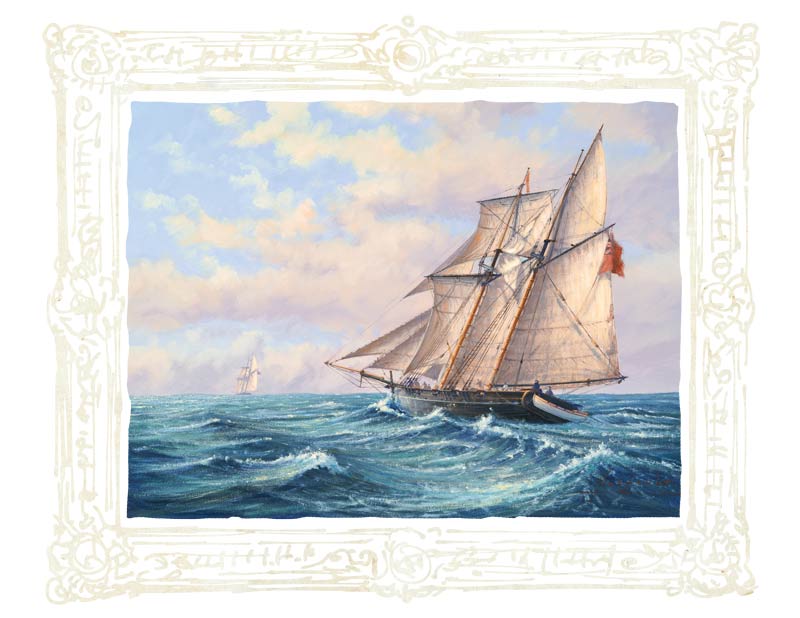

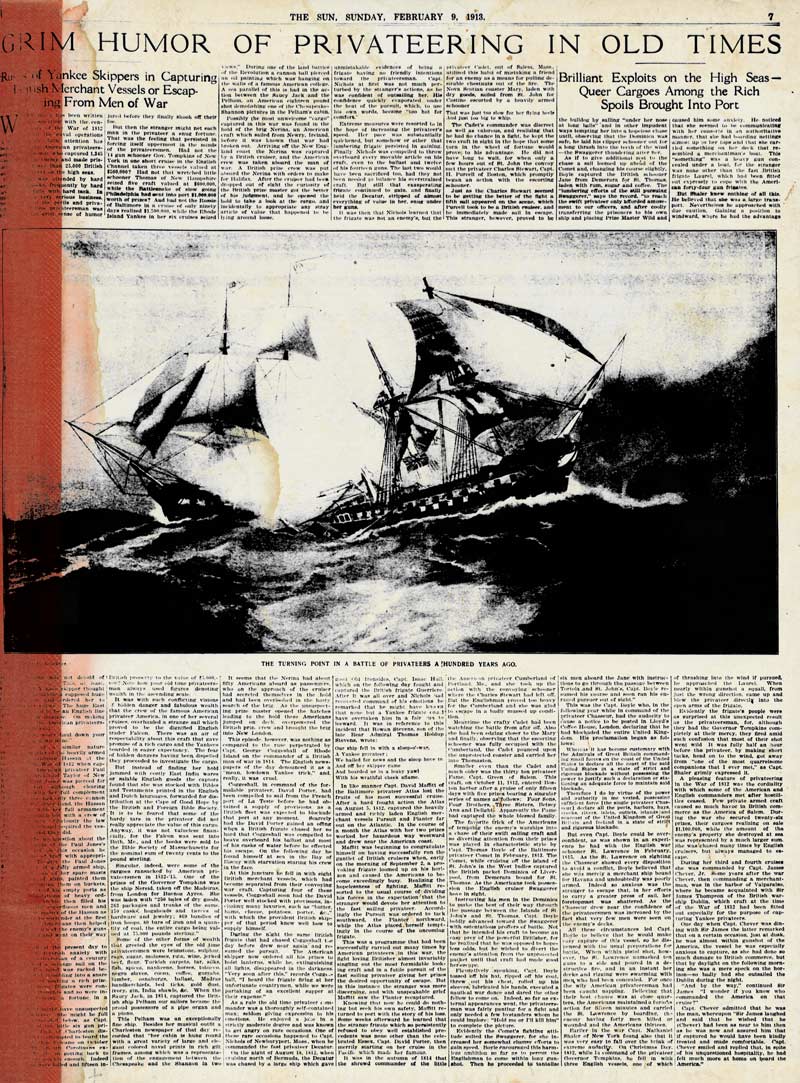

“Stern Chase” by artist John M. Horton depicts the privateer ship Liverpool Packet chasing a quarry off Massachusetts during the War of 1812. [John M. Horton]

It may have been the best investment Enos Collins, Benjamin Knaut and John and James Barss ever made.

In 1811, the merchants of Liverpool, N.S., purchased Severn, a former tender to a Spanish slaver captured by the Royal Navy, for a few hundred British pounds (tens of thousands of dollars today). Lucky for them, war broke out with the United States a few months later, and the boys were in business, big-time.

Enos Collins, Packet’s principal owner, was rumoured to be the richest man in Canada when he died in 1871. [Notman Studio Collection/Nova Scotia Archives]

They renamed the Baltimore clipper-style schooner Liverpool Packet, and initially ran mail between their hometown and Halifax.

With the outbreak of the War of 1812, however, they acquired a letter of marque from the king of England and embarked on the most successful privateering spree mounted by any of the 40-odd Canadians licensed as maritime mercenaries during the conflict.

God damn them all, I was told We’d cruise the seas for American gold. We’d fire no guns, shed no tears Now I’m a broken man on a Halifax pier The last of Barrett’s privateers

—“Barrett’s Privateers,” by Stan Rogers

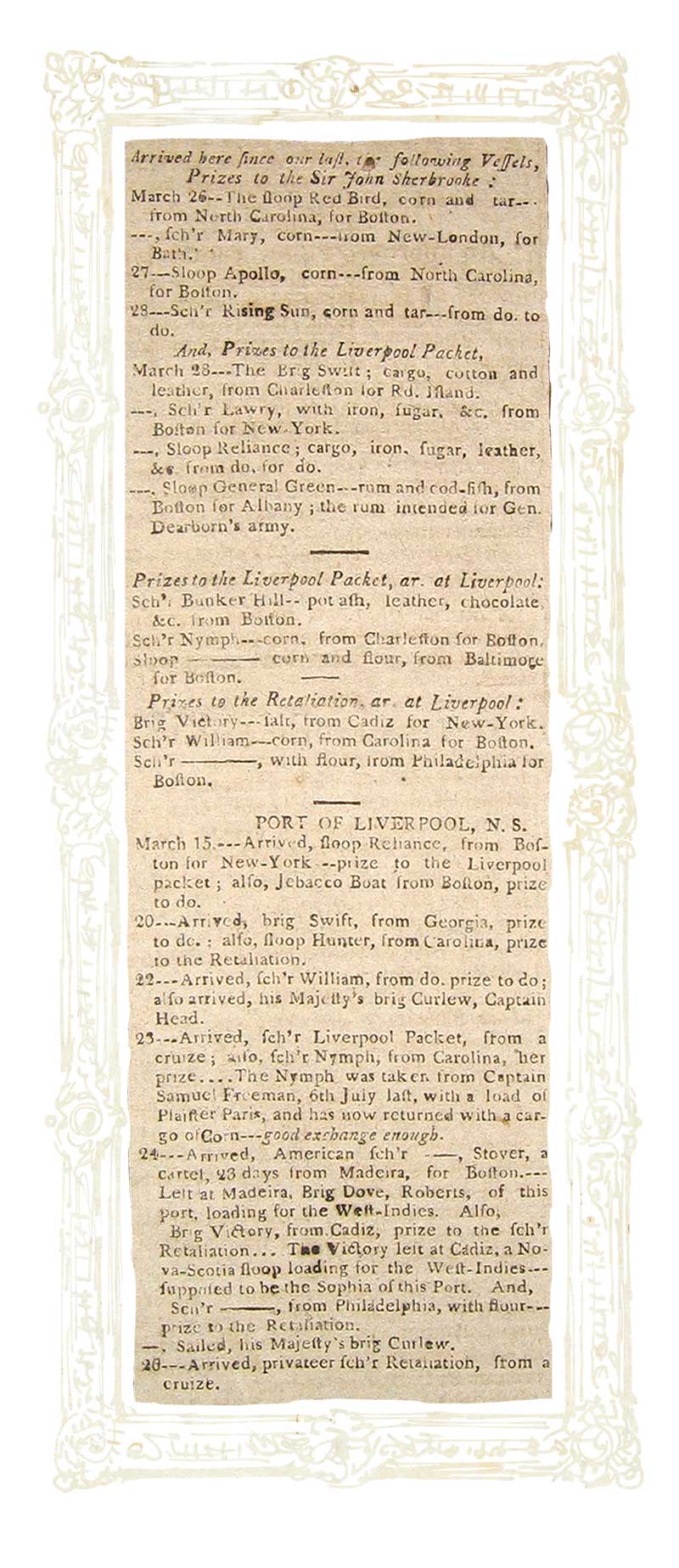

One of the ship’s letters of marque—its licence to plunder.[Nova Scotia Historical Society/Nova Scotia Archives]

Liverpool, with its sheltered harbour on the province’s South Shore and boundless access to the region’s rich sailing stock, was considered the privateering capital of British North America at the time and the speedy, upstart Packet, with its five guns and 45 crew, proved a formidable presence along the New England coast.

During its war-long spree, the ship captured some 50 American vessels and their cargoes, then worth between $262,000 and $1 million (equivalent to the 2023 purchasing power of C$4.8M-$18.6M).

Classic naval engagements such as the Battle of Lake Erie and the clash between HMS Shannon and USS Chesapeake, which ended with a captured Chesapeake paraded up Halifax Harbour, earned much of historians’ attention. But skirmishes between what were at their core small, souped-up cargo and fishing vessels were a continuing feature of the last great conflict between the U.S. and Britain.

Colonial privateers had played a key role in the 1775-1783 War of Independence, capturing hundreds of British vessels and seizing coveted muskets and gunpowder for the Continental Army.

During the War of 1812, it’s estimated that American privateers captured millions in British commerce, much of it off the British Isles. By 1814, British maritime insurance firms were routinely charging a whopping 13 per cent on shipments between England and Ireland. The Naval Chronicle reported that was triple what it was when Britain was at war with “all of Europe.”

HMS Shannon escorts its war prize, USS Chesapeake, up Halifax Harbour on June 1, 1813.[J.C. Schetky/Day & Haghe Lithographers/CWM/20180033-005]

The British monarch and his representatives issued some 3,000 letters of marque during the Napoleonic Wars, which included the period 1812 through 1815.

The documents—licences to plunder—represented gains for everyone involved, save the hapless victims. They essentially legitimized the practice of piracy against an enemy country’s sea-going vessels, no matter how innocent they might be. By seizing and looting merchant ships, fishing boats, whalers and others, privateers interfered with commerce, disrupted supply, distracted naval resources and, in some cases, made themselves fortunes.

The golden age of piracy was long over. Names such as Blackbeard, Calico Jack, Henry Morgan and Samuel (Black Sam) Bellamy had become the stuff of legend, their long-lost treasures lying at the bottom of the Caribbean or buried, perhaps, beneath Nova Scotia’s Oak Island.

A century after the Jolly Roger terrorized seafarers around the world, the needs and desires of the English king had bestowed a measure of legitimacy on the practice, and opportunists were more than willing to cash in.

“The privateers of Nova Scotia played an integral role in closing American ports during the War of 1812,” wrote James H. Harsh in The Canadian Encyclopedia. “They were a valuable source of intelligence for the Royal Navy on American strength and ship movements.”

For the privateers, however, the benefits were less certain.

Their handpicked crews were made up mostly of volunteer fishermen with dreams of fame and fortune. None was offered wages; their rewards were to be shares in the prizes they captured.

Yet 15 of the 40-some commissioned privateering ships from New Brunswick and Nova Scotia failed to capture a single prize; another 10 took just one each. The rest made fortunes for their owners.

And none more than Liverpool Packet.

The 53-footer (16-metre) was at anchor in Halifax Harbour on June 27, 1812, when the British frigate Belvidera arrived in port bearing news of the American declaration of war with England nine days earlier. The ship had on board 17 casualties from a day-long fight with five American ships.

Packet’s crew hastily loaded five rusty cannons aboard their vessel and made for Liverpool to await Britain’s response to the American challenge—and an anticipated letter of marque. By mid July, the Nova Scotia coast was swarming with American privateers, who were capturing merchantmen almost daily.

Packet would acquire its licence to raid and captured at least 33 American ships in the war’s first year. The ship, first commanded by an aging John Freeman—a privateering veteran of the French and Spanish wars—and later a younger but seasoned mariner, Joseph Barss Jr., would lie in wait near Cape Cod, Mass., attacking U.S. vessels headed to Boston and New York.

“All awake!” trumpeted Boston’s Columbian Centinel newspaper on Dec. 19, 1812. “The Liverpool Packet has again raided our coast.” The privateer returned to Liverpool two days later with a pair of prizes in its wake.

Enemy ships weren’t the only perils Packet faced. A storm that month forced Barss to take the ship out into the open ocean where he could ride it out. “At midnight tremendious Gails and Sea on,” noted a logbook, “the seas breaking over the vessel from Stem to Stearn.”

The Nova Scotia Royal Gazette of March 31, 1813, reports the prizes taken in recent months by privateers Sir John Sherbrooke and Liverpool Packet.[Thomas Hayhurst/Queen’s County Museum]

But the rewards proved astounding.

A list of prizes published in the Nova Scotia Royal Gazette on March 31, 1813, includes four taken on March 28 alone: the brig Swift, captured while en route from Charleston, S.C., to Rhode Island with a load of cotton and leather; the schooner Lawry with a load of sugar, iron and cotton bound for New York from Boston; and the sloop Reliance, headed for an undetermined destination with iron, sugar, leather and cotton. It also captured the sloop General Green, destined for Albany, N.Y., from Boston with codfish and rum for the army of General Henry Dearborn.

Other prizes taken by Packet were anchored at Liverpool, including the schooner Bunker Hill loaded with chocolate.

Packet’s owners were so inspired by the ship’s success they bought the brig Sir John Sherbrooke, formerly the American privateer Thorn. With a displacement of 273 tons, the warship had 18 guns and was crewed by 150 men. It has been said that it achieved the fastest success of any Canadian privateer, but estimates of its prizes vary widely.

Its notoriety spread far and wide, Packet earned the nicknames New England’s Bane and The Black Joke, a moniker borne by several infamous slave ships.

Packet was a veteran privateer by the spring of 1813 and three months out of port when its run of good luck took a turn: it came upon the American privateer Thomas out of Portsmouth, N.H.—twice Packet’s size, wielding 15 guns with a crew of 100.

The five-hour chase began in light winds at 9 a.m. on June 9. Packet’s crew dumped all but one of the ship’s short-range guns overboard to lighten their load, and moved their one remaining six-pounder to the stern. As their pursuer closed, they fed the cannon with six-pound shot, then tried a four-pound ball wrapped in canvas. It split the muzzle.

“At 2 p.m., coming up with the chase very fast, the schooner hoisted her colours and commenced firing her stern chasers,” Liverpool historian George E.E. Nichols related in a 1904 presentation entitled “Notes on Nova Scotian Privateers.”

“Overtaken by the American, she rounded to, struck her colours and ran alongside the Thomas. In the act of veering, she fouled the Thomas, and thinking their opponents about to board their vessel, the respective crews engaged in a hand to hand encounter.

During its war-long spree, the ship captured some 50 American vessels and their cargoes.

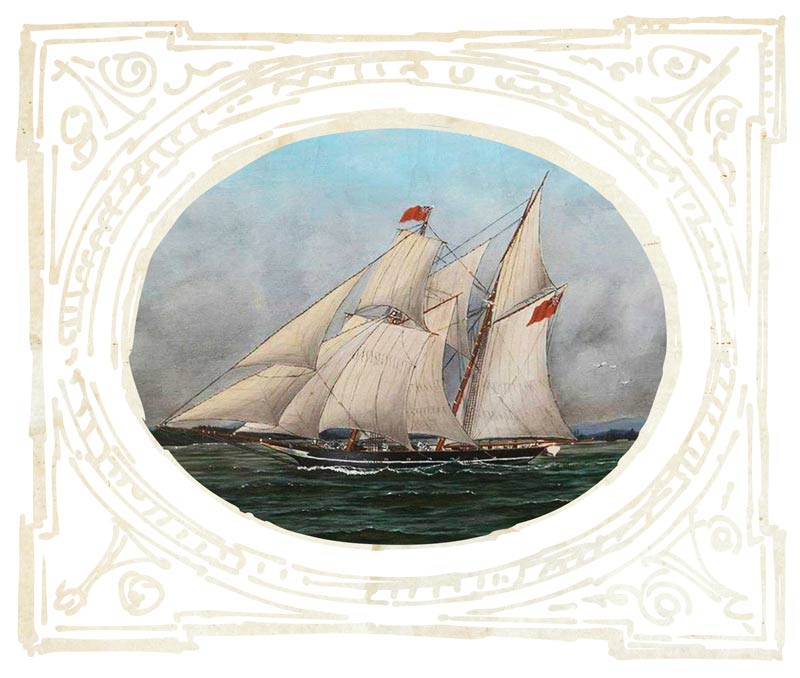

Thomas Hayhurst depicts Packet in full sail. The Nova Scotia Royal Gazette of March 31, 1813, reports the prizes taken in recent months by privateers Sir John Sherbrooke and Liverpool Packet. [Thomas Hayhurst/Queen’s County Museum]

“After striking her colours, the officers and crew of the Thomas repeatedly fired into the Liverpool Packet and threatened to give her crew no quarter. Greatly outnumbered, they were compelled to surrender, but not before several of the crew of the Thomas had been killed.”

Three weeks later, the American ship was taken by a British frigate after a 32-hour chase. It was brought to Halifax and sold to Liverpool privateers, the largest shareholder among them Barss’ father, Joseph Sr., a Queen’s County representative in the House of Assembly.

The Thomas of Portsmouth became the Wolverine of Liverpool. It took eight prizes before the year was out.

Meanwhile, Joseph Jr. was taken to Portsmouth, where he was kept under armed guard for several months before John Coape Sherbrooke, lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia, a former British army general and namesake of the aforementioned privateer, secured his release.

Liverpool Packet was converted to an American privateer and eventually renamed Portsmouth Packet. But in October 1813, HMS Fantome, an 18-gun brig-sloop, encountered the schooner off Mount Desert Island, Maine.

A chase ensued, lasting 13 hours before Fantome seized its quarry and brought the prize to Halifax. Packet was repurchased by its former owners, its Liverpool name restored. It resumed its plundering under the command of Caleb Seely.

Packet’s second letter of marque is now held in the Nova Scotia Archives.

Dated Nov. 19, 1813, it authorized Seely and his ship “to apprehend, seize and take, the Ships, Vessels and Goods, belonging to the United States of America, or to any persons being citizens of, or inhabiting within, any territories of the United States of America…according to His Majesty’s Commission.”

As part of his privateering duties, Seely was ordered to take note of “the situation, motion, and strength of the Americans, as well as he can discover by the best intelligence he can get.”

Packet closed the year with three more prize vessels to its credit.

The ship had a successful 1814, too, capturing prizes in May and June, then taking two more alongside Shannon near New York and Bridgeport, Conn. Packet worked often with British naval vessels through the end of the war.

Barss was appointed skipper of his former captor, Wolverine, in 1814 and sailed as a trader to the West Indies. The Americans considered his mere presence on the high seas a violation of his parole, however, and his seafaring days ended on his return to Liverpool in August.

American privateers continued their campaign off the Americas, their commissions issued on a per-voyage basis by the Continental Congress and state governments.

Working out of ports like Savannah, Ga.; Elizabeth City, N.C.; and Mobile, Ala., skippers such as John Peter Chazel, Hugh Campbell and Herman Perry sailed fast schooners and brigs along the continent’s east coast raiding merchant vessels.

American privateers didn’t limit their prey to British merchants, either. Records show they also captured Swedish, Spanish, Portuguese and Russian ships.

Believed to be the most successful of the Americans was a six-gun schooner dubbed Saucy Jack, owned by Charleston, N.C., merchant John Everingham. On its maiden voyage, Saucy Jack, captained by Thomas Jervey, took the brig William Rathbone, along with its 14 guns and a cargo worth about C$7M today. Though the British ship, known as a West Indianman, was later recaptured, the incident was a harbinger for the American’s successes under three different captains.

The log of Saucy Jack’s last and most successful privateer skipper, Chazal, tells of a bloody encounter with the 540-ton, 10-gun British trader Pelham between Cuba and Santo Domingo on April 30, 1814.

“In the act of boarding, Stephen Dunham, one of our seamen, was shot dead and our First Lieutenant, Dale Carr, mortally wounded while fighting on the enemy’s deck,” Chazal wrote. “At the same time our second Lieutenant Lewis Jantzen and John St. Amand, Lieutenant of Marines, was severely wounded, together with 7 of our men. Making our loss 2 killed and nine wounded, 8 of which badly.

“On board the Pelham there were 4 killed and 11 wounded; among the latter, the Captain and his Chief Mate (since died).”

The Feb. 9, 1913, edition of The New York Sun commemorates the privateers of a century before. [Nova Scotia Archives]

With hostilities over and privateering all but ended by the Treaty of Ghent and shifting Royal Navy policy, ship owners from both sides, including Everingham, tended to go back to what they knew best, merchant trading.

Privateers who continued raiding after their commission expired or a peace treaty was signed could face piracy charges. The penalties were harsh—convicts were hanged at the beach in Halifax, then tarred and hung in chains (gibbetted) at the harbour entrance as a warning to other mariners.

Thus, combined with an expanding naval role on the high seas, privateering all but disappeared by the end of the 19th century.

“The Liverpool privateersmen were of excellent stock, all leading citizens of the community, well and favorably known to British naval officers of the time,” Janet E. Mullins wrote in The Dalhousie Review. “When the wars were over, many filled positions of honour as members of parliament, judges, ship-owners, merchants.”

Packet’s owners sold their feisty little ship in Kingston, Jamaica. Its fate beyond that is unknown. Several ships have since carried its name.

The vessel’s success helped launch the great fortune of its principal owner, Enos Collins, who would go on to co-found the Halifax Banking Company, which merged with the Canadian Bank of Commerce in 1903.

Born to a merchant family in Liverpool, he had sailed on a few privateering escapades to the West Indies in his youth. He was rumoured to be the richest man in Canada when he died in 1871 at the age of 97.

Making their marque

In 1904, Liverpool, N.S., native and passionate amateur historian George E.E. Nichols gave a presentation entitled “Notes on Nova Scotian Privateers,” which included a strident defence of the practice that, by some, was considered immoral.

George E.E. Nichols’ 1904 “Notes on Nova Scotian Privateers” sought to clarify the history and correct some negative interpretations of the trade.[Nova Scotia Archives]

Private vessels of war, he noted, operated under strict regulations set down by the Crown. None could go on a prize-hunting cruise without first obtaining a licence, known as a letter of marque.

To obtain one, a ship’s owners had to meet a series of requirements and undertakings:

- Their vessel’s tonnage, armament, ammunition, etc., together with the names of the owners, officers and men were to be registered with the Admiralty Court—in Nova Scotia’s case, in Halifax;

- A regular account of captures and proceedings had to be kept in a logbook and any potentially valuable information obtained about the enemy reported;

- no one taken or surprised in any vessel, though known to be of the enemy, were to be killed in cold blood, tortured, maimed or inhumanely treated “contrary to the common usages of war.” Prisoners were not to be ransomed;

- privateers were not permitted, under peril, to fly any colours usually shown by the king’s ships. They were required to fly a Red Ensign;

- bail with sureties (guarantors) was required either on behalf of the owners, if residents, or the captain. The amount varied according to the number of crew. If they exceeded 150 men, 3,000 pounds sterling [about C$500,000 today] was required, while fewer than 150 demanded half the cost.

Prizes were to be taken to the most convenient port in the dominions of the Crown, where they would be adjudicated upon by the Court of Admiralty. Once declared a legitimate seizure, the captors were permitted to sell the vessel and its cargo in an open market “to their best advantage.” The proceeds were typically distributed by percentage between the privateers’ sponsors, shipowners, captains and crew. And a share usually went to the issuer of the commission (the Crown).

Advertisement