Artillery crews man 60-pounders during the Battle of Amiens in August 1918. [DND/LAC/PA-002999]

The Hundred Days campaign was a series of battles unleashed by the Allied forces from Aug. 8, 1918, to the end of the war on the Western Front in France and Belgium on Nov. 11, 1918. They came on the heels of German offensives that started in March, marking a return to open warfare. In a half dozen slashing offensives, the Germans had penetrated the Allied lines, but they had not been able to break through. The 800,000 casualties suffered by Germany over four months of battle fell on the best trained and most aggressive combat formations. And now the Allies were ready to counterattack.

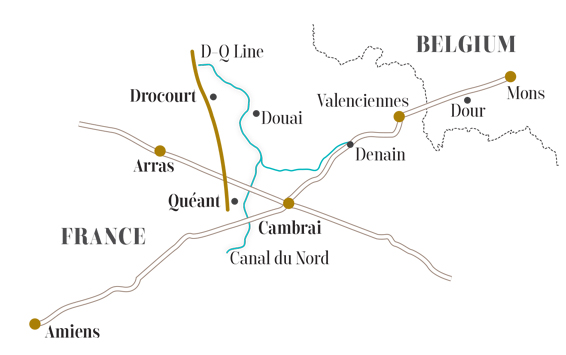

As part of the Allied offensive, co-ordinated by French General Ferdinand Foch, the British planned to strike to the east of the city of Amiens. Fourth Army commander Henry Rawlinson selected his two best fighting formations, the Australian Corps and the Canadian Corps, to spearhead the assault. Both units had proven themselves in battle.

The 100,000 Canadians who formed the Corps came from across Canada, from all regions, all classes and almost all religions. And they would fight, under Canadian-born Lieutenant-General Arthur Currie, through the Hundred Days campaign, starting at Amiens on Aug. 8 in a secret operation, moving northward to the Arras front for a series of battles against the Hindenburg Line from Aug. 26 to Sept. 2, and then to the crashing of the Canal du Nord and fierce fighting to capture the key logistical city of Cambrai in early October. A final push drove the Germans back to end the war on Nov. 11, 1918, with the capture of Mons. These titanic battles saw the Canadian Corps punch far above its weight, leading crucial attacks, meeting and defeating elements of more than 50 German divisions, and forging a reputation as an elite fighting force.

The following experiences of four Canadian infantrymen offer a glimpse into the bewildering world of battle during the Hundred Days campaign.

Canadian machine-gunners in armoured cars go into action during the Battle of Amiens. [DND/LAC/PA-003016]

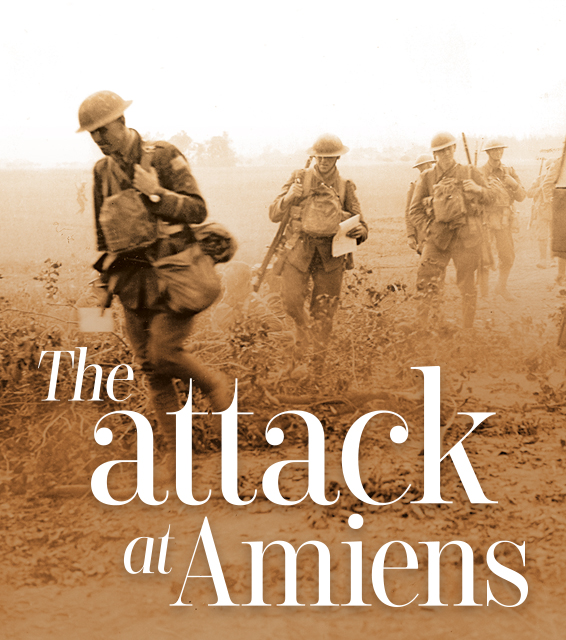

Part of the excitement was that the infantry could see camouflaged ammunition and shell dumps behind the lines, as well as hundreds of tanks that lay hidden in the wooded areas. Above the battlefield, overwhelming numbers of French and British planes, numbering some 2,100, circled the skies to ensure that enemy planes did not discover the assault.

At 4:20 a.m., the guns roared to life and “a great flash filled the skies and immediately the greatest roar I had ever heard or ever expect to hear again struck my eardrums,” recounted Becker. Allied artillery overwhelmed the enemy guns, at least initially, and the first waves of Canadian infantry set off behind a fast-moving creeping barrage, supported by 168 Mark V and lighter Whippet tanks.

Becker’s 75th was part of the secondary wave of attackers in the 4th Canadian Division, which was to drive forward after noon—across unharvested wheat fields and around the recently slain—and keep up the momentum of the attack. Becker and his mates were amazed by the tanks that had flattened wire and overrun stubborn German machine-gun nests. But while the tanks were largely bulletproof, they were susceptible to the German artillery that aimed directly at tanks and anti-tank rifles that fired 13-millimetre armour-piercing rounds.

“We passed two large tanks that had met direct hits and were blazing merrily,” recalled Becker. Black smoke rose into the clear summer sky and the smell of roasting flesh caused men to gag. “The crews were probably burning to a crisp inside.”

The 75th’s objective was Le Quesnel, a small village with a tall church, on the Canadian Corps’ southern sector. The flat killing ground over which the 75th had to advance had few trees and little cover.

Two companies assaulted at 3:20 p.m. The Germans immediately opened up with their Mauser rifles and MG 08 heavy machine guns. “Watching the small parties advancing, we could see men drop and fail to get up,” recounted Becker, whose company was laying down supporting fire.

As the attack went to ground, ‘D’ Company was thrown into the cauldron of battle and Becker led a section of rifle grenadiers forward. They advanced in short rushes, running 10 to 15 metres before diving for what little cover they could find when the enemy guns turned on them.

“Machine-gun bullets cracked and whipped around us,” recounted Becker, “Dirt flew and the shortgrass was clipped and thrown over us.”

As they closed the distance, a shell detonated near Becker, just as a bullet struck him. He later remembered that he felt like “a mule or something very similar kicked me a jolt that jarred my carcass from stem to stern.” He knew he was hit, but not how bad or by what.

A stretcher-bearer rushed to his aid and patted him down, eventually determining that the injury was to his shoulder, which was badly broken and bleeding from a bullet. As the stretcher-bearer was working on him, a Canadian private stumbled over to them, having been shot in the face. “A bullet had apparently gone in one cheek and out the other and he was spitting teeth with foundations of gore,” recalled Becker.

Becker told the medic to focus on the private with the ruined face and stumbled back to the rear, his shoulder bandage seeping red. He was one of the many walking wounded dragging themselves from the fire zone to medical aid. Indiscriminate shells and bullets had no mercy for the vulnerable wounded, and some of them were struck down again.

The 75th took Le Quesnel, but not until a second assault in the early hours of the next day and at the cost of 133 officers and men killed or wounded.

“We were all just kids,” said Becker, whose war ended at Amiens. “But every kid could be depended on to the last round of ammunition and the last bomb.” These kids, new recruits and battle-hardened soldiers, were the ones who won the Battle of Amiens.

Canadian troops advance behind a barrage during the Battle of Arras. [William Rider-Rider/DND/LAC/PA-003145]

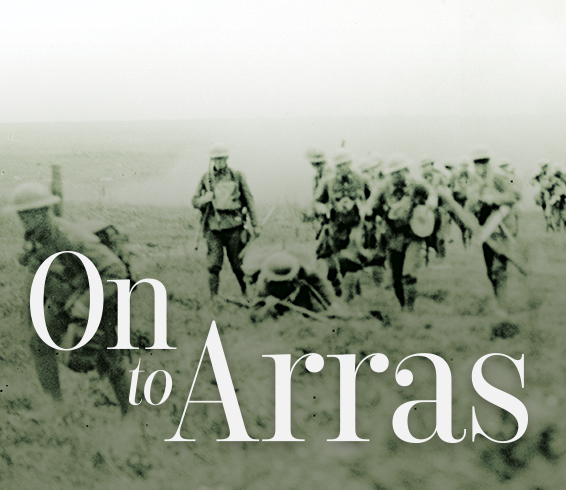

The Canadians suffered almost 12,000 casualties. They were then moved to the Arras front for another major battle, this time to lead the assault for the British First Army.

Close to the front was Cpl. Deward Barnes of the 19th Battalion. A handsome man with a trim moustache, Deward had enlisted in Toronto in February 1916. His baptism of fire had come in May 1917, in the aftermath of the Vimy victory, and he had fought through the great battles at Hill 70, Passchendaele and Amiens.

Currie ordered a 3 a.m. zero hour in the hope that an early attack might buy a bit of time for the gunners to lay down a withering bombardment and silence, if temporarily, enemy batteries that were set to lob shells into the advancing infantry. The first waves of troops attacked on Aug. 26 and made good progress, but the fighting was hard and the 19th was kept in reserve until the next day.

On Aug. 27, the 19th was thrown into battle at 10 a.m., advancing through swampy fields near the Sensée River. With surprise lost, the Germans were ready.

“Those machine guns of his played havoc with us,” wrote Barnes. “We got nearly to our objective, but could not make it.” With dozens of soldiers left writhing in no man’s land, the survivors dug in to a dry river bank and took a pounding from German artillery shells. The Canadians toughed it out, and attacked again the next day, even though most of the infantry battalions were shot up and worn out.

The 19th’s attack in the early afternoon on Aug. 28 made little progress. “Held up by machine guns,” Barnes wrote laconically. At this point, almost all the officers were dead and wounded and, incredibly, Barnes was left to command the remnants of two platoons.

The Germans attacked later in the afternoon, but the 19th survived the assault, and even struck back in the violent see-saw fighting. The much-weakened battalion encountered another machine gun sweeping the front, protected by deep rows of uncut barbed wire. There was one gap in the barrier and the infantry, in the chaos of fighting, were drawn to the opening with disastrous results. “There must have been 40 men all heaped up dead in that gap,” wrote a horrified Barnes.

The 19th’s attack failed, as did many that day for the Canadian Corps, although much of the trench system was captured. The two divisions that assaulted from Aug. 26 to 28 suffered almost 5,800 casualties, of which some 285 were officers and privates of the 19th.

Barnes and the survivors limped out of the line, although he continued to fight until his war ended on Oct. 11, 1918, a month before the Armistice. In fierce combat near Iwuy, a bullet struck him through the right thigh, passing through his buttock. It was a good wound—a Blighty wound, as the soldiers called it—and he would spend weeks recovering in a hospital far from the fighting.

After the three days of fierce fighting from Aug. 26 to 28, Currie ordered a pause and the Corps regrouped for another assault on the Drocourt-Quéant Line, one of the most formidable positions on the Western Front. The Canadians hurled tens of thousands of shells at the multiple trench lines, aiming to clear the barbed wire and smash the concrete pillboxes that housed machine guns. Fresh Canadian infantry units were rotated to the front for this major assault.

Lieutenant George McKean was a scout officer with the 14th Battalion, and he organized the secret shuffle of his battalion to the front lines. The British-born McKean was an enthusiastic hero of the trenches who had spent much of the war since arriving at the front in June 1916 patrolling no man’s land—which he called a “hunting ground.”

McKean was awarded the Military Medal for bravery when he was a non-commissioned officer and then, after being commissioned as an officer, he received the Victoria Cross for a daring nighttime raid in the early hours of April 28, 1918. McKean led the assault, rallied his troops, and attacked large groups of enemy soldiers alone in a mad melee of combat. His audacious action resulted in knocking out an enemy machine gun and capturing and killing German soldiers.

McKean continued his fearless exposure to danger in the Battle of Amiens and at Arras, scouting the front and organizing attacks on the enemy lines in what he called “attack followed upon attack.” Amid shellfire and much “dirty business,” in the early hours of Sept. 1, McKean led a bayonet charge on an enemy position known as the Crow’s Nest to clear it before the major assault the next day.

“A solitary machine gun spat for a few seconds, and two or three bombs were thrown from the trench, and then we were on top of them! The Huns made a brief effort at resistance, but it was short-lived. Then they shrieked for mercy—but it was too late!” Eight machine guns were captured, with most of the gunners killed.

McKean was not yet done. He thrived in the maelstrom of battle. The next day, Sept. 2, the Canadian guns laid down a crushing barrage as thousands of Canadians, supported by British soldiers, surged ahead in the assault on the D-Q Line.

In pressing forward, the 14th was scattered and shot up, and the enemy shellfire claimed men all around McKean. After more than two years at the front, his luck finally ran out. A heavy 5.9-inch shell landed among a group of 15 soldiers huddled in a large crater as they prepared to strike into Cagnicourt, a German-fortified village blocking their advance.

“I felt something hot, for all the world like a hot cinder, go into my leg, and I knew I was hit,” recalled McKean. “The scout corporal who was with me fell on his face, killed instantly.”

When the smoke cleared, about half were down, with men screaming and moaning. McKean was left with eight men and a Lewis gun and despite bleeding freely, he saw that the German defenders in Cagnicourt had taken refuge in cellars and dugouts to escape the shellfire. Their guns were unmanned, but only temporarily.

Seizing the moment, McKean led an attack, with the nine men charging forward against an enemy force that likely numbered several hundred Germans. The Canadians ran and hobbled, shooting surprised German sentries and catching most of the defenders in their dugouts. Dozens and then hundreds of Germans exited from their positions, arms raised, shocked to find that the Canadians who had snatched the village were fewer than a dozen in number. Cagnicourt fell to McKean and his brave group, and all along the line hundreds of individual battles and clashes left the Germans in retreat.

McKean’s wound was bad enough to evacuate him from the front and he did not return to his unit until after the Armistice. He was awarded the Military Cross for his gallantry at Cagnicourt, and he might very well have been recommended for a second Victoria Cross. But perhaps he earned something better, writting, “I limped painfully out of the war with the feeling that a triumphant ending was fast approaching.

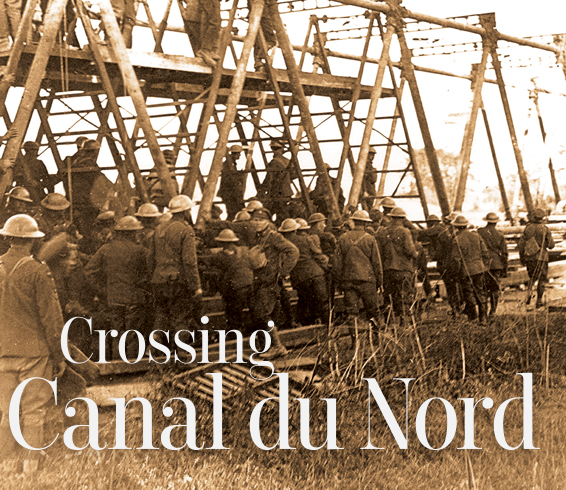

Canadian engineers build a bridge to cross the Canal du Nord, east of Arras. [DND/LAC/PA-003456]

The canal was about 30 metres across and fiercely guarded on the eastern banks. Behind it was a series of thick trench systems that protected the all-important logistical city of Cambrai. The Germans could not retreat from this sector as it was their last significant line of defence. Units were ordered to fight to the last bullet.

Currie ordered an audacious, even dangerous, plan of crossing the canal at one of the few dry spots, pushing his large corps through an opening about 2.6 kilometres wide then fanning out on the other side. If the Germans repulsed the lead Canadian units, clogging up the canal, the traffic jam of humanity and horses leading back from the front would be ripe for slaughter from enemy artillery.

But the soldiers at the front knew little of the plan. They were focused on the two or three hundred metres in front of them.

Lieut. Charles Henry Savage, who had enlisted at Sherbrooke, Que., was serving with the 5th Canadian Mounted Rifles. The 26-year-old clean-shaven, pre-war teacher had been wounded on the Somme in October 1916 and returned to his unit in early 1918. So far, he had survived the battles at Amiens and Arras when so many of his comrades had not.

The attack went in on Sept. 27, with the 1st and 4th divisions crashing the Canal du Nord and pushing eastward. Behind them and under fire, Canadian engineers laid bridges for trucks, horses and artillery, while footpaths were erected over some of the wet spots for the infantry. The Germans were driven back, but there was intense combat until Oct. 1 in what Savage described as “the most deadly fighting the Canadians ever took part in.”

After a pause that lasted for a week but still saw an active front of trench raids and small-unit operations, the 5th CMR marched forward with other units over the captured terrain to prepare for the final assault against Cambrai on the night of Oct. 8.

When they set off late on Oct. 8, the 5th CMR moved from the farmers’ fields on the outskirts of Cambrai to urban warfare. The German defence crumbled under the assault and the enemy pulled back. But first they tried to burn down the city and make it unusable for the Allied forces.

German rearguard forces including snipers and machine-gunners took a toll on the Canadians, but they were slowly snuffed out during the early hours of Oct. 9, usually with prodigious use of grenades. In one of these patrols, Savage was caught in the open as two machine guns raked the streets.

“There was nothing to do but run,” he recalled, and so he set off, eventually finding some cover behind a narrow telephone pole that did not cover his entire body. “I stuck out on both sides of the pole, but most of my vulnerable parts seemed to be protected so I made myself small.”

Bullets thudded into the wood pole and one knocked off his steel helmet. He felt his luck had run out, especially when he noticed that the bullets were passing through the eight inches of wood that he prayed would protect him. He set off in a desperate run and dove for cover before bullets cut him down.

The Germans began their full-scale retreat after Cambrai was captured. “It was a death struggle and both sides fought desperately,” Savage recounted.

The final month of the war saw the Canadians still spearheading First British Army as they chased down the enemy. All along the front, dozens of French villages and towns were freed from the clutches of the Germans who had occupied this area since the early part of the war. The Canadians were joyfully greeted as the liberators that they were, but that excitement was tempered by anxiety over the fear of being the last man to die.

Savage was again on the front lines early on Nov. 11, studying a map, preparing to make a push beyond Mons, which had been overrun by the Canadians earlier in the day. That symbolic city was where the British army had begun its retreat in August 1914. Its capture brought further glory to the Canadians. But still the fighting seemed destined to go on, even though rumours swirled that the war might soon end.

A little before 11 a.m., Savage was planning a new push forward, an assault where he knew men would be killed or maimed. He barely looked up when one of the privates came in and quietly told him, “as if he were telling me that breakfast was ready, ‘The war is finished.’”

Savage, like most of the Canadians, was stunned by the news. There were few celebrations among the infantry at the front, although deep relief soon set in. Everyone was alone with his thoughts and the slow realization that they had survived the final push.

Barnes, who spent Nov. 11, 1918, in a hospital, reflected in his diary about his original Lewis gun section of seven pals: one was killed at Hill 70 in August 1917; another at Passchendaele in November that year; and a third “went west” in early October 1918; another was shot through the lung; another gassed and a third listed as “sick,” which may have been shell shock. Most of his close friends never made it home.

It was the same for Becker, McKean and Savage, all of whom lost their chums and bore their scars, physical and mental, men made old before their time. The survivors set off into the postwar world wondering what they would do for the rest of their lives.

Advertisement