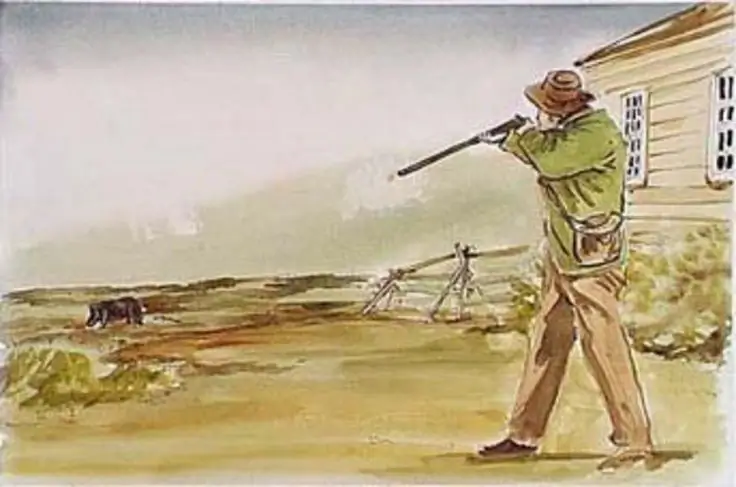

Lyman Cutlar shooting a wild hog. [Wikimedia]

In 1859, having settled on San Juan Island—land contested between the British Empire and the United States near Vancouver Island—he encountered swine eating his vegetables. These weren’t just any old hogs, however, but ones belonging to the ever-influential Hudson’s Bay Company, a British-founded institution that had long acted as the regional powerhouse.

Initially, Cutlar showed a degree of patience, merely chasing the livestock off his plot. But on June 15, having spotted a lone pig rooting through his garden once more, his patience ran out.

Cutlar grabbed his gun and, in a moment of rage, shot the creature. Unknown to him at the time, his actions would kickstart the so-called Pig War.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, since both the American Revolution and the War of 1812 were still within living memory, it didn’t take much to exacerbate tensions between the expansionist U.S. and the British Empire.

Though both competing powers had made previous border agreements, ambiguities remained—not least on and around San Juan Island.

It was under these circumstances that Cutlar, a former gold prospector who had first come to B.C. in the fervent hope of finding his fortune, instead found himself embroiled in a potentially catastrophic global confrontation.

The farmer regretted his decision the second he pulled the trigger.

Alas, it was too late; the pig was dead.

British officers outside their quarters on San Juan Island. [Archives Canada]

Tensions ratcheted up further with the arrival of British and American reinforcements.

Cutlar confessed to his momentary lapse of reason while speaking to the local HBC authority, Charles Griffin. He offered to pay damages for the misstep, but Griffin flew into a rage, threatening to evict him and all other Americans before demanding he pay $100 for a $10 pig. Incensed, Cutlar stormed out.

The confrontation escalated when U.S. Brigadier-General William S. Harney, a hot-headed anglophobe, intervened. The brash commander ordered a small detachment under Captain George Edward Pickett—the soon-to-be-famous Confederate general, but a then-largely-unknown officer—to San Juan in July 1859. In response, the Royal Navy dispatched ships to the area.

Many colonists, including local Governor James Douglas, demanded retribution as both sides began spoiling for a fight. Yet in the eyes of Rear Admiral Robert Baynes, the senior British naval officer who later presided over the affair, neither belligerent had any interest in “a war over a squabble about a pig.”

Tensions ratcheted up further with the arrival of British and American reinforcements, although cooler heads had, so far, prevailed. Meanwhile, the crisis rolled into the autumn due to slow-moving communiques between Washington and London. The situation remained a powder keg.

Nevertheless, hope came in the form of overall U.S. Army commander Wilfred Scott. A renowned hero of the 1846-48 American-Mexican War, the lieutenant-general used diplomacy to find a compromise, returning San Juan to its joint-occupied state with a promise for a permanent solution.

Together with British Rear Admiral Baynes, who flatly refused orders for even greater escalation amid the dispute, Scott helped prevent a farce of a conflict. It would also be a well-timed decision as, from April 1861, American interests turned soundly inward upon the outbreak of the U.S. Civil War.

But geopolitical headaches, as well as an eventual resurgence of tension—albeit to a much lesser degree—still awaited all parties concerned.

British camp on San Juan Island. [Archives Canada]

Ultimately, the emperor ruled in favour of the Americans’ preferred boundaries.

The 1871 Treaty of Washington settled many border issues between the United States and the newly created Dominion of Canada—the foreign affairs of which were still handled by Great Britain. When the revived matter of San Juan Island arose, however, German Kaiser Wilhelm I was assigned the role of arbitrator. Ultimately, the emperor ruled in favour of the Americans’ preferred boundaries. The island therefore fell under U.S. control in October 1872.

The Pig War—not to mention the poor slaughtered swine that started it—had been put to rest once and for all. Today, the stranger-than-fiction scene has been commemorated at the U.S. San Juan Island National Historical Park.

But beyond the ridiculousness of the affair is an unavoidable truth. In a battle of egos, military bluster and pettiness, the 1859 Pig War represents the fragility of peace, the potential cost of rash decisions and the virtues of dialogue.

Advertisement