The Allies called it Enigma (Greek for riddle). Each branch of the German services developed its own version, but at the heart of them all was a set of five to eight interchangeable rotors that continuously scrambled the letters of the alphabet. There were 103 sextillion possible settings—that’s 103 with 21 zeroes behind it.

Starting positions of the rotors were changed with each message and the machines were reset every day, according to a key list distributed monthly.

The Germans thought the codes were unbreakable. They were wrong.

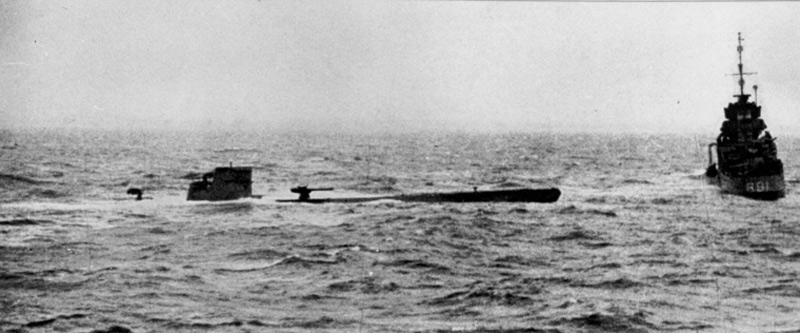

But to break the code, the Allies needed an Enigma machine. In May 1941, they got one. The Royal Navy captured a U-boat in the North Atlantic, recovering its Enigma machine, cypher keys and code books. Normally, U-boats in danger of capture were scuttled in order to keep the machines out of Allied hands. But, expecting to be rammed and sunk, the captain of U-110 ordered his crew to abandon ship.

The U-boat was not rammed but boarded. U-110 was then sunk by British ships and the fact it had been boarded became a highly guarded secret.The machine was sent to Bletchley Park, where cracking the Enigma code became the focus of computer pioneer Alan Turing and his team of cryptographers, who succeeded July 9, 1941.

84,000 German army, navy and air force messages were being cracked each month.

From that date forward, except for one short period, the Allies were able to decode German naval signals, allowing them to better defend against the threat of U-boat wolf packs.

It has been estimated that the efforts of Turing and his fellow code breakers shortened the war by several years and saved millions of lives. Without their contribution, German defences along the French coast would have been stronger, prolonging the war.

By 1943, a total of 84,000 German army, navy and air force messages were being cracked each month, greatly contributing to D-Day planning. This intelligence was known as Ultra.

“It was thanks to Ultra that we won the war,” said British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

Advertisement