The Avro Lancaster bomber nicknamed Sugar was one of few to survive more than 100 missions. [Courtesy of the Chinese Canadian Military Museum]

It was just six weeks before the end of the Second World War when the telegram arrived for the Lee family in Winnipeg, all capital letters, like someone shouting to be heard above a rising internal wail: REGRET TO ADVISE THAT YOUR SON FLYING OFFICER JIM GEN LEE…IS REPORTED MISSING AFTER AIR OPERATIONS OVERSEAS MARCH TWENTY THIRD STOP LETTER FOLLOWS.

It still carries impact after seven decades, individual grief suddenly writ large, one telegram of the 17,000 received across the country by families whose sons and daughters and husbands died serving in the Royal Canadian Air Force during the war.

It was among a little collection of carefully preserved papers—slivers of heartache, really—that ended up in a box in the Chinese Canadian Military Museum in Vancouver,

a box opened by curator Catherine Clement.

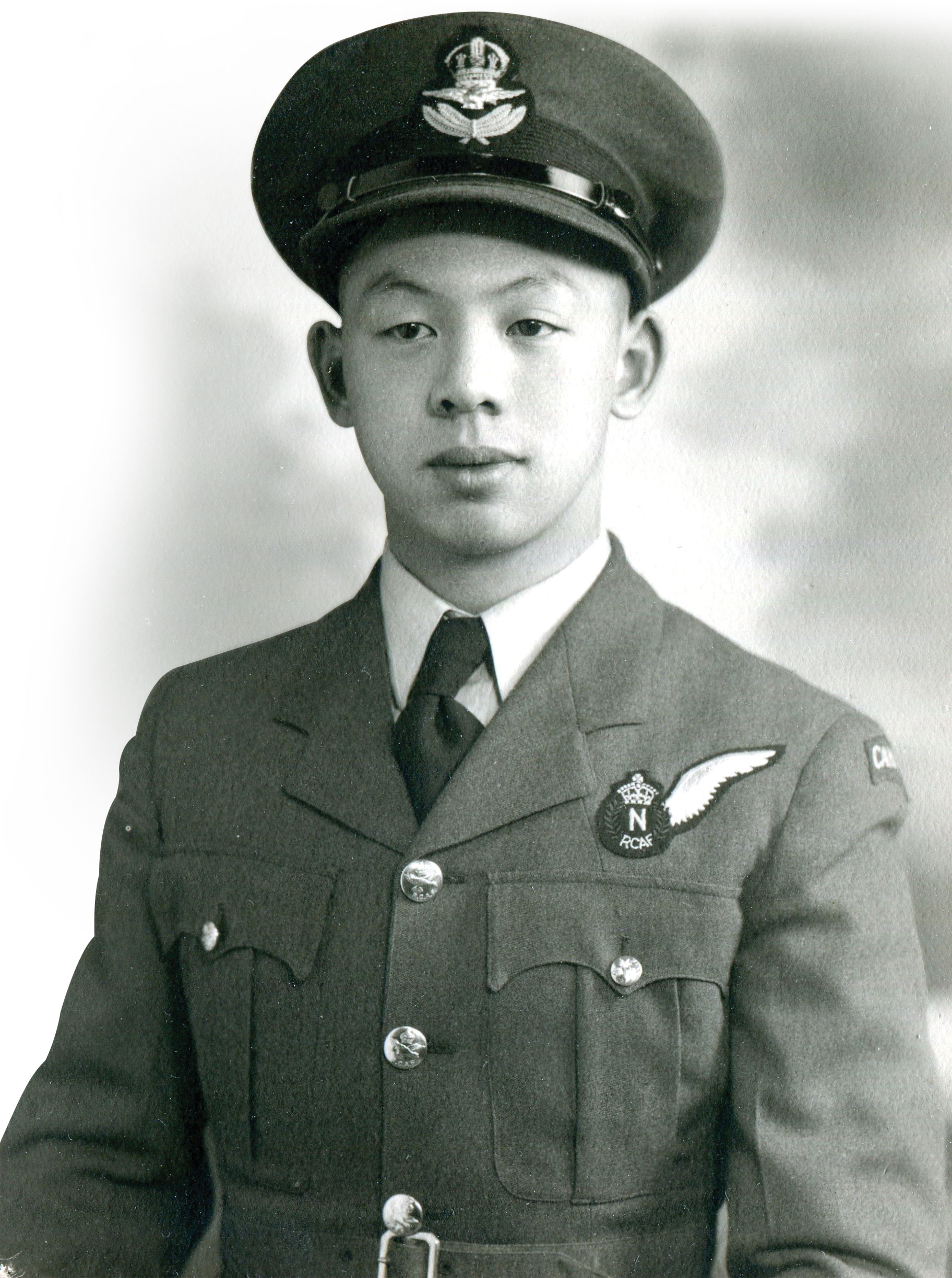

RCAF members (from left) Wilfred Brooks, Jim Gen Lee and Robert Little were among the seven crew members lost on a daylight raid. [Courtesy of the Chinese Canadian Military Museum]

“They’re just little pieces of paper, but if you read them, you understand what they went through,” said Clement.

The letter that followed—to Mrs. Chin Shee Lee from Royal Air Force No. 101 Squadron leader K. Flint—is longer, but does not provide much more information. The aircraft—a Lancaster III DV245, designated SR-S (for Sugar)—failed to return to base. “No messages were received from the aircraft after takeoff, and nothing has so far been heard of it or any member of the crew.

“There is always the possibility that they may have come down by parachute or made a forced landing in enemy territory, in which case news of this would take a considerable time to come through, but you will be immediately advised of any further information that is received.”

Flint noted that although Lee had been with the squadron only a short time, he was keen and “a most efficient Navigator of aircraft.”

Her son’s effects, said the letter, would be held “until better news is received, or in any event for a period of at least six months” before they would be sent home.

Lee, 22, was one of three RCAF members in the crew of seven lost in a bombing raid of Bremen, Germany, on March 23, 1945, along with air bomber Wilfred Brooks, 21, of Edmonton and pilot Ralph Robert Little, 23, an American serving with the RCAF.

For a long time, said Clement, no one really knew what happened to Sugar or its crew. “There were theories it could have been shot down by a Messerschmitt, or it could have been friendly fire, or something else. But something happened that was catastrophic.”

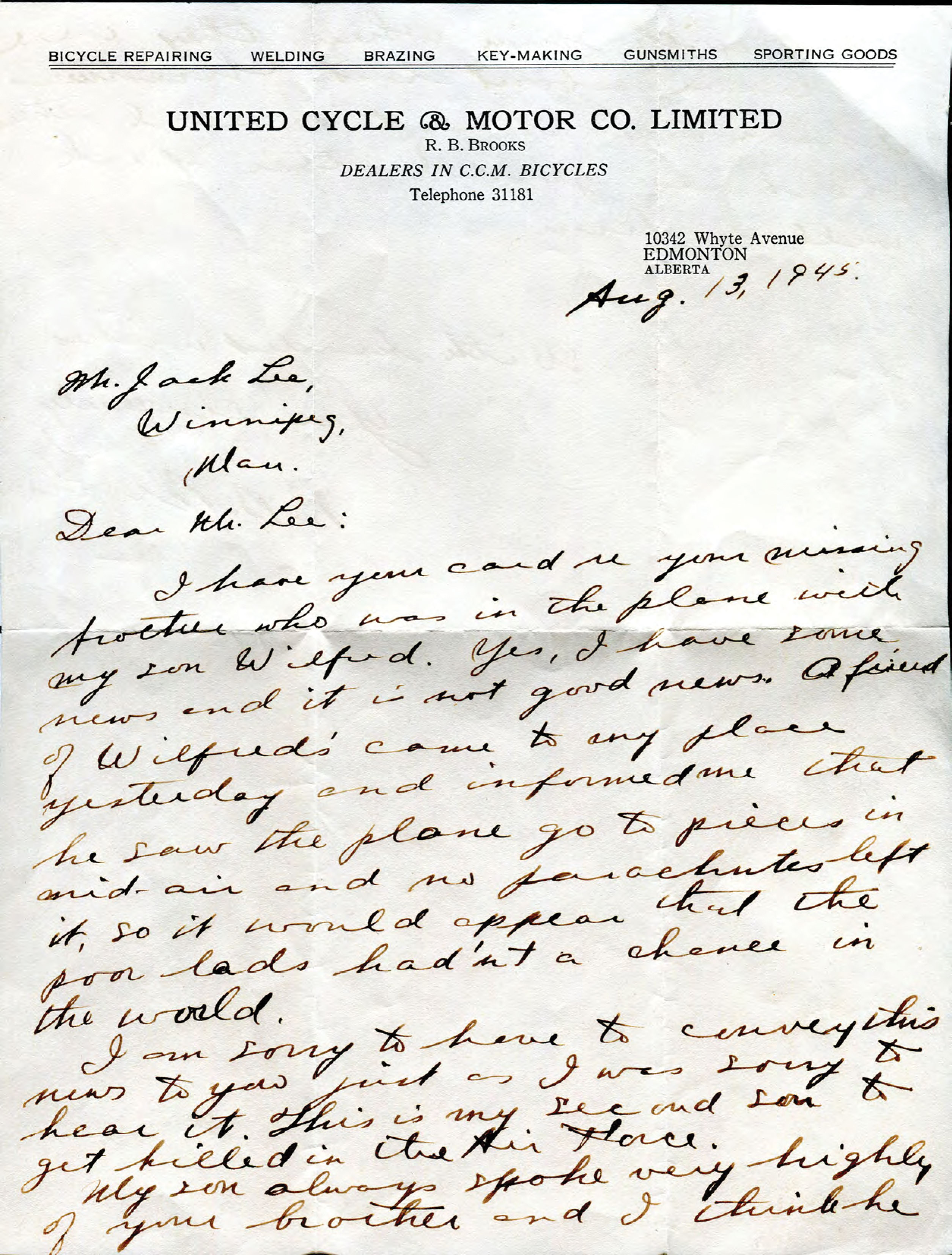

A letter dated Aug. 13, 1945, informs Lee’s family of his fate. “Yes, I have some news and it is not good news,” writes crew mate Wilfred’s father, Raleigh Brooks. “A friend of Wilfred’s came to my place yesterday and informed me that he saw the plane go to pieces in mid-air.” [Courtesy of Chinese Canadian Military Museum]

Months passed with no official word, so Lee’s brother Jack contacted other grieving families, and received two responses in August.

“We must not give up hope, miracles can happen,” wrote Mrs. R.S. Little of Lockport, N.Y., on Aug. 5. “Please God, maybe we will have our boys returned to us…. I am glad to know your parents have other children, at least one, to ease their pain and grief. Bob was my only child.”

Then came devastating news from Raleigh Brooks of Edmonton.

“I have some news and it is not good news. A friend of Wilfred’s came to my place yesterday and informed me that he saw the plane go to pieces in mid-air and no parachutes left it, so it would appear that the poor lads hadn’t a chance in the world. I am sorry to have to convey this news to you, just as I was sorry to hear it. This is my second son to get killed in the Air Force.”

“These are really heartbreaking letters,” said Clement, letters that show the emotional devastation on the home front. “These three families were bonded together by this story.”

Though they shared a lifetime of anguish, the families had some resolution when the bodies of the crew were located in 1949. They had been buried in a Russian cemetery in Germany, and were subsequently interred in the British Sage War Cemetery near Oldenburg, 50 kilometres west of Bremen, and provided headstones by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. But whatever brought them to this end?

Lee’s uniform sports the RCAF navigator’s brevet. [Courtesy of the Chinese Canadian Military Museum]

Crews from that bombing raid are all listed on flight manifests and logs of 101 Squadron, which was based at the RAF Ludford Magna airfield about 200 kilometres north of London. It was one of the “secret squadrons” equipped with transmitters, code-named ABC and called airborne cigars, used to jam radio signals of the Luftwaffe. But using it meant breaking radio silence, making the aircraft easier to track and attack; consequently, 101 Squadron had among the highest casualty rates of Bomber Command, which lost more than 12,000 aircraft and registered 55,573 of its 125,000 personnel killed, including more than 10,000 Canadians.

Lee was one of the tens of thousands of RCAF personnel who served on RAF bomber and fighter crews. It was his third operation for 101 Squadron, a daylight bombing raid on railway bridges at Bremen and Oeynhausen, over which war materiel travelled to and from shipyards, aircraft factories, motor transport plants and an oil refinery.

Ironically, Lee was in a lucky aircraft: Sugar was on its 119th operation, one of only 35 RAF Lancasters to complete 100 or more sorties.

Sugar’s first crew suggested a nickname: The Saint, after the antihero Simon Templar created by novelist Leslie Charteris. Templar was also featured as a Nazi-fighter in a popular radio program of the day. Rear gunner Eric Bickley supplied the sketch for the nose art—a haloed stick figure astride a red bomb—as reported in Ton-Up Lancs by Norman Franks in 2005.

Sugar was a popular aircraft. “Like other crews, we became very attached to our Lancaster,” bomb aimer Gerry Murphy said in Ton-Up Lancs. “We did not like flying in another aircraft when she was in for service and we did not like other crews flying her when we were on leave. I think that she had only one vice: a reluctance to lose height.” One night, “we brought her back well holed and our ground crew were disgusted. They almost regarded her as their personal property.”

“Give me Sugar any time,” said Flying Officer Reg Paterson of Hamilton, the pilot for the Lancaster’s 100th operation, a night raid on Hanover on Jan. 5, 1945. “Despite its age, it can do as well as any aircraft I know, and I think it climbs better than most. I’d be content to finish my tour in it.” At that point, DV245 had logged 720 hours flying time, had weathered several engine changes, and bore flak scars from anti-aircraft guns on the ground and bullet holes from fighters in the sky.

On March 23, 1945, 101 Squadron contributed 24 of 117 Lancasters sent to attack bridges at Bremen. Two did not return; in another irony, the other was piloted by Paterson on his 30th mission, flying the lead in LL755 SR-U (Uncle). Just after Uncle had delivered its payload, the plane was hit and its port wing severed. It fell like a rock. Five of the seven crew made it out of the aircraft, but two did not survive; one fell out without his parachute and the parachute of another did not open. Paterson was taken prisoner and spent about a month at Stalag Luft 1 at Barth before the camp was liberated by the Russians.

What happened to Sugar was less clear, despite the unofficial eyewitness who talked to Raleigh Brooks. In 2011, Alf Woodier, a flight engineer with 101 Squadron, wrote a review of Ton-Up Lancs and added more details to the saga of Sugar: “On a daylight Opp (Bremen) 23 March 1945 mid-morning, I saw a Lancaster off our port wing under attack. I could not read its identification, but saw that it was on fire with pieces of aircraft falling from it. I also saw two men leave but did not see any chutes and with the tail and rear fuselage burned away, it began to turn end over end until it hit the ground in a huge fireball. I did know later that day that my friend [Flight Engineer] A. Clifton had not returned and was missing, but many years passed before I read that the Lancaster that I had seen that day was his aircraft, 101 Squadron’s S-Sugar.”

Lancaster OL-H of No. 83 Squadron RAF—similar to 101’s SR-S—waits to take off on the “Thousand-Bomber” raid to Bremen, Germany, on June 25-26, 1942. Like Lee’s Lancaster, this aircraft was also lost. [Wikimedia]

More than 7,000 of the heavy bombers were produced for the RAF, and half were lost on operations. Sugar was 101 Squadon’s last lost Lancaster, Franks reported in Ton-Up Lancs.

Lee’s parents, devastated by their loss, returned to China, leaving their four surviving children behind, said Jim Lee, who was named for his uncle. The surviving children scattered after the war, and the third generation knows little of the family history during the Second World War, “much to my chagrin,” said Lee, who lives in Arizona. “It was never talked about.” He learned the bare bones of the story in the mid-1960s when the city of Windsor, Ont., bought a Lancaster to serve as a memorial. Lee’s father Louis contributed to its purchase.

Relatives of Wilfred Brooks still live in Edmonton, where the fourth generation now runs United Cycle, the business bought by Raleigh Brooks, air bomber Wilfred’s father, in the 1930s.

The second Brooks son mentioned in the letter, Keith Bishop, was with 78 Squadron, which contributed to 749 aircraft on the last bombing raid of the industrial city of Bochum, Germany, on Nov. 4, 1944. Five of the seven crew were RCAF. All were killed when their Handley Page Halifax bomber crashed, likely near Margraten. They are commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial in Surrey, England.

The family’s loss was not a topic of conversation when Wilfred Brooks, today a co-owner of the cycle business, was growing up. He does not even know whether he was named in honour of his cousin.

“It was never talked about, never really dealt with,” said Brooks. “A lot of that history really is lost.” His cousins’ wartime documents and stories were not passed down through the family. Commemoration, he said, “is an itch in my life that still needs scratching.”

Brooks recently began collecting information for a family memorial—an antique rifle, likely from the Boer War, mounted with pictures of the brothers (including Tom, who died trying to rescue a drowning girlfriend in 1951), accompanied by written histories—to be displayed in the boardroom of United Cycle. “It helps to bring a little closure.”

For the modern generation, at least.

Advertisement