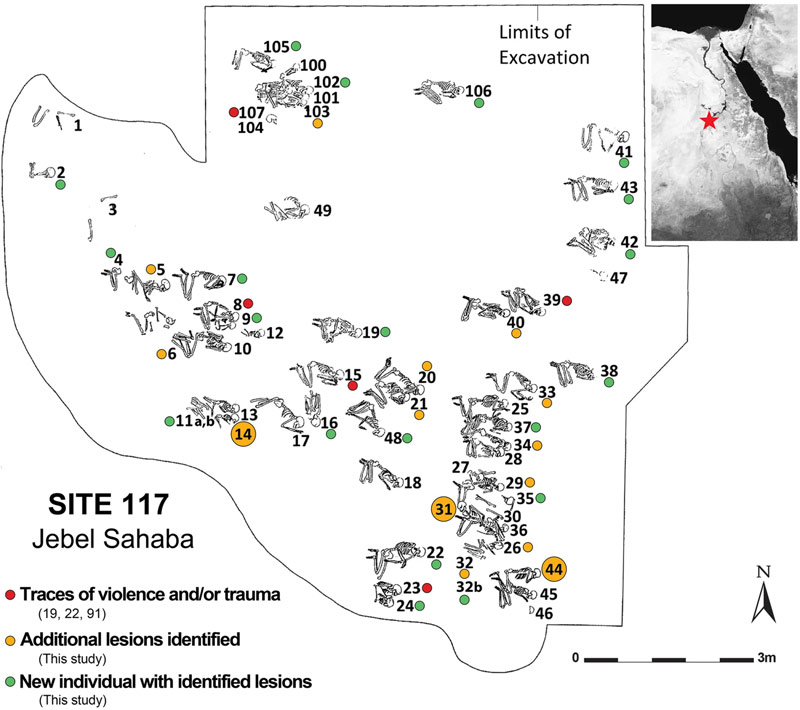

Pencils mark the locations of possible arrow or spear injuries among the skeletons of Jebel Sahaba. Previously believed to be evidence of one of history’s oldest battles, these injuries are now thought to be proof of reoccurring conflict and violence. [Wendorf Archives/British Museum]

New evidence uncovered long after a prehistoric cemetery was discovered in Sudan suggest that its inhabitants weren’t killed in what was believed to be one of humankind’s earliest known battles but may instead have died over the course of protracted warfare.

Furthermore, the study by paleoanthropologist Isabelle Crevecoeur of the University of Bordeaux, France, and her team of anthropologists, geochemists and prehistorians suggests the ongoing series of raids, ambushes and other violence was likely attributable to an issue all too familiar to 21st-century society: climate change.

The cemetery at Jebel Sahaba was first excavated in the 1960s, but the new study, published May 27 in the journal Scientific Reports, says scientists at the time missed evidence that some of the 61 skeletons they excavated had both new and old battle wounds when they died at least 8,000 years before the rise of Egyptian civilization. The cemetery is estimated to be 13,400 to 18,600 years old.

“We dismiss the hypothesis that Jebel Sahaba reflects a single warfare event.”

“Over 100 previously undocumented healed and unhealed lesions were identified on both new and/or previously identified victims, including several embedded lithic [stone] artefacts,” wrote the researchers, who used new microscopic equipment and techniques to venture where their predecessors couldn’t go.

“Most trauma appears to be the result of projectile weapons and new analyses confirm for the first time the repetitive nature of the interpersonal acts of violence,” said the paper. “Indeed, a quarter of the skeletons with lesions exhibit both healed and unhealed trauma.

“We dismiss the hypothesis that Jebel Sahaba reflects a single warfare event, with the new data supporting sporadic and recurrent episodes of interpersonal violence, probably triggered by major climatic and environmental changes.”

Working at the British Museum in London, where the remains are stored, Crevecoeur and her team analyzed hundreds of bones, including those of 21 individuals with previously undetected lesions indicating projectile impacts or broken bones; another 16 were found to have both healed and unhealed injuries.

Some skeletons appeared to have been disturbed by later burials, further supporting the researchers’ hypothesis that those buried at Jebel Sahaba had encountered multiple incidences of violence.

The victims were hunters, fishers and gatherers—foragers—and the number and types of injuries did not discriminate between men, women and children. More than half had suffered projectile impact wounds.

“The only difference is related to what might be close combat,” Crevecoeur told CNN. “Women have more parry fractures of the forearm and men more fractures of the hand. In a close-combat event, women might more instinctively try to protect themselves (with arms) while men might fight more with their hands.”

Children, some as young as four or five, suffered most of the head wounds—blunt-force traumas and/or projectile impacts. Artifacts included many stone projectiles, unretouched flakes and micro-flakes whose “association to weaponry is indisputable.”

“Their diversity in both size and shape suggests the use of several types of weapons, particularly light arrows but also much heavier arrows or spears,” said the paper. “The use of points with oblique or transverse distal cutting edges appears to indicate that one of the main lethal properties sought was to slash and cause blood loss. The fact that many were found inside the volume of the skeleton also indicates their efficiency at penetrating the body.”

Those found at the site are likely to be the ones that had detached themselves from their shaft, it said.

The conflicts took place at the end of the Late Pleistocene and beginning of the Holocene periods, which the paper says were marked by major climatic changes. Their impact on human populations remains little understood, but it is known that there was a major drought at the time.

While the researchers cannot definitively say what caused the fighting, they noted that such climate extremes would have affected food, water and other resources.

They suspect different groups of people who were once distributed across a wide area sought refuge from the harsh climes in the Nile Valley, where wildlife would have been more plentiful—and competition more intense as the region became more populated. Later flooding from an overflowing Lake Victoria would only have exacerbated their problems.

The study’s findings enrich understanding of the contexts in which violence emerged among foragers.

“Violent behavior in past and present hunter-gatherer societies appears to vary, in part reflecting the period, culture and the level of organization of mobile and semi-sedentary societies,” said the paper, adding other finds suggest that warfare can encompass all forms of antagonistic relationships from feuds, individual killings, ambushes, raids and trophy-taking to bloody clashes and larger armed conflicts.

“The level of warfare can vary, with some conflicts being all-encompassing, constant and deadly, while others are episodic events of various intensity that occur sporadically. At Jebel Sahaba, the co-occurrence of healed and unhealed lesions strongly supports sporadic and recurrent episodes of interpersonal violence between Nile valley groups at the end of the Late Pleistocene.”

The study’s findings enrich understanding of the contexts in which violence emerged among foragers, according to Luke Glowacki, a Harvard University anthropologist.

“They provide additional evidence for an emerging consensus that foragers, just like agricultural peoples, had interpersonal violence in the form of raids and ambushes,” he said.

Jebel Sahaba is one of about four burial sites, each marked by distinctive stone tools or technologies that suggest separate groups converged on the region. Radiocarbon dating confirmed it is also the oldest.

“We do not know of any other cemetery at that time which shows such a high rate of people injured and killed.”

The paper notes that evidence of conflict is not uncommon in the Nile Valley. The oldest documented case dates to about 20,000 years ago in Wadi Kubbaniya, where the partial skeleton of a young adult male showed signs of violence.

Scientists have also documented embedded stone and healed fractures at the region’s Wadi Halfa cemetery. But none exhibits evidence of early widespread violence like the cemetery of Jebel Sahaba, where 26.2 per cent of the studied remains had signs of new traumas at death and 62.3 per cent had healed and/or unhealed traumas.

“We do not know of any other cemetery at that time which shows such a high rate of people injured and killed,” said Thomas Terberger, who specializes in the archaeology of hunting and gathering at Germany’s University of Göttingen.

Location of the cemetery at Jebel Sahaba within the Nile Valley, as well as a map of the excavated area and burials. [Wendorf Archives/British Museum]

The cemetery has been cited as a key example of the emergence of violence and organized warfare triggered by territorial disputes since it was discovered by American archeologist Fred Wendorf in 1964. Many have long regarded it as the earliest evidence of organized warfare between humans.

Using cutting-edge anthropological and forensic methods, Crevecoeur’s team was the first to thoroughly reassess Wendorf’s findings, nearly six decades later.

The investigators looked at the cemetery’s makeup and the profile of its residents to see if a pattern emerged that might cast more light on its nature.

“Should the cemetery reflect a single warfare event, an unbalanced demographic profile (e.g. the overrepresentation of a certain sex or age group less likely to die otherwise) is probable,” said the paper.

No such overrepresentation existed. Among those whose sex could be identified, for example, 48.7 per cent were females and 51.3 per cent were male.

Furthermore, the positioning of the wounds—both frontal and back—do not support the conduct of face-to-face battles.

“A catastrophic single mass burial is highly unlikely and not supported by the archaeological evidence and the demographic analysis,” concludes the study.

“While acknowledging the possibility that the Jebel Sahaba cemetery may have been a specific place of burial for victims of violence, the presence of numerous healed traumas and the reuse of the funerary space both support the occurrence of recurrent episodes of small scale sporadic interpersonal violence at the end of the Pleistocene. Most are likely to have been the result of skirmishes, raids or ambushes. Territorial and environmental pressures triggered by climate changes are most probably responsible for these frequent conflicts between what appears to be culturally distinct Nile Valley semi-sedentary hunter-fisher-gatherers groups.”

More work is needed, added the scientists.

New podcast series now available! Go to legionmagazine.com/frontlines.

Advertisement