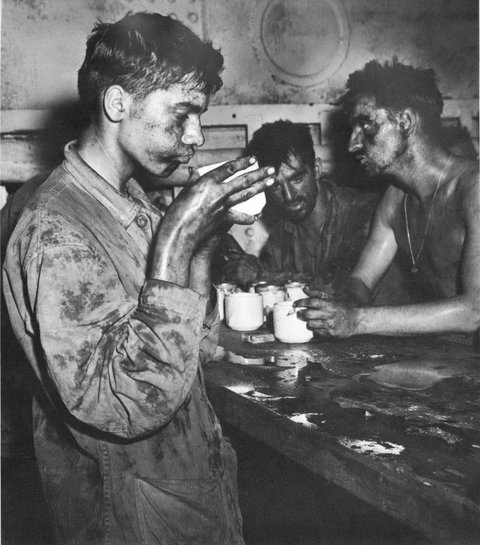

Battle-weary U.S. Marines drink coffee after heavy fighting on Enewetak Atoll in the Pacific Theatre in 1944. [National Archives and Records Administration]

“I would rather suffer with coffee than be senseless.”

– Napoleon Bonaparte

When times are tough and you’re far from home, it’s often the little things that mean the most. You’d be hard-pressed to find a soldier who wouldn’t put coffee near the top of that list.

“Of all the drinks, meals, and other fuels I have experienced in my life as a soldier, it is coffee that stands out as the stand-alone drink of choice and remembrance,” retired U.S. Army colonel Keith Nightingale wrote in Foreign Policy Magazine. “Of all the necessary assets and material, a cup of hot coffee competes with ammunition as a crucial soldier commodity.”

Coffee has been a staple among U.S. military rations since 1832, and a preferred refresher among many a patriotic American since the Boston Tea Party of 1773.

Not so Canada. The British influence remained strong right through the Second World War, when tea was still the drink of choice among Canadian troops who were often subject to British Army rations, supplemented by their own cooks.

The Korean War marked a turning point for the Canadians, who started out the peninsular “police action” on British rations—including tea—but came to prefer the more palatable American foodstuffs, which inevitably entailed coffee.

For the soldier in the field, the sailor on watch, or the aircrew operating on little sleep, coffee has become not only a refresher and an alertness aid but, as with the public at large, it’s evolved into a social fulcrum around which conversations turn and good times—brief but memorable—roll.

In war, those who fight while living in dugouts, foxholes and trenches, in cramped quarters aboard ships at sea, or in tents at dusty, far-flung air bases all come to cherish the moments of respite when the coffee’s hot and the talk is high.

“The secret to the United States military won’t be found locked inside a room at the Pentagon nor encrypted on a secure network behind a firewall,” Neil Fotre wrote for The Military Times in 2018. “It’s found in mugs on messy workstations, in the hands of a sailor half-asleep just off of watch and brewed in chow halls all over the globe. It’s coffee.”

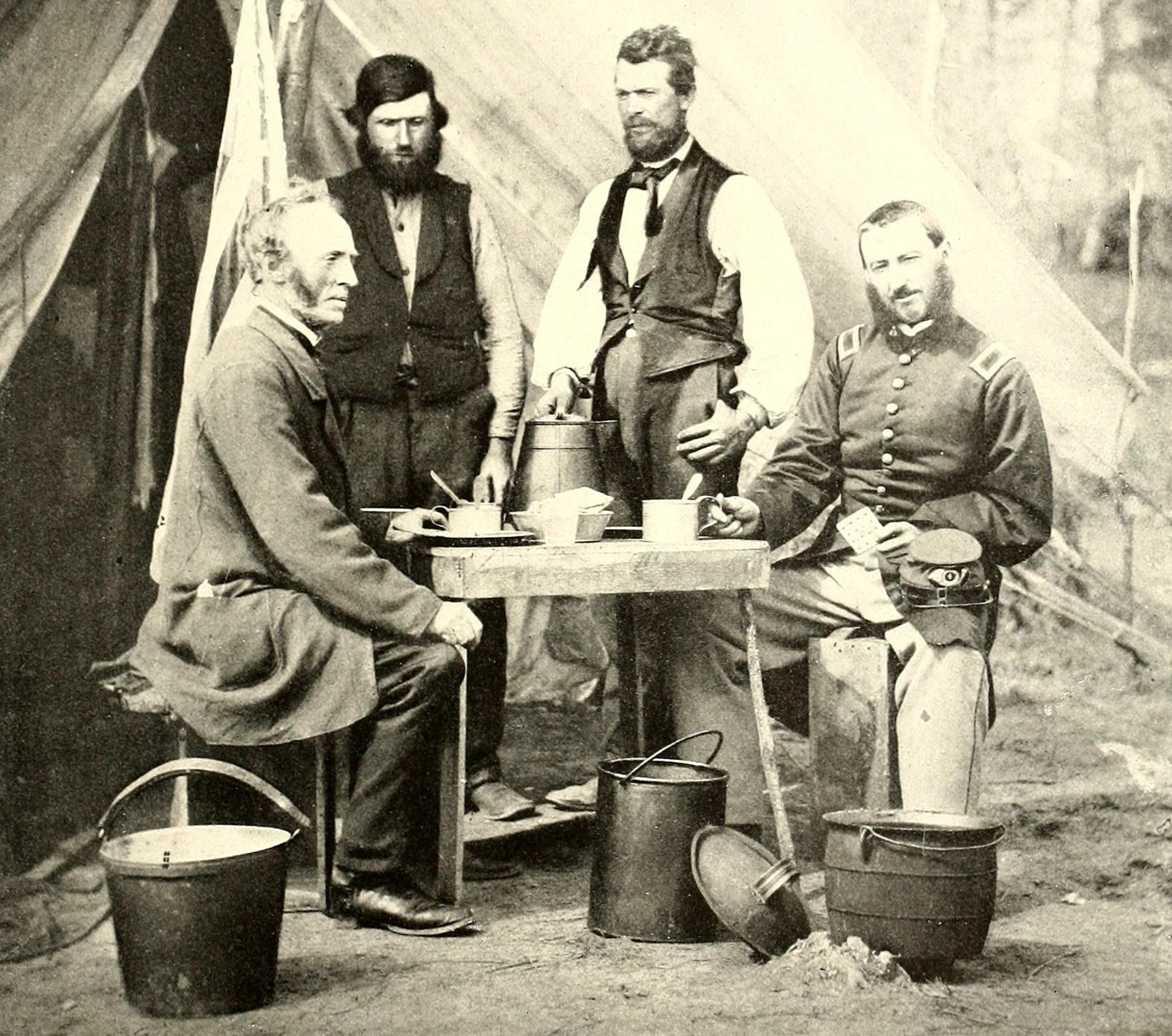

Soldiers with the Union Army drink coffee from tin cups and eat hard-tack biscuits during the American Civil War. [Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection/Flickr The Commons]

“Everything is chaos here,” Gilpin recorded. “The suspense is almost unbearable. We are reduced to quarter rations and no coffee. And nobody can soldier without coffee.”

In fact, instant coffee was a product of the Civil War—a long-lasting, efficient means of fuelling the troops, minus the need for brewing equipment.

Coffee was already in such demand at the time that the Sharps Rifle Company began manufacturing a carbine in 1859 with a hand-cranked grinder built into its butt stock. Union soldiers would fill the stock with beans, grind them up, dump them out and use the grounds to cook the coffee.

Come morning, Union camps would be abuzz with the sounds of thousands of grinders simultaneously crushing beans that, ironically, were the product of Brazilian slave labourers not unlike those for whose freedom they were fighting.

Jon Grinspan, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, was looking for “big stories” when he began digging through war journals in the nation’s Civil War archives.

Instead, “all they kept talking about was the coffee they had for breakfast, or the coffee they wanted to have for breakfast,” Grinspan told U.S. National Public Radio in 2016. The word ‘coffee’ was more present in the diaries than the words ‘war,’ ‘bullet,’ ‘cannon,’ ‘slavery,’ ‘mother,’ or even ‘Lincoln.’

“You can only ignore what they’re talking about for so long before you realize that’s the story,” Grinspan said.

Union soldiers were issued 36 pounds of coffee a year, and they made their daily brew with water from canteens and puddles, brackish bays and Mississippi mud—fluids their horses wouldn’t even drink.

“Soldiers would drink it before marches, after marches, on patrol, during combat.”

Confederate troops weren’t so lucky. Union blockades cut off access to coffee in the South. Desperate Confederate soldiers resorted to makeshift coffees, roasting rye, rice, sweet potatoes or beets until they were dark, chocolatey and caramelized. The brews contained no caffeine, but they were warm, brownish and somehow comforting.

Canadian soldiers recharge at a soup kitchen near the front line during the Battle of Hill 70 in August 1917. [LAC—PA001596]

Coffee filled the void and, while its origins are disputed, old salts say that displeased sailors referred to the replacement as a “cup of Joseph” in a grudging nod to Josephus Daniels. The phrase was later abbreviated to “cuppa Joe.”

During the 1930s, the Nestlé company developed its Nescafé brand in conjunction with Brazilian industry moguls, who had vast quantities of stockpiled coffee ripe for the market. Nestlé had developed a spray-drying technology that it was using to powder milk and this same technique was used to powder coffee beans.

American servicemen enjoy cups of coffee at a Salvation Army hut in New York, circa 1918. [FPG/Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

In his story for FP, Nightingale imparts coffee memories from across a long and eventful military career. During North Vietnam’s Tet Offensive of 1968, he recalls the grinding urban warfare that took place in the South Vietnamese city of Hué, where opposing forces were as close as 15 metres apart throughout one of the longest and bloodiest battles of the Vietnam War.

He describes how day and night merged, exhaustion became a state of euphoria, and wakefulness was a constant requirement.

“We are all catatonic, but artillery must be adjusted, airstrikes guided, and mortal decisions made regarding the next door to assault,” he wrote.

“My bodyguard, a Montagnard, makes a small fire out of splintered ammo boxes on our rooftop overwatch position. He heats water in an aluminum teapot which he always has on his rucksack. He pours the boiling water into an aluminum fixture over a cup filled with impossibly fine, highly roasted coffee grounds.

“He adds a large spoonful of sweetened condensed milk, swirls the mix with a stick and offers it to me. I take it down, first slowly and then in haste. I close my eyes and enjoy the flavors and the moment. Back to work.”

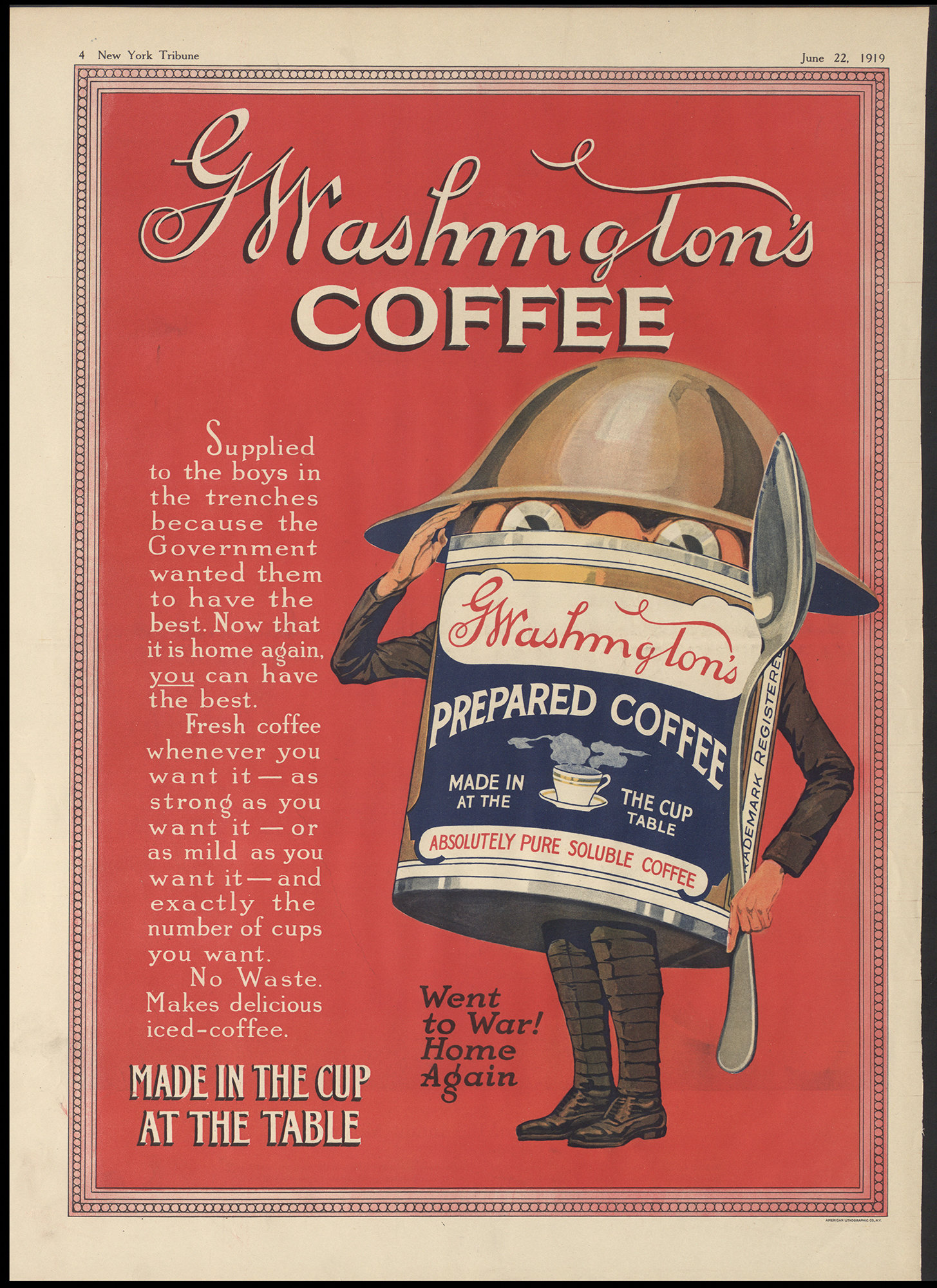

An ad in the New York Tribune on June 22, 1919, promoted “Washington’s Prepared Coffee,” a type of instant coffee that had been part of soldiers’ rations in the First World War. [New York Tribune/Library of Congress]

“As the anti-war movement heated up,” NPR reported, “these coffeehouses became places where G.I.s could get legal counseling on issues like going AWOL and obtaining conscientious objector status, and learn about ways to protest the war.

“Many coffeehouses also began publishing newspapers, with exposés on poor conditions within military prisons, op-eds from disillusioned soldiers and information about rallies and demonstrations.”

Their profile became such that then-president Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration began monitoring them for “subversive activities.” In August 1968, the U.S. Army chief of staff, General William Westmoreland, sent LBJ a secret memo: “Consensus is that coffeehouses are not yet effectively interfering with significant military interests, and, consequently, suppressive action may be counter-productive.”

Today, coffee shops offering all manner of designer coffees are on practically every city corner. Coffee is an integral part of the social and cultural fabric of North American life—especially, it turns out, in Canada.

Per capita, Canadians drank 6.5 kilograms of coffee in 2019, according to the online journal Coffee Business Intelligence. That’s the 10th highest rate in the world, well ahead of either the United States (26th) or Great Britain (45th). The average Canadian coffee drinker consumed 3.2 cups a day, and they can be very particular about what they drink.

In March 2002, the commander of Canadian operations in Afghanistan, then-lieutenant-colonel Pat Stogran, was cooking up some breakfast at the end of a major combat assault. Supplies were low after an exhausting five days humping around the mountains of eastern Afghanistan, and so was the morning sun. Taliban and al-Qaeda fighters were still suspected to be in the area.

Nevertheless, Stogran produced a tea, handed it to a corporal, and dispatched him a few metres across the campsite to present the drink to a television news producer who, along with her crew, had come late to the party a few days before. She rejected the gift, declaring that she didn’t drink tea, she wanted coffee.

The somewhat sheepish grunt returned, handed the colonel the full cup of tea and delivered the bad news. Stogran barely batted an eye, ditched the contents, and set about making her his last batch of coffee—black, because that’s all he had. He sent the same soldier back on another delivery run.

The producer took the cup, looked inside and declared, her voice dripping with disappointment: “Oh, I wanted a double-double.”

Stogran had his cuppa Joe, after all.

Advertisement