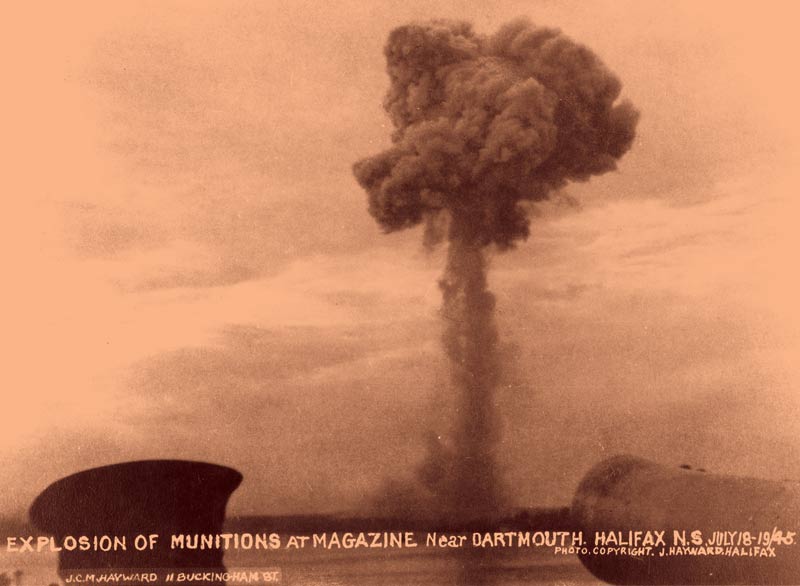

Munitions explode at the Bedford Magazine in Halifax on July 18, 1945. [J.C.M. Hayward/Nova Scotia Archives/1981-517 2]

Captain Owen Robertson had few concerns on July 18, 1945, as he and his wife dined out at Halifax’s Nova Scotian Hotel. Having served as both commander of His Majesty’s Canadian Dockyard and King’s Harbour Master since 1943, the 38-year-old officer originally from Victoria merely wished for a brief respite from his ongoing duties.

The war in Europe—if not the war overall—was over. Royal Canadian Navy personnel and vessels were beginning to transition back to peacetime conditions, a laborious task supervised by Robertson. But not tonight; tonight was his to savour.

That was until an almighty cacophony reverberated across the city’s harbour. The ensuing concussion propelled dust out of the air conditioning units, leaving most stunned patrons and hotel staff with no doubt that something terrible had happened.

Robertson rose, his six-feet-seven-inch frame striking its usual imposing stature, and bolted toward the hotel’s top floor. There, the aptly nicknamed Long Robbie stared in horror as a mushroom cloud formed above Bedford Basin. His fears, alongside those of innumerable locals still haunted by the Dec. 6, 1917, Halifax Explosion, had seemingly been all but confirmed.

Robertson appeared to be witnessing a second Halifax disaster.

Almost 30 years had passed since that cruellest of winter days when two ships, one laden with about 2,925 tonnes of explosives bound for First World War battlefields, collided in Halifax Harbour. The result was the largest human-made explosion at the time.

Some 2,000 lives had been lost and 9,000 more were injured. Even physically unscathed survivors were left traumatized by the atrocious events, long since seared into the collective memories of residents and those in neighbouring Dartmouth. Perhaps unsurprisingly, a proportion were paranoid that history might repeat itself.

Thankfully, it hadn’t—at least not yet. There had, however, been a couple of close calls, itself unsurprising in the strategically vital port brimming with munitions.

On April 10-11, 1942, the Allied freighter SS Trongate, carrying a volatile wartime cargo, was scuttled by HMCS Chedabucto after the merchant vessel caught fire. Using non-explosive practice shells to sink the ship, the Canadian minesweeper’s actions, combined with the early hour they took place, prevented large-scale panic.

Canadian authorities averted another major incident in November 1943, when a fire started in the boiler room of the munitions-loaded American freighter Volunteer. Captain Robertson had joined efforts in battling the inferno, clambering aboard the burning vessel with several first responders and attempting to extinguish the flames. A subsequent explosion launched the dockyard commander out of one of the ship’s hatches, a somewhat lucky escape for him that ultimately claimed the life of another. He then relieved the inebriated and obstructive skipper—albeit through an American liaison officer—and ensured that the Volunteer was piloted out of the danger zone and scuttled. Roberson was awarded the George Medal for his part in the action.

Halifax had been far from quiet since then. The May 7-8, 1945, VE-Day riots had further soured relations between citizens and military authorities, particularly with the RCN. In replacing 2,624 pieces of plate glass, restoring 207 pillaged businesses and repairing an additional 564 establishments, naval ratings had since become, rightly or wrongly, a primary source of city-wide ire, which persisted into the summer.

But, Haligonians had good reason to believe the worst was over. A true catastrophe had failed to materialize, instead confined to fiction via the silver screen. Wartime moviegoers had apparently enjoyed The Yellow Canary, a 1943 film in which a Nazi espionage organization tries to orchestrate a second Halifax disaster. The plot was deemed improbable, and was, but the movie nevertheless proved relatively successful. It was just a story, after all; a bit of harmless entertainment.

A far more likely, if similarly explosive, finale to the conflict awaited.

The Bedford Magazine, an ordnance storage facility nestled against its namesake basin roughly six-and-a-half kilometres from downtown Halifax, had been built in 1927, initially for all military branches before becoming an exclusively RCN site.

Positioned on a rocky, wooded slope near Burnside, authorities had expanded the facility by mid 1943. It boasted a series of brick buildings surrounded by earth and concrete ramparts, the bunkered design intended to ensure that if one structure exploded, the others would be secure.

The magazine, which employed around 500 personnel in late 1944, received stores via water and rail. Two principal jetties in the north and south served inbound and outbound vessels, each with sheds for storage and pumps for firefighting.

When proper procedure was adhered to, the fence-enclosed site was as safe and efficient as any that dealt with ordnance could be—except these weren’t ordinary times. The end of hostilities in Europe had brought about a rush to de-ammunition surplus ships and demobilize their crews as quickly as possible, a politically motivated decision that seldom accounted for the strict regulations.

The rules had once stipulated that only one vessel could unload its arsenal onto a jetty at a time; now, in mid 1945, up to three ships were jostling for space while their deadly cargo littered the wharves. The recent closure of the St. John’s, Nfld., Magazine further normalized laxity as its stocks were shipped to Bedford.

With little room left inside, naval personnel stacked approximately 80 depth charges, 400 hedgehog anti-submarine bombs, cordite charges, anti-aircraft shells and small-arms ammunition on the south jetty, its overflow stowed on adjacent barges.

Bedford Magazine had all the makings of a proverbial powder keg. Elsewhere, tinder was provided in the form of bone-dry grass and brush amid a heatwave.

Just a spark was needed to light the flame.

Able Seaman Henry Craig of Mosside, Ont., might have believed the bloodshed was, or at least was about to be, over. He perhaps thought he had survived the worst conflict in human history, one that had claimed the lives of 45,000 Canadians and Newfoundlanders.

Between 6:30 and 6:40 on the evening of July 18, 1945, the 33-year-old was on guard duty in the magazine compound when he spotted a fire raging on the south jetty, apparently spreading fast.

“I’m going down to see if I can put it out!” he shouted at a nearby comrade as he darted toward the blazing wharf.

It was already too late. Within seconds, Craig was engulfed in an explosion that flung his body 180 metres inland; authorities found his remains three days later.

[Naval Museum of Halifax]

In the meantime, white-hot fragments and burning propellants cut through the air in every direction. Personnel were knocked off their feet and buildings turned to rubble. Within the wider radius, houses were knocked off foundations, windows shattered in Rockingham and other municipal communities, and the initial report could be heard 45 kilometres away, akin to the rumble of a distant thunderstorm.

Reporter Jeff Jefferson witnessed a fiery cloud rising into darkened skies. He had been using his binoculars by sheer coincidence, likening what he observed to a “sheaf of wheat.” Shortly after, the odd spectacle “mushroomed into a ball of reddish flame, and a huge ball of black smoke soared into the air above it,” he wrote.

It was the same horrific sight that Captain Robertson could see.

Halifax Harbour was awash with myriad vessels—destroyers, corvettes, frigates, minesweepers, submarines and smaller craft—

raising anchor and making for the Narrows where, three decades earlier, the epicentre of the last disaster had occurred. It now served as an escape route out of the Bedford Basin to open waters.

Despite the mass seabound exodus, the fire boats James Battle and HMCS Rouille steered toward the danger. There, they confronted the magazine’s burning stocks nearest the shoreline while, inside the facility, scores of personnel mobilized to douse flames with buckets, hoses and anything else remotely usable.

Their combined efforts were hampered by cooking-off ammunition and shrapnel careening through the air, a threat that persisted for the duration of the struggle. Naval firefighters, together with their municipal and volunteer counterparts, nevertheless braved the inferno, their wounds attended to by a single nurse.

They had a common goal; if the fire reached one of the main bunkers housing 50,000 depth charges, Halifax might cease to exist.

“Some of the experts,” the journalist Jefferson wrote of the avoided scenario, “claim everything would have been levelled right down to Point Pleasant Park.”

It was, in other words, a race against time, the alternative being a horrendous repeat of the 1917 disaster.

Captain Robertson knew this, too, having left his hotel dinner to take command at the scene. He had barely taken stock of the situation when a reinforced concrete building blew up, hurling him into a pond and out of immediate harm’s way for what seemed like the second time in his charmed life.

Long Robbie extricated himself from his watery soft landing and got back to work. During the ensuing hours, he maintained order where possible, “hopping from jeep to ditch when discretion demanded it.” His praise was reserved solely for those firefighters caught in the fray, “trying to save a big

magazine…loaded with explosives.”

And the night was only just beginning.

A mushroom cloud forms over the Bedford Magazine as munitions explode—and the aftermath.[Yarmouth County Historical Society/Nova Scotia Archives/1981-515 1/Wikimedia]

Ace Foley, a radio broadcaster for Nova Scotia’s CHNS station and, on July 18, the announcer for the baseball game at Halifax’s Wanderers Grounds, knew something was amiss. He had heard the explosion and seen the pillars of smoke. He now watched as the stands began to empty of spectators.

But the game continued—and so did Foley, continuing his play-by-play as a palpable uneasiness fell over the remaining crowd. Soon he was frequently interrupting his commentary to broadcast orders for personnel to report to base. Finally, if belatedly, the game was cancelled.

Across two cities, where confusion and uncertainty reigned supreme, uniformed Canadians did what they could to assist—and in doing so, began the process of restoring their relationship with locals. On a Halifax-Dartmouth ferry, personnel prevented fear-stricken passengers from jumping overboard. Others, including Russell Harkness of the Provost Corps, drove civilians out of urban districts to open spaces such as Halifax Common, where glass—a horrendous killer and maimer when shattered in 1917—was less of an issue.

At 9 p.m., naval headquarters instructed all people living between North Street and Bedford Basin to evacuate. The mandate was later extended to more than half of the city, as far south as Quinpool Road. Similar orders were given to every Dartmouth resident and in total 125,000 people abandoned evening meals for congested roads and streets out of a potential blast radius.

Smaller explosions frayed the nerves of temporary refugees spending the night in fields, parks and public gardens. Emergency shelters were opened in both cities, supported by the Canadian Red Cross. At the Halifax Armoury, representatives distributed some 3,700 blankets to those who sought sanctuary and an additional 700 to citizens sleeping outdoors in Dingle, Francklyn and Point Pleasant parks.

Most Haligonians chose to leave the peninsula entirely, weaving around smashed windows only recently repaired after the VE-Day riots. Cars, heaving under the weight of valuables and furniture, navigated passengers past outbound pedestrian traffic. Vast swaths of Dartmouth were transformed into a ghost town.

Yet, a strange sense of order prevailed throughout the evacuations. Residents voiced their fears, false rumours spread freely, but the overall panic level seemed muted. For many, not least the thousands gathered on Citadel Hill, watching the drama play out before their eyes was one last adventure of the war.

Others felt differently, especially following a series of large explosions that jolted the senses of countless civilians. Jefferson recounted three such blasts through the night and into the early hours of July 19, the worst of which occurred at 3:55 a.m.

“I remember seeing the blazing red sky,” he recorded. “Within ten minutes, as we hugged the ground, another explosion punctured the dawn.”

The latest report—caused when the inferno reached 360 depth charges and bombs—could be heard as far away as Yarmouth County, N.S., 350 kilometres away. Meanwhile, the cloud reflection created by the flames was visible on the provincial highway from Truro to New Glasgow and beyond to Antigonish.

But, with the fading smoke came the realization that the crisis had finally peaked. Whatever had happened at Bedford Magazine, authorities had regained control.

Captain Robertson’s first responders, including the fire boats James Battle and Rouille, had successfully prevented a catastrophe. Fighting through a maelstrom of bullets, shells and more—all in the absence of enemies—the men and women who endured the relentless ordeal had prevailed. This was not a second Halifax disaster.

As residents slowly, cautiously, filtered back, they were afforded a chance to survey the destruction wrought. Several houses had been left in ruins, their roofs crumbled and their doors caved in. Barrington Street looked like it had on VE-Day, if not worse. At the northernmost tip in Africville, a Black community hard hit back in 1917, the damage was again extensive, if less severe. North Dartmouth had likewise suffered a battering from successive shockwaves.

But, compared to what it could have been—and, at least according to some, almost was—the sight that greeted most civilians came as a relief. Windows and mirrors could be replaced. Minor breakages could be repaired. And $4 million worth of compensation would eventually be provided to all claimants within three years.

Crowds gather around broken glass on Barrington Street in Halifax. [J.C.M. Hayward/Nova Scotia Archives/Wikimedia]

Lacking substantive evidence for any one theory, the naval inquiry conceded that they were “unable to attribute direct blame to any person or persons.”

The luckiest Haligonians returned home to little more than a cold dinner from the night before. One understandably distressed woman lamented over the loss of her heirloom china. Another found a dozen eggs splattered on the kitchen floor.

It was a different story at Bedford Magazine, where approximately 50 per cent of the buildings had been destroyed or badly damaged. The south jetty, where the fire had started, no longer existed, save for a scattering of charred and broken wood. A significant proportion of stores saved from the flames, meanwhile, had instead been flooded to prevent a major escalation. Of greatest concern was the live ordnance strewn well beyond the site’s confines, hidden in undergrowth or submerged underwater. The sudden emergence of a minefield would ultimately require a five-year recovery operation; between July 18 and Oct. 1, 1945, some 2,000 tonnes of ammunition was shipped and dumped at sea.

Miraculously, however, Henry Craig was the incident’s sole fatality, his deeds recognized with a posthumous Mentioned in Dispatches.

That the Bedford Magazine explosion had inflicted so few casualties was almost entirely due to the courage, fortitude and professionalism of all first responders. Hungry, thirsty and exhausted from their efforts, the firefighters deserved a rest.

Captain Robertson radioed naval headquarters and put in a request for sustenance. “What we would have welcomed,” he said, “was lettuce and ice cream—maybe sandwiches—but good old Central Victualling Depot sent us a slab of beef and a sack of raw potatoes.” Furious, the sleep-deprived commander radioed in again.

Through open channels, Roberton cursed the person responsible, threatening to have the culprit’s “balls for a necktie.”

Ice cream and sandwiches soon arrived.

About half of the magazine’s buildings were in ruin following the blasts. [Naval Museum of Halifax]

What caused the Bedford Magazine explosion?

A naval inquiry found that overstocked stores, unsatisfactory regulation adherence, supervision and enforcement issues, and the wooden construction of the jetty were among the factors that contributed to the inferno and subsequent explosions. Aside from theories, however, officials stopped short of asserting an original fire source.

Investigators noted that the most “probable origin” was “unauthorized smoking and carelessness with respect to disposal of ignited smoking materials.” Other suggestions ranged from spontaneous combustion to a barge stove fire to the striking of primer caps during “the shifting of insecurely piled ammunition.”

Lacking substantive evidence for any one theory, the naval inquiry conceded that they were “unable to attribute direct blame to any person or persons.” The entire matter was dropped. Thus, even today, no widely excepted explanation has emerged.

Like recollections of a thunderstorm from the night before, the excitement of the July 18-19, 1945, Bedford Magazine explosion inevitably waned. Lives had not been upended in the same way as on Dec. 6, 1917, ensuring the incident became little more than a footnote in history—a far better outcome than the alternative.

Despite that reality, remarked reporter Jefferson in an article written shortly after the events, “tonight lightning proved that it can strike twice in the same place.”

Advertisement