HMCS Kootenay leads a convoy of ships escorting HMY Britannia into Toronto during Queen Elizabeth II’s royal visit in 1959. [DND]

The worst peacetime disaster in Canadian naval history occurred 51 years ago this week when nine crew were killed and another 53 injured in an explosion and fire aboard HMCS Kootenay.

The engine-room accident on Oct. 23, 1969, marked the last time Canadian service personnel were required to be buried overseas and it helped bring about sweeping changes to shipboard fire-prevention and firefighting systems.

The Restigouche-class destroyer was part of a task group that included the aircraft carrier HMCS Bonaventure and eight destroyer escorts sailing in European waters. The group was homeward bound, crossing the English Channel, when Kootenay and HMCS Saguenay broke off to conduct sea trials 320 kilometres off Plymouth, England.

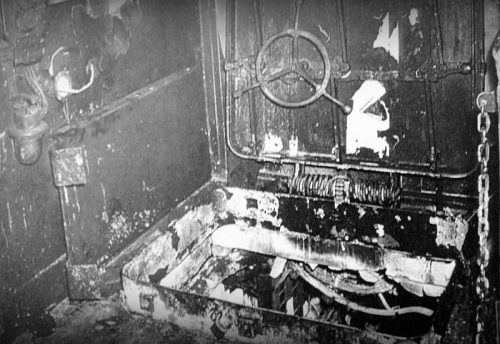

Fire damage to the engine room access hatch aboard HMCS Kootenay. [DND]

“We heard a whoosh and then there was a wall of flame coming from the starboard gearbox,” recalled Able Seaman Allan (Dinger) Bell, one of only three below to survive the explosion. “It was immediately followed by a blast of fire that whooshed all through the engine room.”

Seven were killed in the blast; two more died as a result of the ensuing fire. By the time the fire was brought under control hours later, 53 were injured.

“We were all on fire,” said Bell, who had third-degree burns over half his body. “The ventilation on the ship was such that the intake vents sat overtop of the gearboxes, and the exhaust fans were behind us.

“As the air was blowing in, it was sucking the fire and all the oil right to us.”

The flames burned their flesh; black, oily smoke filled their lungs. The only way out was a five-metre ladder.

“Everybody wanted up the ladder and they were going over each other’s backs,” said Bell. “I got dragged down the ladder three times. Bodies dying on top of me, pulling me down, people going over your back, and everybody, like bowling pins, would fall. You’d get up and it would start again. There was nothing you could do.

“You’re on fire and your skin is falling off…and I knew that I was going to die.”

Alan Kennedy survived the blast with severe burns to 30 per cent of his body, along with smoke inhalation, chronic pain syndrome and PTSD.

“The climb was only seconds but seemed like an eternity,” said Kennedy. “The only thing going through my mind was a feeling of sadness that I was going to die and not be able to see my three-month-old infant son.”

Those who could mustered on the quarter deck, gathering firefighting equipment and co-ordinating a rescue. Most of the firefighting equipment, however, was inaccessible or destroyed by the fire.

“When the explosion happened, you lost almost a quarter of your firefighter equipment right there,” said survivor Ray Desrosiers. “The rest of us were kind of left without access to the firefighting equipment that we needed to fight the fire.”

Nobody could see where they were going, he said. Men were crawling on their hands and knees.

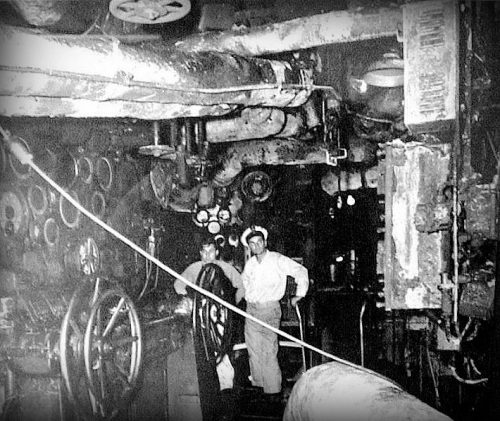

A Kootenay crewman alongside the blackened control console at the forward end of the ship’s engine room. [DND]

The heat was so intense that a bulge began to form in Kootenay’s starboard side. By the time the flames were extinguished more than two hours later, said Bell, the ship was badly burned and the engine room was destroyed.

Kootenay was taken under tow to drydock in Plymouth, where Englishman Robert Twitchin and other members of a six-man team of civilian engineers removed the propellers. As part of the investigation, they also dismantled the ship’s drive trains, gearbox and bearings.

“When we first got down into the Kootenay engine room and saw the extensive destruction, including the ripped-open starboard gear case cover and the damage from the exploding lubricating oil vapour, it was truly shocking,” Twitchin told The Lookout, CFB Esquimault’s base newspaper.

“The whole compartment had been blackened by the explosion and fire with lots of debris all around, and there was an overwhelming burnt smell throughout the ship.”

HMCS Kootenay at sea. [DND]

The refusal to repatriate the remains and to limit funeral attendees angered many. Sandra Amos, widow of Leading Seaman Pierre Bourret, said she was told she could take only one person on the government dime.

“My husband’s parents were not allowed to go from Quebec,” she said. “They were not allowed to go to their son’s funeral. To exclude a man’s family from his funeral service…it still really, really bothers me.”

It would be the last time Canadian service personnel killed overseas would not be brought home for burial. Parliament changed the policy soon after the tragedy.

The probe and preparations for the transatlantic voyage home, meanwhile, took weeks, during which some crew were left aboard the damaged vessel while others were taken ahead aboard Bonaventure.

Just a few days outside Halifax, Petty Officer Lewis Stringer, who was suffering from smoke inhalation, died of a heart attack aboard the carrier, the ninth victim of the explosion and fire, and the only one to be buried on Canadian soil.

Conditions aboard Kootenay were less than ideal for the crew left behind.

“For the next three weeks I lived in 3 Mess…on that horrible, dark, burnt, foul-smelling coffin of a ship while someone in Canada decided what to do with the remaining crew,” said Jim Stutely. “To me that was a total disgrace, to say the least.”

Twitchin said it was evident from the start of the investigation what had gone wrong.

“Just by looking at the shattered gear case cover, it was immediately clear there had been no monitoring of…bearing temperatures,” he said.

Both covers were fitted with blanking plugs instead of thermometers, and both were caked in old paint, suggesting they had not been removed regularly.

“It would have been impossible for engine room watchkeepers to monitor a bearing overheating,” said Twitchin. “In essence, the ship was running blind.”

A board of inquiry would publicly conclude the explosion was caused by the fact that insert bearing shells in the starboard gearbox had been installed backwards.

“The explosion is considered to have been caused by the spontaneous ignition of oil and oil vapour through the gross overheating of the high speed pinion bearings,” the report said.

“The cause of the overheating was the incorrect fitting of the insert bearing shells, which resulted in the direct oil supply being completely cut off.”

Kootenay was taken on an 11-day ocean tow with a skeleton crew of 60-plus aboard, arriving in Halifax on Nov. 27, 1969.

A guard is framed by a saluting officer at the Canadian Peacetime Sailors’ Memorial in Halifax during a ceremony marking the 50th anniversary of the HMCS Kootenay explosion and fire on Oct. 23, 2019. [Andrew Vaughan/The Canadian Press]

The tragedy marked a turning point in Canadian naval policy and attitudes surrounding fire prevention and damage control, resulting in major changes, including more onboard equipment placed in key locations throughout ship; better firefighting and damage control training; and more frequent and vigorous equipment inspections and maintenance.

Ship designs were modified, creating three exits from all engine spaces and at least two hatches in every area aboard ship. Ships’ ladders are now steel instead of the aluminum of the day, and automated systems can isolate sections of the ship in emergencies.

On Oct. 23, 2002, the RCN opened a new firefighting facility at CFB Halifax, naming it Damage Control Training Facility (DCTF) Kootenay.

The tragedy and the crew’s response inspired public support that helped expedite creation of the Canadian bravery decorations.

Hence, the first Crosses of Valour were awarded posthumously to two Kootenay crewmen, Stringer and Chief Petty Officer Vaino Olavi Partanen. The Star of Courage was awarded to Sub-Lieutenant Clark Reiffenstein (posthumously) and Petty Officer Clement Bussiere. The Medal of Bravery was awarded to Chief Petty Officer 2nd Class Robert George and Petty Officer 1st Class Gerald Gillingham.

The board of inquiry praised the actions of Kootenay’s crew, noting many rushed to the scene of the explosion “without regard to personal safety to save lives and tend to men trapped in isolated places.” It concluded that Kootenay’s 12 officers and 237 seamen “behaved in meritorious fashion” to save the ship.

Those killed were: Leading Seaman Pierre S. Bourret; Leading Seaman Thomas Gordon Crabbe; Petty Officer Eric George Harman; Ordinary Seaman Michael Alan Hardy; Chief Petty Officer Vaino Olavi Partanen; Chief Petty Officer William Alfred Boudreau; Leading Seaman Gary Wayne Hutton; Ordinary Seaman Nelson Murray Galloway; and Petty Officer Lewis J. Stringer.

Advertisement