Joseph Goebbels (left) and Adolf Hitler watch the Olympic Games in Berlin in August 1936. Hitler hoped the spectacle would showcase Germany’s “rebirth” and promote Nazi ideals of racial supremacy and antisemitism.

[Files]

Jesse Owens’ four gold medals “humiliated the master race” and “single-handedly crushed Hitler’s myth of Aryan supremacy,” wrote ESPN columnist Larry Schwartz.

Owens’ achievements at the Berlin Games would not change the course of history. They wouldn’t prevent a world war or the Holocaust. They wouldn’t even alleviate racism in his native United States.

“When I came back to my native country, after all the stories about Hitler, I couldn’t ride in the front of the bus,” said the sharecropper’s son from Oakville, Ala. “I had to go to the back door. I couldn’t live where I wanted.

“I wasn’t invited to shake hands with Hitler, but I wasn’t invited to the White House to shake hands with the President, either.”

Berlin’s selection as the Games’ host city took place in 1931, two years before Hitler was appointed chancellor. But the evil nature of his Nazi regime became evident immediately, and by 1935 German Jews had lost virtually all their rights.

Still, the Games went ahead despite protests—and some countries, including the U.S., actually removed Jews from their Olympic teams so as not to offend Germany’s Nazi regime.

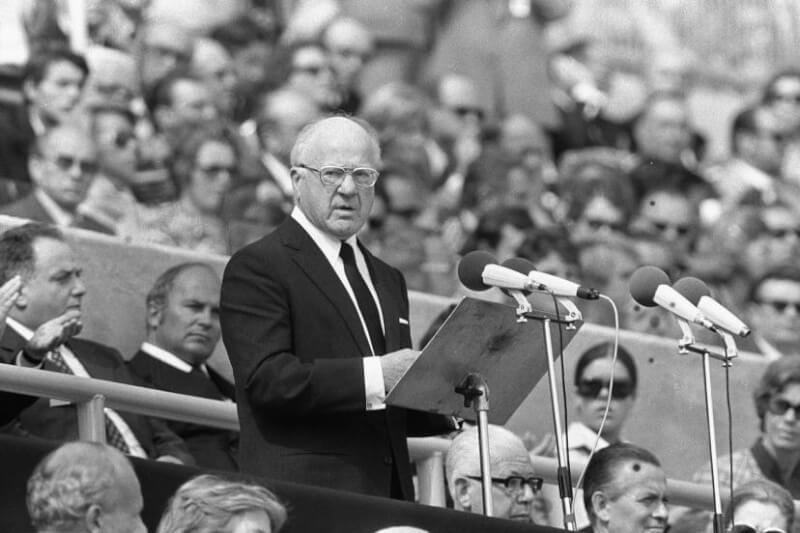

“Politics has no place in sport,” declared Avery Brundage, future IOC president and the head of the U.S. Olympic Committee at the time. Initially doubtful, Brundage became a Nazi apologist and one of the biggest backers of a Berlin Olympics.

He made a fact-finding trip to Germany in 1934 to determine whether German Jews were being treated fairly. He professed to find no discrimination when he interviewed Jews via Nazi translators—and commiserated with his hosts that the Chicago sports club he belonged to didn’t allow Jews either.

Jesse Owens salutes the American flag from the medal podium after receiving long jump gold at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

[Files]

In November 1935, the University of Manitoba hosted a debate on whether the country should attend the Berlin Olympics. Participants voted 90-20 for a boycott.

Participation proponents argued that a withdrawal would antagonize Germany and compound Nazi hostility toward Jews. They claimed that the Games were under the direction of the IOC, which prohibited racial and religious discrimination. Those opposing said competing would signal tacit support for Nazi racial policies.

In a Nov. 1, 1935, piece, Vancouver Sun sports columnist Hal Straight said the Berlin Games should be cancelled altogether.

“The Olympics do not belong to Hitler, nor Germany,” he wrote. “They belong to the world and are just being staged in Germany to that country’s request because it brings great beneficial returns. Hitler is being done a favor.

“I suggest all the flags be put together, made into a nice bright blanket and wrapped around Herr Hitler’s head, thus boycotting his athletic plans and waiting for the Olympic games until another year.”

To the shock of many, Canadian Olympic officials ignored the protests. The annual meeting of the Amateur Athletic Union of Canada, held behind closed doors in Halifax, did not air the issue. Its resolutions committee instead suggested following Britain’s lead and attending the Games.

According to the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, the resolution was approved without discussion. Canada would send 79 men and 18 women to Berlin. They earned a gold medal, three silver and a bronze.

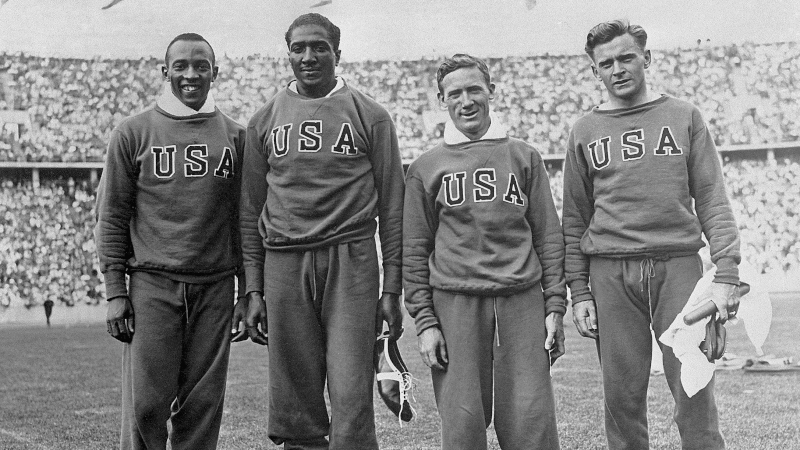

Fifty-one countries—14 more than participated at Los Angeles in 1932—gave Hitler what he wanted. The U.S. even switched out two Jewish relay runners, Sam Stoller and future New York broadcaster Marty Glickman, for Owens and Ralph Metcalfe.

Spain, on the other hand, boycotted Berlin and staged its own parallel “People’s Olympiad.” It was attended by some 6,000 athletes from 49 countries.

Owens (left) with U.S. 4x100m relay teammates Ralph Metcalfe, Foy Draper and Frank Wykoff.

[Files]

More significantly, the Games also provided the Nazi dictator with a stage on which he could promote his party’s ideals of racial supremacy and antisemitism.

German Jewish athletes were prevented from participating in the Games after the official Nazi Party paper, the Völkischer Beobachter, declared that Jews and Blacks should be barred.

The previous Games in Los Angeles, mounted amid the Great Depression, were said to have turned a US$1-million profit. Hitler was bound and determined to outdo the Americans.

He commissioned a new 100,000-seat track-and-field stadium along with six gymnasiums and other smaller arenas. The 131-hectare sports complex, located about eight kilometres west of Berlin, cost 42 million Reichsmarks (about US$375M today). They were the first Games to be televised and radio broadcasts reached 41 countries.

One of history’s most talented, innovative and controversial filmmakers, Leni Riefenstahl, was paid $7 million by the German Olympic Committee to film a pioneering four-hour documentary, Olympia, on the Games.

By the time the Games were held, German Jews had lost citizenship and were banned from universities and many fields of work, their businesses boycotted and vandalized. They were regularly harassed in the streets, and worse.

The persecution and violence would escalate until, finally, in 1941, the Nazis implemented the “Final Solution,” a euphemism for the systematic extermination of Europe’s Jewish population.

The president of Germany’s Olympic committee, Dr. Theodor Lewald, was dismissed after it was discovered his paternal grandmother was Jewish. He was replaced by Hans von Tschammer und Osten, a high-ranking member of the SA, or Sturmabteilung, the Nazi Party’s original paramilitary wing.

In one of his first acts as committee president, Osten declared the German Olympic team would be Aryans-only. Some of the banned athletes were world-class in their fields, including tennis star Daniel Prenn and boxer Erich Seelig.

Prenn, Seelig and other German athletes left the country to pursue their careers abroad. Prenn played tennis in England; Seelig moved to the U.S.

The Nazis also disqualified Romani people, including Germany’s middleweight boxing champion, Johann Trollmann.

U.S. Olympic Committee president Avery Brundage initially supported a boycott of the Berlin Games, then changed his mind after visiting Nazi Germany.

[Files]

The Amateur Athletic Union doubled down on its call for a boycott after Brundage announced on Sept. 26, 1934, that the U.S. Olympic Committee had officially accepted the invitation to participate in Berlin.

The union’s leader, Jeremiah Mahoney, said U.S. participation in the Games meant nothing less than “giving American moral and financial support to the Nazi regime, which is opposed to all that Americans hold dearest.”

American Jewish and Christian leaders, along with liberal politicians, 41 college presidents and dozens of trade union leaders demanded Olympic and economic boycotts of Nazi Germany.

But this was the same America that would host a Nazi rally in 1939, sold out to a crowd of 20,000 at Madison Square Garden in New York. Held two days before George Washington’s birthday, the rally stage featured a huge portrait of America’s Revolutionary War hero and first president flanked by swastikas.

Brundage pooh-poohed the critics, claiming the Olympics were meant for “athletes not politicians.” He swayed the perspective of numerous U.S. athletes and, when the Amateur Athletic Union took its final vote on Dec. 8, 1935, the proposal to boycott was defeated, barely.

The 1936 U.S. Olympic team was the largest fielded by the country at the time, with 312 athletes, including 19 African Americans and five Jews. Glickman and Stoller’s coach informed them at the last minute that they would be replaced. Glickman later speculated Brundage, to avoid upsetting Hitler, was behind the decision.

The international pressure had gained such momentum that the Nazis allowed a part-Jewish athlete, 1928 fencing gold medalist Helene Mayer, to return to the German Olympic team. She won silver in Berlin. Theodor Lewald, also of Jewish descent, was appointed an “adviser” to the Reich’s Olympic organizing committee.

The Nazis assured the IOC that Black athletes would be treated well in Germany, and reluctantly agreed to let foreign Jews participate. Numerous Jewish athletes from the U.S., Canada, Austria and France nevertheless withdrew in protest.

“To the surprise of his top aides Hitler became genuinely interested in the various sporting matches and took great delight in every German victory.”

German broadcasters and journalists referred to Owens as “the Negro Owens” and his 18 African American teammates as “America’s Black auxiliaries,” thereby implying they were not full-fledged team members.

Owens became an instant superstar in Berlin, in spite of it all. German fans chanted his name whenever he entered the Olympic stadium and mobbed him for autographs in the street.

Hitler, however, never met him. On the first day of the track-and-field competition, the Nazi leader left the rain-threatened competition and missed greeting the three American medal winners in the high jump, two of whom were Black.

Upset Olympic officials advised Hitler that either he should receive all the medal winners or none of them. Hitler opted to receive none. African American athletes would go on to win 14 track-and-field medals.

Owens took gold in the 100 metres, long jump, 200 metres and 4×100-metre relay. He was the Games’ most successful athlete, and his feats were touted in the world press as proof that the Nazi “master race” was a myth.

Hitler’s minister of armaments and war production, Albert Speer, wrote that the Nazi leader “was highly annoyed by the series of triumphs by the marvelous colored American runner, Jesse Owens. People whose antecedents came from the jungle were primitive, Hitler said with a shrug; their physiques were stronger than those of civilized whites and hence should be excluded from future Games.”

Owens later said he didn’t feel snubbed by his Nazi host. At one point during the track-and-field competition, he said, he glanced up at Hitler in his box seat and der Führer stood and waved to him. Owens waved back.

Hitler acquiesced to the wishes of IOC officials and maintained a deliberately low-key presence throughout the 14-day spectacle.

It proved “a good opportunity for the Führer to appear calm and dignified among the thousands of international observers who were watching his every move,” said The History Place, an online journal, in a 2001 article.

“To the surprise of his top aides Hitler became genuinely interested in the various sporting matches and took great delight in every German victory.”

The 52-hectare Olympic Village was a unanimous hit, considered the best ever. It had been constructed by the Wehrmacht under the direction of its designer, Captain Wolfgang Fuerstner. Fuerstner, however, was demoted shortly before the Games because of his Jewish ancestry. He was relegated to a subordinate position under his non-Jewish replacement, Lieutenant-Colonel Werner Gilsa, who received all the credit and accolades that Fuerstner had earned.

Fuerstner was forced to attend a lavish banquet honouring Gilsa two days after the Games ended. After it was over, he went back to his barracks and shot himself. The Nazis claimed he had died in a car accident and gave him a full military burial.

“The only time the black fist has significance is when there’s money inside.”

Owens would be given a ticker-tape parade along Manhattan’s Canyon of Heroes. Afterward, he wasn’t allowed to pass through the main doors of the Waldorf Astoria New York. They made him go to the reception honouring him in a freight elevator.

He struggled to find work and took on menial jobs as a gas station attendant, playground janitor and manager of a dry-cleaning firm. He sometimes raced against motorcycles, cars, trucks and horses for cash prizes.

“People say it was degrading for an Olympic champion to run against a horse, but what was I supposed to do?” he once said. “I had four gold medals, but you can’t eat four gold medals.”

He eventually filed for bankruptcy and was convicted of tax evasion. A lifelong Republican, his fortunes turned at the hand of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who made Owens a goodwill ambassador in 1955 and sent him to India, the Philippines and Malaya to promote physical exercise and American culture.

When African-American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos famously raised their fists on the medal podium at the 1968 Summer Games in Mexico City, Owens told them: “The black fist is a meaningless symbol. When you open it, you have nothing but fingers—weak, empty fingers. The only time the black fist has significance is when there’s money inside. There’s where the power lies.”

Four years later, he published the book I Have Changed.

“I realized now that militancy in the best sense of the word was the only answer where the black man was concerned, that any black man who wasn’t a militant in 1970 was either blind or a coward,” he wrote.

In 1972, Owens traveled to Munich for the Summer Olympics as a special guest of the West German government. He was greeted by West German Chancellor Willy Brandt and boxing legend Max Schmeling.

The Berlin Olympics would be the last Games for 14 years. On Sept. 1, 1939, the forces of Nazi Germany invaded Poland, sparking a world war that would become the deadliest and most destructive conflict in history.

Advertisement