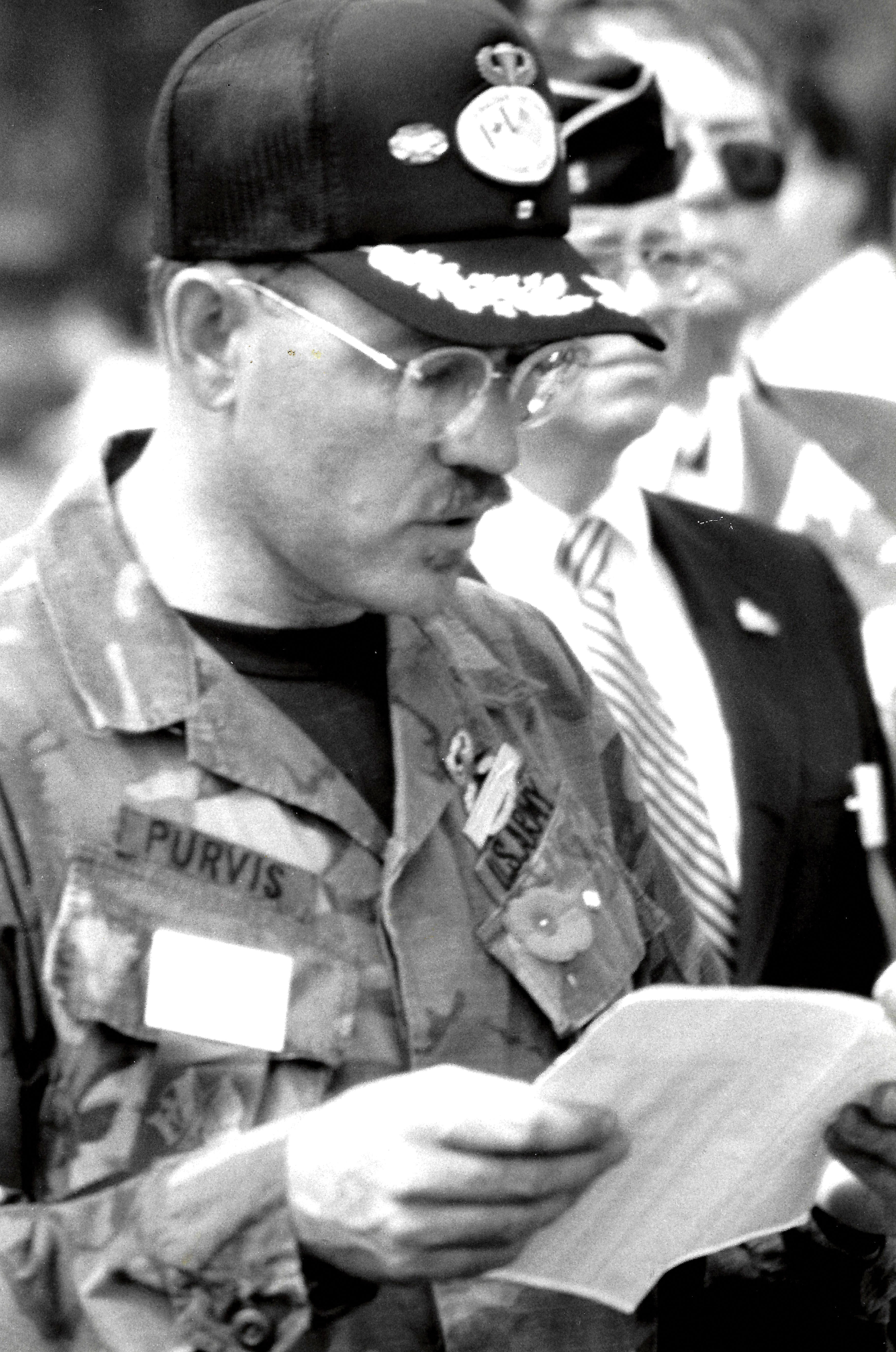

Rob Purvis (right) with other members of the U.S. Army’s K Company, 75th Infantry Regiment (Ranger) in the An Khê District of Vietnam in 1970. [Courtesy of Rob Purvis]

Rob Purvis was 20 years old when he, Butch, Larry and Billy—school buddies from Winnipeg—crossed the border and joined the United States Army in Fargo, N.D. It was 1968, they needed work and they yearned for adventure. They got work, all right, and more adventure than they had bargained for. They all wanted to go to Vietnam, and they all did.

Larry Collins, 22, would die there. Purvis and the others would eventually return home changed men to an indifferent Canadian public that, for the most part, didn’t know and didn’t care where they had been or what they had done.

The rest of their days would be spent in obscurity, waging simmering, sometimes boiling, battles to gain small, simple acknowledgements of the contributions they and other Canadians had made to combat the spread of communism.

“We were just young and very naïve kids when we signed up,” recalled Purvis, now 70. “We watched the war every night on the six o’clock news. We had just graduated from high school and we were looking around for something to do. There were no careers or jobs that were meaningful. We figured we would join the army.”

They were among thousands of Canadian citizens who served with U.S. forces in Vietnam.

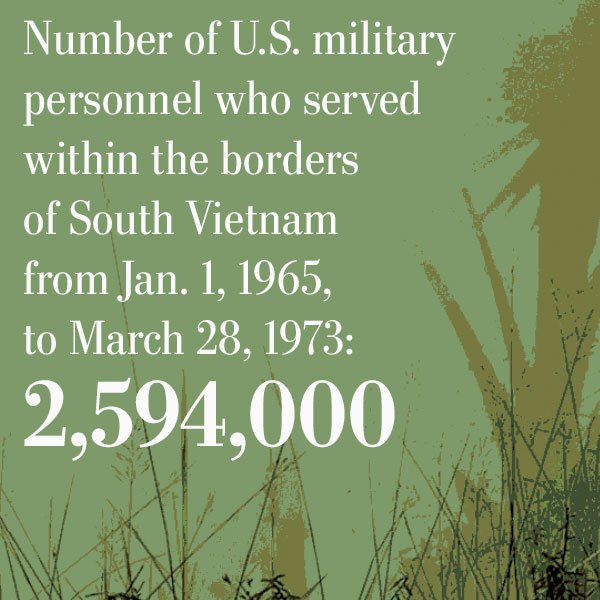

Some 30,000 Americans came north to Canada to avoid the draft, it is generally acknowledged, but estimates of the number of Canadians who went the other way to join the war range from 6,000 to 20,000. Nobody really knows how many Canadians served with U.S. forces in Vietnam and it is impossible to track, said Michael Carroll, an associate professor of history at MacEwan University in Edmonton, but he leans toward the latter figure.

Purvis’s K Company was active from Feb. 1, 1969, to Dec. 10, 1970. Ranger companies typically had 3 officers and 115 enlisted men, who patrolled in small, heavily armed reconnaissance teams deep in enemy territory. [Courtesy of Rob Purvis]

Some lived in the U.S., held dual citizenship or green cards, and were drafted. Many crossed the border to enlist in northern American cities, including Seattle, Detroit, Bangor, Maine, and Plattsburgh, N.Y. “Those cities were listed on their papers, with no mention of the fact that they were Canadian,” said Carroll.

“We just crossed the border and blended in with the American forces,” said Purvis. “When it was over, we were discharged and we were gone.”

Some, including a few Eastern European immigrants, joined out of a fervent desire to resist communism. Some Québécois and Acadians simply wanted to learn English. Some needed the work or sought adventure, like Purvis and his pals.

A significant number of First Nations men joined up, particularly from Quebec. Still others wanted to serve but either didn’t make the grade in Canada or were turned away due to federal austerity measures.

“My plan was to join the Canadian army after I got out of school in 1962,” said Ron Parkes, another Winnipegger, who enlisted with the U.S. Army at 19 in Fargo, N.D., after serving in the militia during his high-school years.

It was 1962. The Cuban Missile Crisis was on the front of newspapers around the world. Vietnam was still widely viewed as just an America advisory mission.

Parkes and some friends had gone to a Canadian Forces recruiting office in downtown Winnipeg soon after graduation. But prime minister John Diefenbaker had frozen the defence budget and “nobody could get in until somebody got out.”

“We were told there was a six-month to one-year waiting list to get in,” said Parkes. “Being the age we were, we didn’t want to wait six months to get our military careers started, so one of us had the idea of going down and seeing if the U.S. Army would take us.

“Our idea was that serving in the U.S. military would be the same as serving in the Canadian military, that we had the same values, we were allies and all the rest of it.

“The recruiting centre in Fargo said, ‘Yes, we would be happy to have you boys.’ We had no idea what we were getting into.”

Parkes became a paratrooper with the 101st Airborne Division and served a tour in Vietnam as an artilleryman. He went over in the spring of 1965 aboard a Second World War-era troop transport. The bunks were stacked four high and the trip took 20 days.

On his third night in-country, he and his mates came under heavy machine-gun fire. The tracers were flying everywhere. “I realized right then and there that I had gotten myself into something pretty serious.”

By September, they had been dropped in the middle of three battalions of Viet Cong for what was the biggest battle of the war up to that point. Thirteen paratroopers were killed and 33 wounded over three days.

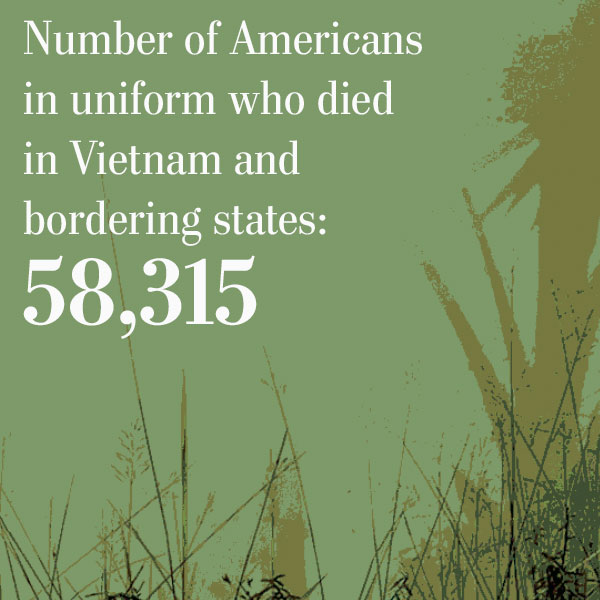

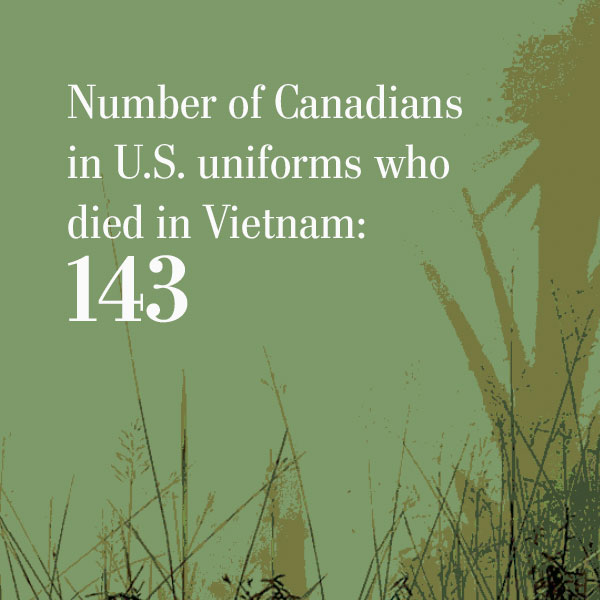

Parkes’ year-long tour concluded his three-year enlistment, and he went home. Others didn’t. The Canadian Vietnam Veterans Association (CVVA) has documented 143 Canadians killed in action with U.S. forces in Vietnam. Seven, including Marine Lance-Corporal Jonathan Peter Kmetyk, were declared missing in action.

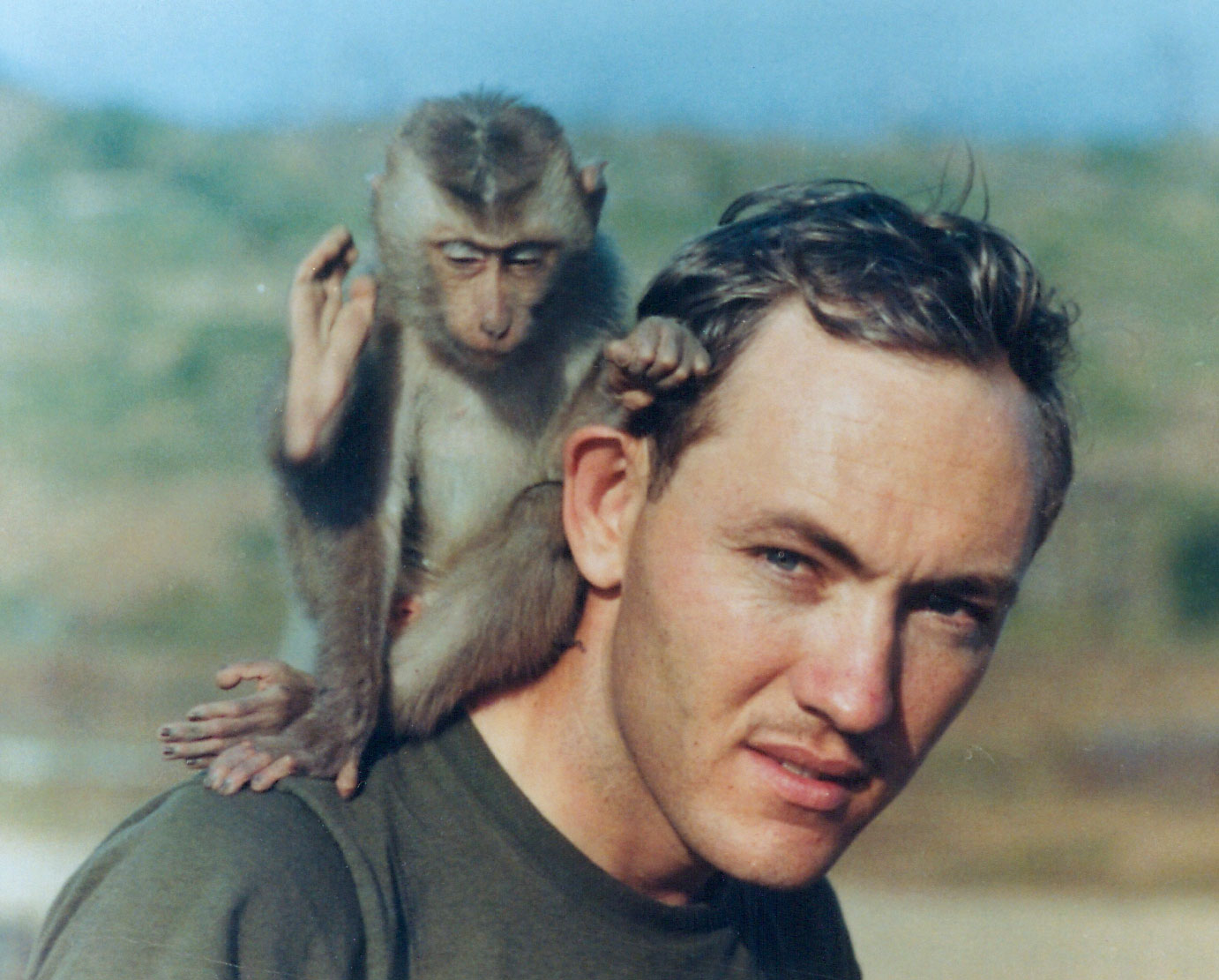

Purvis with a monkey on his back in Pleiku, Vietnam, in 1969. [Courtesy of Rob Purvis]

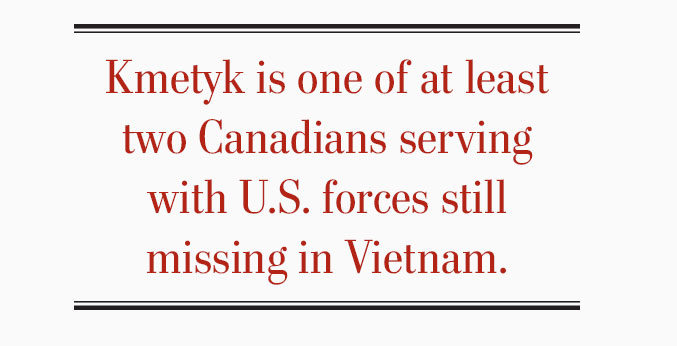

Kmetyk was from St. Catharines, Ont., but his service record lists his “home city of record” as Niagara Falls, N.Y. He was killed in an ambush during a long-range reconnaissance patrol 40 kilometres southeast of Da Nang on Nov. 14, 1967. After his death, the Marines found his mother, Vera Baranowski, in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont.

“The patrol was operating in very rugged terrain characterized by a thick growth of 30-foot trees and six- to seven-foot underbrush,” the Marine Corps headquarters in San Francisco wrote to Baranowski. “The patrol was 10 miles from the nearest friendly force, and the only way to get into or out from the area is by helicopter. Attempts were made to get a helicopter to evacuate your son’s body. However, monsoon season weather was such that the helicopter could not make the evacuation.”

Marines carried Kmetyk’s body for two kilometres through thick jungle toward a designated helicopter landing zone. They came under fire again before they could reach it. “The Marines carrying your son had to place him down and seek cover. Repeated attempts were made to get your son’s body back, but each time the effort was repulsed. One member of the patrol was wounded in the last attempt.”

A four-day search began a week later. It came up empty. Kmetyk’s remains were never found. He is one of at least two Canadians serving with U.S. forces still missing in Vietnam. He was 20 years old.

Army buddies clown around during basic training at Fort Lewis, Wash., in 1968: (from left) Billy Buffie, Larry Collins and Gerald (Butch) Buffie. Collins was killed in action in Binh Duong, South Vietnam, on May 1, 1969. [Courtesy of Ron Parkes]

Many of the Canadians who joined the American war in Vietnam, like Parkes and Kmetyk, did so before casualties began to mount and the anti-war movement gained momentum in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Technically, they were stretching Canadian law. The Foreign Enlistment Act of 1937 prohibited Canadians from enlisting in the armies of other nations, but only if they were “at war with any friendly foreign state.”

As a communist nation, North Vietnam was neither friend nor, exactly, foe. Since 1954, Canada had an official role in independent efforts to arbitrate a peace between the two Vietnams, and this would continue until after the war’s end.

“Canada, as a member of the International Control Commission, was not supposed to compromise its impartiality,” wrote Fred Gaffen in his 1990 book, Unknown Warriors: Canadians in the Vietnam War. Yet, for all intents and purposes, Canada looked the other way when it came to volunteers heading south of the 49th parallel.

The external affairs and justice departments examined the issue and refused to prosecute anyone, Gaffen wrote. They considered it “very questionable that a Canadian could be successfully prosecuted” under the circumstances of the day.

The act was originally written to prevent Canadians from fighting in the Spanish Civil War. “It was never particularly effective and to the best of my knowledge nobody has ever been convicted under the legislation,” said historian Carroll. “Modern-day cases of terror tourism or Canadians fighting on behalf of ISIS or other terrorist organizations are subject to anti-terrorism legislation.”

Winnipegger Ron Parkes in a foxhole with an M60 machine gun during his deployment in Vietnam. “We had no idea what we were getting into,” he said. [Courtesy of Ron Parkes]

In any case, like Parkes and his crew, Purvis and his buddies were welcomed with open arms. In fact, by the time they enlisted in 1968, the U.S. military had taken whatever steps it could to accommodate volunteers from Canada.

Though it couldn’t actively recruit in Canada, it did expand recruitment offices in towns and cities close to the border. Along the Quebec boundary, some American recruiting stations even put up signs that read “Bienvenue Canadiens.”

Gaffen, a former senior historian at the Canadian War Museum, describes how recruiters would write “letters of acceptability” for American military service, allowing Canadian volunteers to then receive residency visas from the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (as it was named until 2003). Those would allow them, in turn, to be inducted into the military.

“They were happy to have us,” said Purvis, who ended up in the special forces.

He served two years in the Panama jungle as part of clandestine U.S. operations spanning Central and South America. He was the last of the four friends to make the trip overseas, requesting a transfer to Vietnam after Collins died on May 1, 1969. “I wanted to go see what was going on, what he got killed for,” he said.

Purvis came to know, only too well, what it was all about and the kind of conditions and circumstances that led to his friend’s death, along with many others like him.

He spent a year in what Parkes called a 360-degree war, virtually all of it with U.S. volunteers in long-range reconnaissance. As a recon soldier in a ranger company, he worked with four-man teams, living and fighting in the jungle, without electricity or running water, sleeping when he could beneath the high, green canopy.

Purvis endured torrential rains, crushing humidity and blistering heat. He was under constant threat from bugs, snakes and a relentless enemy that was, Panama notwithstanding, far better adapted to the environs than a Canadian Prairie boy and his American comrades. He saw many friends killed and wounded.

“There were no civilians. Anything that moved or crawled was enemy.”

When his tour was up, he took a 24-hour flight stateside. He left the army on arrival. Within 48 hours of leaving Vietnam, he was on the street in Winnipeg. No one knew what he had been through. He could barely process it himself.

“I was sort of invisible when I came back,” he said. “Nobody knew anything except my family and friends. It was really a culture shock. It’s hard to describe.”

Staying in the U.S. Army, much less re-upping for another combat tour, was out of the question. He was bitter.

“Too many things happened in Vietnam, a lot of bad experiences. The politics—the reasons some people got killed and some of the stuff we did—I thought, ‘I don’t want any more of this,’ so I got out.”

Post-traumatic stress disorder hadn’t been defined in 1970. But Purvis has no doubt he’s had it. “I think everybody who went through that had some of it. Some of it still bothers me. You don’t go through an experience like that and just forget about it or walk away from it without it affecting you in some way.”

Purvis went back to school and got his Bachelor of Arts on the G.I. Bill, a U.S. program that provides educational benefits to service members, veterans and their families.

He found criminology wasn’t for him, however. He went on to work in construction, building roads, pipelines, highrises, houses and bridges from the Arctic to Los Angeles. “I couldn’t sit at a desk.”

Many Canadian veterans of Vietnam stayed in America. Regardless of where they ended up, all who served were eligible for the same benefits as American veterans, including housing, but they weren’t encouraged to seek them and many never did.

The Canadian government offered nothing, and repeatedly rejected requests to erect a memorial to the fallen. American Vietnam veterans in Detroit held a seminal “Welcome Home Canadian Veterans” event in Michigan in 1989.

The Americans launched a fundraising drive and helped finance a wall in Windsor, Ont., memorializing Canadians killed in Vietnam. The CVVA has a travelling wall it takes to veterans’ events around the continent. Canadian names also appear on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., although it bears no hometowns.

American veterans of Vietnam endured years of rejection and lack of support. The anti-war sentiment of the period blamed them as much as American policy for the atrocities that occurred, and virtually all were smeared with the “baby-killer” label until films such as Apocalypse Now, Born On the Fourth of July and The Deer Hunter cast a light on their collective experience.

In Canada, Vietnam veterans were largely ignored, until they started to make noise. What rejection and hostility they did encounter was more institutionalized and, as it turned out, more lasting than that of their American counterparts.

“We came back, and there was nothing here,” said Purvis. “Canada wasn’t involved in a war. There was no anti-war stuff here. You didn’t exist, as far as being a veteran was concerned.”

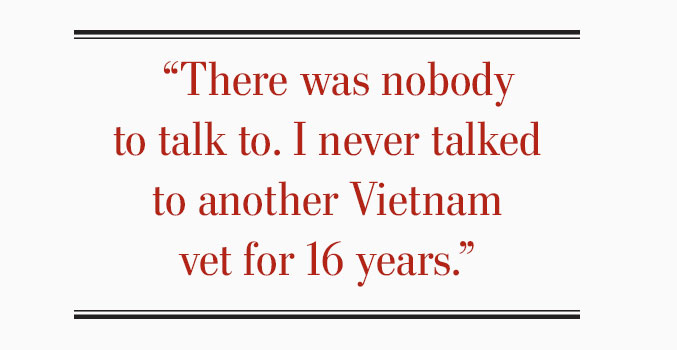

He saw his old friends, Butch and Billy Buffie. But things weren’t the same. “Everything had changed…. There was nobody to talk to. I never talked to another Vietnam vet for 16 years.”

It was the same for Parkes, who returned from 38°C temperatures and 100 per cent humidity to the deep freeze of Winnipeg in November 1966. He became an ironworker.

“I just put my service away and didn’t talk about it for about 20 years.”

“Many of the [Vietnam veterans] who returned to Canada tended to live with their experiences in obscurity,” said Carroll. “There were relatively few Canadians who could understand what they had experienced, and most wouldn’t have even understood why they went to fight in Vietnam in the first place, especially as the war went on and things went from bad to worse after 1968.”

They began to emerge from the woodwork when Purvis and others formed the CVVA after a reunion in Washington, D.C., in 1986. The group became affiliated with the ex-service organization Army, Navy and Air Force Veterans in Canada in 1988 and marched on Remembrance Day for the first time.

Purvis attended a reunion of Canadian Vietnam veterans in Washington, D.C., in 1986, which led to the creation of the Canadian Vietnam Veterans Association. [Courtesy of Rob Purvis]

Purvis and Parkes lobbied the U.S. government for medical benefits for Canadian Vietnam veterans. In April 1987, with help from the American Legion and others, they got a bill, S.894, through Congress and signed by the president, effectively providing medical benefits to non-citizens who served in U.S. forces.

“Throughout our history, citizens of other countries have joined us in the defence of liberty,” said Senator Frank Murkowski, who tabled the bill. He credited Canadian veterans of Vietnam for bringing the issue to his attention. “All who serve, irrespective of citizenship, should have access to medical care for the disabilities incurred while fulfilling that oath [of duty] whether they live in the United States or a foreign country.”

Once a service-related claim is established with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Canadian Vietnam veterans may receive care at facilities administered by Veterans Affairs Canada.

Canadians who fought in Vietnam still struggle for even the most modest recognition and acknowledgements at home, including the right to be buried alongside other veterans in cemeteries from Nova Scotia to British Columbia.

Only Quebec and Ontario explicitly permit them veterans’ licence plates. Manitoba approved Parkes’ application for one, then recalled it a year later. He had to return it. When a U.S. Vietnam veteran in Oregon read about the humiliation, he sent Parkes an old set of his own for the back window of his truck.

The years of lobbying and helping Vietnam veterans navigate the system and gain benefits are drawing to a close, however. Once hundreds strong with chapters across the country, membership in the CVVA has dropped below 50 individuals at a couple of remaining chapters.

Many have died, a disproportionate number from the effects of Agent Orange, the Canadian-tested defoliant used in Vietnam that is responsible for numerous illnesses, including some leukemias, Type 2 diabetes, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Parkinson’s disease, prostate cancer and respiratory cancers. “It’s still killing them,” said Purvis.

Purvis returned to Vietnam with his wife and son in 1994. The American embargo on travel to the now-unified communist country was lifted while he was getting their visas in Bangkok. No Americans to speak of had been back at that time.

“I just woke up one morning and said, ‘I have to go.’ We went two weeks later and backpacked from Saigon to Hanoi. We spent a month there.

“My tour guide was North Vietnamese Army; my driver was South Vietnamese Army; I was in the American army. And we all sat down and had a beer together. It was pretty strange. The people were nice; it’s a beautiful country.”

In many ways, the trip was a healing experience for Purvis. While he still battles demons from his warfighting days, he returned home with a sense of peace he hadn’t known in a long time.

His school chum Larry Collins was buried in the Field of Honour at Winnipeg’s Brookside Cemetery, alongside Canadian veterans of the world wars, Korea and Afghanistan.

Except for the friends he lost, Purvis said, he has no regrets.

“It’s a decision I made. Everybody makes decisions in life and you have to live with them. There were a lot of positives—the camaraderie, the people I met. In two or three years, I had more life experiences than most people get in a lifetime.”

U.S. troops patrol a jungle trail during Operation Junction City—an attempt to locate Viet Cong headquarters in 1967. [AP Photo]

Canadians served with the Nile Expedition to Sudan. [Alamy/AT2P9H]

Foreign Fighters

Canadians have a long history of involvement in the militaries and wars of nations other than Britain, predating Confederation. Here are some highlights:

The American Civil War.[Alamy/EX6XAH]

• The American Civil War, 1861-1865. Queen Victoria declared in May 1861 that Britain would not involve itself in the war between the states. An indeterminate number of Canadians nevertheless enlisted in the armies of both the North and the South. One of the rare instances when some Canadians won and some lost the same war.

Lieutenant Hugh Murray (right) fought with the Papal Zouaves in Rome in the 1860s and 1870s. [Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec]

• The Papal Zouaves, 1868-1870. Some 400 Canadians, mostly francophones in Quebec, joined volunteers from the world over in Rome to defend what was then papal territory in the face of a movement to unify Italy. Their army was known as the Papal Zouaves. Nine Canadians died, mainly from disease, and the defence failed when French troops withdrew to fight the Franco-Prussian War. The Papal States were incorporated into Italy and The Holy See was ultimately left with 44 hectares—the State of Vatican City.

• The Nile Voyageurs, 1884-1885. The first instance of a distinct Canadian contingent sent to help Britain in an overseas conflict was this group of about 400 voyageurs, including about 60 Iroquois from Kahnawake, Que., recruited by Lord Lansdowne to rescue the British general, Charles Gordon, a former governor general of Sudan who was besieged by Muslim rebels in Khartoum. The city was captured and Gordon was killed before they got there. The general was played by Charlton Heston in the 1966 movie Khartoum.

The Spanish Civil War. [Alamy/AT2P9H]

• The Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. Some 1,200 Canadians of various ethnic origins fought mainly for the Loyalists, while a few fought for Franco’s Nationalists. Like the Zouaves, they were not recognized by Ottawa and the Foreign Enlistment Act of 1937 expressly forbade their participation. More than a third were killed. None are believed to have been prosecuted under the act. Another instance of Canadians winning and losing.

A U.S. military Bell UH-1 Iroquois (Huey) helicopter sprays Agent Orange defoliant over agricultural land in Vietnam. [Wikimedia]

Impartial contributions

Canada’s relationship with the Vietnam War was complicated. As a member of the three-country International Control Commission, it remained officially impartial throughout the conflict. But it allowed Canadians to enlist with American forces fighting in Vietnam and provided $29 million in aid to South Vietnam between 1950 and 1975.

The aid was part of the Free World Assistance Program co-ordinated by the United States State Department and the Pentagon’s International Security Office. In the field, it was administered by the International Military Assistance Force Office in Saigon.

Ottawa stopped the shipment of medical relief to civilian victims of the war in North Vietnam several times. Other involvement by Canada in Vietnam included:

• 500 Canadian firms sold $2.5 billion worth of war materiel (ammunition, napalm, aircraft engines and explosives) to the Pentagon. Another $10 billion in food, beverages, berets and boots was exported to the U.S., along with nickel, copper, lead, brass and oil for shell casings, wiring, plate armour and military transport.

• Canada’s unemployment rate fell to a record low of 3.9 per cent, gross domestic product rose six per cent annually, and capital expenditure expanded exponentially in manufacturing and mining as U.S. firms invested more than $3 billion in Canada to offset shrinking domestic capacity due to the war.

• The herbicide Agent Orange was tested for use in Vietnam at CFB Gagetown in New Brunswick. American bomber pilots trained at carpet-bombing runs over Alberta and Saskatchewan before their tours of duty in Southeast Asia.

• The results of the only successful peace initiative to Hanoi, North Vietnam, conducted over several trips by Canadian diplomat Chester Ronning in 1965 and 1966, were kept from public knowledge so as not to harm official Canada–U.S. relations.

• Canada admitted more than 5,600 South Vietnamese in 1975 and 1976, mainly migrants with relatives already living in Canada.

• Beginning in 1979, Canada welcomed about 60,000 Vietnamese refugees from among a second wave of migrants known as boat people, who fled the country via dangerous sea voyages to Hong Kong and elsewhere.

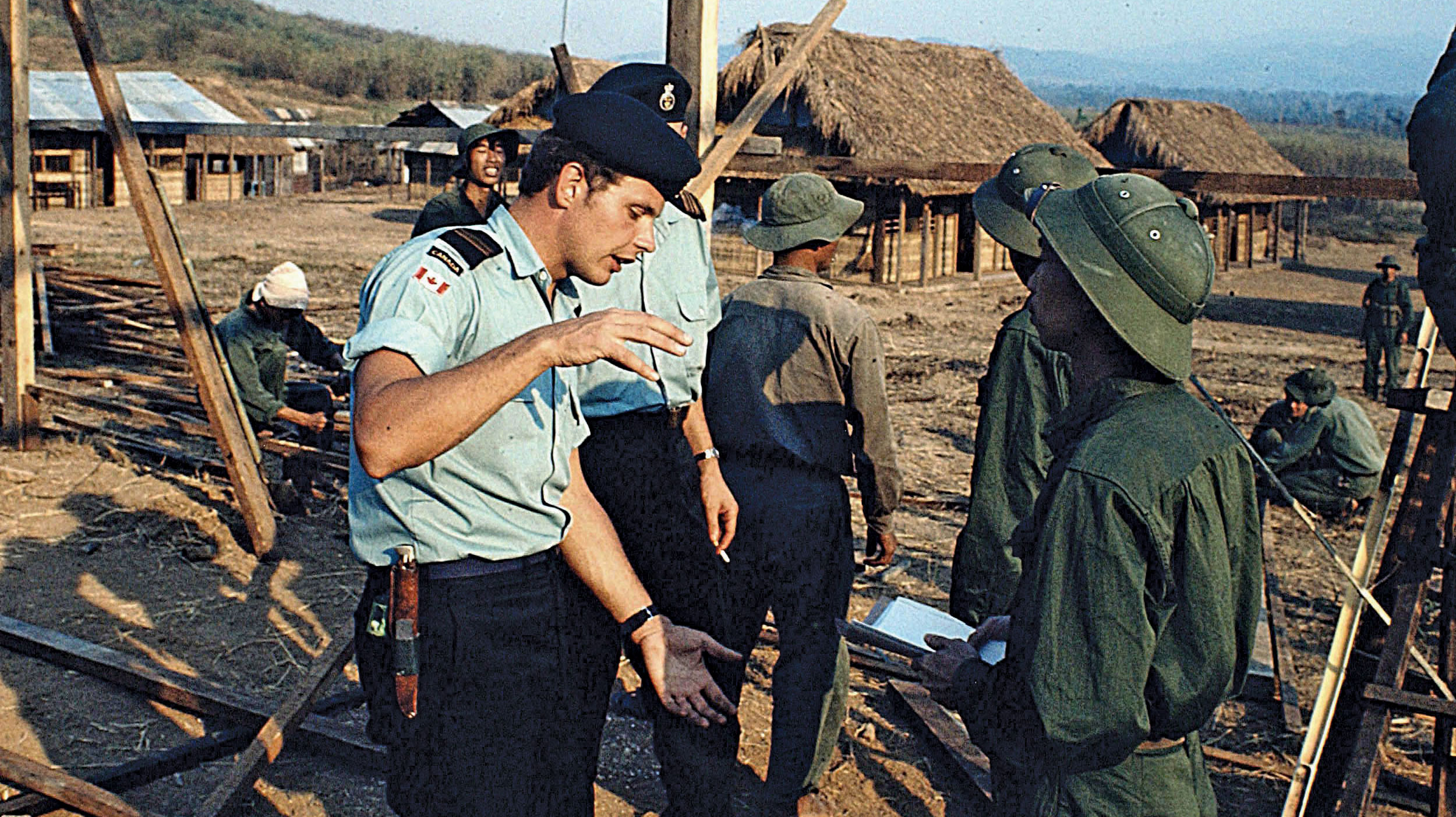

Canadian officers speak with Viet Cong soldiers in March 1973, following the U.S. pullout. [Peter Bregg/The Canadian Press]

Canada’s early peacekeepers

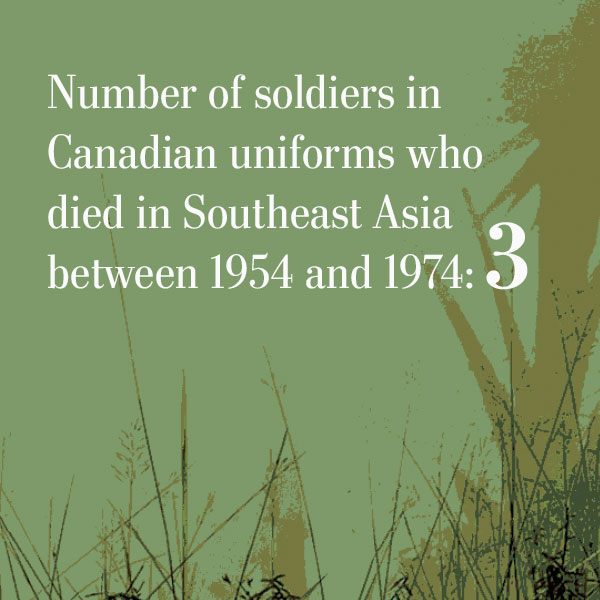

Canada, charged with keeping the peace in former French Indochina in 1954, was one of three nations responsible for implementing thedivision of Vietnam that ultimately started a war lasting 19 years, five months and 29 days.

Over that time, as many as 20,000 Canadians joined American forces fighting in Vietnam, while a few thousand members of Canada’s armed forces maintained a continuous presence in Indochina that predated United States military action and continued until the Americans left.

Canada’s role in Vietnam began in July 1954 with the three-member International Control Commission (ICC). Poland and India were the other contributors to the force of about 1,400. It was appointed under the Geneva Accords.

Their job: maintain the treaty that ended the war between France and communist-backed troops seeking independence in French Indochina. Their area of responsibility, under what were actually three commissions: North and South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia.

They predated Canada’s first official peacekeeping force, deployed two years before Canada took over the UN-sanctioned role in the Suez Crisis of 1956 that earned Lester B. Pearson the Nobel Peace Prize.

“They were really starting peacekeeping from scratch,” said John MacFarlane, a historian at the Department of National Defence who is writing an official history of Canadian military service in Vietnam.

The Geneva Agreements of 1954 partitioned Vietnam along the 17th parallel. They mandated reunification elections in 1956. Neither the U.S. nor South Vietnam signed the agreements, however, and the elections never happened. They would ultimately go to war against the North to prevent a communist takeover of South Vietnam.

The ICC’s first responsibility was to implement Vietnam’s division, with the communist North controlled by the People’s Army of Vietnam and the South by what was then known as the French Union, made up of French forces, Foreign Legion and others.

This daunting process included the mass relocation of nearly 900,000 people, all but 4,200 of them heading from north to south.

That was supposed to be the end of it for the commission. But with tensions between the two Vietnams escalating, the members stayed on. They remained until 1973, a poorly funded, under-manned and ultimately ineffectual force that could do little more than stand by as an undeclared proxy war developed between the forces of communism and western democracy.

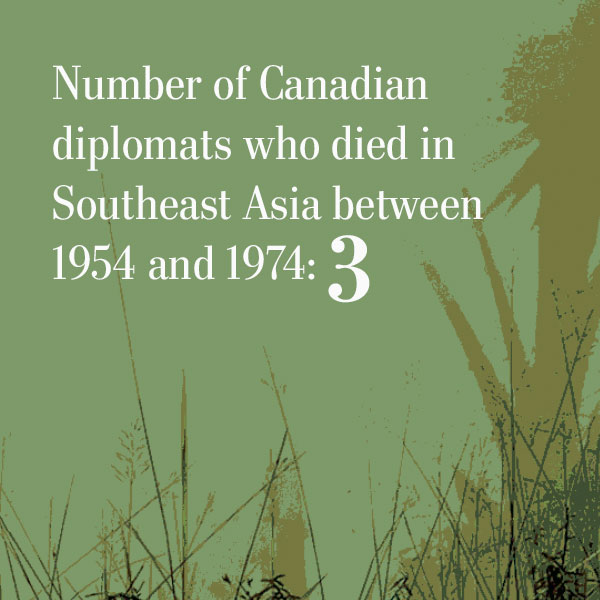

But the ICC was not without its casualties. Canadian diplomat John H. Thurrott died in a car accident in Laos on Christmas Eve 1954, and diplomat Albert E.L. Cannon was murdered on April 12, 1957. Cannon’s death spawned an RCMP investigation that led to new rules restricting Canadians’ movements after dark.

On Oct. 18, 1965, an aircraft carrying nine ICC members—three Canadians, five Indians and a Pole—along with four French crew disappeared on a flight from Vientiane, Laos, to Hanoi, North Vietnam. Officials surmised their Boeing Stratoliner was shot down after the Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese leadership denied searchers for the wreck site access to their airspace.

The Canadian casualties were diplomat John D. Turner, a permanent representative in Hanoi; Sergeant James S. Bryne of Toronto, and Corporal Vernon J. Perkin of London, Ont. Their bodies were never recovered.

The commission’s ultimate demise came after India normalized relations with North Vietnam but not the South. The Saigon government subsequently expelled the Indians and, by extension, all commission members. They withdrew to Hanoi—where their irrelevance became all the more apparent.

Helping maintain the treaty that ended the French Indochina war, Lieutenant-Colonel D.H. Frink reviews a map with officers from the communist Pathet Lao (left) and the Royal Lao Army (right) in 1956. [CDND/LAC/PA-151202]

The ICC was shut down and, under the Paris Peace Accords signed on Jan. 27, 1973, replaced with the four-member International Commission of Control and Supervision (ICCS). Canada and Poland stayed on, joined by Hungary and Indonesia.

Canada was officially an ICCS member for about six months, until Iran took its place.

Ottawa had wanted to leave Vietnam as early as April 1973 after supervising the U.S. withdrawal and prisoner exchange, completed on March 31, but remained, said MacFarlane, “so as not to give the impression of participating only for this reason.

“By 1968, everyone was looking for peace after the Tet Offensive,” said MacFarlane. “So, the Canadians who were there…declined in number and for those who stayed, their main mission from 1968 until 1973 was really to set up the conditions that would lead to a peace deal that would help the Americans withdraw with honour. And that’s a very different mandate than what we signed up for in 1954.”

A Canadian ICCS member, Captain Charles Laviolette of Saint-Omer, Que., was killed along with eight others when their helicopter was shot down over South Vietnam on April 7, 1973.

A veteran is a veteran

It took time and walls of misunderstanding to overcome, but Canadian veterans of American forces in Vietnam were finally granted the right to full voting membership in The Royal Canadian Legion in 1994.

After years of debate and grassroots advocacy, it was a resolution from Ontario Command that passed with little fanfare at the Dominion convention in Calgary and opened the doors to what to this day remains a largely unknown group.

Resolution 322 “allows Vietnam War veterans who were Canadian citizens who had served with the American, Australian, Korean or South Vietnamese armed forces and who retain their Canadian citizenship to become ordinary members.”

Dave Gordon, an Ontario deputy district commander when he attended the 1994 convention, said it was an idea that had reached its time. “It’s always the thought that a veteran is a veteran is a veteran, so it had to come to be.”

Those who fought with American forces in Vietnam are not eligible for Canadian veterans’ benefits, or even plots in cemeteries recognized by Ottawa.

Yet they can claim benefits and support from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, where the American Legion and Vietnam veterans’ groups are best suited to go to bat for them. Given federal policy in Ottawa, the RCL’s advocacy role on behalf of those who served with U.S. forces has always been limited.

And while provincial commands review and process applications for veterans’ licence plates, it is provincial governments that make the policy on who qualifies. Only the provincial governments of Quebec and Ontario explicitly grant veterans’ plates to those who served with U.S. forces in Vietnam, while Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador grant them to anyone who served with “a wartime ally of Canada.”

The consensus opinion was that the U.S. was a Cold War ally and that Vietnam was an extension of the war against communism.

The RCL broadened its definition of a veteran in 2014 to include those who had served with a wartime ally.

Advertisement