It mattered not that the May 7, 1945, announcement had been leaked earlier than authorities had intended. Cheers soon rang out across the city of Halifax and neighbouring Dartmouth as spontaneous celebrations erupted in the streets.

The 19-year-old from Belleville, Ont., who was serving in the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve thought little of his duties aboard HMCS Cobalt. Who, anyway, would need a sick berth attendant when the greatest issue, both over the coming hours and on VE-Day, was ensuring that service personnel and civilians alike savoured the moment?

Douglas reflected on his parents and how they would mark the historic occasion back home. He wondered, too, what he would write of his own experiences.

His medical skills, it would transpire, were destined to be critical. The young corvette crewman’s next letter to family, meanwhile, would be laced less with exuberance and gratefulness and more with horror, angst and sheer disgust.

“If we live to be 100,” he penned in the immediate aftermath of what was to become the Halifax VE-Day riots, “…we’ll shudder at the thought of it.”

The Maritime port had long been a powder keg.

Effectively on the front lines throughout the Battle of the Atlantic, Halifax was a hub of wartime activity from the conflict’s onset. Allied convoys transporting munitions, supplies and troops assembled and departed from its harbour; local industry was booming; and civilians grew

accustomed to the sea of uniforms.

As soldiers, sailors and airmen flooded into the city, the overall population swelled by an estimated 60 per cent between 1939 and 1944. Initially, these military men and women received a warm Nova Scotian welcome, but such hospitality was eventually replaced by ambivalence.

One of the primary causes was a fundamental lack of accommodation. Halifax’s infrastructure couldn’t keep pace with the rapid growth of Canada’s forces and, thus, had maintained its prewar, small-town semblance. Service personnel sought billets within the city, competing with civilians in a bidding war that bred contempt. Most landlords were fair in rent prices, although the more devious inflated rates for uniformed newcomers, who often found themselves sardined into small apartments under spartan living conditions.

The situation became so dire that plans were hatched to place posters at Canadian railway stations urging visitors to avoid Halifax unless on official business. It was, according to one naval officer, an “overcrowded hellhole.”

Another issue was an increase in rationing. Partly due to the city’s enormous military presence—some 13,000-18,000 naval personnel alone resided there by May 1945—Haligonians felt these shortages more acutely than most.

Then there was alcohol. Antiquated liquor laws meant that personnel had startingly few opportunities to enjoy a drink. Wet canteens on base and government stores in Halifax were perhaps the best options, but even those came with certain limitations, not least the ban on liquor possession and consumption in barracks.

Those less fazed by legality could instead visit bootleggers and speakeasies.

Once, the privately-owned Ajax Club had quenched the thirst of innumerable sailors, only for Halifax’s temperance lobbyists to force its closure in early 1942. That perceived slight against naval ratings was neither forgiven nor forgotten.

Resentment between residents, who became jaded by the strain on local facilities, and military members, who felt gouged by landlords and stifled by archaic rules, continued to fester, occasionally exhibited in alcohol-fuelled offences ranging from vandalism to property destruction to theft and assault.

On Dec. 2, 1944, a tram became the target of naval ire, having come to epitomize all that was considered wrong with Halifax. The streetcars were old, congested and uncomfortable, not to mention scarce. Inebriated sailors smashed windows and damaged the vehicle’s interior.

The incident further shook public trust in military and civic authorities whose shared role it was to counter escalating displays of misdeeds and indiscipline.

There was even precedent for precaution. At the time of the Great War, the arrest of a drunken sailor on May 25, 1918, resulted in City Hall being besieged; then, on Feb. 18-19, 1919, a racially motivated mob rampaged through the streets after a returning war veteran abused a Chinese restaurateur.

The question was what could be done this time around?

Preparations for VE-Day had begun in September 1944 amid hope that the war would be over by Christmas.

A streetcar, set ablaze by rioters, burns on the evening of May 7, 1945. Despite the signs of trouble, Rear-Admiral Leonard W. Murray allowed sailors free rein on VE-Day.[Naval Museum of Halifax; Nova Scotia Archives/1981-412 10]

Municipal and military officials gathered for a series of meetings spanning several months, their collective goal to co-ordinate cele-bratory plans and, above all else, to ensure that jubilations couldn’t descend into violent unrest.

A committee was appointed to organize efforts, headed by Civil Defence Director Osborne R. Crowell. Other key figures involved in preparations included Mayor Allan MacDougall Butler (who succeeded Jack Lloyd in May 1945); Police Chief Judson Jeffrey Conrod; Captain C. Balfour, commanding officer of the local naval barracks; Lieutenant-Commander Reg Wood, who led the navy shore patrol; and Rear-Admiral Leonard W. Murray, commander-in-chief of the Canadian Northwest Atlantic Command, the only Canadian to preside over an Allied operational area.

Thanksgiving church services, remembrance ceremonies, military parades and firework displays were all agreed upon in due course. However, these genteel affairs were then combined with a slew of decisions that would prove fateful.

Committee chair Crowell focused less on arranging entertainment and more on curtailing boisterousness. Elsewhere, Chief Conrod met with the provincial liquor commission and, together, discussed whether alcohol-selling outlets should close on VE-Day, a measure ultimately adopted. Naval barracks commander Balfour, meanwhile, announced “open gangway,” meaning that naval ratings not on duty could join in the merrymaking at will.

Such perceived free rein was arguably aided by the navy shore patrol’s Wood, who intended for his men to stay in reserve to answer emergency calls in force rather than have them monitor the streets. This move was approved by Murray, who planned to curb arrests for fear of “a serious riot.”

The measures didn’t cease there. Soldiers and sailors were implicitly discouraged from participating in civic events, with Murray maintaining the belief that having wet canteens open could “go a long way towards keeping the crowds of service personnel off the streets where they might do harm.” Those who did venture farther afield would find 44 of 55 eateries and all 11 theatres closed on VE-Day, deemed a necessity by most establishment owners, despite some pleas to the contrary, after realizing that the stretched-thin police were ill-equipped to provide protection.

Whereas the Canadian Army and Royal Canadian Air Force imposed strict schedules and rules of conduct on their garrisons, the Royal Canadian Navy’s guidelines were comparatively lax. Nevertheless, it took more than a sailor’s presence to cultivate discontent.

Added to the spectre of anarchy was mayoral inexperience and, of course, the frayed nerves of a war still being fought in nearby waters until May 7, 1945.

The question now was whether the guardrails would hold.

It started as it was always meant to start.

Spilling into the streets for an impromptu party, Haligonians ignored dense fog and torrential rain to mark victory in Europe, even if VE-Day was earmarked for the following day, May 8. The clouds later parted as bunting sprouted from windows, flag masts and telephone poles, only amplifying the jovial atmos-phere throughout Halifax.

Mayor Butler declared the 7th a civic holiday before promptly removing his car from the area for “security reasons.” Though most service personnel remained on duty, more than 9,000 naval ratings were expected to join the evening festivities.

In the meantime, the planned shuttering of cinemas, cafés and restaurants went ahead. Liquor stores likewise closed, freeing bootleggers to charge a premium of $15 per two-bit bottle of rye. Plus, in accordance with the agreed-upon police policy, enforcers prepared to gather and respond to trouble in strength.

That trouble seemed almost negligible until 9 p.m. when the wet canteen at the primary naval barracks at HMCS Stadacona shut down. The site had been well stocked with 6,000 bottles of beer, and the drunk naval ratings now released into the streets sought new methods to sate their feisty mood.

What would appear then than one of the despised streetcars. The naval shore patrol’s Wood glimpsed the disturbance from a Stadacona window, mustered 30 officers and hurried to the scene. He discovered the tram had escaped with minor damage. But it was merely the beginning of an exceedingly long night.

On Citadel Hill’s eastern slope, a crowd of 15,000 marvelled at a two-hour fireworks display launched from Georges Island and naval vessels. During the quieter interludes, however, came the equally distinct din of smashing glass.

Sailors, joined by scores of civilians, ran amok through downtown Halifax. The naval ratings harassed streetcars along Barrington Street by disconnecting their electricity supply, leaving them stranded to the whims of well-lubricated mobs. Hundreds of rioters surrounded one tram, ejected its driver and passengers, shattered windows, tore out seats and attempted to topple it. They eventually set it ablaze.

The task of restoring order fell to a police squad driven to the scene by Constable Fred Nagle. His arrival did little except fuel greater chaos. Nagle himself sustained injuries when the mob flipped his vehicle, forcing all other passengers to make a hasty exit while he remained trapped. The officer watched in unbridled horror as a sailor set the police wagon on fire. Caught in an inferno, Nagle’s bids for freedom were prevented by an individual shoving him back into the car. Thankfully, if belatedly, another sailor saw sense and pulled him out.

The next target soon became the firefighters tackling the flames, as rioters hacked at water hoses with axes stolen from the fire truck. Perhaps fearing the onset of sobriety, the crowd then shifted its attention to plundering the liquor stores.

The outlet on Sackville Street was the first hit when three merchant mariners threw a flagpole through the plate-glass storefront. Two more shops, on Hollis and Buckingham streets, were looted around midnight. The overwhelmed police, powerless to halt proceedings, stared impotently as the horde of uniforms and civilian accomplices extricated thousands of wine, beer and spirit cases.

The pandemonium continued with a range of criminal acts, from robbing the Wallace Brothers’ shoe store to foiled efforts to dump Nagle’s gutted patrol wagon into the harbour. Finally, in the early hours of May 8, the disorder fizzled out.

But the worst was yet to come.

Memories of the Great War riots paled compared to what Haligonians confronted on their streets the next morning. Due to the lateness of the previous night’s events, many had been unaware of the destruction wrought. They saw it now.

The signs were everywhere: shattered glass, strewn merchandise, devastated storefronts, and the wretched stench of stale booze, vomit and charred wood. Then there were the perpetrators, some of whom lay drunk in the gutters. As such, legitimate concerns were raised about whether the scheduled VE-Day celebrations would provoke further unrest. Rear-Admiral Murray, who inexplicably hadn’t been informed about the previous evening’s rampage while it took place, had since been apprised of the situation. He determined that his sailors still deserved their day; they had fought for it.

Mob mentality began anew shortly after 1 p.m., when the naval barracks’ wet canteen ran dry, once again forcing naval ratings into the streets. The men first vented their frustration on the canteen itself, hurling bottles and rocks at its windows. They then shifted their focus to a tram on Barrington Street.

Hijacking the streetcar, nearly 150 intoxicated sailors clambered inside or perched outside, with the remainder of the throng following behind as it lumbered downtown. Their numbers were eventually augmented by personnel of the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service, civilians and even children. They joined in smashing windows en route before abandoning the wrecked tram.

Additional streetcars, liquor outlets and shops soon faced the same fate. But, perhaps the most significant misfortune befell Keith’s Brewery, when a thirsty, 4,000-strong horde descended on its Lower Water Street warehouse.

Despite having barricaded the gate, security couldn’t protect the complex’s entire perimeter. Two dozen rioters breached it, emboldening hundreds more to swarm through. Colonel Sidney Oland, the brewery’s owner, resolved himself to the path of least resistance, offering free cases of stock. The decision paid off as satisfied intruders left the business largely undamaged.

“This is to thank you for your service to your country,” remarked Oland in donating 118,566 bottles of beer to the swarm as it formed an orderly queue.

Drunkenness, theft and vandalism weren’t the only crimes and misdemeanours taking place throughout Halifax. At Cornwallis Park (since renamed), for instance, couples were engaged in public fornication. Elsewhere, sailors sold stolen liquor in a cemetery.

Yet, the band played on at the Garrison Grounds ceremony, where about 20,000 Haligonians gathered for the scheduled events. Murray, who attended the service, devised a plan for the parade’s 375 naval ratings to march downtown. There, they would assist the shore patrol and police in quelling the violence.

And it may have worked, too, had someone thought to tell the parade officer in charge. Instead, 100 peeled off from the march and joined the rioters.

To make matters worse, Chief Conrod neglected to order his own officers to stay on duty after their shifts ended. The accidental oversight meant that 40 men—an entire platoon’s worth—returned to their homes at 4 p.m.

Seaman Donald Albert Douglas, HMCS Cobalt’s 19-year-old sick berth attendant, wouldn’t receive the same luxury, having been tasked with erecting an emergency ward to treat the wounded. The sailor laid claim to a “clear conscience” amid the turmoil as his short-staffed team “worked like pack horses.”

At 7 p.m., Douglas and two assistants “who were nearly sober” commandeered an army ambulance and headed into Halifax. Weaving past shattered glass, the trio saw “shoes, boots, chesterfields, clothes, cash registers, pots, pans and nearly everything you could imagine on the street.”

Their first patient was unconscious after “someone had taken the jagged end of a broken bottle and just slashed his face to pieces.” The team had just heaved the man into the ambulance when a soldier approached and offered to drive.

Countless others—including naval ratings—likewise volunteered their services across the city, whether in quelling the riots or providing medical assistance.

Over the next few hours, Douglas’ mismatched band of helpers made repeated trips into Halifax and provided aid to dozens.

“I got one fellow,” he wrote later, “who had had a broken bottle shoved into his back and twisted till it made a hole.”

Enough was enough for civic and military authorities. Mayor Butler, who had proposed enacting martial law without success, and Murray, who had at last conceded that more needed to be done, declared VE-Day celebrations over at 6 p.m. and imposed an overdue curfew two hours later. Bolstered by shore patrol officers armed with 150 axe handles and an incoming army contingent from Debert, N.S., both leaders boarded a sound truck and, touring the streets, ordered everyone to return home or back to base.

The streets of a battered Halifax began to empty, perhaps due to the authoritative voices that bellowed through speakers—or perhaps because the rioters were all rioted out.

Regardless, it would be one hell of a hangover.

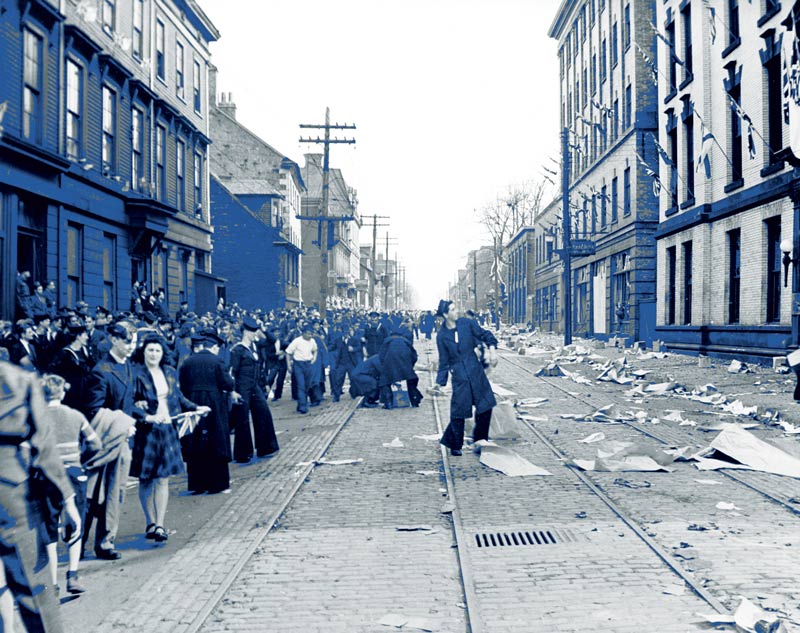

Service personnel and civilians alike walk past looted businesses in Halifax on VE-Day.[Naval Museum of Halifax]

“I’m ashamed that I’m in the Services and that I’m Canadian and I don’t mind telling you,” wrote a disillusioned Douglas to his parents on May 9, 1945.

Emotions were evidently high in the aftermath of the Halifax VE-Day riots, but one question was already at the fore: who was to blame?

Crammed into jail cells were masses of miscreants, 152 of whom had been arrested for drunkenness and another 211 for the likes of robbery, looting and possession of stolen goods. Those goods included 6,987 beer cases, 1,225 wine cases, and 55,392 spirit bottles from the liquor commission of Halifax; another 30,516 quarts of beer from Keith’s Brewery; and an additional 5,256 quarts of beer, 1,692 quarts of wine, and 9,816 spirit quarts from the commission in Dartmouth, where a smaller riot had occurred. Plus, 207 businesses pillaged and another 564 establishments damaged.

Were these imprisoned individuals the sole perpetrators of a destructive spree costing some $5 million? No, it would be deemed—it went higher than that.

Two people had died during the two chaotic days, while at least 29 sustained serious injuries, with many more minor ones.

Someone, surely, in the upper echelons of command would need to take responsibility for such casualties, not to mention the physical carnage.

That person became Rear-Admiral Murray, who, through a Royal Commission inquiry under Justice Roy Kellock—a militant teetotaler—endured an estimated 2,243 questions only to be later found at fault for virtually the entire debacle.

It was a view that corresponded with an ever-broadening consensus that sailors, who indeed comprised a sizable proportion of rioters, had mainly been left to their own devices while naval authorities and, therefore Murray, remained passive.

That was probably true to a certain degree, but the verdict failed to recognize the unique and unfortunate circumstances that made it possible. Civic authorities—from the municipal to the federal level—had done little to relieve pressures placed on overcrowded Halifax. The city’s military-civilian relationship was at an all-time low when the riots broke out—with Haligonians sharing a proportion of fault for that deterioration. And the fateful decisions, actions (and inactions) of others, be they in positions of power or simply on the streets, contributed to the disorder.

It mattered not: a scapegoat had been chosen.

An unrepentant Murray was relieved of command. With his hard-earned reputation forever tarnished—rightly or wrongly—the former rear-admiral committed himself to self-imposed exile in England, where he subsequently retrained to practise law. The renowned Battle of the Atlantic veteran died on Nov. 25, 1971, at age 75.

Halifax’s naval bonds were repaired with time. The heroic RCN response to the July 18-19, 1945, Bedford Magazine explosion did much to restore that relationship, with sailors playing a vital role in mitigating its impact. It almost certainly helped, too, that the city’s VJ-Day celebrations, when they at last occurred on Aug. 15, 1945, were a far quieter—and less riotous—affair.

Advertisement