A convoy of merchant ships assembles in Bedford Basin in 1942. In the upper left corner, the Narrows opens into Halifax Harbour and the North Atlantic beyond.

[Nova Scotia Archives]

Accessed by rail, its proximity to both North American manufacturing hubs and the fighting overseas, facilitated by a large, deep, protected, ice-free harbour, made the capital of Nova Scotia the ideal staging point for transatlantic convoys ferrying troops, equipment, munitions, food and other supplies critical to the Allied war effort.

The city was well-practised for its role in history’s greatest conflicts. It had been a naval base since its founding in 1749, a key staging point for the Royal Navy and privateers alike through the American Revolution and the War of 1812, the world’s gateway to domestic and U.S. markets and, for Canadian commerce, a jumping-off point to ports around the planet. A British admiral of the day called Halifax “the most important port in the world.”

The great wars of the 20th century, however, infused new life into what had long been—despite its importance—a dull, grey town, the city that had been devastated in 1917 by what today remains history’s largest non-nuclear artificial explosion.

In 1939, the combined population of Halifax and Dartmouth, the community on the eastern shore of the city’s harbour, was 77,836. More than 87 per cent lived in the former. At its wartime peak in 1944, the twin cities’ population had topped 124,000. Dartmouth’s had almost doubled.

It was a boom town, of a sort—more connected to and involved in both world wars than any other Canadian city. The enemy was just offshore; ships were sunk just beyond the harbour mouth.

By the 1940s, a new Canadian navy had taken root in Halifax. Allied warships came and went. The harbour was crowded with vessels of every size and shape. The streets bustled with uniformed men and women—some stationed there, others just passing through.

Coming and going over repeated crossings—loaded to the gunnels outbound, deadheading ballast coming back—merchant seamen from the world over converged on the city that would ultimately become the jewel of Atlantic Canada.

Eateries and sidewalks were a cacophony of languages and dialects—French, foreign to many Haligonians at the time, and all manner of English from varieties of American and British mixed with Dutch, Norwegian, Greek, Russian and more.

The North Atlantic and Murmansk runs were fraught with danger and discomfort, both of the environmental and human varieties. Raging seas, bitter cold and lurking U-boats imposed unique forms of stress on sailors and seafarers, 72,000 of whom died between 1939 and ’45.

Layovers and time in port afforded opportunities to blow off steam. The city, however, was overcrowded and underserviced. There were no bars, per se—but there were liquor stores and speakeasies. Line-ups, sometimes hours-long, formed at restaurants, clubs and movie theatres.

The inevitable drunkenness, carousing and brawls, combined with the inconveniences of wartime shortages compounded by overpopulation, didn’t sit well with many locals. Then the powers that be decided to shut the city down on VE-Day—including the liquor stores. Uniformed celebrants looted and trashed the place. Many locals were more than happy to see the flood of humanity recede.

Depth charges at the ready, a lookout aboard HMS Viscount, a V-class destroyer, watches over a convoy in mid-Atlantic in the fall of 1942.

[Lieut. (N) H.W. Tomlin/RN/IWM/4700-01]

“For, without its magnificent harbour, Halifax could not have become either the meeting-place of so many types of allied nationals and the haven of so many allied seamen.”

But in 1943, there was no time for discontent. The buildup to D-Day had begun and the city was filled with unprecedented activity—important work.

At the Halifax Herald and Mail newspapers, illustrator and editorial cartoonist Bob Chambers was in high flight.

Over the course of 53 years, Chambers, as he was known, would become an institution throughout the Maritimes and, indeed, Canada, his editorial cartoons both gleefully anticipated and anxiously awaited, if not dreaded, depending on one’s station in society and politics.

(Outgoing Conservative premier Gordon Harrington told him after losing the 1933 provincial election: “You know Bob, you libeled me 23 times in 23 cartoons and I didn’t sue you. But I sure thought about breaking your nose.”)

In a military town, in the midst of a conflagration the likes of which the world had never seen, the family-owned newspapers were lifelines for those on the home front, links to the men and women across the pond. They were unabashed boosters of the war effort and Chambers was no exception.

He regularly created illustrations memorializing lost ships and men of the Canadian navy. They would go on to form a series of commemorative cards after the war ended (see the coming feature in the January/February 2025 issue of Legion Magazine).

This booklet with a dozen illustrations by Bob Chambers and copy by Frank Doyle sold for 25 cents in the fall of 1943. It showed what daily life was like in Canada’s primary front-line port in the Battle of the Atlantic during WW II.

[Bob Chambers/Halifax Chronicle & Mail]

Nova Scotia’s longtime provincial archivist, Daniel C. Harvey, wrote in the booklet’s forward that Chambers’ work afforded “convincing evidence that such [wartime] activities could not be carried on in any ordinary town, or in any ordinary seaport.”

“For, without its magnificent harbour, Halifax could not have become either the meeting-place of so many types of allied nationals and the haven of so many allied seamen, with their moving stories of dangers met and overcome, or the embarkation port of such varied types as are here depicted in characteristic mood.”

He alludes to the city’s history and notes how “Halifax has been both a military and naval centre and the capital of a colony or province, striving to meet the needs of its normal civilian life as well.”

“Haligonians have learned to meet emergencies and, in their clubs, hostels and churches to discharge their obligations to the thousands who pass through their gates, hoping they may carry with them pleasant memories of their sojourn in the city and some knowledge of its colourful history.”

Chambers, he said, juxtaposes the old—the fort on Citadel Hill, the town clock, the Old Burying Ground and other historic landmarks—with “the complexity and evolution of modern life,” namely the likes of an ox cart and jeep side-by-side boarding a steam ferry.

Doyle, meanwhile, accompanies Chambers’ sepia- and blue-toned illustrations with vivid descriptions of life in the wartime city.

Here are some of Chambers’ illustrations and excerpts from Doyle’s accompanying prose:

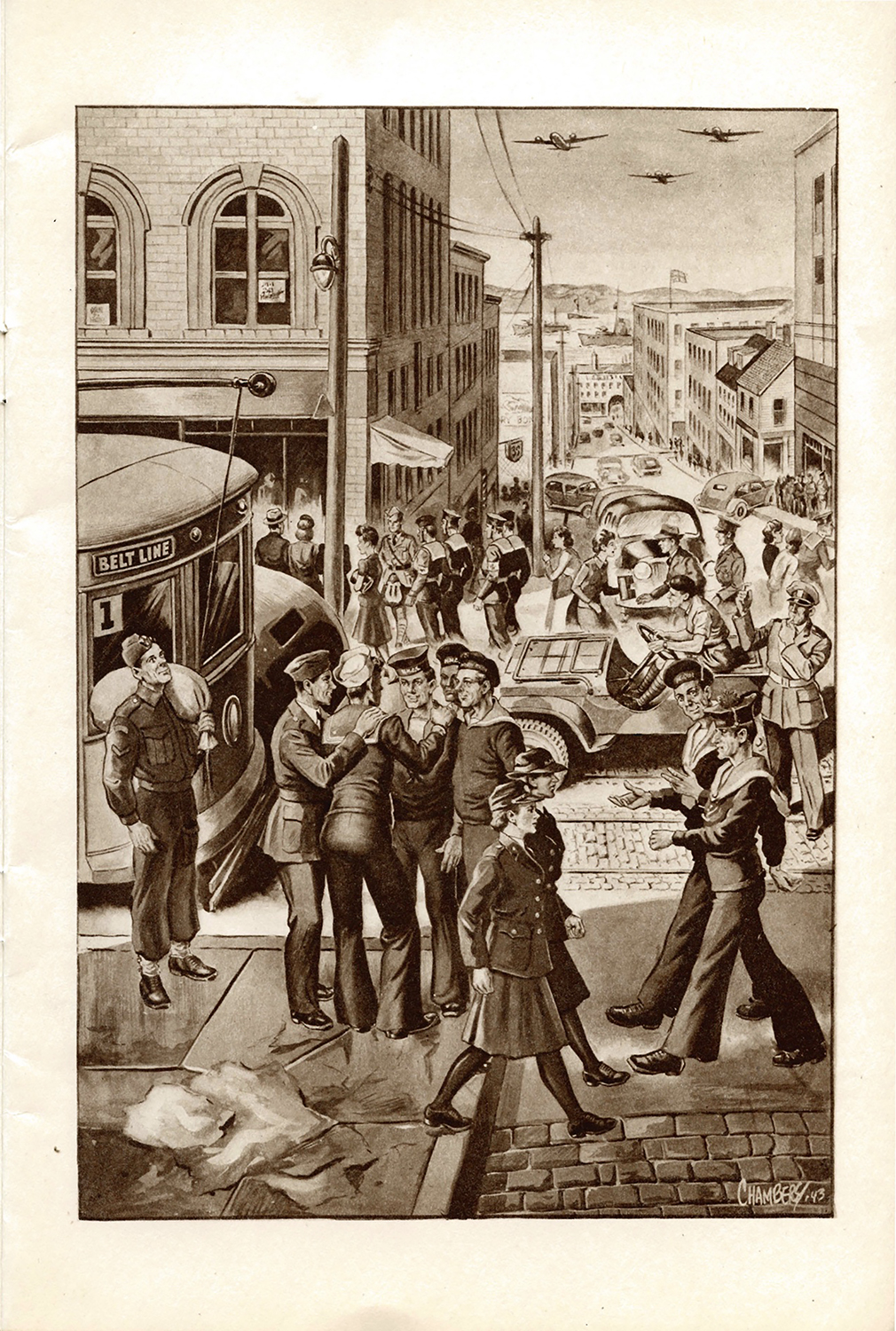

A CROSS-ROADS OF THE WORLD

Chambers depicts the corner of Barrington and Sackville streets in what Doyle describes as “the United Nations where men of many lands and races pass day after day in the course of work or leisure.”

“Before Hitler marched into Poland, this was merely a busy, downtown spot in a middle-sized maritime city,” he writes. “Trams with empty scats rattled by; taxis in abundance rolled along and private cars went dashing out of the city on pleasant holiday and week-end journeys.

“Now the traffic policeman blows his whistle and waves his signals to a dwindling flow of private cars and a crowd of pedestrians as cosmopolitan as might be found in London or New York, for this is a cross-roads between the Old World and the New.

“Warworkers, servicemen and servicewomen, and mere civilians of no particular calling jostle one another on curbs and crowded street cars while busy jeeps wheel past.

“Men of the Allied navies pause to chat—the Yank who had been in the Solomons, the fair-haired stoker whose home was burned at Narvik, the lad from Rotterdam, the boys whose red pompoms and Lorraine crosses show they chose deGaulle instead of Vichy, and the grim-faced Cockney whose family died in the London blitz.

“Smart costumes of khaki and navy and airforce blue proclaim that Halifax women and their sisters from Vancouver and all the places between are in this world struggle at the side of their men. Tough old salts may mutter but they salute lieutenants with lipstick!”

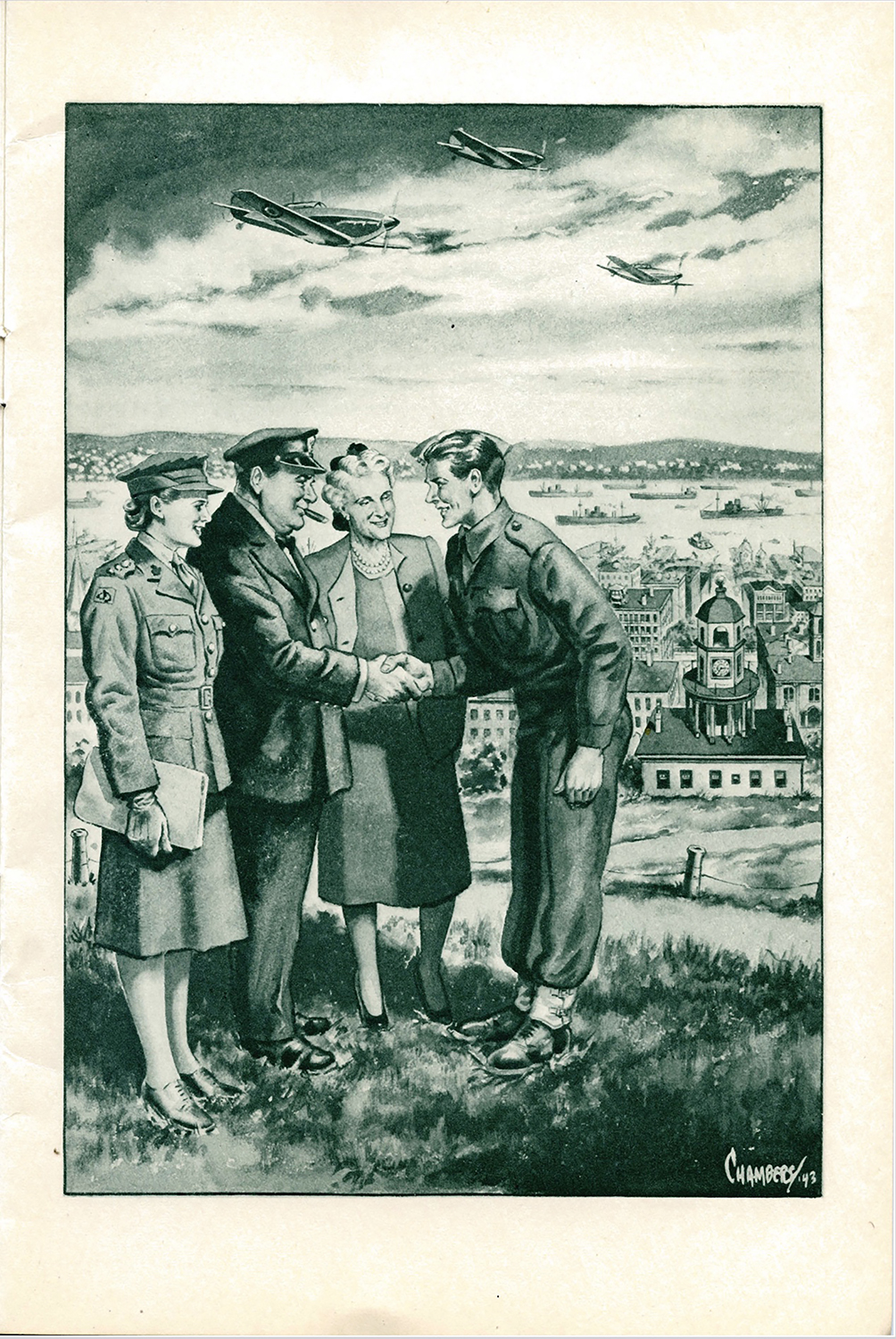

ON THE CITADEL

“In the shadow of Citadel HilI,” Doyle writes, “colonists 194 years ago built the first settlement, sheltering it behind wooden stockades.

“From its heights once pointed the guns which have made this city the ‘Warden of the Honor of the North.’

“Along its base have marched famous regiments, while through the streets sprawling down to the sea have moved prisoners of war and press-gangs, merchants, refugees from rebel colonies, a host of ordinary folk.

“From the Citadel’s heights have flown signals to warn of the enemy’s approach or to tell of the safe arrival of [a] friend from overseas. Semaphores have marked out code words to the outer forts and have relayed messages at royal behest to inland settlements.

“From its slopes have sounded guns to set the city’s time; its weather markers have foretold storm; flags and pennants have made gay with color countless ceremonial occasions.

“Citadel Hill is in war garb now. Men in khaki march its roads, stand guard at its gates…when on its crest stood Winston Churchill, the Empire’s Leader, gazing down on ships of war and trade at anchor in the harbour.”

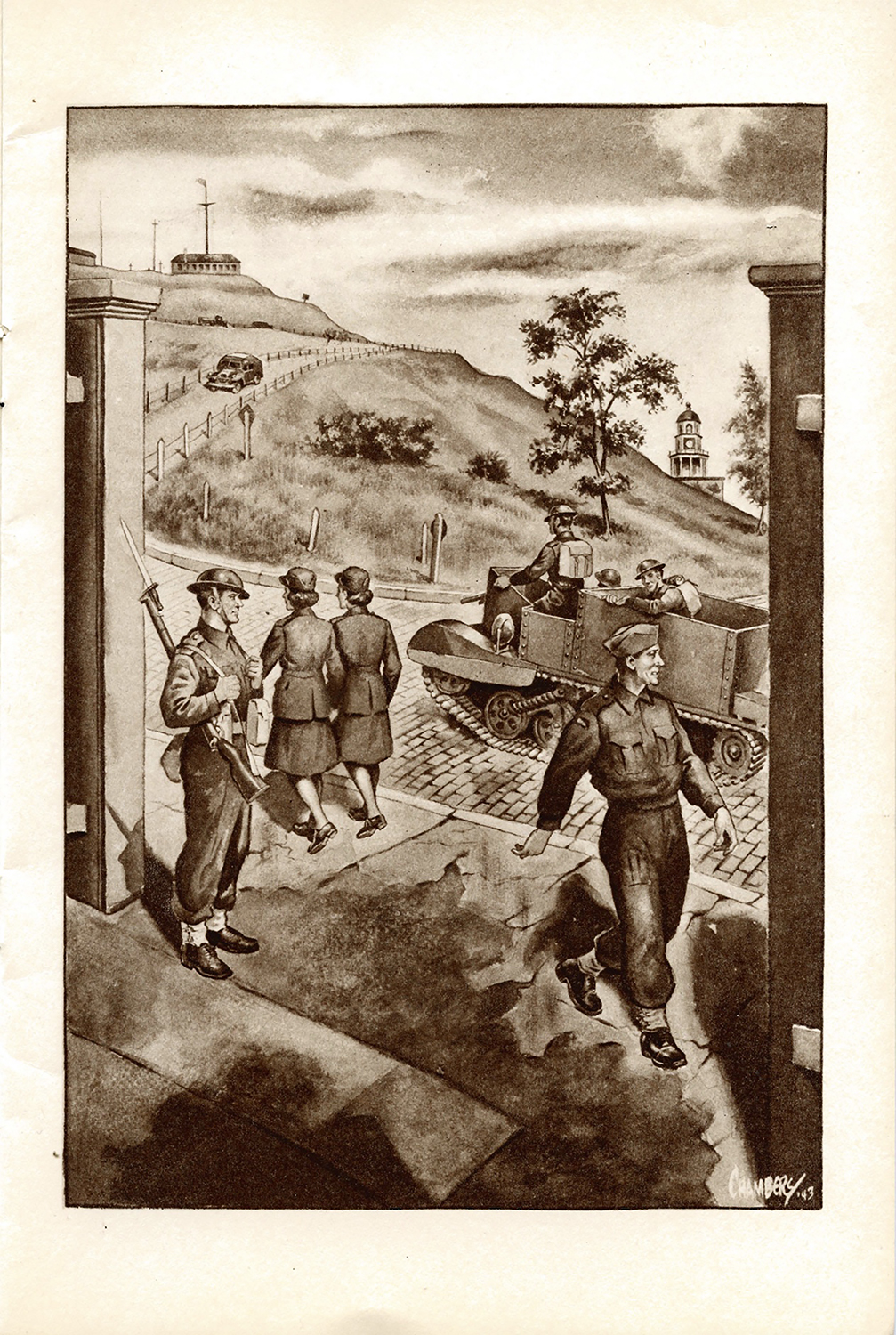

THROUGH THESE PORTALS

“Barrack Square is a term of deep meaning to Halifax. Civilians, as they pass by sentried gates, merely glimpse a paved space. But on such squares, bounded by rambling, red, wooden buildings, many regiments have been mustered….for the first time in Halifax when fresh from other lands…for the last time after their station here had been completed…. Men have met there for the march to Quebec in ancient days…for final orders before embarking on service to end for so many on the soil of France and Flanders.

“Today, as in those other days of war, parade grounds echo to the tread of troops and through those gates on Sackville Street pass soldiers and seamen and airmen of many nations to spend hours ticked off by the Town Clock sitting sedately on Citadel Hill.

“Back of those gates stand galleried barracks; there…are messes where stories of men who wage battles have been told, re-told, and, unwritten, made into legend.

“Past those gates that open on South Barrack Square go thousands each day, men and women of the services, civilians who think themselves harried, schoolboys and girls who will be the soldiery of tomorrow.”

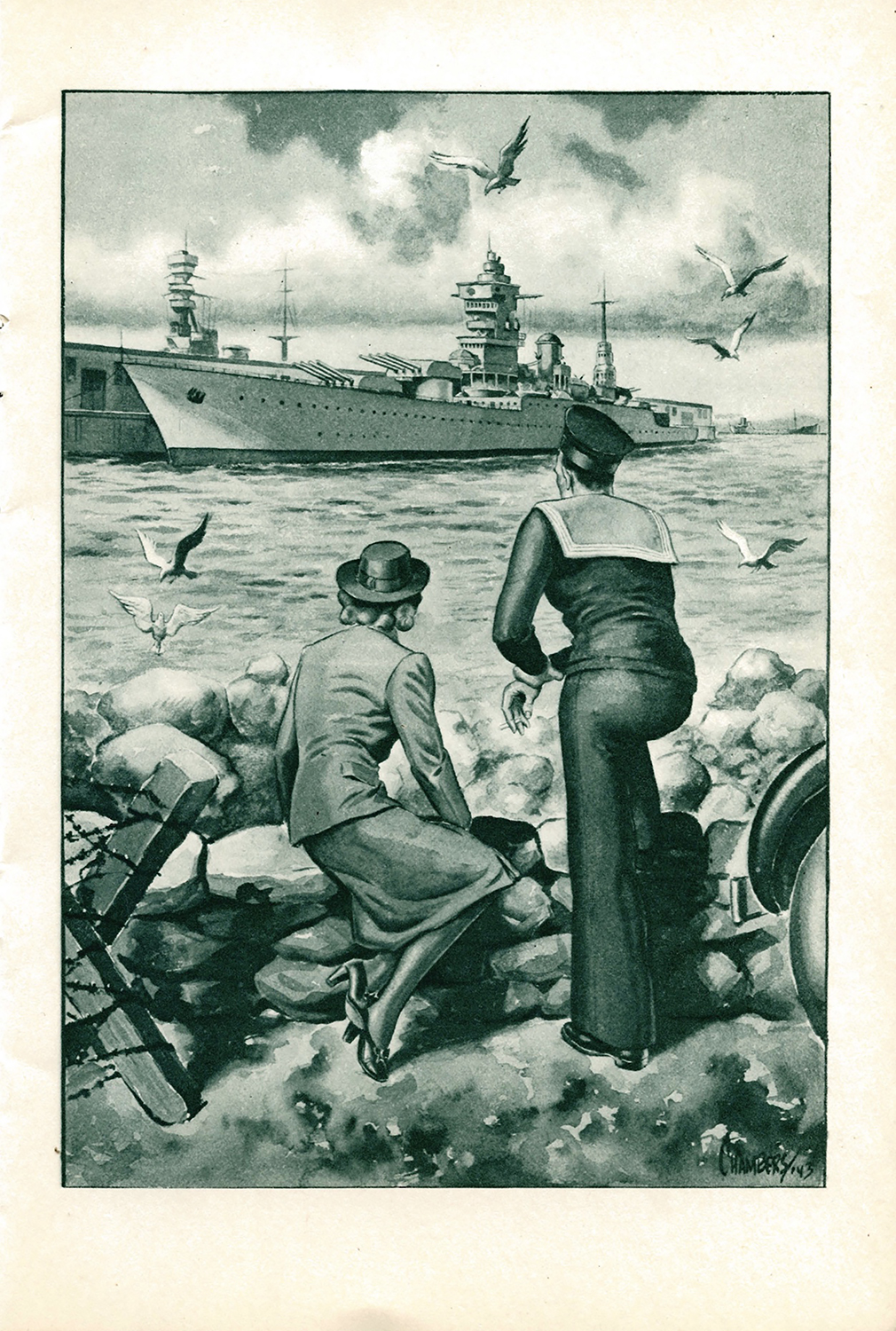

MEN OF WAR

“Halifax has watched from such seawall vantage places many fleets that have made this port since war began. From the East Indies, they have been bound north to Murmansk; having rounded the Cape, they are retracing their course southward again to the Spanish Main. Ships have gone out from here to hunt down great ships and small—the Graf Spee and the Bismarck, and numbered but otherwise anonymous underseas raiders. They have left in flotillas guarding convoys or have slipped away singly under sealed orders.

“Some ships have come back many times; others have not repassed the harbour gates and some never will.

“Royal Navy, Canada’s own fighting ships and those of all the navies of this Commonwealth, of the United States, French, Dutch, Greek, Polish, Russian, Norwegian—war vessels of the United Nations have anchored here….

“Uniformed men have marched ashore in hundreds. They have filled shops and eating houses. When the war was new they found shelter in doorways or slept on counters or under tables on their nights away from ships. They have carried home from Halifax soap and souvenirs, silk stockings and cheese. They have made streets ring with high words and laughter. They have found and made and held friends. They have hunted out historic places, learned a little about Canada and more about Canadians, and have mingled with fellow fighting men in all the services foreign to them….

“They have spent hours on the shoreline measuring their own fighting ships and telling tales of adventure in far-away lands, of battles in the skies and beneath the sea.

“Such tales will be remembered long after this war has gone.”

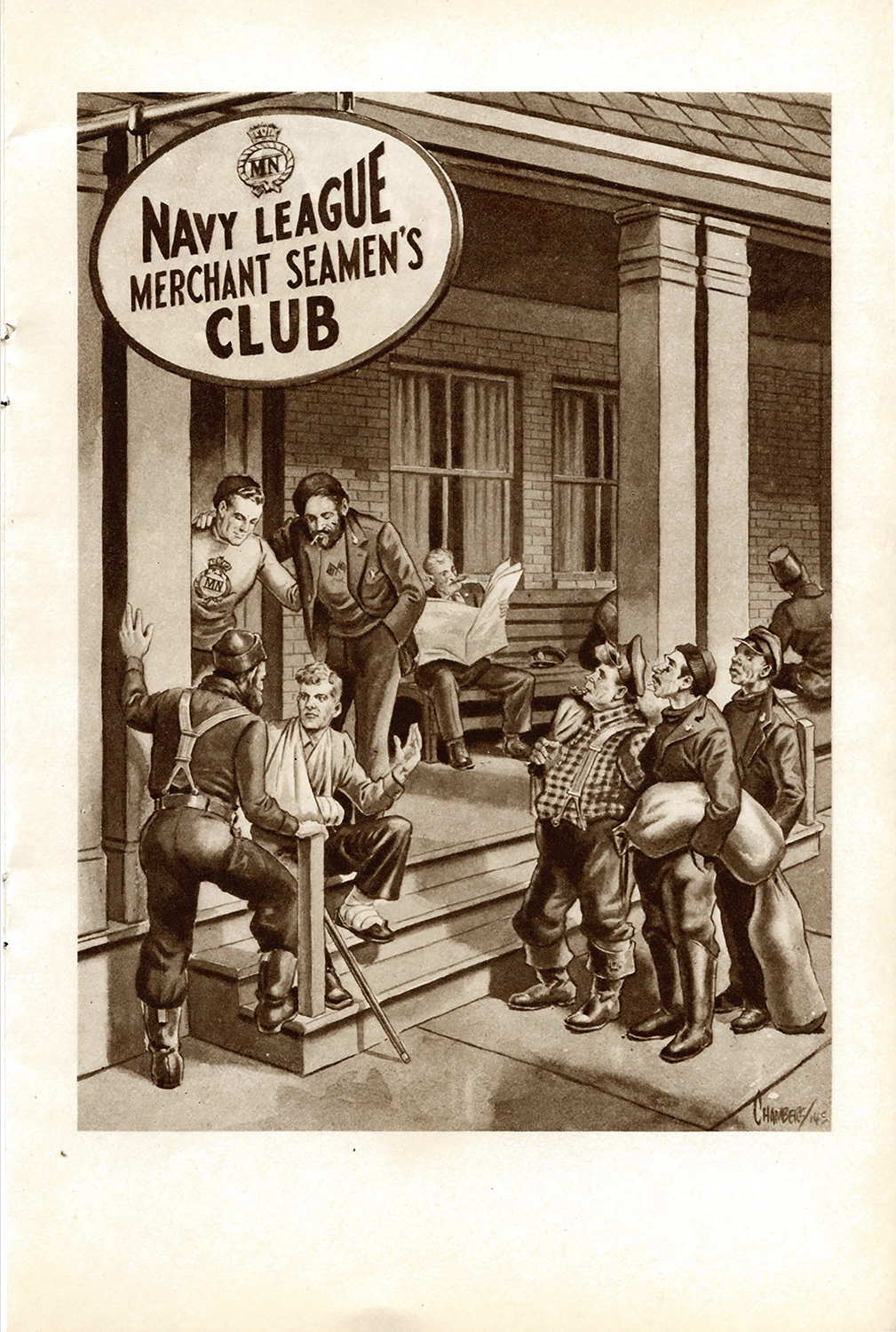

MEN OF THE SEA

“The Free Frenchman could speak no English or Spanish; the Spaniard could talk neither French nor English, but the blond, lackadaisical Englishman was a master of his own tongue and of both others as well, so conversation proceeded easily as the men from three ships, as many countries and countless ports tarried a few hours in Halifax….

“Men of many races—women, too—back from the sea in their ships.

“Men in sweaters and sweatshirts or in brand-new garb replacing that taken to the sea-bottom in some sunken ship.

“Men of culture; men who have known seafronts from Suez to Aden the long-way ’round and the boiling sea between.

“Men who have been 60 years at sea; men who were schoolboys the day before yesterday but who have beaten the Hun through the ice to Archangel and whose smiles, as they admit it, are still soft with youth.

“Men who have been torpedoed or shipwrecked or both; men who have been on the beach and who have held commands.

“Men with light in their eyes for things yet to be seen; men with eyes dead from having witnessed too much as shipmates fought off a Death that dived from the skies or a Death that crept over them in thirst upon the bitter waters….

“Grim and bitter, smiling and suave, foolhardy and thoughtful, pitted deep with stokehold grime or seamed still deeper by life and by suns over the seven seas—they are the faces of merchant seamen seen in Halifax this wartime.”

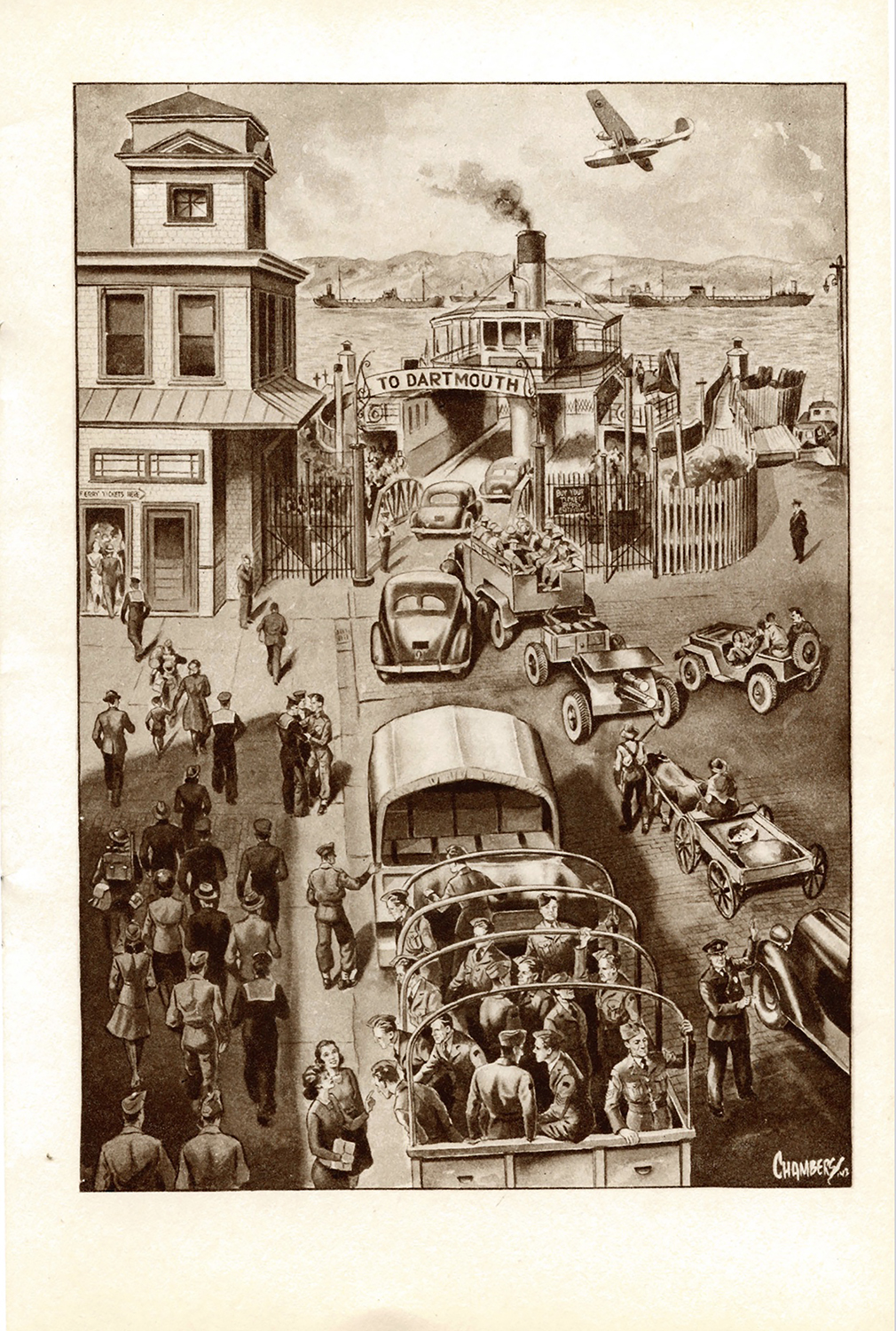

GATEWAY TO THE CITY

“Service trucks bound for the outposts, ox-carts headed home after market day—old and new clatter over the cobbles to the Dartmouth ferry. Business men and schoolboys, office girls and sightseers stream through this ancient gateway….

“Snub-nosed, bob-tailed ferries poke their way through passing convoys. Heedless, the homefolk and strangers crowd saloons and decks, sending a babel high over the throb of the engines.

“A sailor, home from the sea or headed for high venture, scans the water in silence, knowing the story of the listed, torpedoed freighter struggling to a safe anchorage, recalling another ship that will never come home.

“An airman glances at a passing plane, realizing it may be fresh back from a distant ocean patrol, a journey to a northern barrens base or perhaps from Britain, each trip a commonplace.

“The soldier, measuring with his eyes the drab, olive gun, wonders if the next convoy will be his, if that gun or its brother will go with him to the Flanders coast, to Italy or the Balkans.

“The dance tonight? The ships’ supplies so urgently needed? The unlearned algebra and the waiting class? The rate of Bren gun fire? How long will this gas keep a plane aloft? When will it be over and what will we do when we get home? Gossip? Where to find a place to live? Wonder if he is safe at Naples?

“The hurry, the questing haste, the thoughts of an ever-changing crowd, pausing its quarter hour at the city’s gate.”

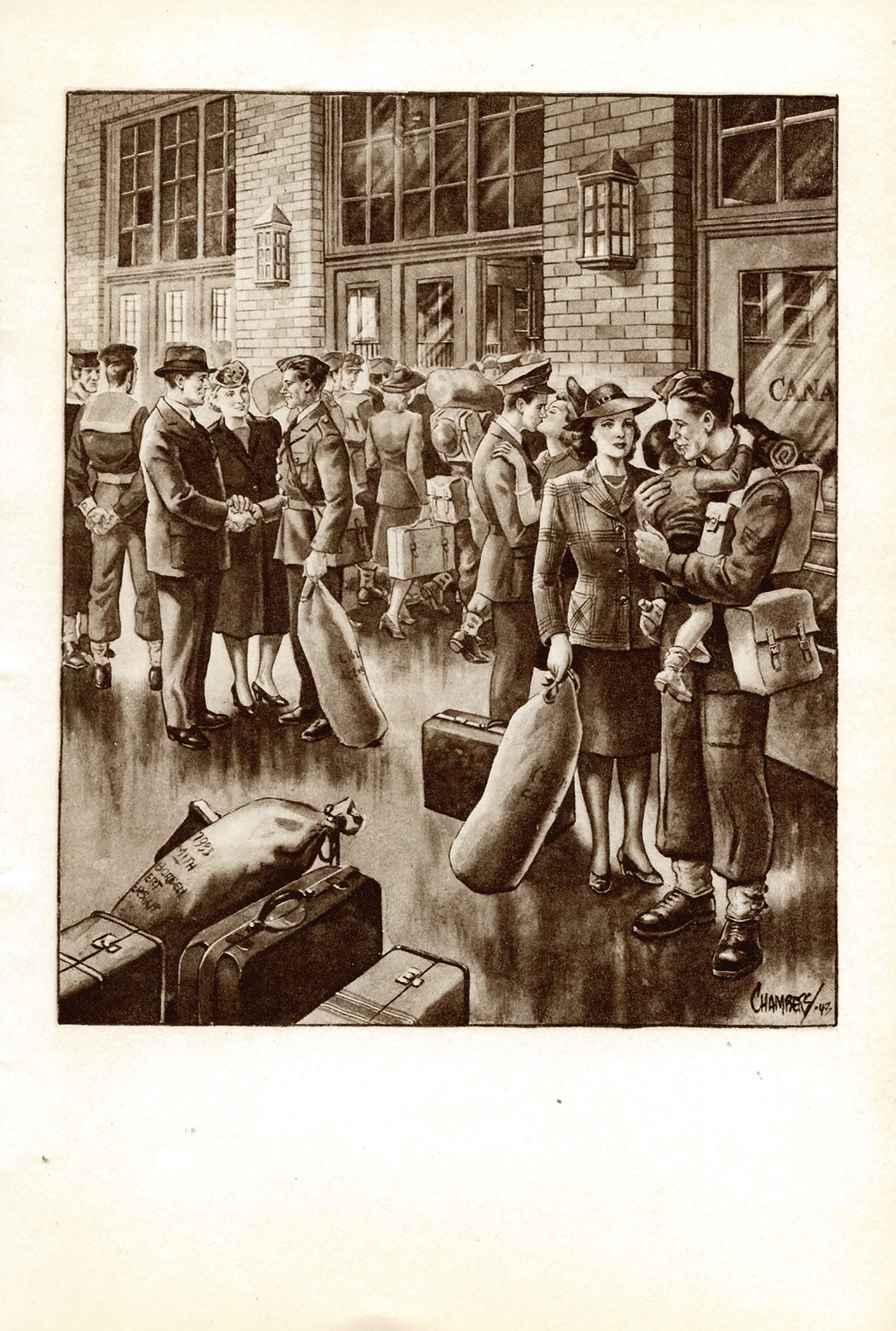

AN END AND A BEGINNING

“The hand on the big clock jumps a minute space; the sough of rushing air signals wheels freed for some far journey; the sun, mottling the walls, makes hopscotch patches on the gritty tiles; a thousand feet shuffle and grind, the whole space rings with the metallic beat of service boots and the snare-drum tap of women’s heels—pictures, poems in color and sound make and re-make themselves endlessly each hour. This railway station is where land passage across a continent ends, only to climax itself in new ventures in other elements, the sea and air. It is a starting place into war’s unknown; it is the ending place for those home from the battles.

“Furlough is over. Where next? What next? The Aleutians, Ceylon, Sicily, some new Dieppe? North Atlantic ice, the Sahara’s sand, Balkan mountains, a Labrador beach—to guard, to attack? Endless scouring of the ocean or sudden, seconds-long encounter in the heavens of another hemisphere? Death and glory—or glory and a safe return?

“If little be said, still less is to be said. What words has the boy bidding his father farewell, the wife seeing her husband depart, the mother for her son?

“What words can give body to thoughts born in times like these in places like this—Halifax terminal, the war’s beginning for so many at the war’s end for the fewer who come back.”

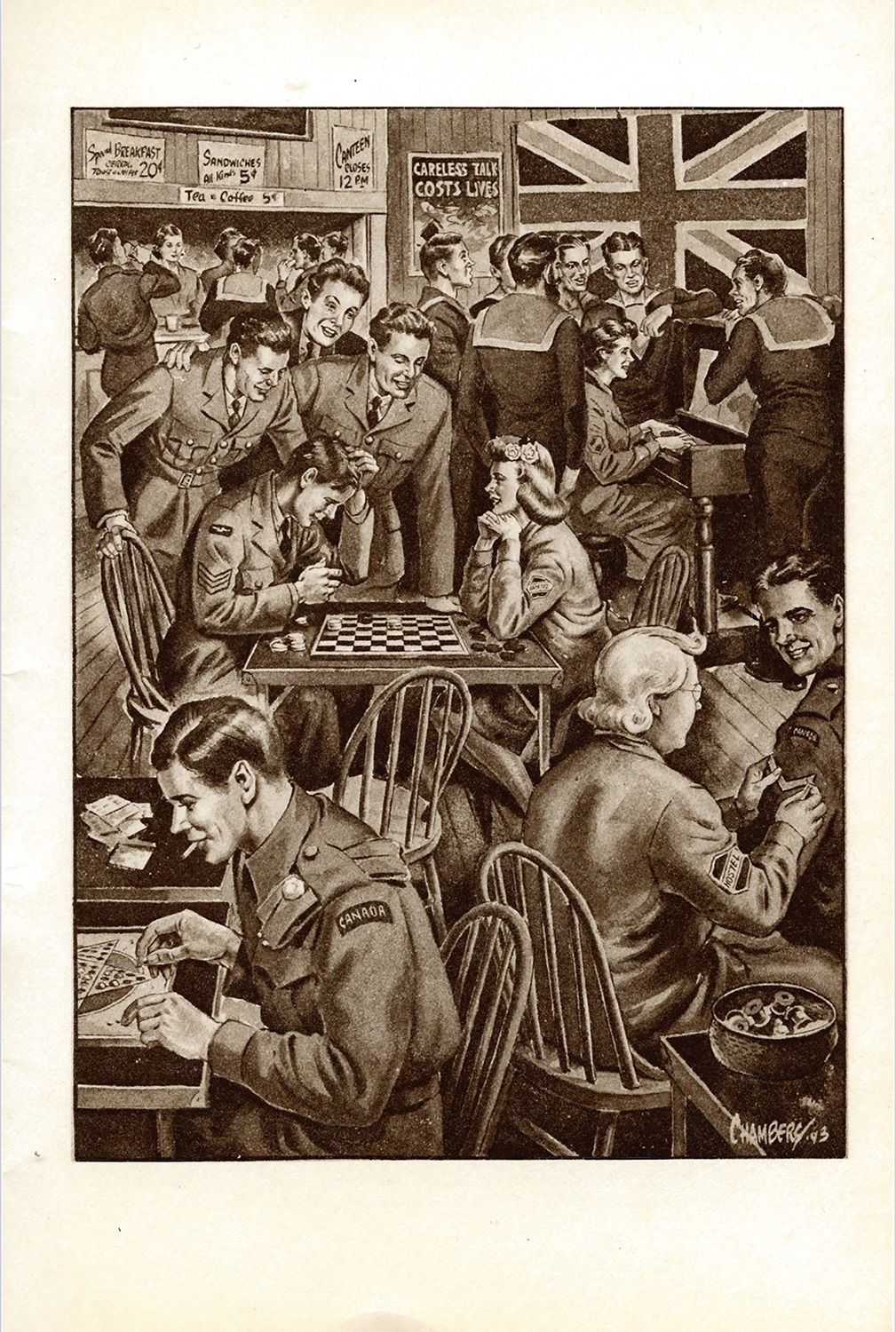

GENEROUS SERVICE

“It looks like fun—this working in hostels. It is, but it is something more. It involves a sacrifice which women of Halifax have cheerfully made each day since this war began. It means, for many of them, hours over hot stoves and steaming food counters after they have done a day’s work for their own families in their own homes. It means listening to soul-searching stories and giving counsel when there is the heartbreaking anxiety among many of the women themselves as they wonder at the fate of their own menfolk on the sea, in the air and on foreign soil.

“There are rewards. They come in the smiles that are brought to service men’s faces, the brief pleasures that can be given to them in their hours in the hostels—dancing, music, checkers, or just a passing word of cheer on the eve of embarkation, the thanks expressed in letters that come back from men overseas.

“The work is not spectacular, is heralded by no brass bands and yields no medals. It calls for the wisdom of age and the vivacity of youth, hours of planning and of hard work. These are given unquestioningly and constantly by Halifax women, a part of their share in winning this war.”

Advertisement