Canada’s first naval recruits in November 1910. [Canada War Blog]

While Canadians had played an important—and often understated—role in maritime interests between the 17th and 19th centuries, Britain remained the bedrock of protection at sea. From 1903, however, the Royal Navy had pursued a policy of withdrawing forces from the Empire’s distant stations to centralize strength against German naval expansion.

The calculated decision raised questions, with one having the greatest pertinence to Canada: Should the country have a navy of its own?

Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, in power since 1896, thought so. Together with Minister of Marine and Fisheries Louis-Philippe Brodeur, Laurier set about filling Britain’s ever-increasing absence in Canadian waters.

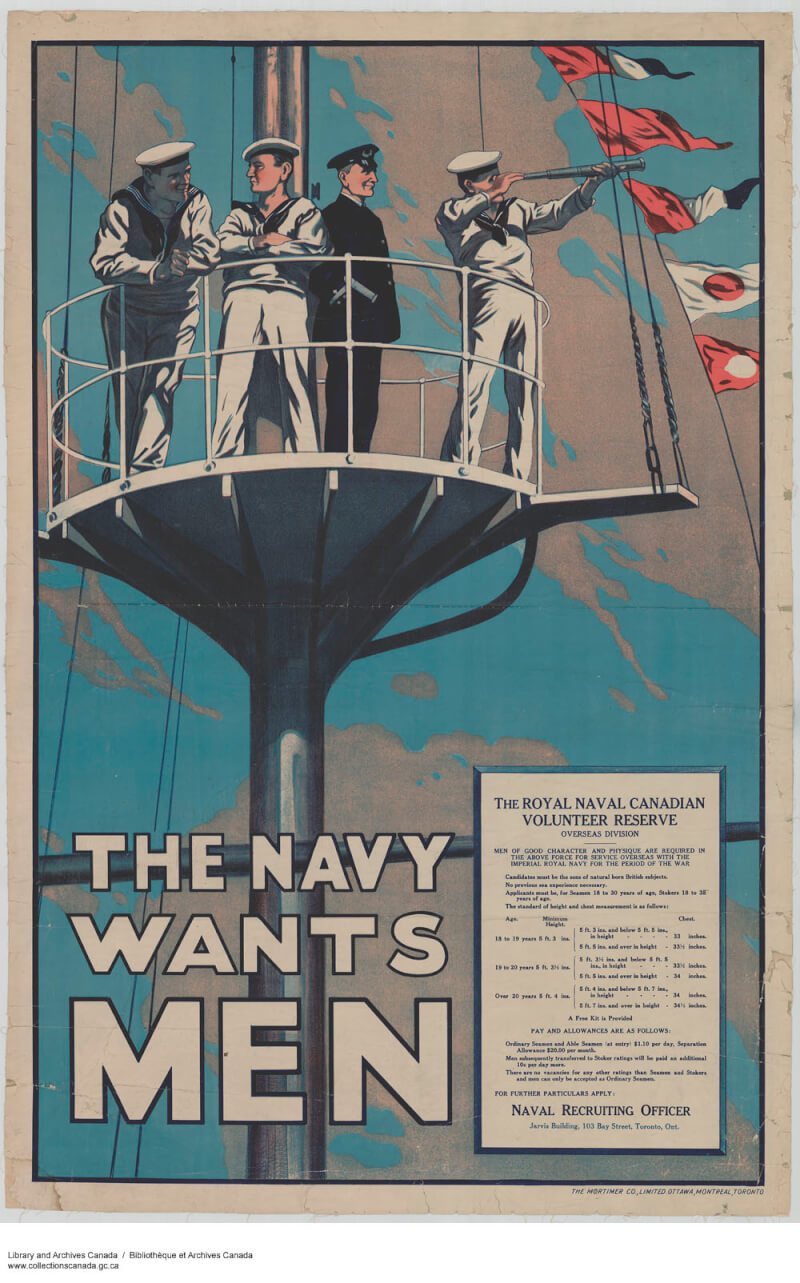

Recruitment poster for the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve. [Library and Archives Canada]

Robert Borden’s Conservative government had other priorities. Instead of bolstering the still-fledgling Canadian Naval Service—redesignated the Royal Canadian Navy that same year—the new PM again turned to Britain for the dominion’s maritime needs. While the RCN remained active, the fleet effectively consisted of two outdated British cruisers, HMCS Niobe and HMCS Rainbow, acquired in 1910 for training purposes.

The First World War proved the wake-up call that Canadian authorities needed. Despite some growth between 1914 and 1918, the RCN’s role—as opposed to that of Canadian and Newfoundland sailors who served in the Royal Navy—paled in comparison to the country’s ground and air contributions overseas, with the Canadian Expeditionary Force and Britain’s Royal Flying Corps, respectively.

Borden was won over. In the immediate postwar period, he began planning a substantial fleet, though it would never materialize under his leadership, which ended in 1920.

For much of the next two decades, the RCN outwardly appeared to teeter on the brink. Only the reforms instigated by Director of the Naval Service Walter Hose seemed to save the still-new institution from an uncertain fate.

Among those reforms was the establishment of the Naval Volunteer Reserve in 1923. Additionally, Hose redirected focus on building a fleet that catered to Canada’s most pressing needs laid bare during the Great War.

Between 1939 and 1945, Canada’s naval strength grew from around 1,800 professional sailors and a dozen ships to some 100,000 personnel and 400 vessels.

There can be no denying the Great Depression’s impact on the RCN, not least the army’s attempts to slash the budget. Nevertheless, starting in 1935, Prime Minister MacKenzie King’s Liberal government saw fit to expand Canada’s naval forces once again.

Of course, the outbreak of the Second World War would necessitate additional growth that far overtook King’s initial plans. Yet, the RCN would meet the challenge in the many dark days—indeed years—to come.

Between 1939 and 1945, Canada’s naval strength grew from around 1,800 professional sailors and a dozen ships to some 100,000 personnel and 400 vessels. Making it the third-largest in the world by the war’s end. New bases, schools, dockyards and other facilities complemented the expansion. Perhaps most importantly, the conflict helped forge a unique identity becoming of the RCN’s new-found stature.

Hurdles still lay ahead in the future, and they continue to today, but Laurier’s vision first embarked upon on May 4, 1910, had finally come to fruition.

Advertisement