Winston Churchill, photographed on December 30, 1941, in the chamber of the Speaker of the House of Commons in Ottawa. [Yousuf Karsh]

Churchill served two stints as prime minister: 1940-1945 and 1951-1955. But it was during those first five years, as France fell to Nazi Germany and Britain faced a daunting onslaught, that he rose to power, prominence and ultimate victory—largely on the blustery winds of some of the greatest speeches ever written.

“All the great things are simple, and many can be expressed in a single word: freedom; justice; honour; duty; mercy; hope,” he said in summarizing what Adolf Hitler had set out to destroy.

But for decades, Churchill (born in 1874, a product of Victorian England and the imperialism and sense of superiority that went with it) preached the repressive tenets of social Darwinism. The theory applied the biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics. Thus, the wealth and power of the strong increase while those of the weak decrease.

Churchill’s racist history is not cut-and-dried.

Long after such ideas appeared to fall out of favour, Churchill embraced a hierarchical perspective of race that put whites at the top of the ladder and Blacks at the bottom. He advocated against Black or Indigenous self-rule in Africa, Australia, the Caribbean, the Americas and India, believing that British imperialism was for the good of the “primitive” and “subject races” of its colonies.

Churchill’s racist history is not cut-and-dried, however. It is, in fact, much more complicated than that—at times blatant, at other times confoundingly tolerant and seemingly progressive.

“Presenting an informed historical understanding of those opinions should not be misread as an attempt to justify them,” historian Richard Toye wrote for CNN in June 2020 after Black Lives Matter protesters defaced a Churchill statue in London.

“Nor should mentioning the other parts of Churchill’s record, notably his resistance to the Nazis and leadership during World War II, be seen as an attempt to argue that his racism pales into insignificance beside it.”

Churchill on horseback in Bangalore, India, in 1897. [Rare Historical Photos]

When concentration camps were built in South Africa for white Boers, he said they produced “the minimum of suffering,” although the death toll was almost 28,000.

When at least 115,000 Black Africans were swept into British camps, and 14,000 died, he wrote only of his “irritation that Kaffirs should be allowed to fire on white men.” Later, he boasted: “That was before war degenerated. It was great fun galloping about.”

In 1902, Churchill warned that the “great barbaric nations” would “menace civilised nations” and, advocating more conquest, declared that “the Aryan stock is bound to triumph.”

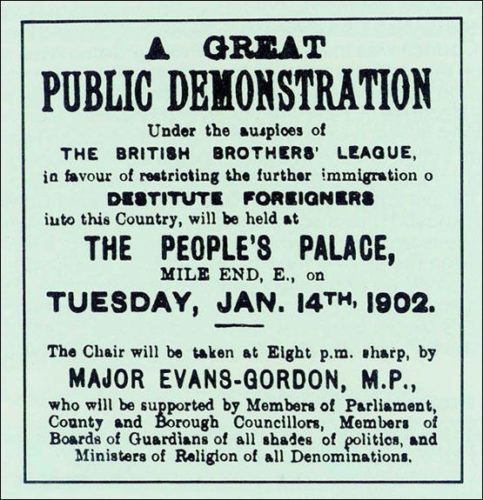

An anti-immigration poster from 1902, advertising a speech by William Evans-Gordon. [Wikimedia]

He declared himself a backer of “the old tolerant and generous practice of free entry and asylum to which this country has so long adhered and from which it has so greatly gained.” Then he crossed the floor to sit as a Liberal MP for two decades.

There, he pushed for the phasing out of indentured servitude by Chinese labour in South Africa and expressed concerns about relations between European settlers and the Black African populace. After the Zulu launched the Bambatha Rebellion in Natal, he complained about the “disgusting butchery of the natives” by Europeans.

In a 2010 review of Toye’s book, Churchill’s Empire, Johann Hari wrote in The Independent that there seems to have been an odd cognitive dissonance in Churchill’s view of the “natives.”

As a soldier, Churchill fought to suppress resistance to British rule in India.

“In some of his private correspondence, he appears to really believe they are helpless children who will ‘willingly, naturally, gratefully include themselves within the golden circle of an ancient crown,’” wrote Hari. “But when they defied this script, Churchill demanded they be crushed with extreme force.

“As Colonial Secretary in the 1920s, he unleashed the notorious Black and Tan thugs on Ireland’s Catholic civilians, and when the Kurds rebelled against British rule, he said: ‘I am strongly in favour of using poisoned gas against uncivilised tribes.… [It] would spread a lively terror.’”

Churchill raged that Mahatma Gandhi, the father of peaceful resistance, “ought to be lain bound hand and foot at the gates of Delhi, and then trampled on by an enormous elephant with the new Viceroy seated on its back.”

As the resistance swelled, he announced: “I hate Indians. They are a beastly people with a beastly religion.”

When imperialist British policies caused a 1943 famine in Bengal during which up to three million people starved to death, Churchill bluntly refused British officials’ pleas for food supplies to the region, blaming the Bengalis for “breeding like rabbits” and asserting that the disaster was “merrily” culling the population.

Lord Archibald Wavell, the penultimate viceroy of India, once said that Churchill “has still at heart his cavalry subaltern’s idea of India; just as his military tactics are inclined to date from the Boer War.”

After his presidency, George W. Bush (left) was inspired to paint, just as Winston Churchill (right) did in the later years of his life. [Smithsonian Museum; International Churchill Society]

In reply to the assertion that everybody thought like Churchill in those days, Toye asserts they did not. Even at the time, the pugnacious parliamentarian was seen as occupying the “most brutal and brutish end of the British imperialist spectrum.”

Which leads to the question: was Churchill’s moral opposition to Nazism a charade designed to cover up for the fact he was just defending the British Empire from a rival?

Toye says Churchill’s worldview was far from static and shifted as much for political expediency and image-crafting as for any genuine sense of enlightenment or otherwise.

He may have been a thug, but he knew a greater thug when he saw one.

Yet, he said, “portraying Churchill as the root of all wickedness, as some of the more extreme social media comments appear to do, is as problematic as viewing him as the single-handed savior of freedom and democracy.”

“By elevating him to a place of supreme importance—albeit by presenting him as uniquely wicked rather than splendidly virtuous—it reinforces Churchill’s own theory of history as driven by great white men. That is a vision from which, surely, we urgently need to break free.”

In his book, Toye quotes U.S. civil rights leader Richard B. Moore, who called it “a rare and fortunate coincidence” that at the moment that Churchill ascended to the prime minister’s office, “the vital interests of the British Empire [coincided] with those of the great overwhelming majority of mankind.”

Hari says that may be too soft in its praise.

“If Churchill had only been interested in saving the Empire, he could probably have cut a deal with Hitler,” he wrote. “No: he had a deeper repugnance for Nazism than that. He may have been a thug, but he knew a greater thug when he saw one—and we may owe our freedom today to this wrinkle in history.”

Churchill waves with a victory sign in London after he broadcast to the nation that the war with Germany had been won. [Major W.G. Horton/Wikimedia]

“In resisting the Nazis, he produced some of the richest prose-poetry in defence of freedom and democracy ever written,” said Hari. “It was a cheque he didn’t want Black or Asian people to cash—but they refused to accept that the Bank of Justice was empty.”

Ghanaian nationalist Kwame Nkrumah wrote that “all the fair, brave words spoken about freedom that had been broadcast to the four corners of the earth took seed and grew where they had not been intended.”

Churchill lived to see democrats across Britain’s dominions and colonies—from nationalist leader Aung San in Burma to Jawaharlal Nehru in India—use “his own intoxicating words” against him, Hari said in his 2010 essay.

“Ultimately, the words of the great and glorious Churchill who resisted dictatorship overwhelmed the works of the cruel and cramped Churchill who tried to impose it on the darker-skinned peoples of the world,” he wrote two years into Obama’s first term as president.

“The fact that we now live in a world where a free and independent India is a superpower eclipsing Britain, and a grandson of the ‘savages’ is the most powerful man in the world, is a repudiation of Churchill at his ugliest—and a sweet, ironic victory for Churchill at his best.”

Advertisement