![Second World War veteran Gib McElroy. [PHOTO: SHARON ADAMS]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/access1.jpg)

It’s unusual to catch Gib McElroy in his room at the Perley and Rideau Veterans’ Health Centre in Ottawa. He’s out visiting his friend, Charlie, at bingo or physiotherapy, a veterans’ council meeting or taking in one of the centre’s many activities. He’s gone so much that his wife and his friends have learned to leave messages for him to call them when he’s got a minute.

On this day the 90-year-old veteran does have time for a chat in his cozy room. Memorabilia on the walls and a comical statuette of a clown provide a welcome splash of colour on a grey winter day.

McElroy survived three crash landings during the Second World War; in 1943, at age 19, he parachuted to safety when his Lancaster was shot down. He was captured and taken to a prisoner of war camp, endured starvation and a forced winter march to another camp before escaping as the Russians moved in.

Back in Canada, McElroy settled down to family life. He worked as a locomotive fireman, survived a train wreck, was a master car salesman and eventually retired. In his 80s he started having falls, once shattering an elbow. After a couple of respite stays at the Perley, as it is fondly called, he applied for long-term care and moved there in 2013.

“People think you get in here because you’re on borrowed time,” he said. “I lose no time in setting them straight.” He is among the last 2,500 so-called ‘traditional’ veterans (Second World War and Korean War veterans) supported today by the federal government in long-term care. Grateful to the hundreds of thousands who volunteered to serve during the Second World War, the federal government committed to helping ex-service personnel resettle into civilian life, a promise later extended to Korean War veterans, but not to “modern” veterans—those who served after the Korean War. As there was no public health care system then, a network of 40 federal facilities was established for veterans’ treatment and rehabilitation. “As veterans’ needs evolved to be more chronic and domiciliary in nature, the nature of Veterans Affairs Canada’s program evolved to what it is today: long-term care,” said Janice Summerby, media relations adviser.

With the dawn of public health care in the 1960s, provinces assumed responsibility for their residents’ health care, including long-term care. Federal facilities were gradually transferred to the provinces, though they have retained their veterans’ culture and today are fondly referred to as ‘veterans homes.’

A funding agreement guarantees priority access in provincial facilities for traditional veterans eligible for long-term care support from Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC). Provinces fund medical costs, and charge patients for meals and accommodation. With some exceptions, VAC pays for meals and accommodation for traditional veterans who meet its eligibility criteria. The federal department also provides enriched services, such as extra nursing hours, and art or music therapy programs.

There’s a fear that when the last of the traditional veterans passes away, so will the veterans’ homes, since priority access to long-term care has not been extended to modern veterans. Some worry the veterans’ culture will evaporate, as veterans become outnumbered in community facilities, special programs starve for funding and staff, experienced in veterans’ health issues, disperse. “Once the infrastructure supporting these specialized veterans’ homes is shut down, it will be next to impossible to reconstruct,” said veteran Duane Daly, a member of the Perley Rideau Veterans’ Health Centre board of directors.

“There are now thousands of community facilities across the country providing these services,” said Summerby. “Many veterans are choosing to stay in long-term care facilities in their own communities so they can remain close to loved ones.” Veterans Affairs pays the full cost of care of modern veterans with service-related disabilities “in their community near family and social support services.”

![Jack and Norma Watts. [PHOTO: SHARON ADAMS]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/access2.jpg)

Centralized veterans’ long-term care is a thing of the past. Former federal veterans’ homes across the country have been busy planning how to ensure that the last traditional veterans continue to receive high quality care as the federal program winds down. Some facilities are planning how to survive in provincial health care systems already struggling with strained long-term care budgets and growing demand. Some are making a concerted effort to maintain their veterans’ culture.

In 2013, VAC estimated there were 91,400 Second World War veterans and 9,900 Korean War veterans. Most of these men and women are in their 90s. Modern veterans number 594,300, average age 56. As local populations of Second World War veterans decline there are fewer veterans qualified for priority access beds. In 2012, only 2,595 of 3,133 VAC-supported priority access beds were occupied.

No one knows exactly when the last priority access bed will close. The last First World War veteran died at age 109; all Second World War veterans will most likely be gone in about 20 years, the last of the Korean War veterans in the 2040s.

Staff at Camp Hill Veterans’ Memorial Building in Halifax expected a diminution in 2011, but it hadn’t appeared by fall of 2013, though the wait list had dwindled. But Veterans Services Director Elsie Rolls, who has been at Camp Hill for 12 years, notes other changes. Veterans are coming into long-term care older and frailer. The average stay is about four months, down from 22 in 2005. It’s a cross-country trend attributed to veterans’ desire to age at home, coupled with the growth in the number of assistance programs, including VAC’s Veterans Independence Program.

“Veterans will receive excellent care until the very end of their life—and duration of… Veterans’ Services at Camp Hill,” a 2012 planning document promises. Camp Hill’s 175 veterans are housed in seven wings with separate dining and activity rooms. There’s a garden, a pub and a chapel. Care has been taken to ensure Camp Hill feels like home, not a hospital.

“Our plan is to make sure we have sufficient numbers of specialists, nurses, therapists, staff and volunteers…to provide that level of enhanced care,” explained Rolls. “It’s still a home and the whole focus is around the veterans as we downsize.”

The Legion is watching carefully, said Jean Marie Deveaux, past president of Nova Scotia/Nunavut Command of The Royal Canadian Legion. “We have someone there every week to attend the veterans’ council meeting, and people there visiting every day.” Deveaux worries about veterans being stressed by moving rooms and closing of units. “Some have lived in the same room on the same floor for years; to them it’s home.”

The veterans’ units will close one by one as the veteran population declines. As of last fall it had not been decided what would fill the space, but the Camp Hill Veterans’ Memorial Building is part of the Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, which has hospital, mental health, rehabilitation and research facilities.

The end will be emotional. Camp Hill Hospital, named for a military camp dating back to 1757, began serving First World War casualties in 1917; long-term care began in 1924. Its many volunteers and community partners include Legion branches, the Chief and Petty Officers’ Association, as well as members of the serving military. Veterans Affairs Canada’s annual funding for veterans’ care, $23 million in 2012, partially funds many staff positions in the health region.

![Second World War veterans Noel Gooding and Betty Jevne. [PHOTO: SHARON ADAMS]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/access3.jpg)

The community, the Legion and the military have raised funds for such enhancements as the veterans’ garden, and it’s a shame for these things not to be enjoyed by veterans, “especially since there are modern-day veterans who could go there,” said Deveaux.

The George Derby Centre in Burnaby, B.C., also has a long history. It was named after a disabled First World War veteran, an early Veterans Affairs employee, who helped write the first Veterans Charter and negotiated land for the original centre in 1946.

The heart of the new building, which opened in 1988, is a glass-canopied town centre, its ‘streets’ dotted with benches and lined with gift shop, canteen, banking services, dental office, library, hair salon, chapel, art studio and music room. Every room in the four living areas and dementia unit has a spectacular view of lush West Coast greenery.

The George Derby Centre has already begun its transition to a community facility. “We have 300 residents; about 225 are veterans,” explained Mel Elliott, acting executive director. Priority access beds unclaimed by veterans go to civilians only when there are ongoing vacancies and no wait list, states VAC.

On a rainy Tuesday, the town centre is busy with groups playing billiards, cards and chess. Second World War tunes are the sound track as Betty Jevne, who came to the centre in 2012 after breaking a hip, chats in the art studio with five-year resident Noel Gooding who landed on Juno Beach on D-Day. “We don’t get to talk about our war experiences,” said Gooding. “Not very often, anyway.”

“This is the only place to be if you’re a veteran,” added Jevne, 90, who signed up with the Women’s Division of the Royal Canadian Air Force on her 18th birthday in 1942. She uses a motorized wheelchair to get around, but she’s still a party girl at heart. She and her husband travelled in a motor home for 20 years. “We met people and drank and danced and had a good time.” Her only complaint now is that the streets roll up too early. “I do like to be out late.”

![The George Derby Centre is bathed in light, even on a cloudy day. [PHOTO: SHARON ADAMS]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/access4.jpg)

The programs offered at George Derby keep her hopping, Jevne added. But those programs may not survive after the traditional veterans are gone and there is no more VAC funding. Though Elliott was reluctant to discuss finances, John Scott, chairman of the Veterans Service and Seniors Committee for the Legion’s British Columbia/Yukon Command, said withdrawal of VAC funding is hurting all the province’s long-term care facilities that house veterans. For some, it’s meant hundreds of thousands of dollars of funding has evaporated, threatening enhanced care and programs like art and music therapy, which are open to all residents, not just veterans.

The George Derby is working hard to find alternate funding, explained Elliott, and is working with Simon Fraser Health Authority and VAC to ensure a smooth transition from veteran-based to community-based facility. To ensure its long-term future, the centre plans to meet wider needs of the growing seniors community and is investigating building assisted living seniors apartments.

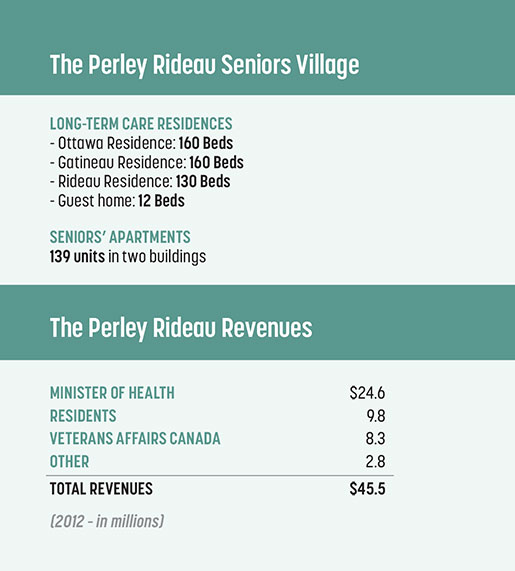

In Ottawa, the Perley and Rideau Veterans’ Health Centre is a little further along with both strategies. It is about a third of the way through a 15-year plan to create a Seniors Village. This plan will see it through dwindling VAC financial support, help the province meet its challenge to provide for an aging population and keep its commitment to honour veterans and maintain its veterans’ culture.

The Perley will provide a continuum of seniors’ care, including a 450-bed long-term care facility (which now has 250 priority access beds), an adult day program; respite, convalescent and dementia care; 139 independent apartments; and assisted living services. Village amenities include a drug store, barber shop and salon, banking, fitness centre, art studio, recreational activities, gardens and green spaces. Now in planning is a primary health clinic and wellness centre. Commercial, health and recreation facilities will be open to seniors and veterans in the surrounding community.

“We made a decision that our long-term future would be tied to veterans,” said Akos Hoffer, the centre’s chief operating officer. Canadian Armed Forces members—anyone who’s honourably served at any time—have priority access to up to 30 per cent of the apartments.

The centre has reached out to the Perley and Rideau Veterans’ Health Centre Foundation to fund $5 million of the $42.3 million building project; $1.5 million has been raised so far, said Daniel Clapin, the foundation’s executive director. Programs do not rely solely on VAC funding and the centre is seeking additional donors to make up for waning VAC financial support.

The creative arts and recreation program is vital to residents’ quality of life, said Carolyn Vollicks, manager of programming and support. “There are a lot of losses in the lives of people coming here.” Art, music or gardening often gives residents a new lease on life.

The province will still control the long-term care waiting list, but the Perley is creating an opportunity for what Hoffer calls a ‘warm transition.’ “We will know very early on when a tenant should get on the long-term waiting list. The last thing you want when you’re 90 years old is to relocate to a new environment.”

The Perley village concept attracted veterans Norma and Jack Watts, who are among the first apartment residents, as they considered options for their long-term future. “If one or both of us begins to deteriorate, well, it can be handled,” said Jack. “We can both be looked after and it can be in the same place.”

They met and married in England in 1944, when Jack was flying with Bomber Command and Norma was in airfield operations. Jack spent 34 years in the Royal Canadian Air Force before they retired to Kemptville, Ont., where eventually household and gardening became onerous.

With a little help, they can still look after themselves. The Veterans Independence Program takes care of housekeeping; they mostly make their own breakfast and lunch, but go to the communal dining room for dinner. Should they eventually need more help, they can tap into other support services, including health and medication monitoring.

With assistive living services, the Watts may never need long-term care. But if they do, it’s a comfort to these traditional veterans to know they will have priority access.

It’s a different story for veterans who served after the Korean War. They now make up just over five per cent of the 8,500 veterans supported by VAC in 1,700 long-term care facilities across Canada, at a cost of $266 million in 2011-2012. Even when they qualify for financial support by VAC, modern veterans must first meet criteria for long-term care in their provincial health care system. Then they queue up with civilians for assignment to a facility, which may not be the one they prefer and may not have other veterans as residents.

Should priority access to long-term care beds be provided to modern veterans? Should more thought go into grouping veterans together in long-term care facilities? These and other questions will be tackled in the second part of this story, which will appear in the July/August issue.

Advertisement