The odds of recovering from a wound in the Second World War were nearly twice as high as in the Great War.

Doctors attributed the improvement to better treatment for shock and blood loss; antibiotics to fight infection; improvements in surgery; and prompt and efficient medical and surgical treatment.

Although the killing machines of this war were just as murderous, medical advances cut the mortality rate to 66 per thousand from 114 per thousand in the First World War.

The men and women of the Canadian Medical Services handled more than two million wartime casualties. The service grew from only 40 permanent medical officers in 1939 into a medical corps for all three services employing 5,219 medical officers, 4,172 nursing sisters and 40,000 other ranks and ratings.

Medical breakthroughs made during the war provided a lasting legacy to civilian health systems that continue to benefit patients today.

A soldier is transported for medical treatment in late-war Germany. [Jack H. Smith/DND/LAC/PA-113872]

Antibacterial forces

“I thought I was going to die [while in isolation due to an infection] but I gradually got better with the help of penicillin. I came out and a fellow…called out ‘Look, Bull is not dead after all.’”

—Stewart Hastings Bull, blinded and maimed in Normandy

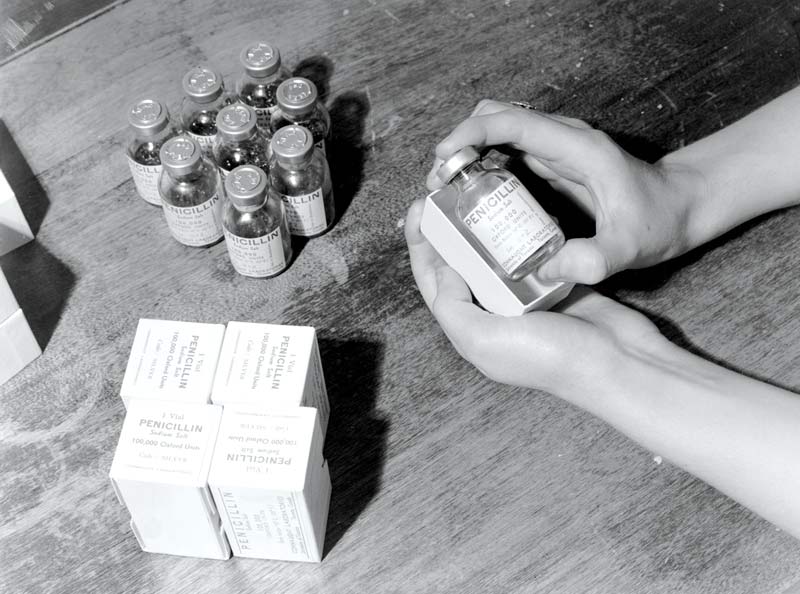

Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin in 1928, but for the next decade British scientists struggled to produce enough even for research.

The mould grew in a film only a few millimetres thick, and it took 2,000 litres of the underlying culture to provide enough to treat a single serious infection. In 1940, the world’s entire supply was injected into one mouse.

Developed in the 1930s, antimicrobial sulphonamides—commonly known as sulfa drugs—were sprinkled on wounds in the field and administered during first aid and in hospitals at the start of the Second World War. As a result, wrote W.R. Feasby, author of the Official History of the Canadian Medical Services, blood poisoning, so common in the First World War, was rare in the Second.

One bacterium can multiply to more than 30,000 in five hours. Sulfa slows bacteria’s ability to divide, allowing the body’s white blood cells to slowly defeat the infection. But penicillin outright kills bacteria. It gained a reputation for snatching dying patients out of the grave.

But this miracle drug could not be developed in the country where it was discovered. British labs were targeted in the war and there was a shortage of material needed for further development.

In 1941, a British team travelled to the United States and Canada hoping to find help in mass producing the wonder drug. The result was an international collaboration of governments, research institutes and drug manufacturers to ensure a robust supply for the war effort.

The Allies shared discoveries, including a better growth medium, a process to grow penicillin in huge vats rather than on trays, isolation of more potent strains, improvements in purification, and methods of converting liquid penicillin to solid.

“Two British officers and myself were the guinea pigs. I was back in the line in five weeks.”

The drug was hailed in a 1943 Maclean’s article as “one of the most powerful antibacterial forces ever discovered.”

The Department of Munitions and Supply provided $2.5 million to fund mass production. By D-Day, a score of companies, including Canada’s Connaught Laboratories, were churning out billions of units of penicillin every month.

Penicillin destined for the front is carefully packed at Connaught Laboratories in Canada. [Harry Rowed/National Film Board of Canada]

Colonel S.W. Thomson, a Seaforth Highlander wounded in the thigh in Sicily in 1943, was part of the field trial of the wonder drug conducted by Fleming himself and a colleague.

“Two British officers and myself were the guinea pigs,” Thomson is quoted in an article in Canadian Military History. “I had it in powder form through my wound. I was back in the line in five weeks.”

On a hospital ship bound for England, critically ill Edward George McAndrew was accidentally given an overdose of penicillin; a mistake, said his surgeon (who just happened to be Fleming’s wife), that undoubtedly saved his life.

Penicillin was used to treat trench mouth, pneumonia, skin infections and to treat and prevent wound infections. It was also used to treat venereal disease, sparking a debate about which should be treated first, the soldier from the battlefield or the bordello. The latter made more sense, said Richard Conniff in an article for HistoryNet, “since you could cure a soldier and send him back to the front in a matter of days.”

It has been estimated that penicillin saved the lives of some 100,000 men in Europe, preventing gangrene and perhaps 30,000 limb amputations and halving the rate of infection in penetrating wounds to the head. There was a noticeable drop in the death rate from abdominal wounds in Normandy compared to Italy, where less was available.

The work on penicillin at the University of Toronto and Connaught Laboratories had a lasting effect “of national importance,” noted Feasby, for it laid the groundwork for pharmaceutical research in Canada. “A new industry was rapidly brought into being.”

Surgeons at the front

“In the last war, we brought the wounded to the hospital; in this war, we are bringing the hospitals to the wounded.”

—U.S. Office of War Information, 1943

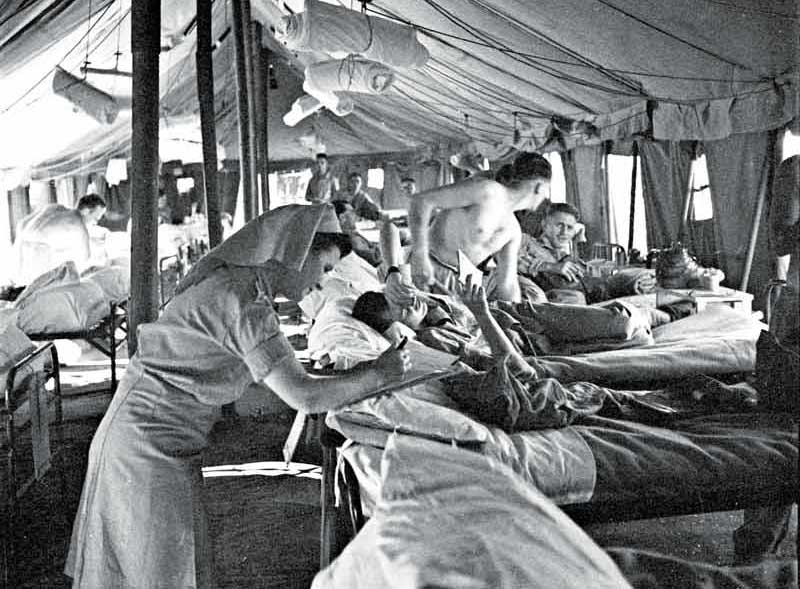

The goal of the Canadian Medical Services was to make sure casualties received the right treatment as soon as possible, whether they were wounded on land, at sea or in the air.

By 1945, the Canadian Army Medical Corps had an elaborate evacuation system to get the wounded back to the appropriate place for treatment, beginning with stretchers and ambulances, field ambulance units, and for the more seriously wounded, hospital trains and ships or special flights. The medical services operated a score of general hospitals.

Through casualty clearing stations, serious cases were sent on to more than 20 Canadian general hospitals, a handful of convalescent hospitals, a hospital specializing in neurology and another specializing in plastic surgery.

A patient is treated by Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps personnel at a field dressing station in Germany in March 1945. [Donald I. Grant/DND/LAC/PA-192875]

But early in the war it became obvious that soldiers were dying of survivable wounds. The casualty evacuation system couldn’t get them to surgeons fast enough and field ambulance units near the front were not equipped for complex surgical cases. When overwhelmed with casualties, speed was of utmost importance.

“Four ambulances, they back them all together; and they leave a little hole in the middle for an operating room. Each ambulance will take four wounded men and they operated on them; fix ’em up, put them in an ambulance, away it goes; and another one backs in,” said Roy Armstrong, who served in a field ambulance unit in Normandy.

More complex cases had to be sent by ambulance to hospitals in the rear—often miles and minutes too far.

The solution was field surgical units. Surgeons, anesthetists, support staff, equipment and supplies for a few dozen surgeons were carried in trucks that would follow armoured divisions as they moved.

The invasion of Sicily in 1943 was the proving ground. Surgeons in two units were at work within 24 hours of landing and performed 229 major operations. They set up where they could, including tents and “a filthy stable…a wine cellar, then a house, a tent…a cathedral and finally a school,” one reported to senior officers. They handled abdominal wounds, serious wounds to the arms and legs, sucking chest wounds, severe burns of tank crews and cases of gas gangrene.

The system proved successful and was soon improved. Field dressing stations, transfusion units and surgical units were combined to form advanced surgical centres.

“They keep close to the front by leapfrogging each other,” wrote Peter Stursberg in a 1943 Maclean’s article on front-line hospitals. The war diaries of 13 Canadian Field Ambulance note during the attack on the Hitler Line in Italy, the advanced surgical centre progressed 145 kilometres in six moves, often coming within enemy artillery range, while admitting 497 cases. “We’d move about every 10 days,” recalled Lieutenant Gertrude Dickey.

Although the mortality rate hovered at around 20 per cent, surgeons saved the majority of patients they treated, many of whom would not otherwise have survived evacuation to hospitals in the rear.

“There is no doubt at all that the soldier in this war has a better chance for survival…. And from what I saw the Canadian soldier has the best chance of all…due to advanced surgical centres and field hospitals. Bringing surgery to the front line saved many Canadian lives,” Stursberg wrote in “Front Line Hospital.”

Care for sailors and flyers

“We were closed up in action stations all the time. Half of this crew was seasick…the smell wasn’t all that good, all the portholes were closed and all the doors were closed.”

—Harvey Douglas Burns/The Memory Project

The navy and air force had smaller medical systems catering to the unique health care needs of their services.

At the beginning of the war, the navy had no hospitals. “Not even a bed!” lamented the official historian. But by the end of the war, there were 2,000 beds in nine naval hospitals, plus facilities aboard ship.

Crews suffered seasickness, accidents, combat wounds and hypothermia…and sometimes there was no sick bay aboard ship.

A surgeon, who had broken ribs himself, had to amputate a leg on a rolling deck.

“We didn’t have any sick bay attendant or first aid on board,” signalman Barney Roberge recalled in a Memory Project interview. The second degree burns on his hands, face and stomach were not properly tended for four days until his ship reached port. “My blisters…was starting to turn funny colours.”

Royal Canadian Navy medical officers were frequently transferred so all would get sea experience. It was challenging work, as they could not replenish supplies at sea, so had to make do with what was at hand, sometimes working in cramped and hellish conditions.

A surgeon, who had broken ribs himself, had to amputate a leg on a rolling deck. “A large shot of brandy and a padded stick for the patient to clench his teeth on, served in the absence of anesthetic,” said S.T. Richards, quoted in Bill Rawling’s Death their Enemy: Canadian Medical Practitioners and War.

Survivors of ships sunk in the Atlantic were often plucked blue and shivering from the water, so navy doctors developed effective treatment for hypothermia. They learned frozen extremities should be thawed or warmed very slowly, and that putting unaffected limbs in warm water caused blood vessels in affected limbs to dilate, hastening the warming process.

The powers that be needed some persuading to approve a separate medical branch for the Royal Canadian Air Force, despite arguments air personnel were exposed to unique risks, such as blacking out at high altitude and deafness due to noise levels in aircraft and maintenance hangars.

But the decision to make Canada home of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan clinched the deal. Specialists were needed for medical examinations of thousands of recruits, and treatment and research proceeded on myriad health conditions unique to air service, including crash injuries.

The air force treatment hospitals developed during the war varied in size from a few beds in sick quarters at remote training stations to hundreds of beds in wards in civilian or military hospitals and purpose-built facilities. By the end of the war, the RCAF also had 11 convalescent hospitals across the country.

RCAF mechanic Romeo Bourgeois was in a plane crash in Neepawa, Man., on April 27, 1943. “I went to hospital and stayed there for five months.” After release, “I wanted to get back to the air force right away.” And a jeep was waiting to take him back.

Nursing Sister D. Mick reads a patient’s chart during rounds at No. 15 Canadian General Hospital in El Harrouch, Algeria, in August 1943. [Frederick G. Whitcombe/DND/LAC/PA-141498]

Better blood

“Blood serum sent overseas from Canada and given by patriotic Canadians is saving thousands of lives.”

—Captain Jack Jennings, who lost a leg liberating Rome/The Elgin Military Museum

Prior to the Second World War, few civilians had ever heard of blood banks. Or blood drives. But they were essential to saving lives on the battlefield, in aid stations and in operating rooms.

Transfusions had saved the lives of soldiers suffering great blood loss and shock during the First World War. That knowledge passed to civilian hospitals after the war. But transfusions were expensive—the blood supply was limited due to lack of donors and blood could not be stored for long.

In 1939, the looming war focused attention on developing a reliable supply for military transfusions.

Even though blood typing was standardized, some patients inexplicably died from transfusions using compatible blood types. In 1940, Karl Landsteiner of the Rockefeller Institute discovered that Rhesus (Rh) factor was also important. Even though the blood type matched, when Rh-positive blood was given to a person with Rh-negative blood, their blood produced antibodies to the transfused blood, causing a serious reaction. Military blood typing protocol was adjusted accordingly.

Canadian researchers were put to work solving the problem of blood storage. Whole blood could not be stored for long, and while frozen blood plasma was easier to transport and store, it was not ideal for military transfusions because it took about half an hour to thaw and could not be stored for long afterward.

Charles Best, familiar to Canadians for his work in diabetes research, demonstrated that low blood pressure from shock could be improved by administering blood serum. He and his team at Connaught Laboratories developed a process to separate serum from whole blood and dry it for easy transport. It did not require refrigeration, could be stored for long periods and reconstituted with water for transfusions when needed.

Best also suggested the government task the Canadian Red Cross Society, which had branches across the country, with blood collection. Its volunteer-based Blood for the Wounded campaign collected 2.3 million donations at 600 clinics. A similar Blood for Britain program was run by the American Red Cross.

“The blood transfusions have saved lots and lots of lives.”

From D-Day to July 26, 1944, the Canadian military used 18,000 pints of blood and 15,000 pints of plasma, a bit of which went into saving Corporal Frank Oke, who required six transfusions and lost a leg after his tank was hit July 25.

“The blood transfusions have saved lots and lots of lives,” he said, quoted on the Elgin Military Museum website.

By 1945, human serum albumin, a type of globular protein, had been developed. It is in whole blood that is rich in red blood cells that carry oxygen and is considerably more effective than plasma alone, especially in surgery. It is used to replace lost fluid and help restore blood volume in trauma, burn and surgery patients.

After the war, the Red Cross continued collecting voluntary blood donations, this time for use in civilian hospitals, a program that continues to provide blood products to Canadians today, through Canadian Blood Services and Héma-Québec.

“The greater availability and use of transfusion therapy as far forward as regimental aid posts is credited by doctors as one of the three factors that cut the toll of deaths from wounds in the Second World War,” says the Official History of the Canadian Medical Services.

Rankin of the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps administers a blood transfusion to a wounded soldier in Montreuil, France, in September 1944. [Lieut. Frank L. Dubervill/DND/LAC/PA-128234]

Wound management

“I said ‘What did you do?’ And he said: ‘I’ve cut a piece out of your cheek and swung it over to the right side of your nose. Your nose was gone.’”

—Stewart Hastings Bull

Surgeons of the Second World War capitalized on advances in transfusions and antibiotics to advance techniques for saving more lives and salvaging more limbs.

Orthopedic surgeons preserved limbs that in earlier wars would have been amputated. And when they did amputate, new techniques saved more limb function. Technical advances also allowed treatment of once-hopeless abdominal and chest wounds.

But one breakthrough benefited every soldier, sailor or air crew member who needed surgery.

In 1940, surgeon Angus Campbell Derby, who served in an advance surgical centre, learned of a breakthrough made by a surgeon in the Spanish Civil War that was “more significant than penicillin in reducing hospital mortality.”

It wasn’t enough to remove the projectile, sprinkle the wound with antiseptics and stitch it up. Bullets and shrapnel tear into flesh, carrying mud, dirt, skin and clothing into tissue surrounding the wound and damaging muscle. “The resulting devitalized muscle becomes an ideal medium for bacterial growth,” Derby wrote in Not Least in the Crusade: the Memoirs of a Military Surgeon.

Canadian surgeons adopted the technique, called debridement. They enlarged entrance and exit wounds to clear away all dead tissue and left the wound open, covered by a pressure dressing, for about a week. Then, “if the wound was clean, it was closed.”

“The results were indeed rewarding,” he wrote, adding the hospital mortality rate from infection and gangrene was a third of that of the First World War.

The technique is now the standard approach to wound management.

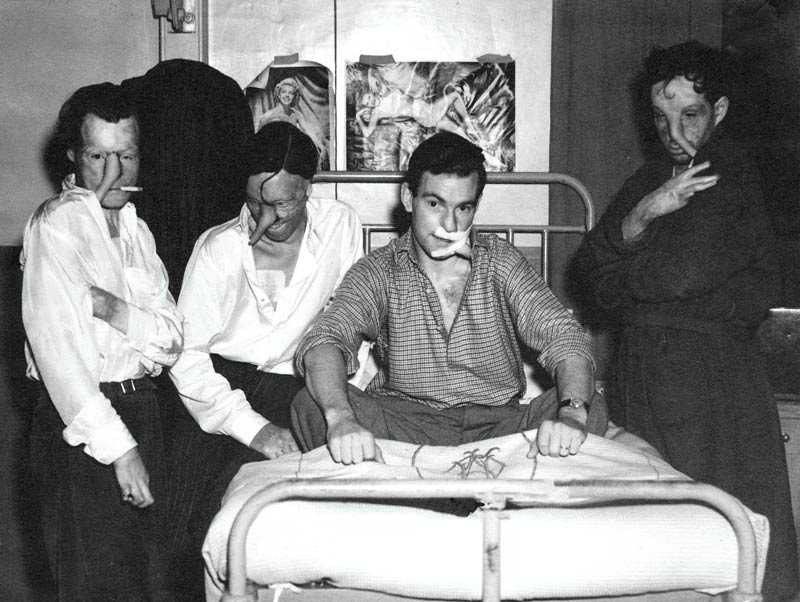

Out of the inferno

In the First World War, a severe burn was a death sentence. Medical staff could not do much more than keep burn patients pain-free until they died of shock or infection.

Breakthroughs in shock treatment and antibiotics in the Second World War allowed thousands of pilots, sailors and tank crew to survive severe burns, and advances in plastic surgery and rehabilitation, which included mental health therapy, prepared them for return to service or civilian life.

“They converted wrecks of bodies into a recoverable state.”

The Battle of Britain produced a steady stream of burn victims. When hit, aircraft fuel tanks would explode, fire flashing over pilots, burning their faces, neck and hands. An estimated 4,500 Royal Air Force crew were pulled from burning aircraft, of which 3,600 sustained serious burns. About 200 who had lost most or all of their facial features were known as ‘the faceless ones,’ according to “The Guinea Pig Club” on HistoryNet.

“The doctors who looked after them, plastic surgeons mostly, were wonderful. They converted wrecks of bodies into a recoverable state,” said Stewart Hastings Bull, wounded at Caen, in a memoir published on The Canadian Letters and Images Project website.

Patients at Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead, England, underwent breakthrough surgical techniques to reconstruct their facial features. [Queen Victoria Hospital/East Grinstead Museum]

Burn patients had to be isolated from other wounded patients and extra care taken to prevent the spread of infection. A burn treatment unit was established at Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead, near London, with pioneering New Zealand surgeon Archibald McIndoe at its head.

Surgeon Archibald McIndoe pioneered many new surgical techniques. [Queen Victoria Hospital/East Grinstead Museum]

RCAF medical officer and plastic surgeon Ross Tilley joined the hospital in 1942. More than a quarter of the patients treated at the hospital were Canadian—enough to justify congregating them in their own wing in 1944, with Tilley as chief surgeon.

Tilley prepared his patients well. Each had a personalized reconstruction plan. They knew exactly what to expect prior to and during surgery and rehabilitation. Patients might need as many as 50 surgeries spread out over years.

Tilley reconstructed noses and ears, reformed eyelids, re-established facial features. At the time, the treatment was so ground-breaking that patients must have thought it science fiction.

RCAF plastic surgeon Ross Tilley shares a smile with Flight Lieutenant Marjorie Jackson, matron of the hospital’s Canadian wing. [Queen Victoria Hospital/East Grinstead Museum]

Unburned skin could be harvested to replace burned skin. But large patches of skin cannot just be shaved off and plunked down on the wound—the transplanted skin will die without a new supply of blood.

So skin was “walked” from one area to another. A flap was cut from healthy skin and left attached at one edge, like a page in a book. The flap, called a pedicle, was folded to protect it from infection; blood vessels on the attached edge kept it alive. The pedicle’s free edge was then stitched into an incision elsewhere and left to establish a blood supply at the new site.

The process could take weeks and would need to be done multiple times if the healthy skin was far from the burn. All that time, patients had to remain in uncomfortable positions so as not to disturb the pedicles, which could connect leg and arm, or arm and neck or shoulder and nose.

One patient complained about being used as a guinea pig. In 1941, patients formed the Guinea Pig Club, which went a long way to boosting morale through camaraderie.

Tilley believed in the importance of psychological well-being to healing, and the role of community in mental health. The Guinea Pig Club gave burn patients the courage to socialize, and careful preparation of East Grinstead residents ensured a welcome reception. Villagers were told what to expect: terrible scars, missing ears and eyelids, deformed hands. And they were asked not to stare or comment. It was a success.

“Here Canadian boys can walk into Bill Gardiner’s restaurant and be greeted by Bill as if they were walking into the main-street café back home in the old days,” wrote Flying Officer Jack Calder, a journalist from Chatham, Ont., whose face wounds were treated at the hospital.

Breaking points

“Each time a man goes through an ordeal, though he overcomes fear and does his job, the memory…is pushed into his subconscious and the gate is barred and guarded by will. But the day comes when there are too many ordeals; the will breaks and the gates fly open and fear and torment come swirling through.”

—A medical officer in Germany, speaking to CBC’s Matthew Halton on March 5, 1945

The breakthrough for military mental health during the Second World War arose less from developing science than the sowing of seeds that flowered fully decades later. It was a change in attitude toward mental health.

Lessons were learned from shell shock of the First World War, but traumatic brain injury, depression and anxiety were still not well understood and it was decades before post-traumatic stress injury was recognized.

This time round, psychiatric casualties were expected. So the Canadian Neuropsychiatric Hospital was established at Basingstoke, England, in 1940.

But there were senior commanders in all three services who saw psychological breakdown as a character defect, such as a lack of moral fibre, and a matter for discipline, not medical treatment. Others thought some soldiers were just susceptible to mental trauma and wanted psychiatrists to weed them out.

Many Canadian military psychiatrists disagreed, arguing that intense battle could cause a psychological breakdown in even the mentally fittest. They advocated far forward psychiatry—treating cases quickly before symptoms became entrenched, then returning the men to combat.

A treatment centre was established in Italy within earshot of battle—and was quickly overwhelmed. For the first time, ambulances in Italy “carried casualties who bore no visible wounds…victims of what was officially termed ‘battle fatigue,’” wrote Farley Mowat in And No Birds Sang. Mowat, who was with the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment throughout the Italian campaign, graphically described the psychological breakdowns of comrades.

Mowat suffered post-traumatic injury during the campaign in Italy. [Lieut. Frederick G. Whitcombe/LAC]

“Stark naked, he was striding through the cordite stench with his head held high and his arms swinging…singing ‘Home on the Range’ at the top of his lungs. The Worm that Never Dies had taken him,” wrote Mowat. He wrestled with the worm himself after the Battle of Ortona, describing “the inexorable way it liquefies the inner substance of its victims.”

In Italy, 16.9 per cent of battle casualties—5,020 cases—were neuropsychiatric. During the war, about half the men treated near the front were returned to their units, but a large number were judged unable to continue with combat roles and had to be assigned behind the lines.

In Northwestern Europe, treatment for men with battle exhaustion included 24 hours of sedation, followed by two days of rest and talk therapy. Severe cases were evacuated to England, where treatment included stronger drugs and, occasionally, electroshock therapy.

Private A.R. Beaton provides some accordion music for three members of the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment, (from left) Lieutenant Farley Mowat, Private J. Dalton and Captain J.A. Baird, near Motta, Italy, on Oct. 3, 1943. [Lieut. Jack H. Smith/DND/LAC/PA-190825]

By the end of the war, psychiatrists had persuaded senior commanders that battle exhaustion was not malingering, lack of moral fibre, nor an attempt by unwilling soldiers to escape the war.

“Although there are wide variations in the capacities of normal soldiers to withstand stress, every soldier has his breaking point,” wrote Colonel F.H. Van Nostrand, senior psychiatrist overseas, in a postwar analysis. It was a big step forward.

Advertisement