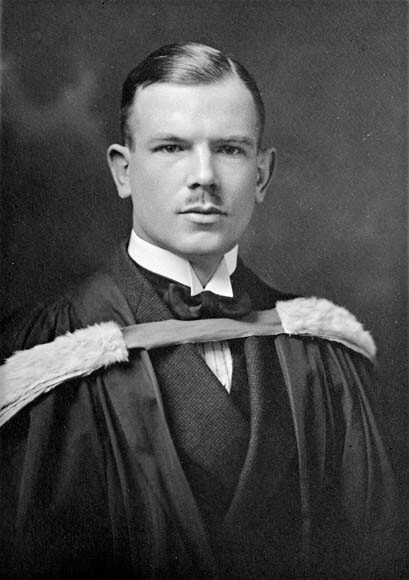

Henry Norman Bethune during his medical school graduation in 1916. [Wikimedia]

The Gravenhurst, Ont., native, whose grandfather had himself been a surgeon during the Crimean War, first volunteered for the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps in September 1914, serving as a stretcher bearer on the Western Front.

Bethune, then aged 25, was wounded during the 1915 Second Battle of Ypres. He subsequently returned home, completed a previously deferred medical degree, and re-enlisted in the Royal Navy before transferring to the Canadian Flying Corps.

His surgical aspirations continued after the Great War, although they suffered a setback when Bethune contracted tuberculosis in the mid-1920s; his experience combating TB ultimately inspired him to help others living with the disease.

But eradicating tuberculosis wasn’t the only cause close to his heart.

With the 1930s Great Depression inflicting poverty on the vulnerable, Bethune turned his attention to the cause of socialized medicine in Canada. The impassioned doctor, long considered an eccentric, opened a free clinic for the unemployed, joined the Communist Party, and visited the Soviet Union.

When Spain’s nationalist rebels attempted to overthrow the democratically elected Republican government in 1936, Bethune felt compelled to assist. A socialist newspaper notice announcing the creation of a new committee to provide Spain with hospital supplies and medical staff caught his eye. Despite proving to be a mere concept at the time, the Canadian activist helped bring it into existence.

The result was the Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy, represented by Bethune himself when he travelled to Spain within a month. Arriving in Madrid on Nov. 3, 1936—on the eve of a nationalist offensive—the surgeon initially struggled to carve out his place, perhaps partly influenced by his controversial character.

Nevertheless, Bethune eventually succeeded by co-founding the Instituto Hispano-Canadiense de Transfusión de Sangre (the Spanish-Canadian Institute of Blood Transfusion), a mobile unit providing desperately needed blood to wounded soldiers and civilians. Though not alone in his endeavours, the realization that bringing the blood to the patients rather than the patients to the blood saved innumerable lives, not least within the fascist-besieged capital of Madrid.

Norman Bethune

(right) as part of the Canadian Blood Transfusion Unit which operated during the Spanish Civil War. [Wikimedia]

Bethune’s team witnessed the stream of humanity, saw the Italian and German aircraft strafing the crowds, and watched as enemy ships joined the slaughter.

For three days, the unit shuttled dozens of refugees, mostly families, to Almería in their ambulance, the members taking turns to sleep on the roadside. When the fascists later bombed Almería city square, Bethune counted at least 50 dead.

Thousands more were murdered during the tortuous journey, an atrocity, indeed a war crime, that the Canadian surgeon would describe as “a scar on my heart.”

But there were likewise problems within the unit itself. Fiercely independent and often argumentative, Bethune ran into conflict with his predominantly Spanish staff. Among the complaints was that he made no effort to learn the language.

With little tolerance for differing views, Bethune became increasingly reliant on alcohol. A love affair with a Swedish woman deemed suspicious further alienated him from team members. Worse, in March 1937, after the Spanish Republican authorities incorporated his unit into the military, Bethune railed against the bureaucracy that undermined his sense of self-determination in the field.

While still a respected figure, he was starting to wear out his welcome.

The precise circumstances surrounding his departure from Spain two months later remain uncertain. According to Bethune, he felt that the Instituto Hispano-Canadiense de Transfusión de Sangre was operating well enough without him. Another theory is that some of his colleagues conspired to remove him from the picture, albeit after recognizing his future value as a propagandist in Canada.

False accusations of being a spy did not help his case, nor did the fact that he made a propaganda film—Heart of Spain—without passing it through the censors.

And then there was his temperament. Brilliant yet arrogant with a contempt for authority, it seemed inevitable that Bethune’s personality, the same traits that had helped catapult him to Spain in the first place, would contribute to his downfall.

Of course, to those who benefited from his revolutionary service, such perceived character flaws meant little. In less than six months, Bethune had made an extraordinary impact in wartorn Spain. It was also destined to continue after he returned home where, embarking on a North American speaking tour, he inspired many, including medical experts, to directly and indirectly support the cause.

Bethune twice attempted to rejoin the cause himself. His first effort to kickstart a project for orphaned children stumbled when the Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy refused to fund the mission. He next tried to volunteer, by then aged 47, for service in the International Brigades, but he was again unsuccessful.

On Jan. 8, 1938, Bethune found a new outlet for his activism. Departing Canada for the last time, he and a Winnipeg nurse named Jean Ewen set out for China. There, the duo joined Mao Zedong’s communist Eighth Route Army, tasked with reorganizing its rudimentary medical practices amid the Sino-Japanese War.

Among Bethune’s achievements were performing surgeries, renovating medical facilities and training health-care practitioners known as Barefoot Doctors. He earned the admiration of the Chinese people by maintaining a rapport with the locals, respecting their traditions, and even donating his own blood when needed.

Blood had largely defined Bethune’s life, as it would his death.

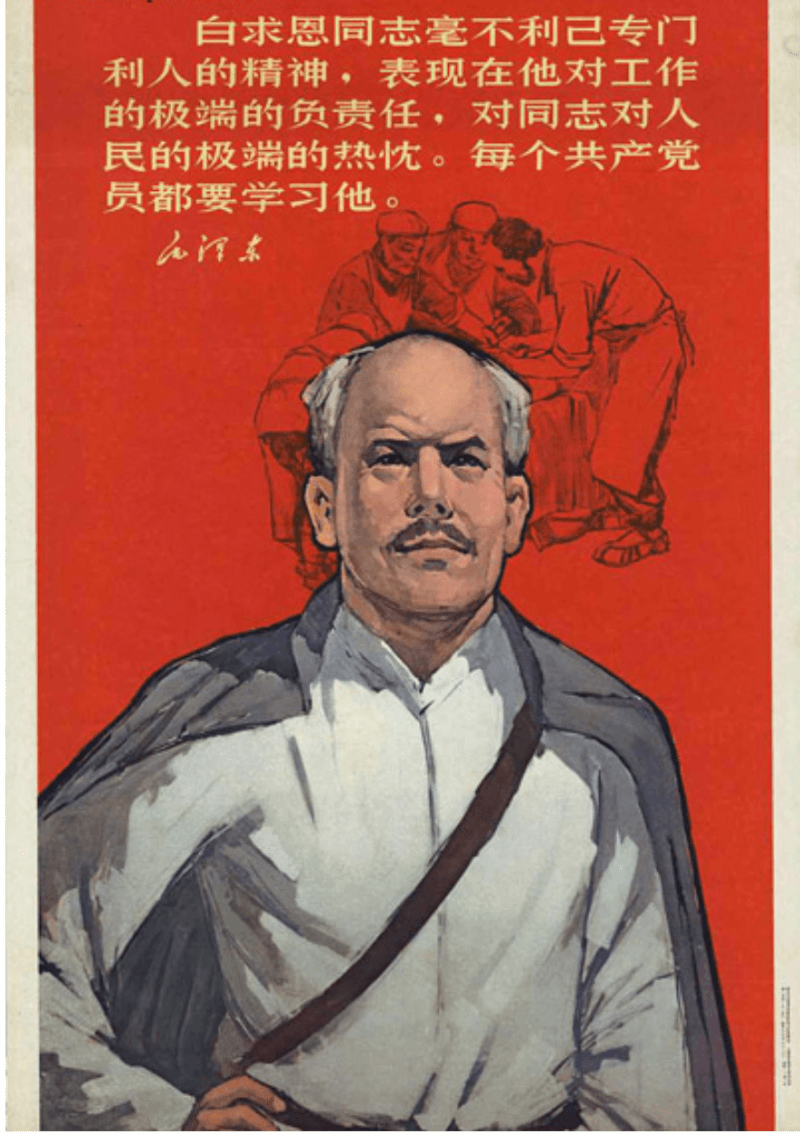

A 1968 propaganda poster depicting Bethune with a quotation from Mao’s eulogy for him. [Wikimedia]

He was right. The next day, Nov. 12, 1939, a combination of sepsis and gangrene—he refused to have his arm amputated—claimed him. He was just 49 years old.

Norman Bethune’s legacy, however, lives on through several acts of remembrance, especially in China where, even today, an essay written in memoriam by Mao Zedong remains mandatory reading. Ever the complicated figure, Canada’s gradual recognition of his accomplishments began in the 1970s and is arguably ongoing.

Advertisement