An exhausted and oil-soaked Ken Rose, a Canadian engineer with Calgary-based Safety Boss, takes a break after a tough session at a wellhead in the Kuwaiti desert. [Sebastião Salgado]

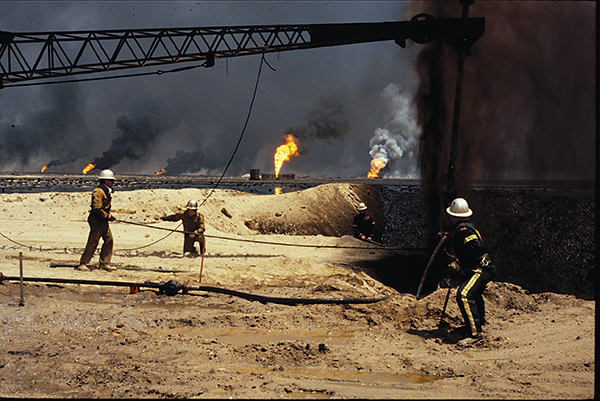

As soon as the bloodbath in the Kuwaiti desert ended, Canadian oil-well firefighters and BOMB disposal experts stepped up

Mike Miller figures there are three main reasons why his Calgary-based company, Safety Boss, put out more oil well fires than any other crew working in postwar Kuwait in 1991: the Canadians were mobile; they used chemicals instead of explosives to quell the fires; and they were colour-blind.

Safety Boss put out 180 of somewhere between 605 and 732 oil-well fires lit by Saddam Hussein’s troops as they evacuated occupied Kuwait and ran from coalition forces during the 43-day war to liberate the petroleum-rich country.

When the fighting was over, the firefighting began. Safety Boss was one of the original four firms dispatched to battle one of the century’s worst environmental disasters. The rest were all Texans—Boots & Coots, Wild Well Control and the legendary Red Adair. The project manager was Texan, too.

Safety Boss’s own impressive qualifications notwithstanding, the Americans had reputations backed by years of experience and well-crafted PR. They had egos the size of their great state, their own way of working, and no intention of changing it.

So when the Canadians arrived with shining red fire trucks and a planeload of other equipment, the Americans just rolled their eyes. Miller—whose father K.J. (Smokey) founded Safety Boss in 1956—was unfazed.

“We were kind of unwelcome guests,” he said in an interview with Legion Magazine. “The ‘young upstarts.’ The Texans just didn’t think we were qualified. We had different equipment than they did and they made fun of it.”

The Americans had first dibs on new equipment, and little inclination to share it or their evolving expertise in the unprecedented challenges they all faced.

“It really motivated our people, to be treated so poorly, and it was really the Canadian work ethic that made a huge difference,” said the CEO, who took over the firm from Smokey in 1979. “Everybody just went the extra mile every day.

“When we hired people we said, ‘Look, this is like the Stanley Cup and when we put you on the ice, if you don’t contribute, you’ll go home.’ And we stuck by that.”

With one more fire extinguished, a Safety Boss crew caps a wellhead. More fires await. [Safety Boss]

A well in the Burgan field can produce about 50,000 barrels a day, compared to a typical Canadian well at about 1,000. The fires burned about 10 million barrels each day. Huge lakes of oil—some several square kilometres in dimension, some burning—dotted the landscape.

Experts warned it could take five years to put the fires out. The job took 200 days.

Well firefighting was one of the most important and undoubtedly most successful elements of the extensive efforts to return the region to some degree of normalcy after Iraq’s president failed in hisw bid to make Kuwait his 19th province.

While army combat engineers cleared hundreds of square kilometres of mines and unexploded ordnance (UXO), and navy sailors boarded blockade-runners at sea, the Safety Boss crew was in the maelstrom of roiling fire and smoke that robbed lungs of oxygen and cast an otherworldly red-brown light over the entire region.

Canadian soldiers build accommodations for UN staff at a hospital in the demilitarized zone of southern Iraq. [John Isaac/UN]

Besides the fires, the oil-soaked Canadians and their skeptical associates endured extreme desert heat that often exceeded 50°C, negotiated scattered landmines and unexploded bombs, dodged poisonous snakes, and recoiled at repeated encounters with dead camels and the rotting bodies of Saddam’s hapless soldiers.

Miller, who comes from a diverse heritage, was prepared to take on qualified help from wherever he could get it, and he did. The Texans, not so much. They were “very racist,” he said. “I just had no time at all for racism of any type,” said Miller. “And that paid off for us because all the [third country nationals] wanted to work for us.”

The TCNs, as they were called, came from places such as Pakistan, Afghanistan, Egypt and the Philippines. They played a full part in the crew’s Thursday-night meetings on how to improve operations, and contributed significantly.

An Afghan backhoe operator working for the Canadians had been a doctor in his homeland. He came up with innovations that turned a six-hour job into a 30-second job. A trained mortician came in handy when calls to coalition forces and the Red Cross to collect the blackened corpses of Iraqi soldiers went unanswered. They buried more than 50. Another foreign national came up with ways to cut the crew’s set-up process on new wells from six hours to 30 minutes.

The retreating Iraqis had set explosives on either side of the wellheads, blowing up to a dozen wells at a time. Had they set the explosives farther down the wells, said Miller, they would have done a lot more damage.

As it stood, not a single well was lost, although the fires cost the Kuwaitis about a billion barrels of oil. The United Nations Compensation Commission granted Kuwait nearly $52.4 billion in war reparations from Iraq.

The Canadians’ use of fire-suppressant chemicals simplified and streamlined the process considerably. While the Texans had a complicated set-up that could take a week and had to evacuate the area before they blew a well, the Canadians would have some fires out in an hour. Still, the other crews adopted none of the Canadian methods.

“They would work right beside us, see what we were doing, but they’d never change. I just found that phenomenal, to tell you the truth.”

Counterintuitively, the most dangerous time was after the fires were out. In almost 30 cases, glowing charcoal reignited wells.

The crews called them “relights,” and they were the bane of their existence—especially dangerous because ongoing pressure from below would cause a fuel buildup before they erupted. The subsequent infernos would be much larger and more intense than the original ones. Good equipment and preventative relights to burn off the buildups saved lives.

Once the fires were out, the crews would then pump mud down the holes to kill the flow of oil and gas, remove the damaged equipment and replace the valves.

Despite several setbacks, “there were times where we literally did every well around the Texan crews and then moved on to another one while they were still setting up their fixed systems.”

Eventually, firefighting contracts were awarded to crews from 27 countries, but it was the original four who did the bulk of the work—90 per cent, by Miller’s estimate.

“It was an intense time,” said Miller. “I can’t say enough about the work ethic of Canadians in doing that impossible task. We were continually developing new processes. It made a big difference.”

The Kuwaiti desert was strewn with discarded and burned out equipment, cadavers, landmines and UXOs. Cleaning up the latter was the job of combat engineers and disposal teams.

As a Canadian army captain, Fred Kaustinen was appointed deputy commanding officer just as 300 members of 1 Combat Engineer Regiment (1 CER) took up residence north of Kuwait City in April 1991, about six weeks after the fighting ended.

Ahead of them lay a demilitarized zone (DMZ) along the Kuwait-Iraq border, 200 kilo-metres long by 13 kilometres across. It was the Canadians’ job to clear routes into the area, clear the DMZ itself, and build base camps for UN observation posts along the border using trailers from Alberta Trailer Corp. (ATCO).

A live Russian RGD-5 fragmentation grenade lies in the desert of Kuwait. [Tom Oates/Wikimedia]

Canadian engineers cleared more than 1,000 kilometres of new track. But the job of keeping 2,000 kilometres of existing roads and track passable and safe was among the biggest challenges they faced. Sand could drift to depths of 1.5 metres over the course of a day. Winds blew UXOs onto the tracks constantly, requiring daily inspections.

There were hundreds of thousands of mines, but the UXOs posed the greater threat. The desert was littered with live bomblets and cluster munitions, many with small parachutes attached. Undetonated after hitting the desert sand, they moved constantly. The encroaching heat of summer would even cause some to explode.

“They were first-generation smart cluster bombs and area bomblets,” said Kaustinen. “I think partly because they were first-generation, they had a high dud rate.

“We didn’t even know of these munitions beforehand, nor did we have the schematics. Our specialists with additional explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) training, they figured out what was magnetic fusing, what was whatever—because you don’t want to use a mine detector around magnetic fusing, for instance.”

They scavenged abandoned equipment and improvised as they went. Mechanics had to learn their way around eastern European equipment, cannibalizing three Czech bulldozers to keep one running. Even their desert fatigues were British and boots were Saudi—much cooler than the woven nylon and black leather in which they were deployed into the 55°C heat of the Kuwaiti desert. They eventually switched from their issue wool socks to desert cotton.

The Canadians made it through the tour casualty-free, but not so some of the other units who had been assigned sectors in Kuwait. Some suffered more casualties than they did did in the actual fighting.

On July 12, 1991, an American brigade-sized unit and 250 British troops stationed next door to the Canadians were hit by a series of massive explosions after a squadron-load of munitions parked in a camp compound was detonated when an ammunition carrier loaded with 155-millimetre artillery shells overheated and caught fire.

An evacuation was still underway when the ammunition carrier exploded at 11 a.m. Artillery bomblets were thrown over nearby combat-loaded vehicles and ammunition stocks, setting off a series of blasts over several hours.

The UN Iraq-Kuwait Observation Mission headquarters located in the middle of the demilitarized zone where 1 Combat Engineer Regiment worked to clear mines and unexploded ordnance along sand-swept desert tracks. [John Isaac/UN]

“We ended up rescuing a bunch of Americans from that one,” said Kaustinen, who joined the military in 1979, attended Royal Military College, and retired a major in 1999. “The whole unit was lost, basically. There was way more battle equipment lost in that one fire than during the combat op.”

Indeed, the destruction was overwhelming: 102 vehicles damaged or destroyed, including four M1A1 Abrams tanks. More than two dozen buildings were damaged along with almost US$15 million in ammunition destroyed.

Some problems followed 1 Combat Engineer Regiment home. In the months and years after his unit returned, Kaustinen took up the cause of his soldiers, 62 of whom were complaining of health issues ranging from aches and respiratory problems to kidney and liver disease. One died of a brain tumour; another from Hodgkin lymphoma.

Other coalition governments came to formally recognize the variety of complaints as Gulf War illness. But Kaustinen’s repeated appeals have never received official acknowledgement from Ottawa. In 2006, military ombudsman Yves Côté concluded that the engineers weren’t suffering a greater rate of illnesses than other veterans. The result was that many were released with limited care and compensation.

“The Canadian military is built on trusts,” said Kaustinen. “One of the most sacred trusts is that if a soldier is injured, he/she and family will be taken care of. This was not the case with many of the soldiers of 1 CER (Kuwait).”

Richard Delve, a cook with the Canadian Support Unit, developed ulcers and Crohn’s disease; he had a liver transplant in 2011 and lost his colon and large intestine in 2014, shedding 30 kilograms in the process.

Delve was medically released in July 2005, six months shy of his 20th enlistment anniversary. The six months limited his pension to 38 per cent of his service salary instead of 40.

He suspects the barrage of inoculations they received prior to deploying may have contributed to his health issues, although others have pointed to a variety of concerns, from depleted uranium in munitions to smoke from the well fires. Miller says he has not heard of any related illnesses among his firefighters.

Despite all he has suffered, Delve says he would do it all again “in a heartbeat.”

“Even knowing what I know now,” said the veteran of three overseas tours. “The experiences I’ve had; the friends that I’ve made; the buddies that I’ve served with. The people are second to none. I’d do it all again, no problem.”

“They were good guys,” said Kaustinen. “They were just ordinary people called to do some rather unnatural work in extraordinary circumstances.”

Advertisement