Thorne]

He and his father might have stayed in Canada after the surgery, but the boy feared he would never see his mother again, and his father, who had never ventured beyond Afghanistan’s borders before their trip, was not a worldly man.

“I remember every day of it,” Djamshid said in an encrypted audio interview via interpreter from Afghanistan. “I made a very bad decision on coming back to my country. I regretted it a lot for many, many years.

“I was very young and once I got treated, I felt so much better. I thought, ‘wow, now I am enjoying my life as a happy kid; I can just go back home and play and have fun.’ I didn’t know that when I grew up, I would face a lot of challenges.”

The tools and expertise to repair Djamshid’s malfunctioning heart, however, did not exist in Afghanistan, nor in neighbouring Pakistan.

Djamshid’s health issues came to the fore when the Royal 22e Régiment—the storied Vandoos—and 12e Régiment blindé du Canada showed up to conduct a clinic in his village in 2004. The isolated, embattled area hadn’t seen a doctor in about a decade.

Shafiullah brought his sickly son to the schoolhouse into which area residents crowded for treatment of a wide variety of ills—men first; women second. Captain Americo Rodrigues, a Canadian army doctor from Toronto, ran the clinic.

Rodrigues said at the time that, without treatment, the frail boy would be dead inside of three months. His heart and liver were enlarged, signs that his condition was in its final, and potentially fatal, stage. Rodrigues feared the boy was already so damaged that even medical intervention wouldn’t save him.

Shafiullah Djan Popal prays next to his dying son Djamshid on a sheet at the Canadian army field hospital in Kabul, Afghanistan, on Wednesday, June 30, 2004. [Stephen J. Thorne]

The tools and expertise to repair Djamshid’s malfunctioning heart, however, did not exist in Afghanistan, nor in neighbouring Pakistan.

Enter Saddique Khan of Hamilton, Ont. After reading of Djamshid’s plight, Khan, then a Canadian citizen of just three years, spearheaded a fundraising drive aimed at bringing the boy to Canada for the lifesaving surgery he needed—this in the days before crowdfunding campaigns eased the process of raising dollars for such causes. It worked. Some $40,000 was raised.

Along the way, authorities considered taking the patient someplace closer to home. Jewish and Muslim advocates got together on Djamshid’s behalf, but Israel was ultimately ruled out—surgery there came with a near-guarantee of Taliban reprisals back in Afghanistan.

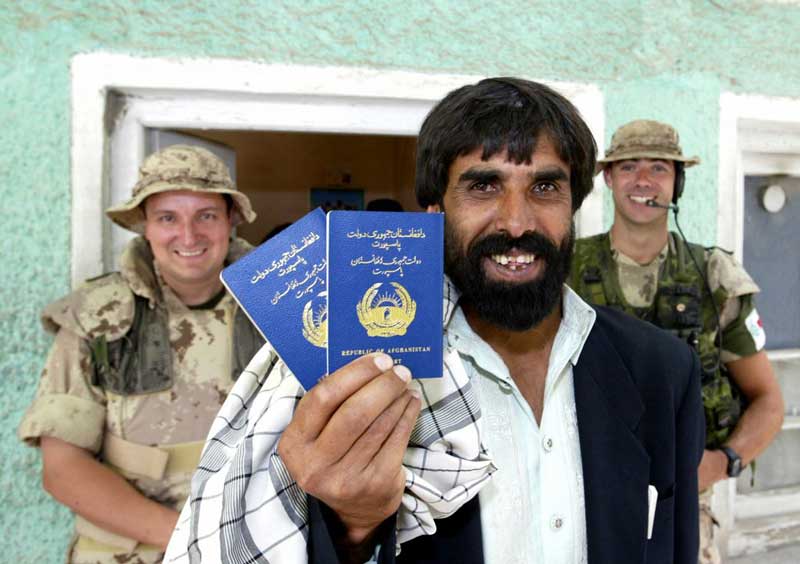

Shafiullah Djan Popal holds new passports for himself and his son Djamshid at the passport office in Kabul, Afghanistan. He is flanked by Capt. Americo Rodrigues (left), a Canadian military doctor, and Cpl. Kevin Comeau, the medic who accompanied the father and son to Ottawa. [Stephen J. Thorne]

Rodrigues and his team of medics and nurses brought Djamshid to Kabul. A mountain of bureaucracy was overcome, and passports were issued in record time.

Djamshid’s condition was stabilized at an ill-equipped children’s hospital, where doctors working in bomb-damaged buildings with sparse resources dispatched Shafiullah to scour the city on foot for 20-cent ampoules of a common medication.

Djamshid’s father was overwhelmed as they departed Kabul, believing for the first time that his son who had been slowly dying for three years would get a second chance at life.

“I can’t imagine how happy I’ll be when I see my son going to school and coming back home,” Shafiullah said at the time. “I can’t imagine how happy I’ll be hearing his words, saying: ‘Mom, I’m very hungry; I need to eat something.’

“Oh Allah almighty, save my child, my sweetheart, my echo, my soul, my shadow. May Allah bless all the Canadian doctors and their families, especially their children.”

Corporal Kevin Comeau, a medic from Tabusintac, N.B., accompanied the boy and his father to the country on Canada Day 2004. They had a hotel stopover in Islamabad, where Shafiullah took the first hot shower of his life. It lasted hours.

In 2021, however, with American and other coalition forces on the way out, the Afghan National Army all but collapsed. Taliban fighters overran the country and took Kabul.

Djamshid was diagnosed at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario in Ottawa, where doctors determined that three of his four heart valves had been damaged by a severe bout of rheumatic fever—an ailment that could have been eradicated with antibiotics readily available most anywhere else. Surgeons at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children repaired his heart.

He was given a supply of medication, including the blood-thinner warfarin, and eventually sent home.

Two Afghanistan tours and 14 years later, Americo Rodrigues recalled in a 2018 interview with Legion Magazine what he described as “a very moving experience” encountering Djamshid.

“He was nine, but he looked six,” said Rodrigues, who retired a major in 2016 after 15 years and was providing civilian contract medical services to the military. “He had a wonderful smile; I still remember that to this day.

“It wasn’t myself who saved him, it was ‘we.’ We were all there. It was an example to me of how kind and compassionate and generous Canadian citizens are.”

His own experience in Afghanistan, he said, reminded him how fortunate we are to live in Canada. Over time, he saw “vast improvements” in living conditions and the foreign-aid system in Afghanistan, including better assistance for children and co-operative programs with Pakistan that allowed transfers of more serious medical cases across the border.

“That was personally satisfying.”

In 2021, however, with American and other coalition forces on the way out, the Afghan National Army all but collapsed.

By Aug. 15, 2021, almost 20 years after Afghanistan-trained al-Qaida terrorists launched the 9/11 attacks, Taliban fighters had overrun the country and taken back Kabul.

Djamshid was already in a refugee camp in Pakistan on a two-month visa, filling out forms, submitting them to the United Nations High Commission on Refugees and Canadian immigration officials—hoping that he could somehow make his way back to the country that had already saved him once.

The UN rejected Djamshid’s application for refugee status out of hand, however, and he says Canadian authorities never responded.

“I cannot support myself here; how could I support a wife and family?”

Like these men outside Kabul, Djamshid’s father Shafiullah broke rocks for a living. [Stephen J. Thorne]

“Welcoming refugees to Canada is an integral part of our country’s long-standing and proud humanitarian tradition,” said Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.

In the Sept. 22 statement, Minister Sean Fraser announced that Canada had accepted its 20,000th Afghan refugee since August 2021.

“Resettling at least 40,000 Afghan nationals is a complex and unprecedented initiative that requires a whole-of-government approach, as well as strong domestic and international partnerships,” said the statement.

“This milestone would not be possible without the support of provinces and territories, resettlement service providers, and Canadians who have sponsored Afghan refugees, donated their goods and time, and helped newcomers settle in their communities.”

Djamshid’s Pakistan adventure came to an end after his visa expired; he went into hiding for a month before Pakistani police found and deported him.

Incapable of heavy labour, he’s prepared mud, stacked bricks and supported the more physically challenging work of building houses at half the compensation rate of his peers.

He completed high school, but couldn’t attend university, primarily because he didn’t want to put himself and his family at further risk by elevating his visibility.

The Afghan doctor who supported him is now in Canada with his own family. He acted as the interpreter for the interview.Djamshid has endured much pain, he said, but his one-time patient is confident he could survive in Canada because of the medicine and variety of jobs here. “In Afghanistan, there is only labour.”

Journalist Stephen J. Thorne (left) and Capt. Americo Rodrigues with Djamshid Djan Popal before he left Afghanistan for his life-saving surgery. [Stephen J Thorne]

On the rare occasions that he goes out, he wears a disguise. He is not married. “I cannot support myself here; how could I support a wife and family?”

He maintains regular communication with people he knows in Canada—including the reporter who first met him in that village schoolhouse 18-plus years ago.

“I’d like to extend my thanks to all the Canadians who supported me and gave me a better life,” he said. “My message to the Canadian people is to please help me to leave this place. This is not a one-day or a one-week issue; this is a lifetime issue.

“I have been suffering and I am suffering. I cannot run away from the current government without your support.”

Advertisement