A statue of Gudrid the Far-Travelled stands in her former home at Glaumbær, Iceland.[Wikipedia]

Born in 10th century Iceland, Gudrid sailed into the unknown aboard rudimentary longships, crossing the North Atlantic eight times, then trekking across the European continent and back again.

She journeyed to Greenland, Scandinavia and North America, where she gave birth to the first European born in the New World, Snorri Thorfinnsson, nearly 500 years before Christopher Columbus was credited with discovering the Americas.

An early convert from the pagan Norse religion to Christianity, she later went on a pilgrimage to Rome, where some believe she met the pope.

Her exploits are recorded in two Viking accounts, The Saga of Eirik the Red and The Saga of the Greenlanders, much of them confirmed by archeological evidence, notably at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland where she lived for three years.

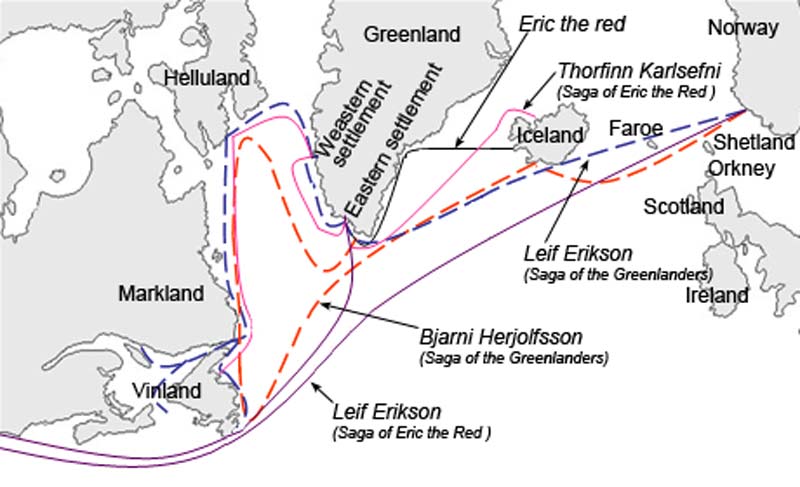

Viking settlements were scattered all over Scandinavia and by the 10th century had reached North America. [Wikipedia]

The discovery “lays down a marker for European cognizance of the Americas, and represents the first known point at which humans encircled the globe.”

Using radiocarbon dating on wood the explorers harvested on the island’s Great Northern Peninsula, scientists pinpointed the felling of trees at the site to precisely 1021 AD, long before Columbus dropped anchor off the Bahamas in October 1492.

“The Vikings (or Norse) were the first Europeans to cross the Atlantic,” declared a peer-reviewed article in the scientific journal Nature.

The discovery “lays down a marker for European cognizance of the Americas, and represents the first known point at which humans encircled the globe,” it said. “It also provides a definitive tie point for future research into the initial consequences of transatlantic activity, such as the transference of knowledge, and the potential exchange of genetic information, biota and pathologies.”

“Viking women were as courageous and as adventurous as Viking men and there were far fewer limitations on the life of a woman in those times.”

Long-time Parks Canada archeologist Birgitta Wallace, a co-author of the study featured in Nature and one of the world’s foremost experts on Vikings in North America, told Legion Magazine at the time that the Norse explorers likely arrived in Newfoundland years before they cut the wood on which the finding was based.

Much of Gudrid’s story will never be confirmed, but what is known reaffirms the belief that “Viking women were as courageous and as adventurous as Viking men and that there were far fewer limitations on the life of a woman in those times than we may think,” a Gudrid biographer, Nancy Brown, told Smithsonian Magazine in 2021.

The accounts of Gudrid in The Saga of Eirik the Red and The Saga of the Greenlanders, known collectively as The Vinland Sagas, differ slightly. In the former, she is poor and ends up shipwrecked en route to Greenland. In the latter, she’s wealthy and survives a harsh Greenland winter before travelling to North America, or Vinland, as the Norse called it.

Norse explorers took multiple sailing routes to Greenland, Vinland (Newfoundland), Helluland (Baffin Island) and Markland (Labrador). They were documented in the sagas of Eirik the Red and the Greenlanders. [Wikipedia]

Both trace her birth to Iceland in the late 10th century. At about 15, she travels with her father, Thorbjorn of Laugarbrekka, to Greenland, where Thorbjorn’s friend Eirik the Red is establishing a new Viking settlement.

Gudrid marries Eirik’s younger son, Thorstein, brother of the first European known to have set foot in North America, Leif Erikson. Thorstein sets sail for Vinland. The Greenlanders saga says Gudrid accompanies him. But they are forced to turn back, and make Greenland just before a harsh winter sets in.

Thorstein and many more die. His teenaged widow survives and returns to the main Greenland settlement. Both sagas report that she marries the Icelandic merchant Thorfinn Karlsefni, whose nickname means “the makings of a man.”

The couple sail to the New World, where Snorri is born, and three years later they return home. One of the sagas reports that the family visits Norway. The Saga of the Greenlanders notes that Thorfinn dies. Both accounts say Gudrid settles in Iceland at a farm called Glaumbær.

The Greenlanders saga says in her 40s or 50s, Gudrid embarks on a pilgrimage to Rome, making the journey almost entirely on foot before returning to her farm to live out her days as a “nun and recluse.”

“The Gudrid presented in both sagas is dignified and sensible,” wrote Sarah Dunn for Smithsonian. “In Eirik, she’s the ‘fairest of women’ and has a lovely singing voice.

“In Greenlanders, she’s described as knowing ‘well how to carry herself among strangers’—a reference to a later scene in which she speaks to an Indigenous North American woman.”

Archeologists uncovered three turf dwellings, a forge and four workshops at L’Anse aux Meadows some 60 years ago. Nails and wood shavings found scattered on the workshop floors suggest Viking settlers repaired boats there.

While surveying the site in 1975, Wallace’s team found proof that at least one Viking woman lived in Newfoundland nearly 1,000 years ago.

“I have no problem with Gudrid being here. She was!”

To the untrained eye, the object might have looked like an oddly shaped rock with a hole in it. But Wallace recognized the stone as an authentic Viking-era spindle whorl. It would have been fixed to the end of a rod used to spin thread.

The remnants of the Viking settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows were uncovered more than half a century ago on Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula. [Wikipedia]

Common sense—and more recent scientific evidence—would suggest it’s unlikely she was the only woman at L’Anse aux Meadows.

A 2014 study used mitochondrial DNA evidence to show that Norse women joined their men for Viking-Age migrations to England, the Shetland and Orkney islands and Iceland, and were “important agents in the processes of migration and assimilation.”

Just five known manuscripts of The Saga of Eirik the Red and one manuscript of The Saga of the Greenlanders are known to survive. The earliest known version of Eirik the Red was penned at an Icelandic monastery between 1306 and 1308 by Hauk Erlendsson, an adviser to the Norwegian king.

Hauk copied Eirik’s saga from his grandfather’s version of the story and added in a family tree, tracing his own ancestry back to Gudrid and her son Snorri. Scholars believe the lineage is accurate.

Explains Brown: “Icelanders were very interested in genealogy.… You knew who you were related to and you kept track of your genealogy very carefully. And the fact that Hauk traced his own genealogy back to Snorri proves that these really were real people.”

Advertisement