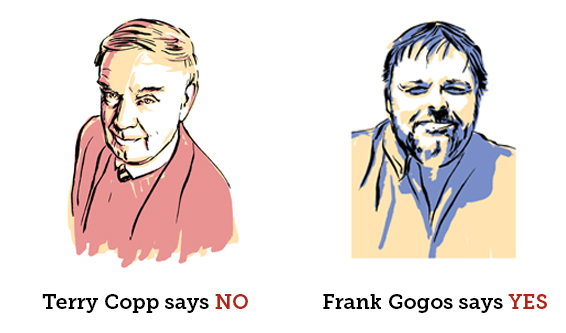

Terry Copp Says No

Historians often rely on hindsight to determine what questions are worth asking. Since we know the tragic results of Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Hadow’s orders, we naturally want to know why he sent the Newfoundland Regiment forward on July 1, 1916. Hindsight won’t help us answer the question. Instead, we need to learn what Hadow knew when he made the decision and what he might have reasonably inferred from what was known.

Hadow, a British regular army officer, was appointed to command the Newfoundland Regiment during the last phase of the campaign in Gallipoli. His stiff manner, masking the insecurity of a staff officer asked to command an infantry battalion, initially won him few friends, but over time he learned to lead as well as command.

When VIII Corps commander Lieutenant-General Aylmer Hunter-Weston received his orders—which called for the capture of the first and second German positions on the first day—he told Fourth Army commander General Henry Rawlinson that “everyone was strongly opposed to a wild rush for an objective 4,000 yards away.” He warned against “losing the substance by grasping at shadows.” Rawlinson agreed. He had proposed a “bite and hold” plan, focused on securing the enemy’s first position then pausing before a further advance. Commander-in-Chief Sir Douglas Haig had rejected this plan as “too cautious.” Haig wanted a breakthrough, not an attritional battle.

Hunter-Weston obeyed orders, instructing the 29th Division to use battalions from the 86th and 87th brigades to move up to the German wire by 7:30 a.m.—zero hour—and advance in turn according to a timed schedule. The 88th Brigade, including the Newfoundland Regiment, was to move off an hour later to attack the Germans’ second position, 3,000 metres away.

The decision to blow the mine under Hawthorn Ridge at 7:20 gave the enemy warning and time to reach the lip of the crater before the British. The advance slowed as the troops discovered there were too few gaps in the German wire. Then the timed barrage moved on, leaving the men exposed to relentless fire.

Hadow would not

disobey orders, but

he did question them.

The Newfoundlanders and their sister battalion, the Essex Regiment, waited in reserve trenches. They could hear the battle, but no information was getting back. At 8:20, Hadow was ordered to “advance and occupy the first system of trenches,” a very different objective than the one they had prepared for. Hadow was a professional soldier. He would not disobey orders, but he did question them. “Has the enemy’s front line been captured?” he asked.

Brigadier-General Douglas E. Cayley, commander of the 88th Brigade, knew little more than Hadow. He believed that the lead brigades were fighting in the enemy trenches and needed support. Cayley told Hadow that “the situation had not been cleared up,” so the Newfoundland Regiment should attack “as soon as possible” independently of the Essex Regiment. There was nothing more Hadow could do. He briefed his company commanders and at 9:15, the advance into the inferno began.

It was all over in less than an hour. At Beaumont-Hamel, as elsewhere on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, responsibility for the disaster rested with one man: Haig. His plan of attack—limiting the artillery available to attack the first position so that the second position could be hit—indeed meant “losing the substance by grasping at shadows.”

Frank Gogos says YES

When Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Hadow ordered his men of the Newfoundland Regiment over the top near Beaumont-Hamel on July 1, 1916, he unwittingly unleashed a maelstrom of controversy that has yet to subside. To his naysayers, he is often seen as a typical British officer who had little regard for the safety of his men. They heap a large part of the blame for the Newfoundland casualties on Hadow and the British system that produced him.

Hadow could hardly be blamed for the carnage that happened on the Somme on July 1. That blame lay at the feet of officers much more senior than him. But did his decision to advance from the reserve trenches inadvertently lead to more casualties to the Newfoundland Regiment?

When the 88th Brigade commanders gave the order to attack at 8:45 a.m., Hadow asked if he was to attack independently of the Essex Regiment’s 1st Battalion, to which the reply was yes. The same order was given to the Essex at the same time. The 88th Brigade had ordered both battalions to attack when ready. The commander of the Essex chose to move through the reserve and communications trenches to get into position at the front line, which took them two hours to complete.

Hadow, realizing that he could not get his men to the front line without a great delay, ordered them to launch their attack from the reserve trenches some 200 metres or more behind the front line. It took 30 minutes for Hadow to relay the new objectives to his company commanders and launch the assault at 9:15 a.m.

Was Hadow following strict orders to proceed from the reserve trenches, or could he have done what the Essex had done and move through the carnage in the communication trenches and line up in the firing line before the advance?

The answer is that there was no direct order to advance from the St. John’s Road reserve trenches. That was Hadow’s interpretation of the order to attack.

But did this decision by Hadow lead to more casualties?

The answer to that is less clear. The delay that would have resulted by moving the Newfoundlanders to the front line might have helped curtail the massive casualties. On the surface, the fact that the Essex’s casualties were far fewer than the Newfoundland’s was a result of the Essex’s delay. And when the Essex did go over the top, they did not advance far before the order to cease the attack reached them. Nobody else advanced during or after the Newfoundlanders’ attack. But if the Newfoundlanders and the Essex had attacked side by side, it may well have resulted in similar casualties for both battalions. The only difference is that we would not be debating Hadow’s decision.

Hadow’s decision to

launch from the reserve

lines makes little sense.

If the Newfoundland Regiment had not gone over when it did, however, there would have been no basis for Brigadier-General Cayley to rescind the order of a follow-up attack after Hadow voiced his concerns to a 29th Division staff officer.

Hadow’s only explanation for his decision to attack from the reserve trenches was because of the dead and wounded choking the trenches. As a result of his decision, many men fell before reaching their own firing line. It did ultimately lessen the casualties to the Essex.

Hadow’s decision to launch from the reserve lines makes little sense, but he should not be judged by this decision alone. The real culprit for poor decision making in this sector lands squarely at the feet of brigade and divisional command, as there were serious communication breakdowns that led to Hadow’s confusion, and delays in countermanding a subsequent attack before the Essex got a portion of their men over the top.

Terry Copp, a frequent contributor to Legion Magazine, is director emeritus of the Laurier Centre for Military and Strategic Disarmament Studies at Wilfrid Laurier University. He is the author of numerous books and articles on Canada’s role in the two world wars.

Frank Gogos is chair of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment Museum and the author of The Royal Newfoundland Regiment in the Great War: A Guide to the Battlefields and Memorials of France, Belgium, and Gallipoli.

Advertisement

Related posts:

Face To Face: Was Vimy Ridge the Canadian Corps’ greatest victory?

Face To Face: Was the liberation of the Netherlands the Canadian Army’s most important achievement in the Second World War?

Face to face: Is it time to redesign and replace the Canadian Army’s combat uniform?

Should Canada have gone to war in September 1939?