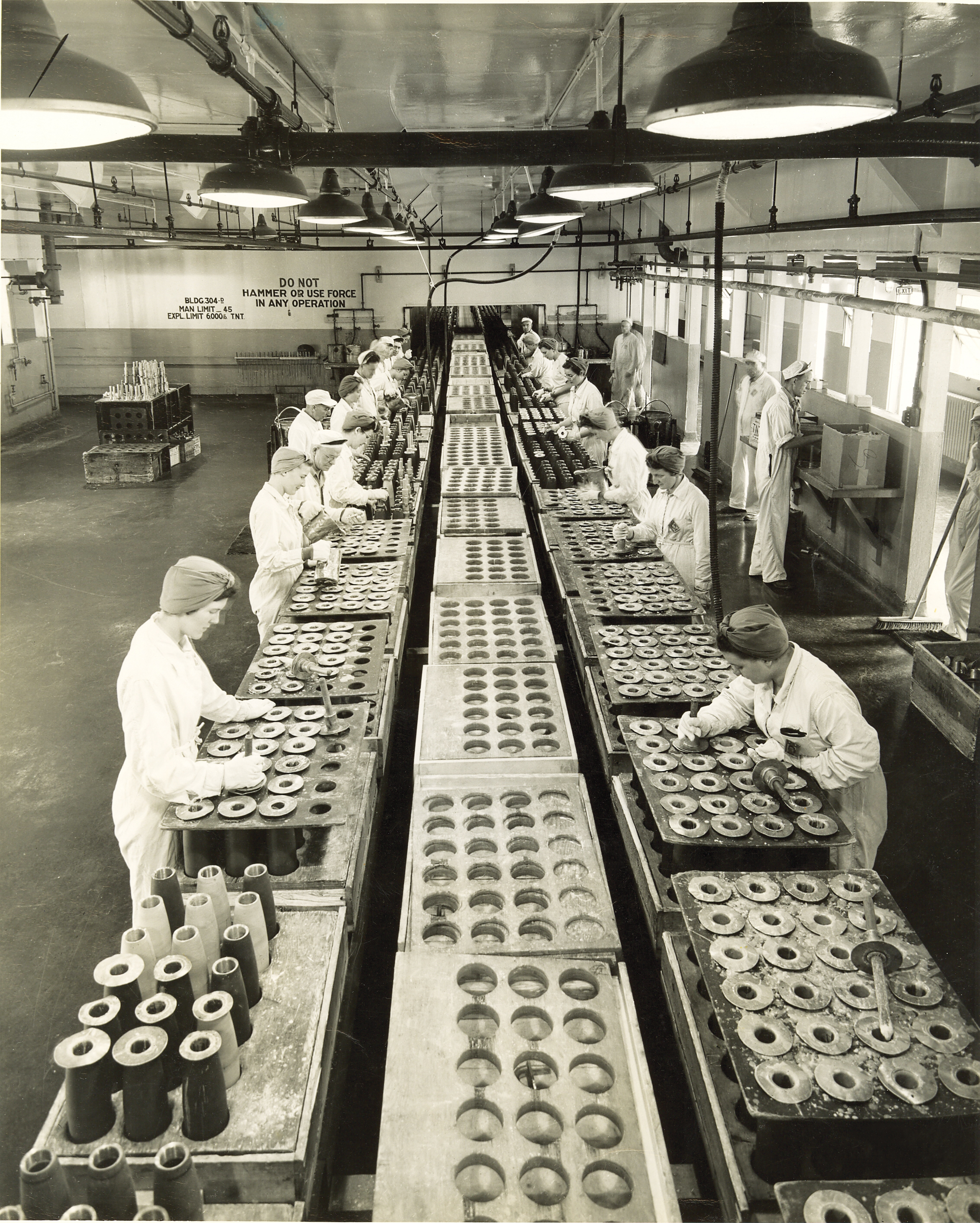

Dressed for work: Women had to remove bobby pins and put their hair up in bandanas while working on munitions. [Ajax Archives/Town of Ajax]

During the Second World War,

more than 2,300 women from across Canada

were recruited to work in the

DIL munitions factory

When Louise Johnson got the call to contribute to Canada’s war effort in November 1942, she accepted immediately and never looked back or regretted her decision. The former Saskatchewan farm girl was 18 and working at Saskatoon City Hospital when she was recruited for wartime duty at the huge Defence Industries Limited (DIL) munitions complex in Pickering Township, then a predominantly rural municipality 40 kilometres east of Toronto.

After passing medical and physical examinations and clearing a police background check, Johnson boarded an eastbound train with some 300 other young women. Everyone received a blanket and a pillow and slept in their seats for three nights—there were no berths on their coach cars. When they arrived at Toronto’s Union Station, they piled onto buses that shuttled them to the DIL complex.

Nine thousand men and women worked there at the peak of production. DIL recruited some 2,350 women from the Prairie provinces, the Maritimes and various parts of Ontario. Most of the men served as managers, administrators, foremen or supervisors while the women worked the assembly lines. Their jobs could be dangerous, as well as repetitive to the point of being monotonous.

They handled TNT, amatol and RDX (a military explosive known as Research Department Formula X) day in, day out and, among other things, they filled percussion caps, detonators, small bombs, anti-tank mines, armour-piercing artillery and anti-aircraft shells. Production of caps and detonators began in July 1941 and by the end of the war, the men and women of DIL had produced more than 51 million units of heavy ammunition and nearly 234 million caps, detonators and pellets.

But that was far from the end of the story. A town called Ajax arose on the site of the former munitions complex and today it is a flourishing suburban community with a population exceeding 100,000. The women of DIL were part of the inspiration for the hit series Bomb Girls, which ran on the Global Television Network in 2012 and 2013.

And Louise Johnson was there to witness it all. She married Russel Johnson, a fellow DIL worker, made her home in Ajax and has shared her wartime memories with many people over the years, including local historians and the creators of the Bomb Girls series. “We considered ourselves part of the war,” says 91-year-old Johnson. “We knew our importance. If the boys didn’t have shells, they couldn’t win the war. No one missed a shift unless they absolutely had to. Absenteeism just didn’t exist.”

Assembly line : A worker looks through the artillery shells at the DIL plant in Ajax, Ont. [Ajax Archives/Town of Ajax]

Britain turned to Canada for munitions in the grim, early days of the war, when the German Luftwaffe was flying across the English Channel with impunity, bombing London and other cities and inflicting grave damage on the country’s manufacturing infrastructure. Several munitions plants were established on Canadian soil, including the General Engineering Company of Canada, which was just beyond the northern limits of Toronto, and served as the template for the Bomb Girls series.

25 million: DIL employees gather by the gatehouse to celebrate the 25 millionth shell produced at the plant. [Ajax Archives/Town of Ajax]

The DIL plant was the biggest complex in this country and, for that matter, the entire British Commonwealth. Shortly after the start of the war, the federal government expropriated almost 12 square kilometres of farmland extending from the shore of Lake Ontario north to the Canadian National Railway main line. Its freight trains delivered raw materials and picked up finished munitions to start the journey to embattled England.

“We knew our importance.

If the boys didn’t have shells,

they couldn’t win the war.”

Government surveyors arrived on the property in February 1940. Construction crews went to work in early 1941 and the entire complex was complete by the end of that year—and it was a monumental undertaking. There were nearly 50 kilometres of railway spur lines on the site and 50 kilometres of roadways. There were four shell-filling lines and a pellet and tracer line, all located in separate buildings, as well as warehouses for storing shell casings and explosives. Ammunition magazines, covered on three sides with mounds of earth, were located on the south end of the property along the lakeshore.

A water treatment plant capable of processing almost four million litres a day and a sewage treatment plant were built at the waterfront. Administration buildings were located in the northeast corner, adjacent to the CN line. Twenty-one dormitories with semi-private rooms were erected to accommodate the women and a smaller number for men, since there were usually twice as many female as male employees on site. There was also a large cafeteria, a commissary, a recreation centre, a social centre that served as a place of worship on Sundays and a 32-bed hospital staffed by five doctors and 15 nurses. To eliminate the possibility of sabotage, a 2.5-metre chain link fence, topped by three strands of barbed wire, surrounded the property and armed guards in towers monitored the perimeter 24 hours a day.

After all that, one problem remained—how to accommodate the married workers who lived or boarded in nearby communities and found transportation difficult since automobile ownership was a wartime luxury and public transit was non-existent. The government resolved the issue by building 600 two-bedroom, basement-less bungalows between the CN line and Highway 2, then the main road between Toronto and Kingston.

Employees worked three shifts a day, six days a week and earned 50 to 80 cents an hour, which was better than the typical wages at the time. Safety was a top priority. All the food in the cafeteria was steamed rather than grilled, fried or baked to reduce the risk of a fire that could trigger explosions. Anyone caught with cigarettes, lighters or matches could be fined, fired or even jailed.

“The production lines were squeaky clean,” says Johnson. “You wouldn’t find a dust bunny anywhere. You had to change from your street clothes and put on uniforms and you had to wear special-issue shoes before going into a designated clean area.”

Star visitor: Actress Mary Pickford visits the Defence Industries Limited plant. [Ajax Archives/Town of Ajax]

The soles of the shoes were leather, stitched rather than stapled since staples might cause sparks and an explosion. The women had to take off wedding rings, or cover them with tape and they had to remove bobby pins and fasten their hair with bandanas. Nevertheless, accidents were inevitable. Three workers died in explosions, says Brenda Kriz, archivist for the town of Ajax, and many women lost fingers or fingertips to explosions.

There were Tuesday evening square dances and Friday night dances with big bands and young men from Whitby, Oshawa and other nearby communities which more than compensated for the shortage of males on site. There were movie nights and a library and the athletically inclined could play baseball, basketball, badminton or tennis.

Letters to and from loved ones—either soldiers fighting overseas or families back home—were indispensable wartime morale boosters and the volume of DIL mail quickly overwhelmed the tiny post office in Pickering Village. In the summer of 1941, says Kriz, the administration concluded that the complex needed its own postal station and asked employees to submit names.

The suggestions included Dilco, Dilville, Powder City and Ajax—the latter being the name of the British battleship that led HMS Achilles and Exeter in a transatlantic pursuit of Nazi Germany’s Admiral Graf Spee. The chase ended with the Graf Spee trapped in neutral waters at the mouth of the River Plate, near Montevideo, Uruguay, in early December 1939. Rather than fight and lose, the German captain scuttled the ship on direct orders from Hitler. It was an uplifting victory and the managers at Defence Industries commemorated it by naming their postal station after the HMS Ajax. The name was retained for the new municipality that rose on the site of the DIL complex.

After the war, the shell-filling lines, explosives warehouses and many other structures were burned because they were contaminated with residue of TNT, amatol and other volatile substances. Several miles of railway spur lines were lifted and the lakefront magazines flattened. The administration buildings were put to civilian use as University of Toronto classrooms for engineering students and the women’s residences as short-term shelter for European refugees. The government intended to demolish the 600 wartime homes, but post-war housing shortages derailed that plan.

Instead, the government offered them to Pickering Township, but the township council said no thanks—it couldn’t afford to provide the services required—so Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) took possession and sold them to the occupants.

In 1950, CMHC established the Ajax Improvement District and set up a three-member board of trustees to lay the foundations of a civic administration and, five years later, the provincial government approved the incorporation of the town of Ajax. The new municipality grew slowly through the 1960s and 1970s, but has experienced explosive growth over the past 30 years.

“I’ve watched Ajax grow through the decades,” says Johnson, who bought one of the wartime houses in 1951 with her late husband and continues to reside there. “It’s overwhelming, really.”

Advertisement