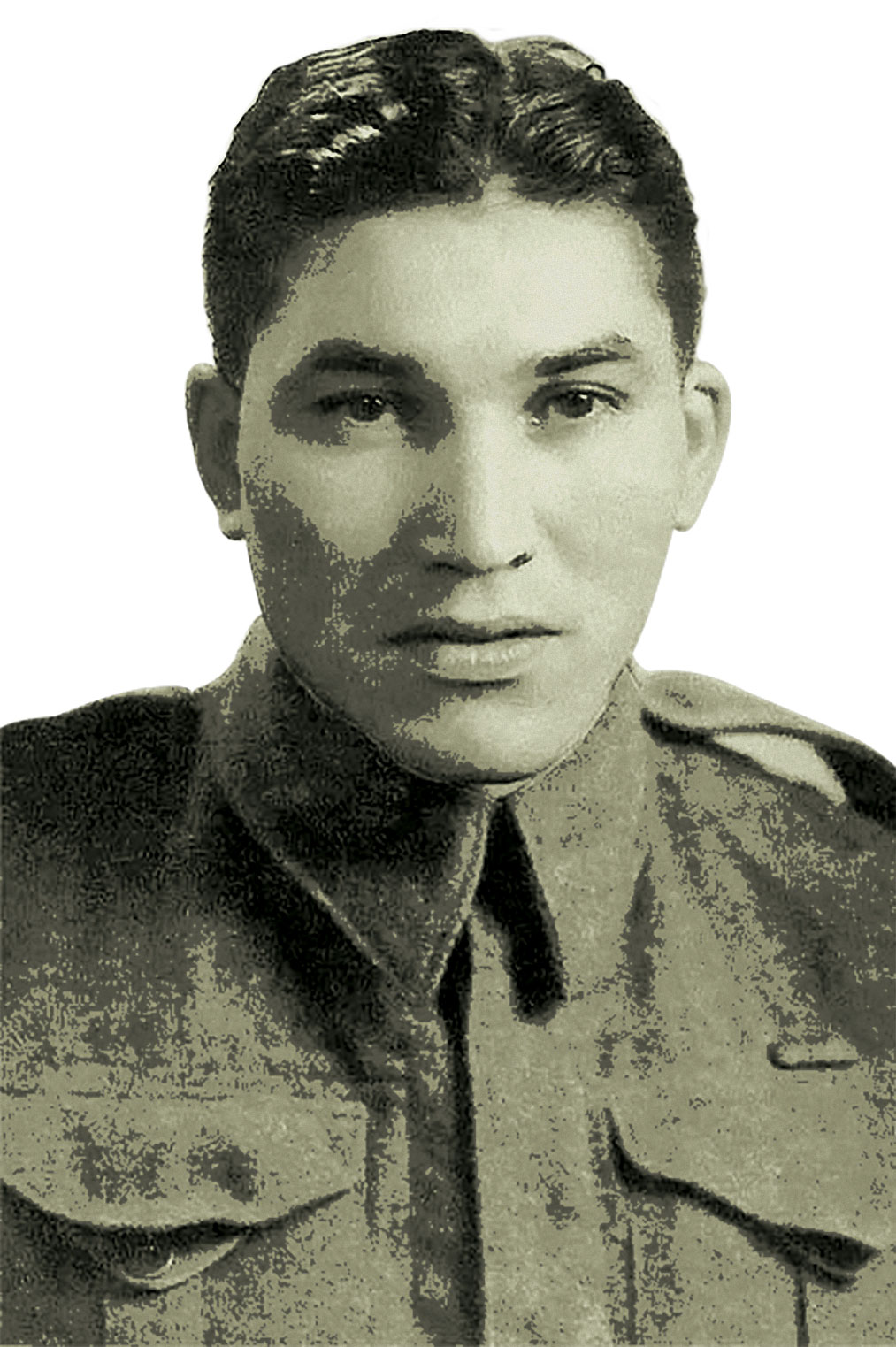

Charles (Checker) Tomkins. [Shirley Anderson / The Canadian Encyclopedia]

For two years during the Second World War, Charles (Checker) Tomkins, a Métis from Grouard, Alta., was given a secret assignment. It was a secret he very nearly took to his grave, an Indigenous contribution to the war effort almost lost to history.

Tomkins learned Cree from his parents and grandparents. He enlisted in 1939, trained and was sent overseas where he was assigned to the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade.

In 1942, he received a mysterious summons to headquarters. When he arrived, the room was full of Indigenous soldiers who were put into different rooms, connected by telephone, and given messages to translate to and from English and Cree.

Tomkins became a Cree code talker, seconded to the American air force and charged with coding and decoding secret messages that would baffle and befuddle the enemy if intercepted.

Not much is known about the code talkers from Canada, who or how many they were, how their work contributed to victory. They were sworn to secrecy and after the war dispersed back into their communities, often remote; most never learned that they were released from that vow in 1963.

Charles (Checker) Tomkins (second from right) kept secret his job as a Cree code talker, even from his four brothers (from left) John Smith, Henry, Peter and Frank Tomkins, who also served. [The Canadian Encyclopedia/Memory Project/Historica Canada]

Information about orders, troop movements and supply lines, bombing runs, enemy movement and other intelligence were translated into Cree at one end of the communication line, and into English at the other.

The messengers had to be highly creative, for many military words—tank, bomber, machine gun—were not in the Cree lexicon. Code talkers adapted other words to their purposes: the Cree words for wild horse, fire, bee and the number 17 identified Mustang aircraft, Spitfires and B-17 bombers.

Tomkins never divulged his secret assignment, not even to his four brothers who also served, until he was 85. Just months before his death, he told his story in an interview with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

“I love my country and I’ve done everything they asked me to do,” he said.

Tomkins was one of thousands of Indigenous people to answer the call after the Second World War was declared. About 3,100 Status Indians enlisted, including 72 women. As with the previous war, no one knows how many other First Nations, Métis and Inuit signed up with the Canadian forces, nor how many from reserves near the southern border served with American forces, wrote Janice Summerby in Native Soldiers, Foreign Battlefields. Indigenous volunteers made up a large proportion of Canada’s 15,000 Pacific Coast Militia Rangers, formed after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

As in the First World War, Indigenous people were divided in their support. Some argued they were exempt due to their status under the Indian Act or various treaties. Others were influenced by experiences after the First World War when, despite stellar service, Status Indians did not secure equal access to veterans’ benefits, nor did they retain the right to vote once they took off their uniforms.

Some were angered that Status Indians were not initially exempt from conscription. Some just thought a war in Europe was none of their business. But others were in full support. All but three of the eligible men from the Algonquins of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation (formerly Golden Lake First Nation) in eastern Ontario signed up.

Motivations for volunteering were also similar to those of previous generations who donned a uniform in 1914. Some, like Tomkins, considered it a patriotic duty.

Earning peanuts as a farm labourer, Sidney Gordon of the George Gordon First Nation in Saskatchewan signed up in April 1941. “I figured a dollar and a half a day would be better than what I’m doing…I get my food, I get my clothes,” he is quoted in A Commemorative History of Aboriginal People in the Canadian Military.

Some enlisted because their fathers had served in the First World War. Saskatchewan Métis brothers John and James Ballendine were both snipers in the First World War. Eight of their sons served in the Second World War: Benjamin, Edward, Frank, John, Paul, Thomas, Walter and Wilfred. Five served overseas and they all survived the war, although Benjamin was affected by what is now termed post-traumatic stress injury.

Some re-enlisted. Former First World War sapper John McLeod of the Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation (formerly Cape Croker), an Ojibwa band on Ontario’s Bruce Peninsula, joined again and was assigned to the Veterans Guard of Canada. Six sons and a daughter followed him into service; two sons were killed, two wounded. In 1972, McLeod’s wife Marie Louise was the first Indigenous woman named National Memorial (Silver) Cross Mother.

Chief Joe Dreaver of the Mistawasis Cree band in Saskatchewan, who earned the Military Medal in the First World War, brought 17 men with him when he re-enlisted for the Second World War. First World War pilot Oliver Martin, a Mohawk of the Six Nations of the Grand River in Ontario, was active in the Canadian Militia between the wars, entered the Second World War as a colonel, was promoted to brigadier and commanded infantry brigades on the West Coast until he retired in 1944. After the war, he became a magistrate and advocate for Indigenous rights.

Patriotism and heartfelt sympathy for the staff at a residential school in Chilliwack, B.C., who had lost loved ones in the Blitz were the incentive for Russell Modest of the Cowichan First Nation, according to Aboriginal People in the Canadian Military. His residential school experience helped him adapt to military life.

“I just blended right in with it,” he said. He served in the Italian Campaign with the Lanark and Renfrew Scottish Regiment.

In a publicity photo, Private Mary Greyeyes of the Muskeg Lake Cree Nation in Saskatchewan receives a “blessing” from Harry Ball of the Piapot First Nation before beginning her duties with the Canadian Women’s Army Corps. [ av.canadiana.ca]

Indigenous people served in every military theatre and in all services, although the air force and navy had colour bars until 1942 and 1943, respectively. A 1943 report found only 29 Indigenous personnel serving in the air force and nine in the navy, although many non-status First Nations, Métis or Inuit were likely not counted.

Sergeant Samuel Jeffries of Missanabie, Ont., was killed in action while the Royal Air Force’s 104 Squadron was targeting Rommel’s supply lines on Dec. 28, 1942.

“A good number of Mohawks from the Bay of Quinte area, probably due to their familiarity with military aircraft [from nearby RCAF Station Trenton], joined the RCAF,” wrote Fred Gaffen in Forgotten Soldiers.

Sergeant Charles Clinton Topping died on a bombing mission in 1941 with 226 Squadron, RAF; Albert R. Corston of Chapleau, Ont., was of Scottish and Cree ancestry. He took flight training in Canada, was posted overseas in 1942, and served with 67 Squadron, RAF, in Asia. His Hurricane was hit by a Japanese Zero during the attack on Calcutta, India, on Dec. 5, 1943, but he made it back to safety.

Chief Petty Officer George Edward Jamieson was the son of a Cayuga mother and Mohawk father from the Six Nations community of Ohsweken, Ont. He was a sea cadet in Toronto before the war and had been taken on by the navy volunteer reserve as a boy bugler. He transferred to gunnery, was called up in August 1939, and spent the war serving in escorts on convoy duty. His career continued after the war, and he served in Korea aboard HMCS Iroquois.

The Shead brothers—Nelson, Bill and Harry—of Selkirk, Man., with roots in the Fisher River Cree Nation near Lake Winnipeg, joined the navy, capitalizing on their experience on fishing boats. Bill rose to the rank of chief petty officer.

Most Indigenous personnel were treated as equals once they put on their uniforms—but not all.

Marguerite Marie St. Germain, a Métis from Alberta’s Peace River valley, who joined the RCAF Women’s Division in 1942, initially saw Métis people insulted, but that “prejudice diminished as the war progressed and the Métis proved they could perform as well as anyone else,” wrote Gaffen.

Mary Greyeyes, the first Indigenous woman to volunteer for the Canadian Women’s Army Corps, had to stay in a boarding house because she was unwelcome in women’s barracks. But the experience of Margaret Pictou of the Eel River Bar First Nation in Darlington, N.B., was diametrically opposite, Gaffen reported. She did not experience any discrimination during her service in a photographic unit.

Some rued the day they would return to live in a prejudicial society. “Here the boys call me ‘The Saint’ but back in Canada, I’ll be treated just like another poor goddam Indian,” said Sergeant J.F. St. Germain, a Métis, after the Battle of Ortona. “I hope I get killed before it is all over.” A year later, he was, reports Gaffen.

Along with all disembarking soldiers arriving in Canada, Modest was given a liquor ticket; then he was jailed for possession of the ticket.

“The magistrate told me ‘once you entered Canadian territorial waters you were now just another Indian! You have no special privileges and you have to abide by the law.’ You remember these things,” Modest said in an article in the Canadian Military Journal.

“Aboriginal soldiers, free from the constraints of the Indian Act and the watchful eyes of Indian agents, discovered English pubs and lived the life of any other soldier overseas,” notes Aboriginal People in the Canadian Military.

“The Indian and Métis soldiers served just as well as the others,” wrote Colonel J.R. Stone in a letter to Gaffen. “There were just as many drunks and deadbeats among them and just as many disciplined soldiers.”

“Discrimination? Everybody was so involved in what was happening…that nobody was involved in such pettiness,” said Dorothy Asquith, a Métis in the Canadian Women’s Auxillary Air Force, quoted in Aboriginal People in the Canadian Military. “I don’t think you bothered to look at the colour of your buddies’ skin.”

The equal treatment and social acceptance experienced by many Indigenous military members underscored the inequities at home, and coupled with newfound confidence and skills, prodded many veterans into postwar activism.

Many returned from the Second World War “feeling that they received great respect within their family, their community and the country,” said a 2005 article by John MacFarlane and John Moses in the Canadian Military Journal. As well, after the war they were able to capitalize on the education and training they’d had in the military.

Participation in the Second World War did not change conditions for Indigenous people in Canada immediately after the war ended. For example, Status Indians had to wait until 1960 to acquire the federal vote without relinquishing their treaty status.

While the new generation was off fighting on the battlefields of Europe and Asia, First World War veterans continued their fight for rights in Canada.

A Vancouver Sun article about the First Nations delegation to Ottawa in 1943 focused on Francis Pegahmagabow, First World War hero and chief of the Wasauksing (formerly Parry Island) First Nation in Ontario. A sniper credited with killing 378 enemy, he received the Military Medal with two bars.

“The story closed with a stunning revelation,” wrote R. Scott Sheffield in The Red Man’s on the Warpath: The Image of the ‘Indian’ and the Second World War. At a Legion branch, he bought the year’s first poppy with his last 50 cents. “That such an obviously capable man with strong claims on the society’s generosity, as both a war hero and a legal ward of the state, could be brought so low revealed something profoundly wrong with the country.”

When Indigenous veterans returned from the Second World War, reports of their successes overseas and of conditions they faced at home opened the eyes of Canadians to Indigenous issues, and increased support throughout society. But social change is reckoned in years and decades.

Status Indians did not have access to the same services and benefits as other veterans, said the parliamentary committee report Indigenous Veterans: From Memories of Injustice to Lasting Recognition. They were ping-ponged between the Veterans Affairs and Indian Affairs departments.

Their affairs were handled by Indian agents whose goal was assimilation. Status Indians were told they would have to renounce their status to apply for veterans’ benefits. Some found that Indian agents had removed their names from band lists while they were overseas. During the war, their allowances for dependents were funneled through agents, and “there was no way to determine whether the money actually reached the families,” said the report.

Status Indians were not eligible for $6,000 Veterans’ Land Act loans if they lived on reserve lands. And although they were eligible for a grant of up to $2,320, not every Indian agent passed along this news. Only about 1,800 took advantage of the grants. Those who set up farms found limited business opportunities, as they could not sell their produce or livestock without permission of an Indian agent and they could not qualify for bank loans because they did not own the land. They were not able to develop their farms as non-status veterans had, and consequently had less to pass on to their children. In the late 1990s, the federal government compensated veterans, surviving spouses and dependents.

Military service “was a powerful egalitarian experience,” historian Scott Sheffield testified before the parliamentary committee, “and for many of them, sadly, the first and maybe the last time in their lives they felt respected and honoured for their character and capacity.”

As many as 12,000 Indigenous people served in 20th-century wars.

“We were proud of the word ‘volunteer,’” said Second World War veteran Syd Moore of Moose Cree First Nation in Ontario in a CBC Remembrance Day interview in 1990. “Nobody forced us. We were good Canadians—patriots—we fought for our country.”

[LAC/PA-129070]

Charles Henry Byce, whose mother Louisa was from Moose Cree First Nation in Ontario, had big shoes to fill when he enlisted in the Lake Superior Scottish Regiment in 1940. His father Henry, of British descent, had earned the Distinguished Conduct Medal and the French Médaille Militaire in the First World War.

Charlie Byce repeated the feat in the Second World War, the only one in his regiment and one of only a handful of Canadians to earn a DCM and a Military Medal.

Byce, an acting corporal, was among two dozen members of his regiment who crossed the Meuse River in the Netherlands on Jan. 21, 1945, intending to sneak behind German lines to bring back prisoners for interrogation.

Byce’s five-man patrol provided cover for the reconnaissance group, which came under fire from three enemy positions immediately after stepping ashore. Byce himself used grenades to take out two entrenchments. When his patrol came under fire again, Byce charged the German dugout and lobbed in a grenade, clearing the way for his comrades to make it back to their own lines.

On March 2, Byce, now an acting sergeant, was in a company that occupied some buildings near the Hochwald Forest. Soon the enemy was peppering them with shells. The company commander and every officer were casualties.

Byce assumed command as the Germans began their counterattack. Moving from gun to gun, Byce led a fierce assault that claimed 20 enemy casualties and drove the attacking infantry back. As four enemy tanks moved in, Byce fired a PIAT (Projector, Infantry, Anti-Tank), knocking out the lead tank with his third shot. With no anti-tank ammunition left, he directed his men to hold fire until the remaining tanks had passed, then attack the accompanying infantry. After some fierce fighting, the Germans demanded he surrender; instead he led his men, under fire, to safety.

“His gallant stand, without adequate weapons and with a bare handful of men against hopeless odds, will remain, for all time, an outstanding example to all ranks of the regiment,” concludes the citation to his Distinguished Conduct Medal.

In the Second World War, about 160 Canadians earned the DCM, and only a handful also earned the Military Medal.

After the war, Byce worked at a paper mill near Espanola, Ont., and died in 1994, in Newmarket, Ont. A bronze monument commemorating Byce was unveiled in 2016 on the grounds of the Harry Searle Branch of The Royal Canadian Legion in Chapleau, Ont., where he was born while his father was off fighting in the First World War. His medals, along with those of his father, are in the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa.

[SCAA/ MLCN-214-0003]

When he enlisted in the army in 1940, 24-year-old David Greyeyes-Steele, a grain farmer and athlete from Muskeg Lake Cree Nation in Saskatchewan, could never have imagined where that action would lead.

Overseas, he was steadily promoted and was the first Status Indian commissioned as an officer overseas, according to the World Wars Aboriginal Veterans website. He also played on the soccer team that won the Overseas Army Championship in 1942.

During the Battle of Rimini in Italy, Greyeyes-Steele was commander of a Saskatoon Light Infantry (Machine Gun) mortar platoon which, along with a Greek Mountain Brigade, secured one flank of the 1st Canadian Infantry Division across the Marano River on the hard slog to Rimini, at the cost of more than 100 casualties. Greyeyes-Steele was one of 15 Canadians to earn the Greek Military Cross for their performance during the battle.

He served in Sicily, Italy, North Africa, France, Belgium and the Netherlands, was an intelligence officer in Germany, and would have served in the Pacific if Japan had not surrendered.

After the war, he returned to farming and married veteran Flora Jeanne, one of the first Indigenous women to serve in the RCAF Women’s Division. An ardent soccer player, he was inducted into the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame in 1977.

Greyeyes-Steele became chief of the Muskeg Lake Cree Nation in 1958, and in 1960 began a public service career, becoming the first Indigenous regional director of the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada.

In 1977, he was appointed a Member of the Order of Canada and received the Saskatchewan Order of Merit in 1993. He died in Saskatoon in 1996.

[LAC/PA-142289]

Near Littoria, Italy, in February 1944, Reconnaissance Sergeant Tommy Prince, a member of the Devil’s Brigade, ran 1,400 metres of telephone wire from Allied lines to an abandoned farmhouse, where he set up an observation post just 200 metres from enemy artillery, and began his reports.

When shelling cut the line, Prince got into civilian clothing, grabbed a hoe and under guise of weeding crops, repaired the wire right under noses of observing enemy, earning a Military Medal.

Prince was admired for his cunning, courage and covert moves. “The Germans thought he was a ghost or a devil,” a comrade recalled in P. Whitney Lackenbauer’s profile, “A Hell of a Warrior” in the Journal of Historical Biography.

“They could never figure out how he passed the lines and the sentries. He would steal something, like a pair of shoes, right off their feet.”

In September 1944, Prince and a private located an enemy reinforcement camp, hiking 70 kilometres across the mountains to report. Prince then led his battalion back to the enemy camps.

Prince (above, right, with his brother Morris) was recommended for the Silver Star, an American army decoration for gallantry in action.

King George VI placed the Military Medal on Prince’s chest, as well as the Silver Star with ribbon on behalf of the president of the United States. Only 59 Canadians earned the Silver Star during the war, and only three of them also earned the Military Medal, wrote Janice Summerby in Native Soldiers, Foreign Battlefields.

Prince, of the Brokenhead Ojibwa Nation in Manitoba, was a descendant of Peguis, the Saulteaux chief who led his people from Ontario to the Red River area in 1790, eventually settling near what is now Selkirk, Man.

He is also a descendant of Chief William Prince of the Peguis First Nation, who headed the Nile Voyageurs, boatmen hired in 1884 to carry a military party up the Nile River in an abortive attempt to rescue British General Charles George Gordon, beleaguered in Khartoum, in what is now Sudan.

Prince joined the army cadets as a youth. “As soon as I put on my uniform I felt like a better man,” he said in a 1952 article in Maclean’s. He began his military career in 1940 as a sapper with the Royal Canadian Engineers, assigned to home guard duty in England. “I joined the army to fight, not to sit around drinking tea,” he told a comrade.

In 1942, Prince became a member of the 1st Special Service Force, a joint Canadian-American unit best known as the Devil’s Brigade.

Back home after the war, he was elected chairman of the Manitoba Indian Association and lobbied for changes to the Indian Act. He believed veterans were in the best position to fight for a better future for Indigenous people.

“My job is to unite the Indians of Canada so we can be as strong as possible when we go to the House of Commons.” Once there, he described returning home after discharge, “but there is no way to make a living.” He wanted better financial support, hospitals, improved sanitation, schools.

He was ultimately disappointed. The resulting changes to the Indian Act lifted the restriction on off-reserve travel and the bans on political organization and traditional spirituality. But they did not go far enough to ensure the permanent improvements to reserve and economic life that he had envisioned.

In August 1950, Prince enlisted to fight in Korea. “I owed something to my friends who died,” he said. He joined the 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, which was awarded the U.S. Presidential Unit Citation for warding off wave after wave of attacks on Hill 677 during the Battle of Kapyong in 1951.

“All my life, I wanted to help my people recover their good name,” Prince said in the Maclean’s article. “I wanted to show they were as good as any white man.”

After recovering from a knee problem, Prince signed up for a second tour, joining the 3rd Battalion, PPCLI, in Korea in March 1952. He was among nine wounded at the Second Battle of the Hook on the Samichon River in November 1952, but soldiered on. And on, until he suffered what was then called battle exhaustion, likely post-traumatic stress disorder, for which he was hospitalized. The armistice was signed during his recovery.

After the war, Prince slowly descended into alcoholism and homelessness, pawning or selling his medals to make ends meet. They now reside at the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature.

More than 500 people, including consuls from France, Italy and the United States, attended his funeral in 1977. “He was a hell of a warrior,” said Don Genaille, an army comrade.

[Combat Camera/ISO2012-1012-06; Wikimedia]

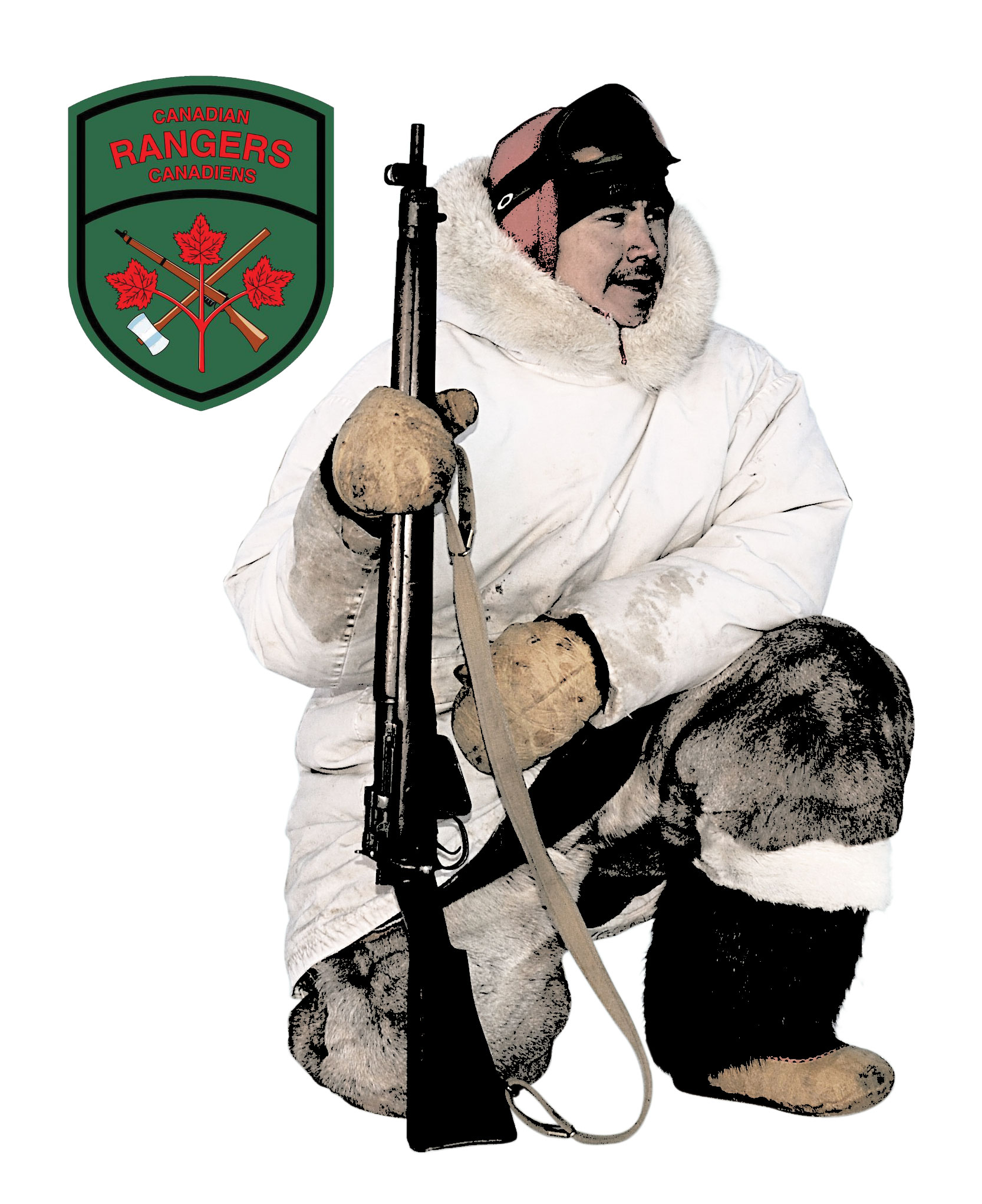

At the dawn of the Cold War, it was a challenge to maintain sovereignty and have a military presence in Canada’s vast north, with its remote and isolated communities, its extremes of climate and geology. How was a country with such a small population going to stand on guard?

The Canadian Rangers, established in 1947, was the solution. The reserve force was patterned after the Pacific Coast Militia Rangers who patrolled in British Columbia during the Second World War.

“The Rangers represent a flexible, inexpensive and culturally inclusive means of ‘showing the flag’ and asserting Canadian sovereignty in remote regions,” said a 2007 article by P.W. Lackenbauer in the Canadian Army Journal.

Today, there are about 5,000 rangers in about 170 patrols across the country, mostly in the Far North. More than 60 per cent are Indigenous, speaking more than two dozen languages and dialects.

These part-time reservists watch for unusual activities along the coast, in the hinterland and in their communities. They also work in search-and-rescue operations and use their geographic and traditional know-ledge to help Canadian Armed Forces members working in the North.

Rangers responded after an avalanche ripped through a New Year’s party of 400 people in the Inuit community of Kangiqsualujjuaq, Que., in 1999. Nine people died. In -20°C temperatures and 100 kilometre per hour wind, 28 local Rangers freed trapped people, joined by about 40 Rangers from 11 other patrols.

General Maurice Baril, then chief of the defence staff, awarded the CAF Unit Commendation to the 2nd Canadian Ranger Patrol Group.

Rangers are based in remote com-munities across the North. In the Arctic, the vast majority are Inuit and many speak solely Inuktitut.

Many serve a long time, as there is no mandatory retirement age. Ollie Ittinuar was still serving at the age of 88 when he was inducted into the Order of Military Merit in 2009. He had joined in 1984, at 60. Johnny Tookalook and Johnassie Iqaluk from Sanikiluaq, Nunavut, enlisted in 1947 and served for more than five decades. Abraham Metatawabin, a Mushkegowuk Cree from Fort Albany, Ont. was honoured for 22 years of service in 2015, when he was 92. At the time, he was the oldest serving member in the Canadian military.

Fontaine Fiddler, of the Oji-Cree First Nation 600 kilometres northwest of Thunder Bay, Ont., earned a Medal of Bravery in 2016. He and a cousin noticed a house was on fire, and the family, two adults and four children, were trapped inside. Fiddler, of the 3rd Canadian Ranger Patrol Group, found a way in and brought the children out to safety before returning to the burning house for the adults.

“I’m very proud to be a Canadian Ranger,” said Sergeant Nick Mantla of Wha Ti First Nation in the Northwest Territories, quoted in Aboriginal People in the Canadian Military. “It’s a way to serve my country as well as my people.”

Advertisement