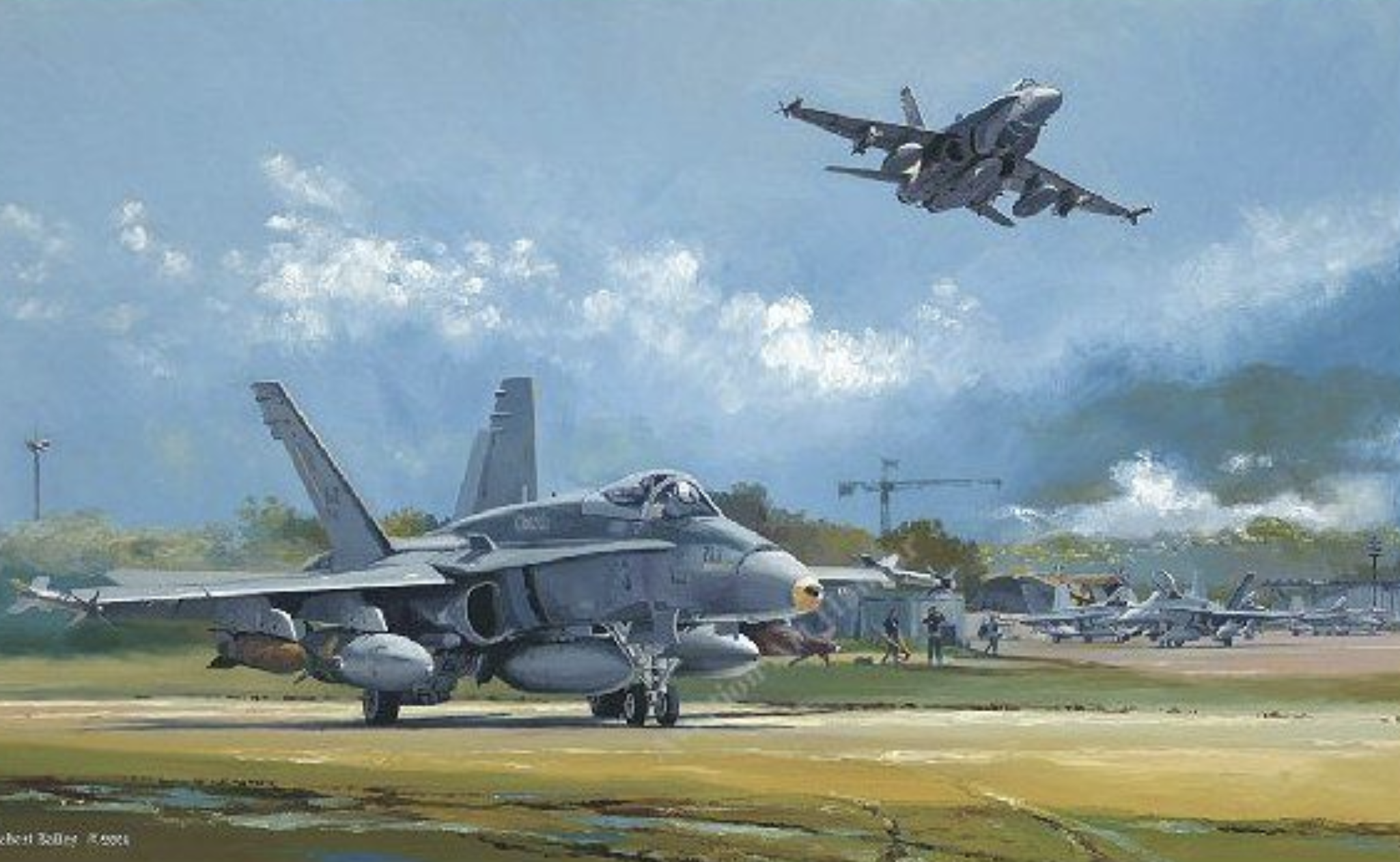

Canadian CF-18 Hornets take off from their base in Italy to strike targets in Kosovo in 1999, depicted in the painting “Balkan Strikers” by Robert Bailey. [Robert Bailey]

In 1989, Serbian president Slobodan Milošević repealed constitutional autonomy of the province of Kosovo; Kosovo’s ethnic Albanians, who had long suffered persecution by Serbs, began protests that grew increasingly violent throughout the civil war marking the breakup of Yugoslavia.

The situation grew steadily worse after Milošević assumed presidency in 1992 of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, a union of Serbia and Montenegro. The Kosovo Liberation Army rebelled against the Serbian establishment in Kosovo. Milošević responded with a brutal campaign of retribution, including genocide, which was referred to as ‘ethnic cleansing.’

In 1998, it was feared the civil war would result in a Nazi-like “final solution” for ethnic Albanians who made up 80 per cent of Kosovo’s population. Nearly 1.5 million Kosovars were expelled from their homes and more than 13,000 people were killed or went missing.

NATO intervened, launching a “humanitarian” war. When diplomacy failed, it sent in bombers, and warned the bombing would not stop until Milošević agreed to end the violence and allow safe return of refugees.

Four CF-18 Hornets were among 16 bombers that left an airbase in Italy on March 24, 1999, headed for the first bombing mission in Kosovo. Of the four, two hit their targets with 500-pound laser-guided bombs, one missed and one did not release bombs because the target had not been identified to the pilot’s satisfaction.

Over the next 78 days, 18 Canadian CF-18s flew 678 combat sorties, dropping 532 bombs on targets in Kosovo and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. It was the RCAF’s most intense combat operation since the Second World War and it stretched the air service to the limit. Pilots were either airborne or preparing to fly, it was reported in the first edition of the Canadian Military Journal in 2000.

Milošević accepted the agreement proposed from diplomatic negotiations, and the bombing stopped June 10.

At a press conference at the end of the campaign, it was pointed out that though a distinct minority, Canadian pilots were asked to lead more than half the missions in which they took part and Canadian crews hit their targets 75 per cent of the time.

The bombing campaign was controversial, for bombs, despite lasers and other guidance systems, can be indiscriminate, destroying military targets and nearby civilians and their property. NATO estimated no more than 30 such instances, but Human Rights Watch verified 500 civilians were unintentionally killed in incidents like those in which bombs and shrapnel hit apartment blocks and homes, a passenger train, and a group of children in a village. NATO responded that it does not target civilians “but we cannot exclude harm to civilians or to civilian property during our air operations over Yugoslavia.”

Canadian pilots were under instructions not to drop the bombs if uncertain about the target or concerned about collateral damage. “This aspect of aerial warfare is one of the new challenges for today’s modern warriors,” says the Journal.

Over the following two decades more than 600 Kosovars have been killed by unexploded bombs, buried mines and grenades. More than 40,000 such devices have been removed since 1999, and the Halo Trust, which clears landmines and explosives in communities following conflicts, expects the country to be free of unexploded ordnance by 2024.

DOWNLOAD NOW

Advertisement