Survivors of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp collect bread rations from a cookhouse after the liberation in April 1945. [IWM BU-4274]

What they witnessed there in northern Germany was unimaginable: 13,000 emaciated corpses lying in heaps throughout the camp among about 60,000 starving and sick inmates, mostly Jewish; about 500 were children. Teen-aged diarist Anne Frank died there of typhus, just weeks before the camp was liberated.

On the heels of the British came a Canadian battalion, some of the more than 1,000 Canadians involved in liberating Nazi concentration and extermination camps throughout Germany.

The battalion included medical staff—doctors, nurses, nutritionists. But over the next month about 14,000 more inmates died, too far gone from typhus, cholera, dysentery and starvation to be nursed back to life.

Jack Markovitch of Montreal helped arrest the camp commandant, Josef Kramer, who was later sentenced to death. During the liberation of the Vught concentration camp in the Netherlands, says Ellin Bessner in Double Threat: Canadian Jews, the Military and WW II, Markovitch found a prayer book of a murdered Dutch family, which he kept the rest of his life.

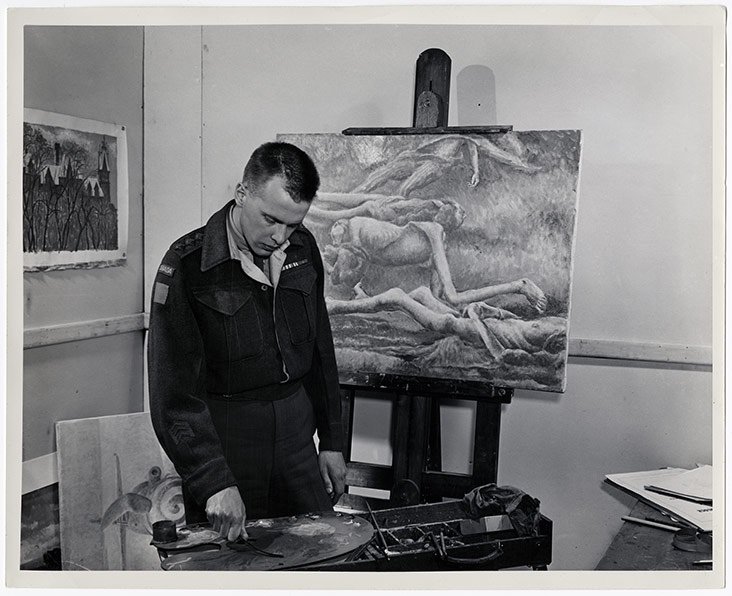

Alex Colville was one of three Canadian war artists who entered the German concentration camp of Bergen-Belsen after its liberation by British forces. Here he stands in front of his painting “Bodies in a Grave, Belsen.” [COLVILLE COLLECTION/CWM]

A short time later, combat pilot Brian MacConnell’s squadron, stationed nearby, was taken to the camp. “I’m pretty sure we were taken there to tell people what we had seen. We were in complete shock. I couldn’t believe a civilized country like Germany could do such a thing.” RCAF reconnaissance photographer Moe Resin gave chocolates to female survivors.

Sol Goldberg, who worked in a mobile shower and laundry unit, became frustrated with the pace of relief efforts and went around the bureaucracy to speed things up, according to an article by his son David in The Canadian Jewish News. Aside from Canadian supplies he liberated, word was sent among soldiers and airmen in the region, and soon blankets, clothing, boots and food were flowing in to him. He cut a hole in the camp’s fences and smuggled supplies directly to survivors, who trusted him because he spoke fluent Yiddish.

Goldberg was caught once, but instead of pursuing disciplinary measures, his commanding officers abetted his efforts, giving him additional supplies.

Advertisement