“A horse must be a bit mad to be a good cavalry mount, and its rider must be completely so.” ―Steven Pressfield, The Virtues of War

Izbushensky is a hamlet in the west Russian oblast of Volgograd, roughly on the same latitude as Lethbridge, Alta. Its population in 2010 was just 14 people.

If you look for pictures of Izbushensky via Google, you won’t find golden waves of wheat blowing in the wind, thatched-roofed dachas or quaint old Russian ladies wrapped in babushkas.

No, find Izbushensky and you’ll find horses.

It was here, sometime after 3:30 a.m., on Aug. 24, 1942, near the junction of the Don and Khopyor rivers, that Italy’s Savoia Cavalleria drew their sabres and launched what some consider history’s last major cavalry charge.

Italy’s Savoia Cavalleria launch what some consider history’s last major cavalry charge, near the west Russian hamlet of Izbushensky.[Unknown]

Founded in 1692, the Italian regiment’s original recruiting area was the Duchy of Savoy. Hence, their battle cry: “Savoia!”

Among other conflicts, the Savoias had fought in the Nine Years’ War (1688-1697), the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1714), the First Italian War of Independence (1848-1849) and the First World War.

Now, they faced machine guns, armoured tanks, mobile artillery and a host of other technological advances that were supposed to have rendered horse cavalry obsolete.

Germany and the Soviet Union employed more than six million horses between them in the years 1939-1945.

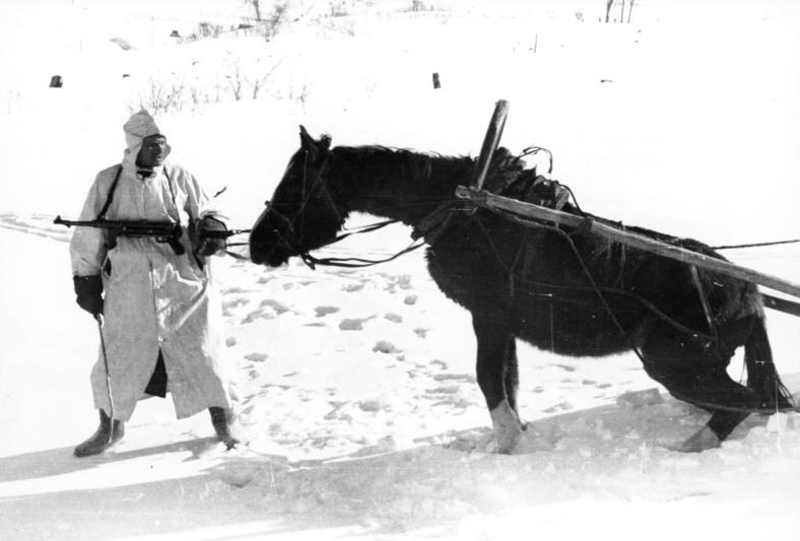

A German soldier and his horse struggle on the Russian steppe in 1941. In two months—December 1941 and January 1942—the Wehrmacht lost 179,000 horses on the Eastern Front. [Bundesarchiv Bild/101I-215-0366-03A]

Canada’s last great cavalry charge took place at Moreuil Wood in France on March 30, 1918. Nearly three-quarters of the Canadians involved in the attack against German machine-gun positions were killed or wounded.

The dead included Lieutenant Gordon M. Flowerdew of the Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians), who was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross after leading the charge.

The cavalry, however, remained behind the lines for much of The Great War, unable to break the trench deadlock and of little use at the front. During the German offensives of March and April 1918, it played an essential role in the open warfare that temporarily confronted retreating British forces.

But in the military especially, traditions die hard. And, for some—1940s Germany, in particular—impossible production demands and shortages of domestic oil supply necessitated the use of horses. As a result, Germany and the Soviet Union employed more than six million horses between them from 1939-1945.

The bulk of the Wehrmacht, in fact, was made up of infantry and horse-drawn artillery, while mobile panzer and mechanized divisions incorporated just a fifth of German troops.

Each German infantry division employed thousands of horses and men to care for them. Animals were lost to battle wounds, exposure and disease, yet Germany maintained a steady supply of work and saddle horses until 1945.

Much of the Red Army was motorized before 1941, but most of its equipment was lost during the German invasion of June 1941. Mounted infantry filled the gaps and were used as strike forces in the Battle of Moscow.

Heavy casualties and a shortage of horses soon forced the Soviets to reduce their number of cavalry divisions. As tank production and Allied supplies, delivered via the notorious Murmansk convoy run from Halifax and other North American ports, caught up with the losses of 1941, cavalry merged with tank units.

But the starving U.S. and Filipino soldiers resorted to eating their own horses and ultimately surrendered.

The use of war horses was largely influenced by national economies and industrial production and supply. In some countries, shortages of motorized vehicles and the hydrocarbons to operate them boosted reliance on horses, while declines in horse stocks elsewhere spawned programs to replace them with powered vehicles.

The British started replacing horse cavalry with motorized troops in 1928. By 1939, they had a motorized national army. Still, it wasn’t until the Battle of France that senior officers of the traditional services embraced the concept.

The French partially motorized their cavalry in 1928, creating divisions of dragons portés (mobile dragoons) that combined motorized and horse-mounted elements. For the next decade, they sought the optimum blend of the two.

Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania followed the French lead; Austrian and Czechoslovak mobile divisions maintained a higher proportion of horses. Though the Polish army acquired tanks and the Lithuanians got trucks, both remained primarily horse-powered, First World War-style armies.

U.S. cavalry commanders approved adoption of the French configuration, but made no radical changes until a 1940 reform largely eliminated horse-borne soldiers. Still, American forces fielded a few cavalry and mounted supply units.

On Jan. 16, 1942, mostly Filipino troopers of ‘G’ Troop, 26th Cavalry (PS) led by U.S. First-Lieutenant Edwin Ramsey, launched what would be the last horse cavalry charge in American army history, at Morong in Bataan.

The lightly armed, 27-man force successfully charged a superior Japanese force of armour-supported infantry, surprising and scattering them. Then, under heavy fire, they held off the Japanese for several crucial hours.

But the starving U.S. and Filipino soldiers resorted to eating their own horses and ultimately surrendered. Two months later, Japanese troops in Burma wiped out a charging Indian regiment under British command.

General George S. Patton lamented the absence of the horse in North Africa and Italy, writing that “had we possessed an American cavalry division with pack artillery in Tunisia and in Sicily, not a German would have escaped.”

China, Japan and Mongolia all maintained significant cavalry elements during the Second World War.

Some bullet-riddled horses galloped on for hundreds of metres, spouting blood at every beat before collapsing and dying before they hit the ground.

The action at Izbushensky began spontaneously when an Italian mounted patrol, sent to recon the objective, encountered Soviet troops. The Soviets opened up on the whole Italian line, leaving the Italian commander, Count Bettoni Cazzago Alessandro, no choice but to order a cavalry charge on entrenched infantry.

More than 100 horsemen of the 2nd Squadron stormed the left flank of the Soviet line longitudinally, wielding sabres and hand grenades.

Some bullet-riddled horses galloped on for hundreds of metres, spouting blood at every beat before collapsing and dying before they hit the ground. Half the riders were killed or wounded before they reached halfway down the Soviet line.

The 4th Squadron was ordered to dismount and launch a frontal attack after the Italian commanders realized that, while the 2nd had taken heavy casualties, it was about to suffer considerably more. The lead element had jumped the foxholes of the Soviet troops, who were now rising to shoot them in the back.

The 4th’s following attack allowed the 2nd to regroup and charge back, dislodging the Soviets from their positions. The 3rd Squadron then mounted a full-frontal attack. What was left of the 2nd—a dozen horsemen—joined them.

The action was over by 9:30 a.m., six hours after it had begun. Some 32 Savoias were dead, another 52 wounded, with the loss of more than 100 horses. The Soviets suffered 150 dead, 300 wounded and 600 captured, and lost cannons, mortars and 50 machine guns.

“Scotland Forever!” is an 1881 painting by Lady Butler depicting the start of the cavalry charge of the Royal Scots Greys who charged alongside the British heavy cavalry at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 during the Napoleonic Wars. [Elizabeth Thompson/Wikimedia]

The Polish commander, Colonel Kazimierz Tadeusz Majewski, ordered his men to ride straight into the enemy ranks.

There were other cavalry battles during the war, mostly in Eastern Europe.

Polish lancers played a key role in their country’s defence at the outset of hostilities, frequently prevailing in battle, breaking up German infantry formations, liberating towns and overrunning fortified positions.

In a fabled 1939 encounter at the northern Polish town of Chojnice, elements of the Polish 18th Lancers surprised a body of troops from the German 20th Motorized Infantry Division. The Polish commander, Colonel Kazimierz Tadeusz Majewski, ordered his men to ride straight into the enemy ranks.

The Germans broke and fled.

German armoured cars counterattacked and forced the Poles back but, contrary to a myth that persisted for decades, it was hardly a mass slaughter. The lancers lost roughly 20 of their 250 men.

After the battle, foreign journalists surveyed the site and noted the dead horses and cavalrymen, along with some tanks that had arrived after the action. Reports emerged that horsemen wielding swords and lances had gone up against panzers.

In 2009, The Guardian newspaper issued a correction after it printed an anniversary piece about the invasion of Poland characterizing the Polish lancer charge as “the most romantic and idiotic act of suicide of modern war.”

“The story feeds a stereotype about Polish men being hopelessly romantic, hopelessly mustachioed idiots who would actually gallop their horses at big steel tanks,” Julian Borger wrote for the newspaper two years later.

By the time the war ended in 1945, it had taken the lives of between two million and five million horses.

At the time, the Nazi propaganda machine and its Soviet counterpart used the story to portray Polish officers—whom Stalin executed en masse the next year—as absurdly careless about the lives of their troops.

“What is most irritating to Poles about this particular fable is that it trivialises the Polish contribution to the allied war effort, reducing it to a single moment of whimsy,” said Borger, citing characterizations of the Polish role in the war’s outcome as “extraordinary, perhaps even decisive.”

Some major cavalry actions even postdated what would become known as “The Charge of the Savoia Cavalleria,” raising the question of when significant cavalry action actually ended.

At the March 1945 Battle of Schoenfeld in northwestern Poland, the 1st “Warsaw” Independent Cavalry Brigade mounted what has been described as “the last mounted charge in the history of the Polish cavalry and the last confirmed successful cavalry charge in world history.”

The cavalrymen overran the German anti-tank gun positions and then, supported by infantry and tanks, took the town itself with relatively minimal losses—147 killed to the Germans’ 500 or so.

By the time the war ended in 1945, it had taken the lives of between two million and five million horses—there is no official figure, but the numbers are a fraction of the eight million killed in The Great War.

Horses would continue to be used, primarily as beasts of burden, to a far lesser extent in conflicts all over the world, but the “glory” days of cavalry had passed.

Advertisement