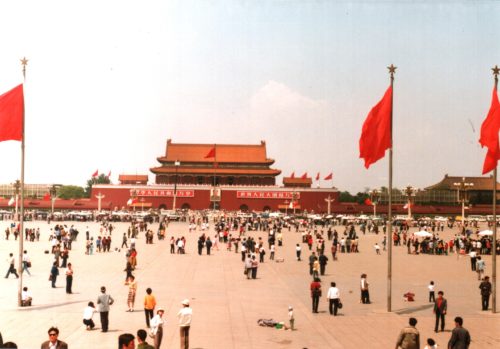

Tiananmen Square 1988. [Wikimedia]

That idealism, however, was not just gone after the Tiananmen Square protests, it was trampled, shot and wiped clean by martial law in the public space in China’s capital. It was an effective end to any hope for greater freedoms in the country and, to some, a better future. And as Asian communities throughout Canada commemorate the 34th anniversary this month of the infamous protests and massacre, they also stopped to remember the day that also impacted Canada’s cultural makeup.

In the spring of 1989, things were changing quickly in China. A progressive group of students, scientists and intellectuals were looking to enact change to the country’s political, social and economic structure. How? By challenging the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

“It started out with such excitement,” Diana Lary, then the Canadian embassy’s in-resident sinologist, told CBC. “We thought that something terrific might be happening in China.”

A risky enterprise at the time, China’s government had sought to encourage select groups toward greater participation in central politics, little anticipating the snowball effect it would have.

Throughout the 1980s, the CCP had opened its borders to private companies and foreign investment, sparking economic growth, liberalization and, of course, more corruption. Chinese students, now exposed to western customs, wanted higher standards of living.

It wasn’t just college campuses where these ideas were being discussed. CCP general secretary Hu Yaobang was in favour of the public’s call for greater democratic freedoms and less corruption. This, however, later worked to Hu’s detriment when he was forced to resign in 1987 by the CCP’s more conservative majority. Still, Hu didn’t give in, leading fellow supporters on a hunger strike.

A Type 63 armored tank deployed by the People’s Liberation Army in Beijing during the 1989 protests.

Some 7,000 people were injured, but the total number killed is unknown.

But it was only after Hu suffered a fatal heart attack on April 15, 1989, that protests broke out across the country. Rallies in support of change were held in Shanghai, Nanjing, Xi’an and others.

The demonstrators were hopeful that the issue could be resolved peacefully, particularly since the government was issuing nothing more than stern warnings against the protesters. But that would all change in mid-May when Soviet President Mikhael Gorbachev visited, accompanied by throngs of Western journalists.

“No one in the leadership knew what to do about it,” said Lary.

With premier Li Peng and elder statesman Deng Xiaoping worried as much about anarchy as they were about a tarnished international image, they declared martial law in Beijing. The Chinese army, however, soon found that its attempt to disperse crowds was futile, with thousands of Beijing citizens blocking them.

It would take brute force on the night of June 3-4 to get past the protesters, with the sounds of AK-47s ringing through the streets. Buses ablaze, tanks rolling past, the wounded in pull-carts. The chaos was untenable. Some 7,000 people were injured, but the total number killed is unknown.

“It came to an ugly, sorrowful end,” wrote journalist Bob Mackin.

A replica of Goddess of Democracy outside of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. [Wikimedia]

But change didn’t only happen in China; it occurred in Canada as well.

The effects of the Tiananmen Square massacre were far-reaching, leading to a distinct shift toward the strict, conservative culture in China today.

“[Tiananmen] led to the rise of conservative leaders like Li Peng,” wrote Tiberghien. “It led to a freeze on political reforms for many years.”

But change didn’t only happen in China; it occurred in Canada as well.

Just one year later, Chinese and Hong Kong immigration to Vancouver doubled. And in 1994 alone, the city welcomed 43,000 immigrants from the region.

With such an influx, Vancouver itself changed.

The new demographic of largely professional and educated people, boosted development and the real estate market in the city. Similarly, there was growth in the number of private schools and university spaces, along with a much more diverse Asian cultural scene.

Naturally, Vancouver now welcomes some of Canada’s largest Tiananmen Square vigil services, with this year’s gathering attracting more than 1,000 people to David Lam Park.

Though the Tiananmen Square massacre remains a horrific memory for many Chinese Canadians, Lary noted he is still optimistic about China’s future. “China’s history is long and full of examples where injustices…have been rectified.”

Advertisement