8 myths of Black service in the Canadian Expeditionary Force—and the actual realities they faced

In the fall of 1915, Lieutenant-Colonel Walter H. Allen, the white commander of the 106th Overseas Battalion (Nova Scotia Rifles), met with a Black Baptist minister, Reverend William White, and made a promise he couldn’t keep.

“I told him if he would get in touch with the coloured men throughout Nova Scotia, and raise enough for a platoon, I would take this platoon into my Regiment,” Allen wrote to military authorities in Halifax.

White said he’d get busy, but by the time Allen followed up on Dec. 14, 1915, the commander had received only a half-dozen or so names. Meanwhile, word had come down from Ottawa that there were to be no racial distinctions on enlistments.

“As soon as this became known, several white men who had been about to sign on, refused to do so if coloured men were to be admitted into the Regiment,” Allen wrote to regional headquarters. “Personally, I think coloured men should do their share in the Empire’s Defence, and I believe that some of them would make good soldiers.

“Still, if I had my choice I would prefer white men…and I would feel very loath to risk the experiment of taking on negroes when plenty of white men were available.

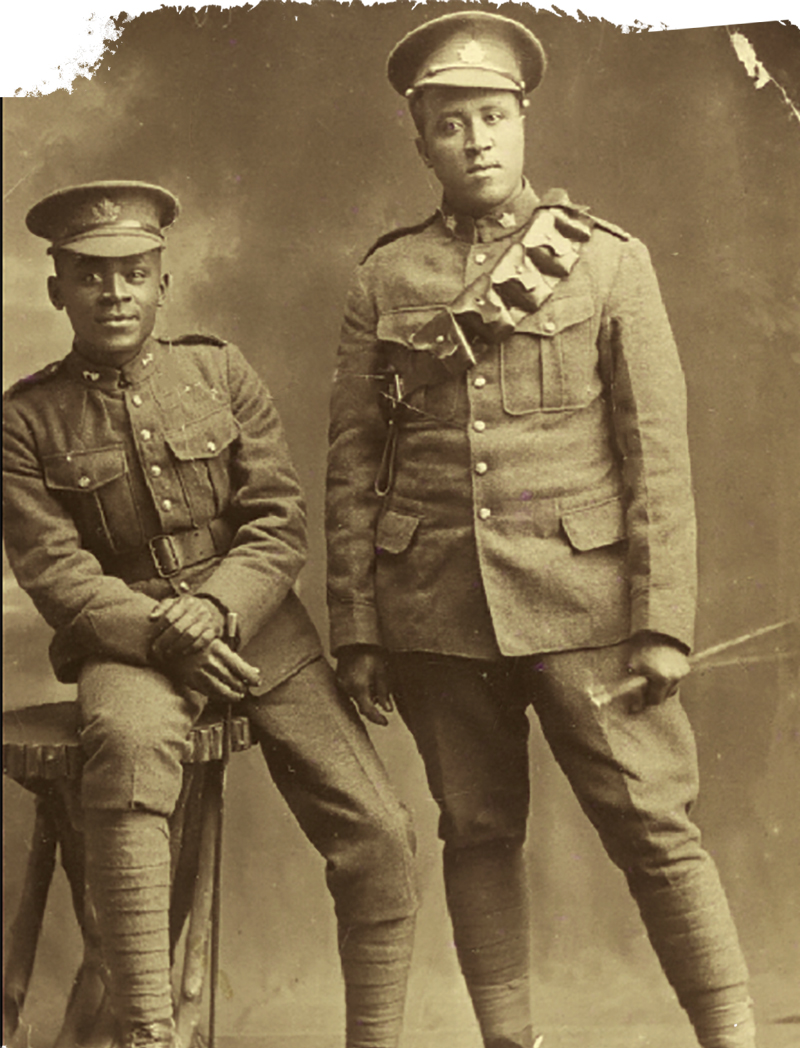

Private Charlie Kelly of Ingersoll, Ont., pitched for the No. 2 battalion baseball team, scoring a run and throwing a 2-1 gem against Orpington Hospital in front of King George V in September 1917. He transferred out to an integrated support company and served in France, Belgium and occupied Germany. Reverend William White, an honorary captain, was No. 2’s only Black officer.

“Neither my men nor myself, would care to sleep alongside them, or to eat with them, especially in warm weather. A white man’s appetite is a peculiar thing.”

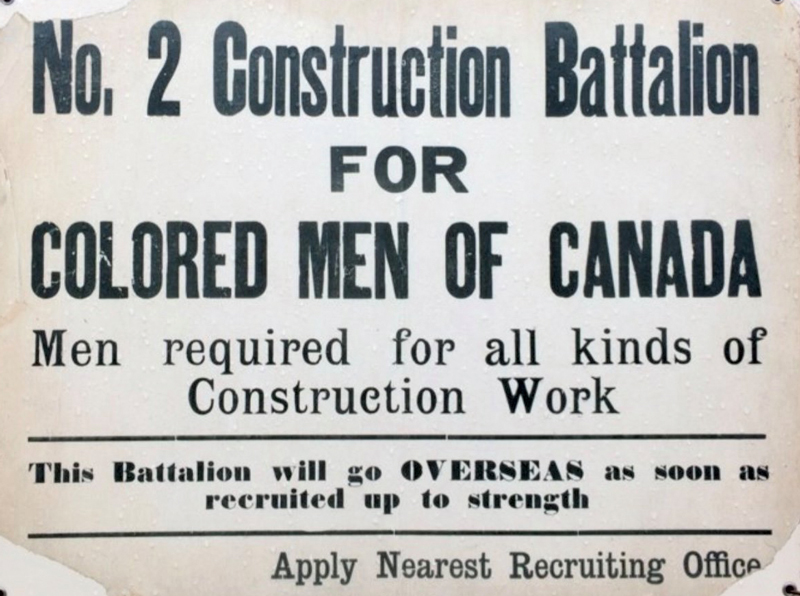

And therein lie the first myths surrounding No. 2 Construction Battalion, Canada’s most celebrated segregated Black unit: that most Blacks somehow wouldn’t make good soldiers, that the proportion of Blacks willing to enlist was small and that racism was not widespread in the Great White North.

“The treatment received by ‘visible’ Canadians did not originate with the military,” James Walker, a leading scholar of Canadian race relations and Black history at the University of Waterloo, wrote in a 1989 paper.

“Recruitment policy and overseas employment were entirely consistent with domestic stereotypes and ‘race’ characteristics and with general social practice in Canada…. Racial perceptions were derived, not from personal experience, but from the example of Canada’s great mentors, Britain and the United States.”

I would feel very loath to risk the experiment of taking on negroes when plenty of white men were available.

[CWM/19920166-2273]

The desire among Black Canadians to join the fight was nevertheless strong, but so was white resistance to their service.

In Saint John, N.B., 20 Black volunteers couldn’t find a battalion to take them. On the West Coast, an officer in Victoria said white battalions didn’t want Black recruits.

Concerns with such attitudes and practices emerged at least as early as November 1914, when Arthur Alexander of North Buxton, Ont., told Militia and Defence Minister Sam Hughes that “the coloured people of Canada want to know why they are not allowed to enlist in the Canadian militia.

“I am informed that several who have applied for enlistment in the Canadian expeditionary forces have been refused for no other apparent reason than their colour.”

On Sept. 7, 1915, George Morton of Hamilton wrote Hughes “on a matter of vital importance to my people (the coloured), in reference to their enlistment as soldiers.”

Morton wanted to know if Ottawa had an official policy on enlistment of “coloured men of good character and physical fitness.

“A number of coloured men in this city, who have offered for enlistment and service, have been turned down and refused, solely on the ground of colour or complexioned distinction,” he wrote.

“A number of leading white citizens here, whose attention I have drawn to this matter, most emphatically repudiate the idea as being beneath the dignity of the Government to make racial or colour distinction in an issue of this kind.

“They are firm in their opinion that no such prohibitive restrictions exist.”

Hughes’ directive confirming that stance was issued shortly afterward. But it didn’t seem to matter. By Dec. 31, at least 200 Black Canadian volunteers had been rejected.

The issue of Black enlistment was debated in Parliament before the chief of the general staff issued a memorandum on April 13, 1916, citing what he called the facts.

“The civilized negro is vain and imitative,” wrote Major-General Willoughby Gwatkin, head of the militia. “In Canada he is not being compelled to enlist by a high sense of duty; in the trenches he is not likely to make a good fighter.

“Not a single commanding officer in the Military District No. 2 is willing to accept a coloured platoon as part of his battalion.”

Ironically, it was Gwatkin who came up with the idea of a Black labour unit.

Both Prime Minister Robert Borden and British authorities approved it, along with a proposal to break with the practice of the day and allow the unit to recruit countrywide. The all-Black battalion, based initially in Pictou, N.S., was authorized on July 5, 1916.

Allen’s 106th eventually took on 18 Blacks, but most were reassigned to other units once overseas. Ultimately, more than 1,300 Black recruits would serve in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Fewer than 400 of them were conscripted.

“The experience of visible minorities in World War I illustrates the nature of Canadian race sentiment early in this century,” Walker wrote.

“Most abruptly, it demonstrates that white Canadians participated in the Western ideology of racism. This was true not only in the general sense of accepting white superiority, but in the particular image assigned to certain people which labelled them as militarily incompetent.”

From his pulpit in Zion United Baptist Church in Truro, N.S., historians say White—the son of former slaves—was in the process of achieving “almost mythic status” as the “universally recognized leader” of Nova Scotia’s Black community.

A champion of Black enlistment, he would serve as No. 2’s—but not the CEF’s—only Black officer, bearing the honorary rank of captain as its padre.

Runchey’s coloured corps, a light-infantry unit, saw action in some of the war’s best-known battles.

Jamaican-born William Gale (above) served in No. 2. His son Thamis (bottom), a Second World War veteran, spent years documenting the contributions of Black soldiers in Canada. [Black Canadian Veterans Stories]

[Black Canadian Veterans Stories]

Kathy Grant, a historian who has dedicated her career to documenting Black military service in Canada, says about eight Blacks served as officers in the CEF and Royal Flying Corps during the First World War—including one infantry officer and two pilots.

Much has been written about No. 2 Construction Battalion in particular, but many myths and misconceptions surrounding the unit and early Black military service in Canada persist. Here are eight of them.

Myth #1: Blacks didn’t serve in Canadian military units before the First World War.

Walker notes that contrary to this belief, Black and Indigenous Peoples “had a proud record of military service prior to Confederation.”

Robert Reuben Runchey, a tavern keeper from Jordan, Upper Canada, outside present-day Lincoln, Ont., was tapped to lead what became known as Captain Runchey’s Company of Coloured Men in July 1812.

Black settler Richard Pierpoint, who had served as part of the Loyalist Butler’s Rangers during the American Revolutionary War, had petitioned the commander of British forces in Upper Canada, Major-General Isaac Brock, to form a militia corps from Black settlers in the Niagara peninsula.

Brock initially turned down Pierpoint’s request. But by mid-summer, he was desperate for volunteers, so adopted it and assigned Runchey, a former officer in the 2nd Flank Company of the 1st Lincoln Regiment of Militia, to assemble a unit. Pierpoint enlisted as a private. He was 68 years old.

Runchey’s coloured corps, a light-infantry unit, saw action in some of the war’s best-known battles—including Queenston Heights, where they helped recapture the Redan Battery after Brock was killed.

The coloured corps later built a single-gun battery at Mississauga Point to harass ships resupplying Fort Niagara and fought multiple engagements throughout the Niagara region, the Battle of Fort George among them.

A couple of decades later, hundreds of Black militia men fighting in five companies helped put down the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837-1838.

In November 1857, an already-decorated Able Seaman William Hall of Horton’s Bluff, N.S., earned the Victoria Cross after he and another survivor of their ravaged gun crew maintained artillery fire until British forces breached the wall and ousted a band of rebels at the Shah Najaf mosque in Lucknow, India. He was the first Black person and first Nova Scotian to receive the VC.

In the late 1850s, hundreds of Black settlers moved from California to Vancouver Island. About 50 of them organized the Victoria Pioneer Rifle Corps, an all-Black volunteer force also known locally as the “African Rifles.” It was the first officially authorized militia unit in the West Coast colony.

Myth #2: The No. 2 Construction Battalion consisted only of Nova Scotians.

Barbadian-born infantry Sergeant Christopher Marshall stands alongside Trooper Brandie Simms of the Royal Canadian Dragoons. A Nova Scotia native, Simms was killed in action in October 1918.[Black Canadian Veterans Stories]

Actually, fewer than half the 595 soldiers who shipped out with No. 2 on March 28, 1917, were Nova Scotia-born.

Much of the Caribbean was part of the British Empire at the time and many Trinidadians, Jamaicans and Barbadians felt compelled to volunteer. Americans, too, saw opportunity north of the border as Canada mobilized for war in Europe.

No. 2 offered Black volunteers opportunities they had started to believe were beyond their reach. Nearly 200 American-born soldiers ended up serving in No. 2. With 43 volunteers, Barbados had the largest representation from the British West Indies.

Myth #3: Blacks served only in support roles with No. 2.

By the war’s end, 796 soldiers had served in No. 2, but 400-500 more managed to enlist in infantry and other units. About 100 saw front-line action on the ground or in the air. A high percentage of Black soldiers at the front were wounded; at least 35 serving with the CEF were killed in action.

Myth #4: Blacks wouldn’t make good soldiers.

There are many stories of courage and exceptional deeds by Black soldiers.

One of those was James Post of Ottawa, who at 17 had already been serving two years overseas when he earned a Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) for “conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty” during a 1917 attack at Passchendaele. He was a corporal in the 4th Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles.

“When his company was held up by rifle and machine gun fire from the vicinity of a ‘pill-box,’” said his citation, “he crept forward under a shower of enemy hand grenades and assisted a man on to the roof of the pill-box, which was then bombed and the garrison were captured.

“When all the officers had become casualties and the line was in danger of being driven in, with great coolness he held on to the ground gained and sent back valuable information on his own initiative. He set a magnificent example of courage and resource.”

Post, who went on to become a sergeant, had three older brothers who all served in non-segregated units: Patrick was a driver with the 25th Battalion (Nova Scotia Rifles); Montague was a decorated lance-corporal in the 1st Canadian Division who returned to action after he was wounded and gassed at the front and drummer Francis made it as far as England before a bad heart forced him back home.

Then there was Jeremiah Jones of East Mountain, N.S., who was already 58 years old by the time he reached the front with the Royal Canadian Regiment in February 1917 (he had told recruiters he was 38).

Two months later, the six-foot-six private crossed the bloody battlefield at Vimy Ridge and took an enemy machine-gun nest.

“I threw a hand bomb right into the nest and killed about seven of them,” Jones recalled years later. “I was going to throw another bomb when they threw up their hands and called for mercy.”

Jones ordered the half-dozen survivors out of their hole, then marched them at bayonet point back to Allied lines, carrying their weapon. He had them deposit the machine gun at the feet of his commanding officer and asked: “Is this thing any good?”

No. 2 harvested and processed lumber, built and maintained roads and railways, and operated and maintained water systems during much of the war. [Lt.-Col. D.H. Sutherland Collection/River John, N.S.]

His exploits earned him acclaim at home and abroad, but they remained the subject of debate from London to Ottawa for almost a century.

By Aug. 17, 1917, his hometown newspaper was celebrating Jones as “a patriot, brave, powerful and resourceful.” His commanding officer recommended him for a Distinguished Conduct Medal.

He received nothing and it wasn’t until the 1990s that a campaign was launched to award Jones a medal, more than four decades after he died. It was an uphill battle.

Jones was finally recognized on Feb. 22, 2010, when Ottawa posthumously awarded him the Canadian Forces Medallion for Distinguished Service, a 1989 creation intended for civilians. It was no DCM, but it was recognition.

“Jeremiah Jones put the lie to perceptions of the day,” author, historian and later senator Calvin Ruck told The Canadian Press in 1995. “His actions served to change the view of the ability of Blacks under fire.

“He showed people Blacks could be as good soldiers as anybody else and the majority community didn’t have a monopoly on bravery or devotion to duty. Blacks were just as proud and as loyal to king and country.”

About 100 Blacks saw front-line action on the ground or in the air.

Myth #5: James Munroe Franklin was the first Black North American killed in the First World War.

For more than a century, it has been believed that James Munroe Franklin was the first Black North American killed in action during the First World War.

He served with the Ontario-based 76th and 4th battalions and died four days shy of his 17th birthday, on Oct. 8, 1916, at Regina Trench in the Somme during the Battle of the Ancre Heights.

The Chicago Defender, an African-American newspaper, reported Franklin and his mount were “blown to pieces” by a “huge grandmother shell.”

“Franklin was a self-raised, brave young man and the first Canadian of his Race to die upon the fields of France,” the paper said. “This brave young lad, who gave his life that democracy should rule the wide world over, was the only man of his Race in the whole battalion of 2,000 valiant fighters.”

Franklin may well have been the first Black Canadian killed in the Great War, but Grant says at least two other Black soldiers serving with the CEF, both North Americans, died before Franklin.

U.S.-born Charles Green, a private serving with the 10th Battalion (Canadians), was wounded by gunfire in early 1915, probably at the Second Battle of Ypres in Belgium. He died in hospital on April 26, eight months after the cook and baker from New York City had enlisted at Swift Current, Sask.

Wellesley Seymour Taylor, a Trinidadian-born sergeant in the 14th Battalion (Royal Montreal Regiment), had already been shot twice in the right leg the year before he was killed on May 1, 1916, in the Ypres Salient, likely at a position known as The Bluff, where the 14th suffered nine killed and 37 wounded in seven days on the line. They were relieved the same day the 24-year-old died.

Myth #6: No. 2 collected dead, dug trenches, laid barbed wire, defused landmines and was gassed and shelled.

No. 2 was a labour battalion; fighting and mortuary duties were not among its responsibilities, nor did it suffer any casualties due to enemy fire.

Attached to the Canadian Forestry Corps in France, the battalion harvested and processed vital lumber, built and maintained the roads and railways that transported it to the front, and operated and maintained water systems for the camps. It even ran and maintained electrical systems.

The closest members of No. 2 ever came to fighting was in April 1918 when they trained in infantry skills in case they were needed to help turn back the German spring offensive. They were never summoned.

No. 2 continued providing vital support to logging operations, producing boards for trenches and observation posts and, later, spruce lumber for the French aircraft industry.

Twenty-nine battalion members died during their service, primarily from disease and other illnesses.

Myth #7: No. 2 was last to be supplied and paid, and members were not adequately clothed.

Grant says this misconception may have stemmed from the padre’s diary, in which White noted that a hospitalized soldier was without socks or underwear. There were also supply delays “across the board” after the U.S. entered the war in 1917, she said. “This didn’t just apply to No. 2; it was overall.”

Bottom line: No. 2’s provisions and accommodations were equal to those of other forestry units.

Walker writes that one reason the Canadians were assigned to French territory was to avoid contact with other British “coloured labour” units who were kept in compounds and not permitted the customary liberties afforded white troops.

Black troops in France were completely segregated, forbidden to leave their bases without supervision and barred from cafés and other public places. Blacks who conversed with white women risked arrest, and American authorities beseeched the French military to help keep the races separate.

“Throughout the ranks of the Allies, with the partial exception of the French, non-white soldiers and workers were humiliated, restricted, and exploited,” Walker writes. “It was simply not their war.”

Myth #8: Wartime service liberated Black veterans from prejudice and persecution back home.

Walker said the First World War experience revealed much about what are now called racialized people in Canada.

“Their persistence in volunteering, their insistence upon the ‘right’ to service, their urgent demand to know the reasons for their rejection, all suggest that ‘visible’ Canadians had not been defeated by the racism of white society.”

Many expected their lives would change upon their return to Canada. Their optimism didn’t last.

Some battalion members famously worked as sleeping car porters on the Canadian National and Canadian Pacific railways after the war, fighting for decades for fundamental union rights. Others went on to become lawyers, doctors and engineers.

But despite their wartime service, virtually all of them faced race-related obstacles along the way.

“They came back to the same nonsense, the same racism,” said Grant, co-founder of the Black Canadian Veterans Stories website. Black veterans were even denied membership in veterans’ organizations.

“The Great War, unfortunately, did not end all wars and it certainly did not bring an end to racial prejudice on Canadian soil, notes the Canadian Centre for the Great War, which chronicles the conflict’s social history in Canada. “Canadian blacks were still subjected to segregated housing, segregated employment, and in some instances, segregated graveyards.”

In a 2016 paper on Black enlistment battles and emerging race consciousness in Ontario, historian Melissa N. Shaw said the hardships posed by their enlistment struggles during the First World War “marked a decisive turning point for Black Canadian activism in Ontario.”

Denied what she calls “this fundamental privilege of citizenship”—enlistment—Blacks “pragmatically responded using a variety of political activist methods and strategies to articulate their demands for full inclusion in Canadian society.”

“Much like the Black American approach to later activism,” wrote Shaw, “Black Canadians saw the enlistment battle as an opportunity to ensure their recognition as equal citizens.

“Resilient demands for inclusion came from all angles: from church pulpits to impassionedly penned letters. Black Canadians did not capitulate to Canada’s racial state. Their rejection from the CEF sparked a flame of indignation.”

While the war did not in itself transform prevalent white attitudes toward Blacks in Canada, Shaw said it did prove a “transformative moment” in the race politics that emerged afterward.

“While the battle lines in Europe had been drawn, the racial lines in Canada were less pronounced,” wrote Shaw.

“Informal colour lines were palpable to many Black Canadians marginalized to menial jobs regardless of their skill sets and levels of education. Blacks were often barred from public places such as restaurants, swimming pools, skating rinks, theatres, hotels, and pubs.”

Empowered by their wartime service, many Blacks spoke up for themselves—and their brothers and sisters—and demanded fair treatment.

“In doing so,” wrote Shaw, “they were embarking on what was arguably one of the most arduous and unrelenting battles of the twentieth century.”

Advertisement