“This is the most intriguing story I’ve ever come across,” remarked historian David O’Keefe about the loss of Lancaster bomber LL862 in July 1944. Coming from the best-selling author of revelatory read One Day in August: The Untold Story Behind Canada’s Tragedy at Dieppe, it could be argued that that’s really saying something.

Rather than one day, however, this latest mystery is shrouded in a single night.

The mostly Canadian eight-man crew of 101 Squadron—a formation specializing in state-of-the-art electronic warfare—had embarked on a bombing mission over Homberg, Germany. That they hadn’t returned wasn’t suspicious in itself. On the contrary, Royal Air Force Bomber Command had long endured appalling losses, both of men and machinery, in its raids over the Reich. What didn’t add up, however, were the precise circumstances in which two flyers survived while others had perished.

One, Bomb Aimer Lowell Kennedy Gwilliam of B.C., evaded capture as well as any in-depth explanation of what happened—or at least was unable to offer any comprehensive account. The other, Pilot Daniel Meier, spent the remainder of the war in German custody before disappearing at the conflict’s conclusion. No word came from the elusive Canadian until he resurfaced in East Berlin in 1952. His subsequent testimony, followed by an apparent government cover-up, suggested something strange, maybe even malicious, had been afoot.

Was Meier a deserter or perhaps worse, a defector? Moreover, to what extent had he been complicit in the deaths of six men? O’Keefe concedes that there are more questions than answers, even now, but he is in the process of uncovering the truth with the intention of publishing a book at some point next year. Legion Magazine spoke to O’Keefe, who presented a tantalizing teaser to the tale.

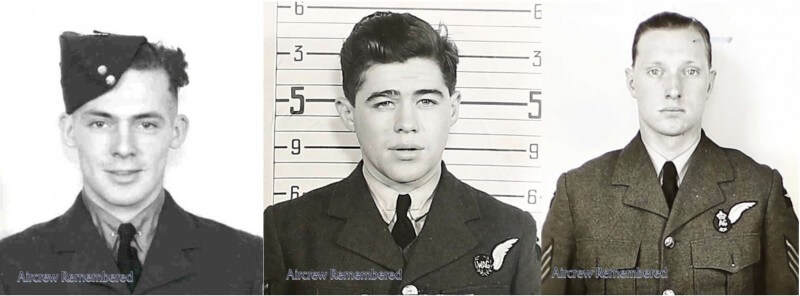

Pilot Daniel Meier (left) and crewman Sergeant Dominic Ianuziello, who died in the crash of Lancaster LL862. [aircrewremembered.com]

About discovering the tale of LL862

Like a lot of these things, you stumble upon such stories in the archives. You have no clue what you’re going to find until you open that file or turn that page. That’s certainly the case here, having happened upon it in 2006 while working on Dieppe.

I was looking into electronic warfare stuff at the time, and I basically came across the story of a Canadian pilot of the RAF’s 101 Squadron who had ended up being listed as missing, presumed dead, at the end of the war only to turn up very much alive many years later. For me, it’s been a 20-year process of unearthing the truth.

About what supposedly happened

Meier was born in Winnipeg to a large German and Russian immigrant family in a very impoverished situation. They got hammered really bad in the Depression and actually lost their farm. His father was an older man while his mother had been in and out of what they would’ve termed as mental institutions. One of his brothers had committed suicide, and another died swimming—potentially by suicide, too. This is to say there’s a history of familial poverty and mental illness.

Meier, who was quite aware of his German heritage, having spoken German as his first language, joined the air force in 1942. He had wanted to be a fighter pilot, but it wasn’t to be, so, he instead spent two years training as a bomber pilot. He’d gone to England, met his wife, and that’s how he ended up piloting LL862.

The aircrew, who are pretty tight by that stage, embark on their first operation over Homberg. The story is that after they reach the city, they drop their bombs and are on their way back when something happens, and the aircraft ends up going off the normal egress route, now headed southwest into France. It’s shortly after that that the plane and six of its crew members go down near a German Luftwaffe airfield.

One survived other than Meier, who came back to Canada and basically didn’t—or couldn’t—say anything. [Lowell Kennedy Gwilliam] had apparently bailed out earlier than Meier, where he then fell into the hands of the Belgian Resistance. He stayed in hiding for six-and-a-half weeks until the American army arrived and liberated the area. He later gave a testimony that was very simple and at times contradictory in the two versions he presented. Either way, with his post-traumatic stress disorder, the answers wouldn’t be coming from him.

Bomb Aimer Lowell Kennedy Gwilliam (left) was the only other survivor of the crash. Gunners Jack Nixon (centre) and Glenn Douglas died. [aircrewremembered.com]

Meier himself ended up in Stalag Luft III, best known for the Great Escape, where he stayed until December 1944, and in January 1945, he was forcibly marched out of Poland before appearing to fall into the hands of the Soviets. The war ends, and Meier’s wife, whom he’d married mere months before July 1944, expects him to walk through the door at any moment. Nothing. Not a thing. Not even a telegram.

The summer of ’45 turns into the summer of ’46, and his British wife is petitioning for more information. Of course, the [Canadian] government is reaching out to the Soviets to determine his whereabouts, but the Russians offer minimal cooperation.

Two years later, Meier is declared missing, presumed dead.

The wife gets on with her life, meets another man and falls in love. She is about to get married in 1952 when suddenly, a letter arrives from East Germany, addressed to her, and seemingly signed by her old husband. Bear in mind that she’s getting a widow’s pension at that time, so she heads into her local pension office, and their jaws, I imagine, just dropped. Anyway, she then makes arrangements to travel to Berlin.

She is joined [on the trip] by two pension clerks to find out what the hell is going on. The wife finally comes face to face with her husband—six-foot-one, blonde hair, blue eyes, very much like she remembered him apart from looking a bit haggard. Obviously, she asks, “where the hell have you been?” And he replies, “Okay, the reason I’ve reached out is because I’m so tired of living here in the East Bloc. I want to come home to Canada.” Ivy and the pension clerks finally ask why that would be an issue. His response: “Something happened on the plane that night.” Basically, he wants to know where he stands in the law in Canada.

Meier at long last provides some sort of explanation. Apparently, he says, he had spoken with his [German] father before leaving for the war, and he promised him that he would never drop bombs, “on people of the German race.”

Now, that had obviously happened over Homberg. But afterward, Meier said he’d never go through with it again. Thus, he says, “I made the decision that I was going to talk my crew into flying to Switzerland and us all giving ourselves up, where we would sit out the rest of the war. They weren’t having any of it. So, I decided that I would hand over the aircraft controls to the flight engineer and bail out alone over enemy territory, where I’d surrender. That’s when a fight broke out on the aircraft.”

Meier must have known that the flight engineer, who had minimal training at the controls, couldn’t possibly land the bomber back in England. But he still jumped.

By the time he hit the ground, he says, the aircraft had crashed in a ball of flames.

Meier’s wife, Ivy, is hearing all of this, and it’s around that particular point that the two seem to rekindle their relationship, taking off together back to his apartment in East Berlin—or at least that’s what we’re led to believe. She eventually decides to return and announces her intent to divorce her husband. That’s when it gets weird.

Now, of course, in sleepy Nottinghamshire back in those days, any kind of divorce, particularly from a man who has come back from the dead, is surely going to make front page news. The Canadian government pulls out all the stops, contacts British authorities, and cover up the divorce in the papers. But why, exactly, do they do it?

The Canadian and British governments had basically gotten fed up with going after deserters from the Second World War a few years earlier. They hadn’t granted them amnesty, but instead declared that they had never served in the first place. Now, the flipside to that is that it prevents anybody deemed never to have served from being tried in a military court. Civilian courts, meanwhile, have a different threshold for finding somebody guilty, meaning that Meier, in theory, could walk out scot-free.

What happened next? Was Meier’s version of events really the truth? You’ll just have to read the book in summer or fall of 2026 and draw your own conclusions.

This abridged interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Advertisement