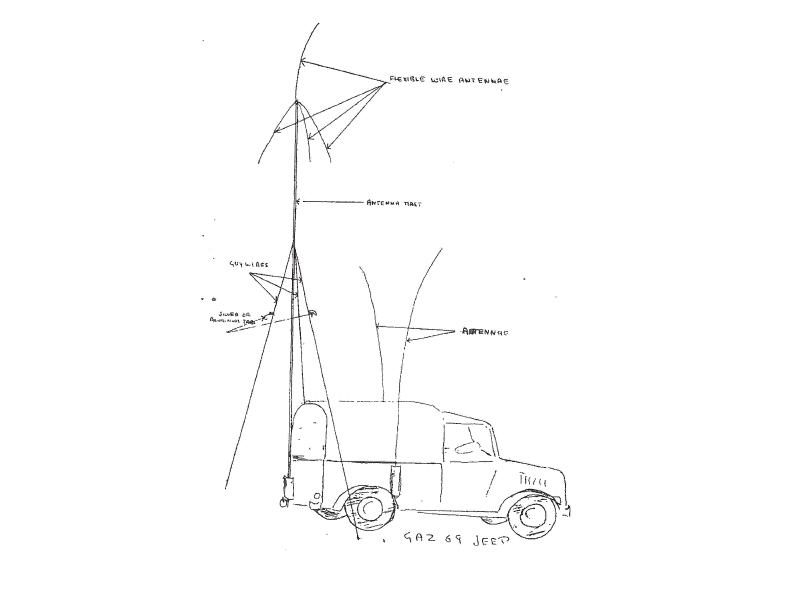

The story of a young Canadian diplomat spying on the Soviets in Cuba on behalf of the CIA with the blessing of our prime minister is improbable, but no more so than its context. This was the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, when the world came within a hair’s breadth of a nuclear holocaust.

The context extends to the immediate and still-perilous aftermath of that drama in which my miniscule role was played. Incidental to the story, but relevant to present-day missile rattling, is the memory of how hubris and stupidity almost brought the planet to its worst modern disaster and how, in the end, strength of character and human values on the part of the two foremost protagonists reeled the world back from the edge of the precipice. The protagonists were, of course, Nikita Khrushchev and John F. Kennedy.

The genesis of the missile crisis lay in the East/West polarization that emerged from the Second World War. There were other factors, not least of which was the Cuban Revolution. But two other events help to explain why Khrushchev gambled that his bold plan to install missiles in Cuba would succeed without provoking a nuclear war—thereby conferring upon the Soviet Union a major strategic advantage.

Observer: Cuban president Fidel Castro, author John Graham and Léon Mayrand, Canada’s ambassador to Cuba from 1963 to 1970. [Courtesy of John W. Graham]

The first event was the Bay of Pigs Invasion. Shortly after dawn on Monday, April 17, 1961, a ragtag paramilitary force of more than 1,400 Cuban émigrés struggled ashore at a swamp-encircled inlet on Cuba’s south coast. The inlet was the Bay of Pigs. The invasion was an unbroken chain of disasters and its swift defeat became the most humiliating debacle of Kennedy’s extraordinary presidency.

Kennedy had inherited a plan that had the blessing of President Dwight D. Eisenhower and had been conceived in the last months of that administration. Eisenhower and many others in Washington saw in Fidel Castro’s blossoming relationship with Moscow the spectre of Soviet mischief and influence spreading into Latin America, long regarded as America’s backyard. The invasion of Cuba by Miami-based exiles was expected to ignite widespread opposition within the island and lead to the overthrow of Castro.

Funded, trained and armed by the CIA, the operation was placed under the command of CIA officer Richard M. Bissell Jr. If the operation was almost doomed from the outset because it was based on flawed intelligence (especially the belief that a majority of the population would support an armed revolt against Castro), then it was unquestionably doomed by the choice of Bissell. A well-connected Ivy League patrician, Bissell had schmoozed his path up the CIA ladder to become the head of clandestine activities, an area where his only notable success was an American role in the assassination of the Dominican dictator, Generalissimo Rafael Trujillo. (Bissell’s agents had smuggled weapons to the conspirators in frozen meat carcasses, via an acquaintance of mine in Santo Domingo nicknamed Wimpy.) Many of his other activities were focused on bizarre plots to kill Castro, including exploding cigars.

Until the Bay of Pigs, Bissell’s most notorious disaster was the failure to warn pilot Gary Powers that his U-2 spy aircraft overflying the Soviet Union was within range of a new generation of Soviet surface-to-air missiles. The downing of the U-2 and Powers’ capture was a major embarrassment, costing the United States both treasure and face. Bissell was reprimanded but survived.

The Bay of Pigs catastrophe was on a grander scale, entrenching the Castro regime and playing into the hands of the Soviet Union. Some blame was attached to Kennedy. As he saw disaster looming, the president attempted to reduce the blatant visibility of U.S. involvement by cutting the CIA airstrike by half. But this time Bissell’s luck ran out. The culprit, whose smooth talk had assured the White House of success, was summoned to the Oval Office, where the president remarked: “In a parliamentary government, I’d have to resign, but in this government, I can’t.” Bissell was through.

For Kennedy, damage control was only beginning. There was outrage in the country and he could not leave some 1,200 prisoners, whose fate was ultimately his responsibility, to rot in Cuban prisons. A hefty and mortifying ransom in food supplies and medicines was paid for their release. Worse, America’s timid conduct during the invasion appears to have sown a seed in Khrushchev’s mind that a hapless Kennedy could be outflanked in the Cold War.

Summit President John F. Kennedy of the United States greets Premier Nikita Khrushchev of the Soviet Union in Vienna, Austria, in June 1961. [Alamy/E0W3X1]

The second event was the summit between Khrushchev and Kennedy two months later in Vienna, where they met for the first time to grapple with crises in Berlin and Laos. At the end of the meeting, Kennedy confided to a friend that he had been “savaged” and that his poor performance might provoke Khrushchev into a miscalculation that could lead to nuclear war. This intuition was almost proven right.

Tensions had been building, even in Canada. In Carp, Ont., 30 kilometres west of Ottawa, the Diefenbunker was hollowed out of the ground to accommodate key members of government in case of a nuclear strike. Across the country, property owners were building bomb shelters in their basements and backyards.

The feeling of madness in the air, the pressure to break the few threads that anchored sanity to the ground, is captured in Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 film Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, a fantastic black satire on how easily the United States and the Soviet Union could slip into nuclear war. It features “stupidity and hubris” and was nominated for four Academy Awards, including best picture.

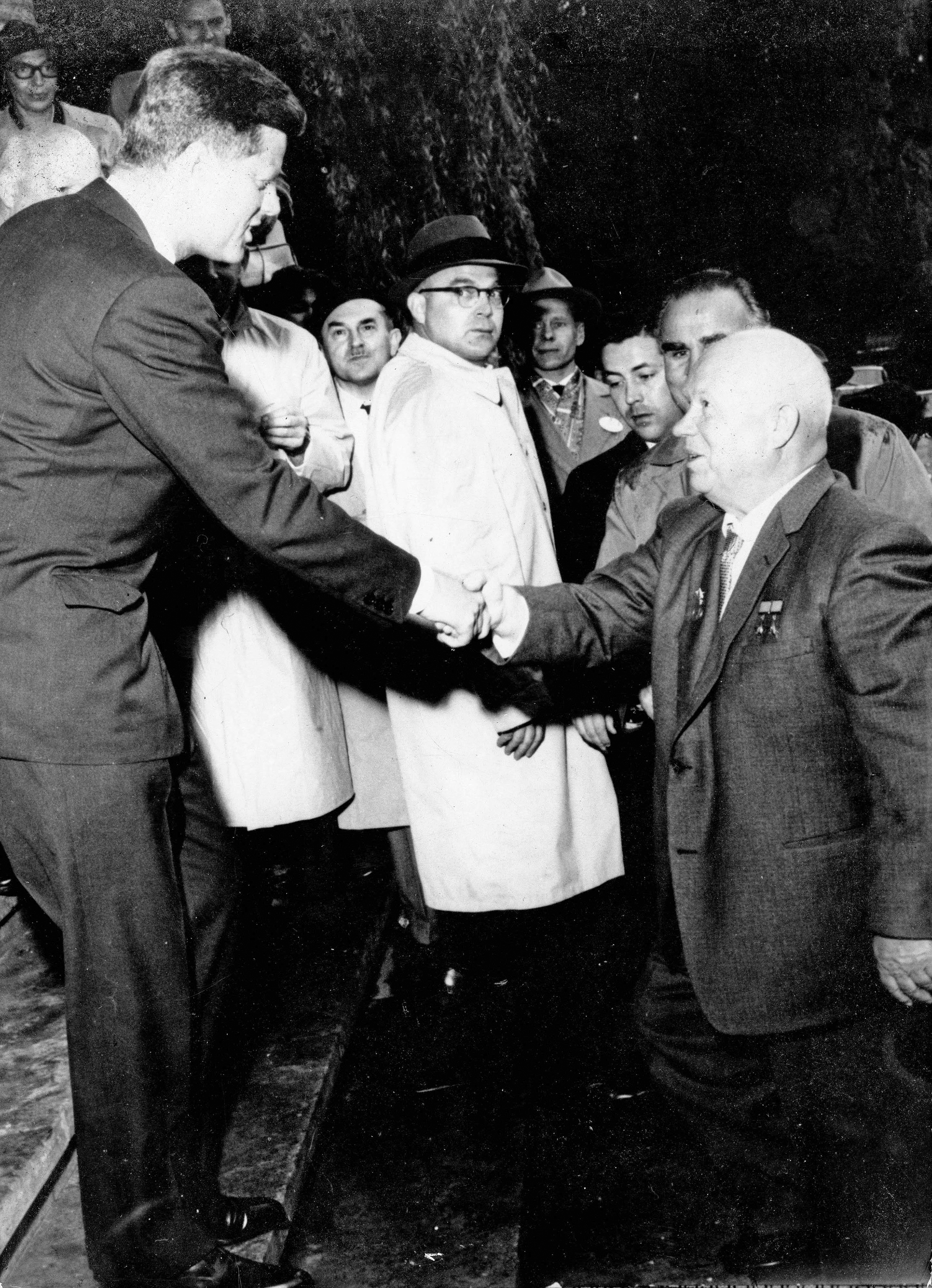

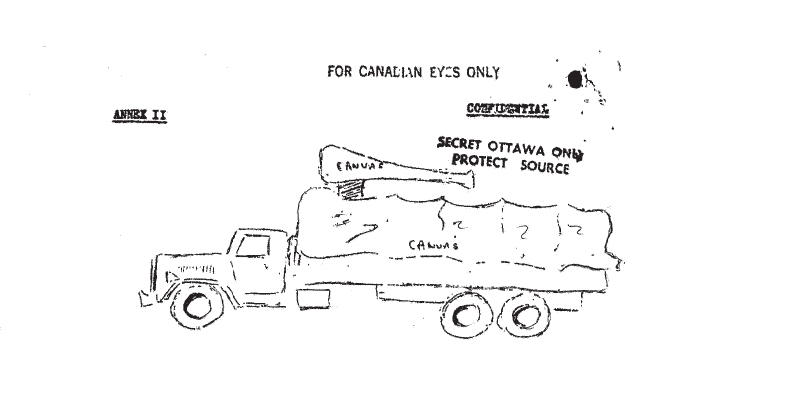

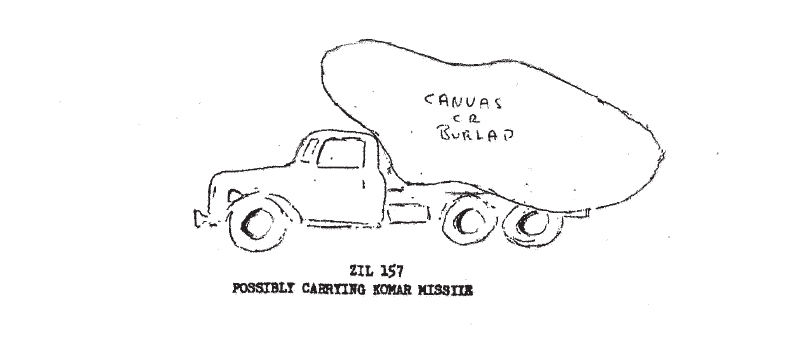

Declassified drawings

Several of my sketches are still marked with extravagant security classifications, but they are now declassified. Canada’s Department of National Defence has since declassified many of the documents related to my activities in Cuba, but the key bit—which revealed the link between the Canadian government and the U.S. government and CIA—was found by Don Munton of the University of Northern British Columbia, an academic friend who discovered several of my telegrams (addressed to Ottawa) in the Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston. The telegrams had been declassified and formed part of packages of selected documents sent periodically to the White House by the CIA. (Photos courtesy of John W. Graham)

Khrushchev began to secretly ship intermediate-range missiles and nuclear warheads to Cuba. In mid-October 1962, American reconnaissance aircraft detected several of these ships, the presence of missiles and the installation of launch sites in Cuba.

On Oct. 22, Kennedy issued an ultimatum that all Soviet ships carrying missiles and missile components to Cuba must return to port. He also declared DEFCON 3

for the U.S. Armed Forces—a defence-readiness condition in which the air force is ready to mobilize in 15 minutes. Two days later, he raised it to DEFCON 2, the nation’s second highest military alert—one level short of war.

These were the tensest 13 days in modern history. The U.S. asked NATO allies to collaborate. They obliged—the only major exception was Canada. Apparently because he disliked and distrusted the young American president, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker stalled for two days. In defiance of the prime minister, defence minister Douglas Harkness ensured that service co-operation did take place. However, the damage was done. U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy remarked: “Canada provides all aid short of help.”

As the crisis grew, hawks, both military and civilian, in Moscow and Washington pressed their respective superiors to pull the trigger, arguing that the only winner would be the side that launched a pre-emptive nuclear strike. Fortunately, they had misjudged their leaders. It is difficult to imagine two more different men: Khrushchev, son of peasants, veteran (as a commissar) of both world wars, including the Battle of Stalingrad (one of the most gruelling and decisive battles of the Second World War) was the brightest and most brazen of Russia’s Cold War leaders. Tough, often ruthless, he successfully struggled up one of the world’s most slippery and dangerous ladders to take control of the Kremlin in 1958. Kennedy, a wealthy Harvard playboy with a heroic Second World War record in the South Pacific, became president in 1961.

Yet there are clues. Khrushchev broke with the grim Stalinist legacy and introduced some liberal reforms. As leaders, neither were intimidated by pugnacious colleagues and as the missile crisis unfolded both understood the stakes and stood down their respective hawks.

The best example was the message dictated by Khrushchev on Oct. 28 in response to a message from Washington. Khrushchev said that he would withdraw his missiles in exchange for an American promise not to invade Cuba—a decision that some of his generals described as humiliating and that Castro denounced as a “betrayal.” Amid the growing risk of events slipping out of control, and knowing that to encrypt the message in Moscow, decrypt it in Washington and deliver it to the White House might take 10 hours, Khrushchev ordered the message sent en clair over Radio Moscow. The crisis was over. Soon after, both leaders described the nightmare they had lived through as “insane.”

But was it over? Mostly, but not quite. Aerial reconnaissance had given Kennedy’s people reasonable confidence that Khrushchev had withdrawn the nuclear weapons. However, the level of trust was understandably low. Acknowledging this American anxiety, Khrushchev agreed to United Nations on-site verification, but Castro vetoed the arrangement, calling it an “abuse of Cuban sovereignty.” This was a major concern.

Meanwhile, more anxiety issues emerged. Aerial photography revealed the presence of mobile nuclear weapons. NATO called these Soviet short-range artillery rocket systems FROGs (Free Rocket Over Ground). They had a range of about 80 kilometres and could be tipped with small nuclear warheads. Their withdrawal was not part of the agreement. The existence of surface-to-air missiles (SAM), Komar-class guided-missile speedboats, and the continued presence of thousands of Soviet troops intensified the need for more ground-level intelligence.

The CIA had a network of agents in Cuba, but most were rolled up by an increasingly professional Cuban counter-intelligence force. They clearly needed more help—and urgently—otherwise it is unlikely that they would have sought eyes-on-the-ground covert intelligence help from an ally which did not even have a professional foreign intelligence service.

This is where the amateur—me—enters the picture. The U.S. government specifically asked if Canada would send an officer to our embassy in Havana who the CIA could task with monitoring Soviet military movements and sites as well as Soviet and Eastern European merchant shipping to and from the island.

Why me? I was concluding my first posting at our embassy in the Dominican Republic and I had Spanish. I was also a reserve officer in the Royal Canadian Navy, but I don’t think that was a factor. The potential hazards were not discussed. Perhaps they thought I was expendable.

My briefing in Ottawa was short, since there was not a lot they could tell me. The most useful advice came from my colleague George Cowley, who had been rushed to Havana to start the intelligence work pending my arrival from Santo Domingo. Returning to Ottawa, he shared with me his newly acquired trade secrets. We spent an afternoon at Zellers, where Cowley picked out attire resembling that worn by Soviet soldiers in Cuba: khaki trousers, plaid shirts and tennis shoes. Moscow claimed that all troops had been withdrawn, leaving only a few attachés at the embassy. This was a stretch. In 1963, their numbers were 30,000 to 35,000. If anyone asked, they were “agricultural experts.” The Russians in Cuba actually described this clandestine enterprise as “Operation Checkered Shirt.” Cowley advised that I needed camouflage. With my new wardrobe, I was almost ready for Cuba.

The next steps were visits to Washington, D.C., then CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia. These briefings were intense and practical. At the end, I was thanked for taking on the assignment and then presented with a gift—a small, sophisticated camera with telescopic lenses. I should have anticipated the “gift” and my mind raced—about what would happen if I was stopped with incriminating film by the Soviets or Cubans. It seemed to me that any alert security patrol would want to investigate a stranger, even in a look-alike Russian plaid shirt, lurking around military installations. If caught, there would be repercussions. After a few moments, I politely declined.

“But how will you give us the details we need about guidance and other electronic equipment? Precise configuration is necessary for recognition,” said a baffled American.

“I sketch,” I said. “I will send sketches.”

Dismayed, my new CIA friends were no doubt thinking black thoughts about secret agents in Havana producing drawings of the inner workings of vacuum cleaners to bamboozle their employers, as in Graham Greene’s classic spy novel Our Man in Havana. But sketching is what I did.

Launch site: A U.S. State Department official in Washington points to a suspected missile launch site on an aerial reconnaissance photo taken near San Cristóbal, Cuba, west of Havana, in October 1962. [Alamy/hpdk64]

On the ground in Havana, I was accommodated in an attractive bungalow in what had been the upper-bourgeois suburb of Cubanacan. It came fully furnished plus Pura, a splendid maid, and Blackie, a large dog of mixed breeding. The owner, an American who owned a small factory, was leaving and had offered the residence to his friend, the Canadian ambassador, to use as he saw fit. The owner expected to return in a few months, as soon as the “unpleasantness” with Fidel Castro came to an end.

I was based at the Canadian Embassy on Quinta Avenida, but much of my time was spent in the country—often on poorly identified back roads. The job was to identify Soviet weapons, electronic detection and communications systems, and the movement of Soviet troops and equipment by road and in ports. American reconnaissance by high-flying U-2s, RF-101 Voodoos and RF-8 Crusaders provided the locations and rough configurations of Soviet military installations, but not enough detail. With this information plotted on a map, I would set off in my Volkswagen Beetle, almost invariably on back roads, and drive as close as I could to a site perimeter—not too close, but close enough to sketch and take notes. Sometimes the camp was too well hidden or the approach road led only to the camp gate, alerting even the most gullible of Soviet guards to my intentions. One time, when a colleague, former sergeant Vaughan Johnstone, and I felt too exposed, we pretended to change a non-flat tire.

Back at the embassy I would attempt to identify the equipment by referring to a NATO manual. My sketches depicted SAM, Cruise and Komar missiles and much else. I did not spot a FROG. My findings were dispatched by diplomatic bag to Ottawa or, in the case of something significant, by telegram using a specially dedicated cipher machine.

SAM sites were important, especially since Oct. 27, 1962, when a Soviet anti-aircraft weapon fired two missiles, bringing down a U-2 overflying Cuba and killing the pilot, U.S. Air Force Major Rudolf Anderson Jr., and almost triggering a massive U.S. reprisal.

One long night sticks vividly in mind. Air reconnaissance reported that a SAM base was packing up, either for redeployment within Cuba or for shipment back to Russia. The Soviet army moved its installations by night to avoid overhead detection. I was given the base co-ordinates and asked to scout the area—a two-hour drive from Havana. Just before midnight, I was driving along a secondary road when I saw the dimmed lights of a line of trucks approaching. A long convoy of vehicles, including articulated trucks, with long canister-shaped loads sheathed in canvas, was moving eastward—all recognizably Soviet vehicles. Bingo! I had my quarry. But zipping past it left insufficient time to take notes. I paused in the shelter of trees by the side of the road, reversed my Beetle and then leapfrogged two or three vehicles at a time with my pen busy in my right hand. No one stopped me, no motorcycle pursued me. Why not?

Another similar event was an expedition to Punta Brava, a town a few miles southwest of Havana, to search for a SAM base. Several bases were being relocated to the Havana periphery, apparently to provide the city with an improved defensive umbrella.

Approaching a gas station on the Carretera Central, I spotted a tertiary road bearing the tire marks of heavy trucks. I followed the road through cane fields for about half a mile where it was blocked by a single swing pole in front of what was obviously a Soviet camp. My approach—or maybe the grinding of my Beetle’s gears—disturbed a solitary, unarmed and slumbering guard, dressed in the same checkered-shirt uniform I was wearing. He was peering at me as I took a quick scan of the scene, and reversed in a cloud of dust.

Back on the highway and with no visible sign of anyone haring after me, I stopped and drew three rough sketches—trying to recall the overall layout, the distinctive shape and configuration of radar antennas poking above camouflage canvas, and details of a long, covered canister-like object on a trailer. This was probably a SAM, and by grim coincidence, my sighting occurred exactly one year after Major Anderson’s U-2 had been destroyed by SAMs. Again, no one came looking for me.

Years later, more questions were raised about these adventures. Why wasn’t I caught?

There are several possible explanations: (1) the Russians thought I was one of them with my Zeller’s disguise and brown hair; (2) the Russians didn’t speak Spanish and could not interrogate me; (3) the Russians didn’t trust Cuban security, which was more likely to have spotted me as a fake; (4) the Russians may have welcomed an “inspection” to prove that the missiles and warheads had gone (since Castro had vetoed the agreement to allow a UN inspection; and (5) luck.

Was Canada right in accepting the U.S. request to supply a spy? To my mind, absolutely. And not simply to remove the bad taste of Diefenbaker’s initial hesitation or to collect brownie points from our closest ally. Whatever dark places the CIA had been and would go, this operation made sense.

Was it useful? Did my work do any good? Nothing spectacular, certainly. But regular, systematic reporting did help erase a multitude of question marks on maps in Washington and Langley.

In some cases, it was a matter of demystifying a site considered by the CIA to be potentially sinister. For example, Langley was puzzled by a formation of concentric concrete tubs. I identified them as cattle troughs. Small beer, I know, but this process helped step by step to build confidence that Khrushchev and his armed forces were respecting their commitment under the agreement and to increase the distance between fingers and triggers.

John W. Graham’s memoir Whose Man in Havana? Adventures from the Far Side of Diplomacy (University of Calgary Press) contains a more detailed account of Cuba in the 1960s and other exotic and troubled waterfronts.

Advertisement