This quartet of Izzy dolls is dressed as UN peacekeepers. [Isfeld Family Collection]

How Izzy dolls comfort children in hot spots around the world

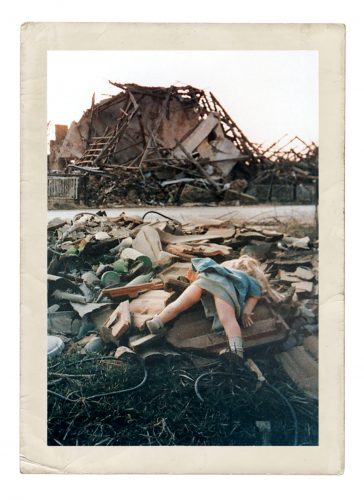

While on patrol in Croatia in the fall of 1992, Master Corporal Mark Isfeld of 1 Combat Engineer Regiment spotted a figure lying prone on the rubble of a house that had been hit by artillery in the civil war that followed the breakup of the former Yugoslavia.

When he went to investigate he found it was not a child, as he had feared, but an abandoned doll. He took a photo of it and showed it to his mother, Carol Isfeld, when he was visiting her on his return to Canada.

“Look,” he said. “A little girl has lost her doll and a doll has lost her little girl.”

That comment and her son’s obvious compassion for the children he was encountering on peacekeeping missions inspired her to knit a bunch of very small woollen dolls.

Having returned to Croatia on his third peacekeeping mission in two and half years, Isfeld was surprised to receive a package from his mother containing 22 little woollen dolls, each stuffed with cotton batting and about 12 centimetres in length. The boy dolls had a peacekeeper’s blue helmet while the girls had braided hair. They were small enough to fit in his pocket when he went out on patrol and he could give them to children he met who were in need of a little comfort.

In the fall of 1992, Master Corporal Mark Isfeld (above) saw a pile a debris (below) in Croatia with what he feared was the body of a child on the top. On closer inspection, he saw that it was a doll. This became the inspiration for the original Izzy dolls (below). [Isfield Family Collection]

As a combat engineer, Isfield’s expertise was in clearing and defusing landmines. On June 21, 1994, he was guiding a LAV III armoured personnel carrier down a trail he had cleared of mines the previous day near the village of Kakma, when the vehicle hit a tripwire which triggered a roadside bomb that exploded. Isfeld died of his wounds shortly afterward.

In tribute to him, members of his regiment continued to give out the dolls that Carol Isfeld kept on making and sending, calling them “Izzy dolls.”

She recruited some other women around her home in British Columbia and continued to make the dolls for Canadian engineers and other peacekeepers wherever they were deployed.

Carol Isfeld eventually put the pattern on the Internet and a network of women formed to knit and crochet the dolls. She established a copyright on the dolls and declared that they could never be bought or sold for profit.

Soon volunteers across Canada were joining up.

Izzy Dolls. [CWM/ 19980071-005]

In Perth, Ont., 85 kilometres south of Ottawa, Shirley O’Connell was struck by images of the 2004 tsunami that devastated Indonesia and wanted to do something. When she heard about the Izzy dolls, she made a connection.

She contacted Carol Isfeld and asked if the Izzy dolls could be made to help children in natural disasters. Isfeld agreed and O’Connell began making dolls.

“I think I’ve made somewhere around 2,000 dolls,” said O’Connell. “I followed the pattern at first but then I changed it. Instead of being a peacekeeper with a blue helmet, “For instance, I made a Mountie. My late husband was in the RCMP.”

O’Connell and the Isfelds soon developed a long-distance friendship. When Carol and Brian Isfeld died in 2006 and 2007 respectively, the Isfeld family asked O’Connell to take over co-ordination of the Izzy dolls distribution. She soon became known as the Izzy Doll Mama.

She broadened the range of who should receive the dolls. She was moved by the 2014 shooting in Moncton, N.B., when three officers were killed and two others wounded. “We sent some down there to help children who were suffering.”

She has sent them to kids affected by other terrible events in Canada. “We sent some to Fort McMurray after all those people lost their homes in the wildfire.” This year she sent some to Nova Scotia after the shooting and arson rampage that left 22 people dead.

[19980071-003]

“We have helped out at other natural disasters, working with the Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART). We sent a bunch to Haiti after the hurricane. We used brown wool for the faces that time,” said O’Connell.

International relief organizations such as ICROSS Canada, which provides medical and educational supplies for those living in poverty in the world’s poorest countries, and Health Partners International Canada (HPIC), which sends medical supply packages to health care workers in developing nations, became major recipients. HPIC uses the dolls as packing material instead of Styrofoam.

“A little girl has lost her doll and a doll has lost her little girl.”

They have also sent Izzy dolls with the Orbis Flying Eye Hospital, a state-of-the-art aircraft that has its own operating room and trains eye doctors around the world. The

volunteers knit little dolls with eye patches that can be removed.

When dolls are sent to Africa, they are called comfort dolls since there are no Canadian soldiers to explain who Izzy was.

Mark Isfeld’s mother Carol stands in front of a statue dedicated to her son in Peacekeeper Park in Calgary. [Isfeld Family Collection]

The network grew, reminiscent of the women who knitted socks and scarves for servicemen during the two world wars.

Lorena Macklin, who has a farm vegetable store near Sarnia, Ont., got the pattern and distributed it to various church groups shortly after Corporal Brent Poland of Sarnia was killed in Afghanistan on April 8, 2007. Macklin had people bring the dolls to her store.

“She was receiving hundreds of dolls,” wrote Don Poland, Brent’s father, in response to Legion Magazine’s request for Izzy doll stories. In the early summer of 2007, he drove the dolls to the depot in Toronto to be shipped to Afghanistan.

“I can’t remember for sure [how many there were] but on that trip my Honda Accord had at least six big plastic drum liners full of dolls,” wrote Poland. “The trunk was jammed full and the entire back seat area was packed with bags of dolls. The folks at the depot said it was one of the largest donations they had ever received.”

O’Connell is assisted by retired lieutenant-colonel Ken Holmes of Fitzroy Harbour, Ont., near Ottawa. He is the historian for the Canadian Military Engineers Association.

“There is no such thing as a standard operating procedure,” said Holmes. “When she has a load to send out, I co-ordinate with the military to see how we can get them where they are going.

Shirley O’Connell of Perth, Ont., has come be known as the Izzy Doll Mama after taking over the collecting of Izzy dolls from the Isfeld family. [Ottawa Citizen]

“When we get a request from one of the engineering units, I get in touch with the home base and see whether they might take them along when they are flying a resupply mission.

“For instance, there was an engineering unit with the recent peacekeeping mission to Democratic Republic of Congo. We had heard that they were visiting some orphanages. We were able to get a bunch of Izzy dolls to them. For a country in Africa, we try to send ones with black faces.

“We tried to use military missions to supply the soldiers but there are also other international agencies, such as the Red Cross or other organizations,” said Holmes.

A CAF member distributes Izzy dolls to children in war-torn Afghanistan in July 2006. [Isfeld Family Collection]

Carla Krens of British Columbia wrote that she had a personal interest in Mark Isfeld’s story. Her husband, Brigadier-General Jerry Silva, had attended the opening of Mark R. Isfeld Secondary School in Courtenay when he was colonel-commandant of the Canadian Military Engineers. Krens and Silva later became involved with 6 Field Engineer Squadron Museum in North Vancouver. The museum had an Izzy doll.

“That particular Izzy doll was poorly made and I took upon myself to knit a better one for display in our museum,” wrote Krens. “I liked it so much I wanted to do more, so I checked to see if there were still organizations that would take the Izzy dolls for distribution.”

She found HPIC. “I decided to knit 100 dolls in 100 days—and I did! No two are the same. Over time, I made the dolls smaller and smaller, with the finest wool and size-0 needles, so that the doll could fit into a tiny hand and give comfort. I was told by one soldier that he remembered seeing Izzy dolls in Afghanistan and how much the children appreciated them.”

The dolls proved popular with the soldiers themselves. David Panepinto of Edmonton recalled seeing them while he was deployed to Kandahar, Afghanistan, with the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment attached to 3rd Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment, in 2008-09. He recalled giving away a few dolls along with pens and paper, which were always popular among the children.

“Seeing kids was a good sign on foot patrol. It usually meant there would be no action in the immediate area,” said Panepinto. “When kids weren’t where they usually were, we knew we would probably be in contact at any time. That was the ‘absent of the norm, presence of the abnorm’ we were told to look for.”

Somehow one of these Izzy dolls ended up in his barracks box and was shipped back to Canada when he returned. “I still have it and plan to pass it on to children of my own or donate it to the Canadian War Museum should children not be in my future,” he said.

“We had stopped sending the dolls to Afghanistan after it got too dangerous [when the Canadian contingent moved to Kandahar Province],” said O’Connell. “The last thing we would want would be for a soldier to get killed while giving out the dolls. Thank goodness, it has never happened.”

A Canadian officer distributes Izzy dolls to children at the Tulizeni Centre orphanage in the Democratic Republic of Congo in March 2017. [Canadian Armed Forces]

For the National Day of Honour for the Afghanistan mission held on Parliament Hill on May 9, 2014, a relay team of 19 ill or injured soldiers walked a marathon from CFB Trenton to Ottawa. With them, they carried a baton containing the last Canadian flag to fly over International Security Assistance Force headquarters in Kabul.

When they reached Perth, the Perth-upon-Tay Branch of The Royal Canadian Legion held a reception for the team and invited O’Connell. Of course, the soldiers knew the story of the Izzy dolls and were glad to meet her.

“I met a woman soldier there who told me she had an Izzy doll. It meant so much to her after she had been wounded,” said O’Connell. “She said when the pain was bad, she just bit down on the doll until the pain subsided.”

The legacy of the Izzy doll continues in many ways, more than 25 years after the death of Mark Isfeld.

The Encounters with Canada program, run by Historica Canada in Ottawa, uses partially finished Izzy dolls during its Remembrance Week program. Students attend a workshop where they learn the story of the dolls and then finish making them.

Shortly before the 2020 pandemic hit earlier this year, Holmes was liaising with the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Que., to supply the iconic dolls for educational packages that the museum was loaning to schools.

A new generation is being introduced to Izzy dolls.

Advertisement