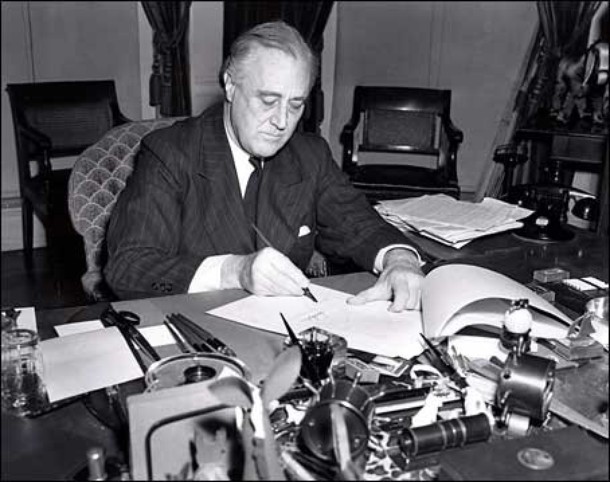

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs the Lend-Lease policy to give aid to Britain, Free France, China and other Allied nations in March 1941. [Wikimedia]

Months before it entered the Second World War in December 1941, the United States invested heavily in the Allied cause by instituting the US$50.1-billion Lend-Lease policy, providing food and war materiel to Britain and other friendly nations.

Worth nearly US$600 billion in today’s currency, the measures under what was formally known as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States lasted the rest of the war and helped turn the tide of battle both in Europe and the Pacific.

But for all the warships, tanks, jeeps and other arms and equipment it provided, it was a little-known aviation fuel—top-secret at the time—that played a critical role in delivering the war’s first victory over Hitler and his forces’ relentless advance.

There is no disputing the commitment and courage of Churchill’s “Few,” the 3,000 or so British, Commonwealth and other pilots who flew fighters over Britain and the English Channel in the summer and fall of 1940. But without the “miracle” of the high-octane fuel that powered their Hurricanes and Spitfires, purchased on a cash-and-carry basis, the battle, and the war, may well have been lost.

Squadron Leader Douglas Bader (fourth from right) with Canadian pilots of his 242 (Canadian) Squadron, RAF, alongside a Hurricane at Duxford, England. [Devon/Air Ministry/Second World War Official Collection]

The newly developed aviation gasoline, or avgas, was a 100-octane fuel that could outperform the Germans’ 87-octane and overcome any superiority the Luftwaffe fighters and their seasoned pilots might have had in the war’s early stages.

The new fuel was called BAM 100 (British Air Ministry 100 octane), or 100/130 octane. The 130 referred to the fact it gave British aircraft up to 30 per cent more horsepower on take-off and climb than could any ordinary octane.

This increased the planes’ top speed by 25 to 34 miles per hour up to 10,000 feet.

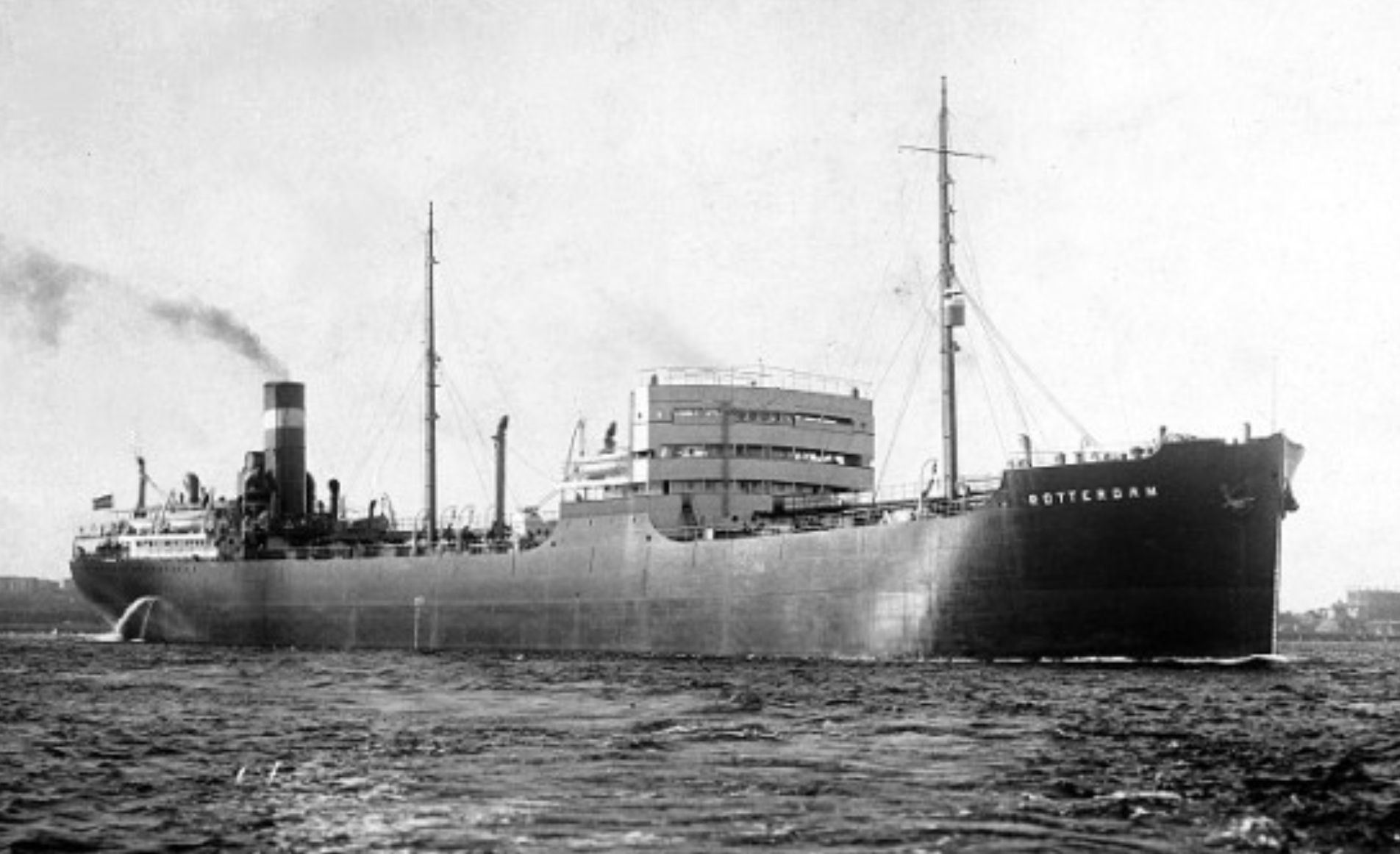

The first tanker load of BAM 100 was shipped in limited quantities to England for stockpiling in June 1939. The Second World War began that September with Nazi Germany’s invasion of Poland.Shipments were stepped up and by March 1940, the New York Times reported in a 1978 feature, the RAF was “converting the Merlin engines of every Spitfire and Hurricane fighter from 87‐octane gasoline to BAM 100.”

The Battle of Britain formally began on July 10, 1940, although German raids had been taking place for weeks.

With coastal radar stations giving the defenders just a few minutes’ warning of impending attacks, the juiced-up fuel enabled British aircraft to climb faster and higher and thus gain the critical high ground over approaching Luftwaffe formations.

“It is an established fact that a difference of only 13 points in octane number made possible the defeat of the Luftwaffe by the RAF in the fall of 1940,” wrote Vladimir Anatole Kalichevsky in his 1943 book The Amazing Petroleum Industry. “This difference, slight as it seems, is sufficient to give a plane the vital ‘edge’ in altitude, rate of climb and maneuverability that spells the difference between defeat and victory.”

The boost startled the Germans, wrote Tim Palucka in the journal Invention and Technology in 2005. Many had fought the Spanish Civil War and the Blitzkrieg across continental Europe which culminated in the fall of France and evacuation of Allied forces at Dunkirk in May-June 1940.

“Luftwaffe pilots couldn’t believe they were facing the same planes they had fought successfully over France a few months before,” wrote Palucka. “The planes were the same, but the fuel wasn’t.”

The Germans, say historians, did not discover the secret of Britain’s aviation fuel until shortly before the battle ended, when a Spitfire on bomber escort went down in occupied Belgium.

“German technicians swarmed over the wreck,” The Times reported. “They were startled to find, on testing the fuel left in the tanks, that the British were not using 87‐octane gasoline.

“They were further chagrined to discover that their best fighter, the Messerschmitt 109E, could not use the superior British fuel because its engine was not sufficiently supercharged.”

In today’s age of reactive isolationism and anti-global pushback, the story of BAM 100 represents a lesson in international co-operation and teamwork, how a revolutionary aviation fuel was developed by American companies, using a process invented by a Frenchman, and shipped to a British air force in convoys comprising ships of every description and nationality—a motley collection of mongrel tankers, many of them “refugees” from countries then occupied by Adolf Hitler’s troops.

Palucka’s 2004 article was entitled “The Wizard of Octane.” The “wizard” was Eugene Houdry, a Frenchman who settled in America and worked for the Sun Oil Company where, according to Palucka, “his miraculous catalyst turned nearly worthless sludge into precious high-octane gasoline and helped the Allies to win World War II.”

In his article, Palucka links the provenance of the high-grade fuel to a single event.

Eugene Houdry holds a small catalytic converter in 1953. [sciencehistory.org]

Normally, the audience thinned out by the time the technical papers were presented at the end of the meeting. Not this day. Pew explained to a full house how the company plant in Marcus Hook, Pa., was processing thick oils into high-grade gasoline.

Left over from previous distillations, the best anyone could previously do with these “heavy bottoms” was convert them into fuel oil, at little profit. By turning them into gasoline, Sun Oil had increased its gasoline yield from crude from the previous standard of 25 per cent to as high as 50 per cent.

Refuelling and rearming No.601 Squadron Hawker Hurricanes at RAF Tangmere, 1940. [RAF Museum]

The New York Times story, written five years earlier than Palucka’s journaled article, doesn’t mention Houdry, Pew or Sun Oil. Its focus was on scientists at the Standard Oil Company of Linden, N.J., (now Exxon) who had also been working in high-octane fuel development.

Their main contribution, it appears, was in the process, adapting existing 100-octane gas for use in the British Merlin engine and, critically, enabling production increases to the point that all Hurricane and Spitfire squadrons, rather than a handful, could convert to the new booster juice in the first half of 1940.

The American contributions to fuel production were irreplaceable, Palucka asserted, because as war clouds formed over Europe during the 1930s, American companies were extracting about 60 per cent of the world’s petroleum, with the Soviet Union accounting for 17 per cent and Britain and the Netherlands most of the rest.

“The Axis powers extracted virtually no petroleum,” he reported. “The Germans had made great strides in producing liquid fuels from coal, and after their early territorial conquests, notably in Romania, they had ample oil supplies.

“But with almost no homegrown knowledge base in oil refining, they were not able to catch up with the latest American advances…. Not until after the war did Germany or Japan begin producing 100-octane gasoline.”

Pick up our special edition of Canada’s Ultimate Story, Canadians in the Battle of Britain, a gripping account of the critical fight for air supremacy, on newsstands now!

Advertisement