Public access to the Central Archives of the Special Administration of Justice (CABR) was limited until Jan. 1, 2025.

[Wikimedia]

War In Court, a project of the Netherlands-based Huygens Institute, released a list of the names online after a law restricting public access to the archive expired Jan. 1, 2025. The archives’ more detailed digitized files are expected to follow.

“This archive contains important stories for both present and future generations,” the institute said in a statement. “From children who want to know what their father did in the war, to historians researching the grey areas of collaboration.”

The institute is helping digitize 32 million pages of dossiers that include details on suspects and witnesses, as well as members of the Dutch Nazi party and some 20,000 Dutch citizens who enlisted in Nazi Germany’s armed forces.

Comprising files from the Special Criminal Jurisdiction, which began investigating suspected collaborators in 1944, the archive also contains the names of people acquitted. The expired law has been described as more restrictive than Italy’s, an Axis country whose wartime past is far more controversial than the Netherlands’.

Dutch Jews board a train bound for the death camp at Auschwitz.

[Rudolf Breslauer/Wikimedia]

Hans Renders, professor of history at the University of Groningen, told the BBC that only about 15 per cent of collaboration cases went to court and around 120,000 were dismissed. “So, if a name appears in the [archive], it is not certain that the person was ‘wrong.’”

A planned online release of the first eight million pages of detailed scans was postponed after the Dutch data protection authority intervened. All documents are expected to be digitized by 2027, but no date has been set for their formal release.

People with a research interest, including descendants, journalists and historians, have been able to submit requests to consult the actual files at the national archives. Now the general public can do so, too.

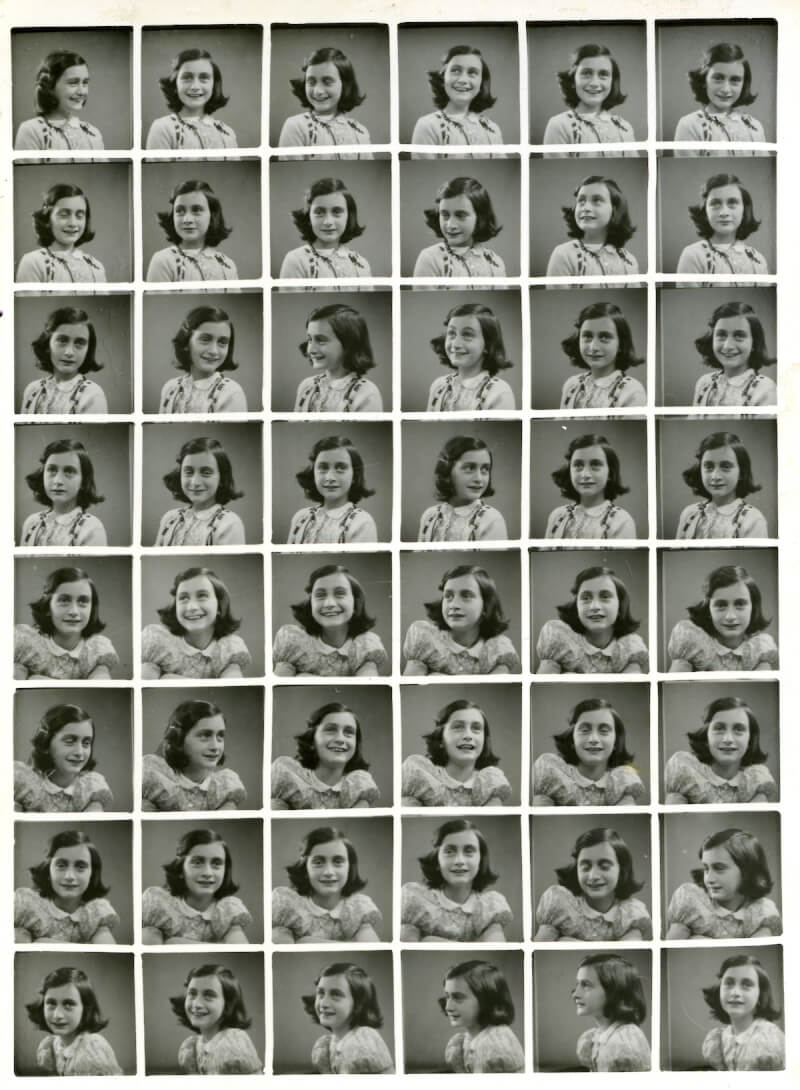

A young Anne Frank posed for these photos in a department store photo booth in 1939.

[Wikimedia]

Who betrayed her family remains a mystery—and still a sensitive topic.

The forces of Nazi Germany invaded the Netherlands in May 1940, beginning five years of brutal occupation during which at least 106,000 Dutch Jews were robbed of their property and belongings and transported to death camps at Auschwitz and Sobibor.

The identification and roundup of Dutch Jews was largely enabled by the efforts of a Dutch public servant, Jacobus L. Lentz, head of the Population Registration Office in the Hague.

The history is still fresh in the Netherlands and throughout much of Europe, where a total of six million Jews were systematically killed in what the Nazis dubbed the “Final Solution.” Another six million Roma, political foes, people with disabilities and other minorities across Europe died in Nazi gas chambers and by other means.

The most famous of the Netherlands’ wartime Jews was to be Anne Frank, the young girl whose diary chronicled two years in hiding before she and her family were outed to authorities. Frank, only 15, died with her sister in a concentration camp in 1945.

A memorial to Anne Frank and her sister Margot stands at the former Bergen-Belgen site where they died in a typhus epidemic in Germany.

[Wikimedia]

Amsterdam-based publishers Ambo Anthos ceased printing and recalled the 2022 book The Betrayal of Anne Frank: A Cold Case Investigation after an outcry over its findings. In an email to Canadian author Rosemary Sullivan and the investigators who spent six years gathering evidence, it said their work needed another look.

“A more critical stance could have been taken here,” wrote the publisher’s director, Tanja Hendriks. “We await the answers from the researchers to the questions that have emerged and are delaying the decision to print another run.

“We offer our sincere apologies to anyone who might feel offended by the book.”

The team of historians and investigative experts said it’s likely Arnold van den Bergh, a Jewish notary in Amsterdam, gave up the Franks to save his own family. The accusation spawned a wave of criticism from others close to the story who contend there’s not enough evidence to reach such conclusions.

van den Bergh was a member of the city’s Jewish council, which confoundingly implemented Nazi policy in Jewish areas. The council was disbanded in 1943 and many of its members were said to have been sent to concentration camps.

But the research team assembled by Dutch media producer Pieter van Twisk and headed by an ex-FBI agent discovered van den Bergh was not sent to a camp and instead continued living in Amsterdam.

The Netherlands’ population was 8.7 million, making just under five per cent of the country suspected collaborators.

The team acknowledged it had struggled with the revelation that another Jew was possibly the betrayer, but said it found evidence suggesting Otto Frank, Anne’s father, knew van den Bergh had given them up and kept it secret.

The investigators found a copy of an anonymous note sent in 1945 to Otto, the only family member to survive the Nazi concentration camps. It identified his betrayer as van den Bergh, who reportedly died of throat cancer in 1950.

Anne’s father turned the note over to a Dutch detective who investigated in 1963, but the detective dismissed it.

David Barnouw, author of the 2003 book Who Betrayed Anne Frank?, was among several Dutch historians who voiced concerns over the findings by van Twisk’s team. Barnouw said he had initially identified van den Bergh as a suspect, but later ruled him out because he found no evidence of his involvement beyond the note.

Emile Schrijver, director of Amsterdam’s Jewish Cultural Quarter, told The New York Times the evidence is “far too thin to accuse someone.”

The question remains whether the opening of the archives and making it searchable and accessible to the wider public will help solve the mystery, and others like it.

According to the Dutch central statistics bureau, in 1939—the year the Second World War broke out—the Netherlands’ population was 8.7 million, making just under five per cent of the country suspected collaborators.

While the vast majority of those named are dead (the database website says listees believed still alive do not appear online), the move after so many years is certainly not without controversy in the Netherlands for several reasons, not the least of which are concerns among relatives over what they might disclose.

“I am afraid that there will be very nasty reactions,” said Rinke Smedinga, whose father was a Dutch Nazi Party member and worked at a deportation camp.

“You have to anticipate that,” he told the Dutch online publication DIT. “You should not just let it happen, as a kind of social experiment.”

“The fact that relatively few were imprisoned probably tells us as much about post-war Dutch society as it does about the wartime facts.”

The Dutch government in wartime exile developed laws to prosecute suspected collaborators once there was peace; some 156,000 faced varying forms of punishment:

- About 16,000 people were convicted by special courts of justice, which had the authority to impose life sentences or the death penalty;

- some 50,000 were convicted by tribunals, which could impose sentences of up to 10 years internment;

- around 90,000 cases were settled administratively, often involving disenfranchisement and supervision;

- and 329,000 cases were settled without prosecution and dismissed due to lack of evidence, the suspect’s death, or other reasons.

“The fact that relatively few were imprisoned probably tells us as much about post-war Dutch society as it does about the wartime facts,” Royal Holloway, a history professor at the University of London, told NBC News.

Holloway called the archive an “extraordinary resource, and one that is very timely in terms of the Dutch debates about the war and levels of collaboration.”

Collaborators and moffenmeiden (‘Kraut girls’) are rounded up and publicly humiliated by Dutch Resistance following the liberation.

[Willem van de Poll/Wikimedia]

It was under the purview of the Dutch justice ministry until 2000, when it was transferred to the national archives.

An archives official could not confirm the exact number of CABR requests received so far, The Brussels Times reported, but they acknowledged that the reading room would be busy for a while. The number of available reading room spots was recently increased from 108 to 140, with 61 reserved for people seeking CABR documents.

“Openness of archives is crucial for facing the effects of [the Netherlands’] difficult shared past and to process it as a society,” Culture Minister Eppo Bruins wrote in a Dec. 19 letter to the Dutch parliament.

Said national archive director Tom De Smet: “Collaboration is still a major trauma. It is not talked about. We hope that when the archives are opened, the taboo will be broken.”

Advertisement