Captain Jennifer Casey, Snowbirds public affairs officer, was killed in the crash of a Tutor jet on May 17, 2020. [DND]

Both air crew escaped the CT-114 Tutor as it went down on takeoff near Kamloops, B.C., on May 17, 2020. But they were low and Captain Jennifer Casey—the team’s public affairs officer—was killed after she is believed to have become briefly entangled with her ejection seat and her parachute failed to fully open. The pilot, Capt. Richard MacDougall, landed on the roof of a house and was badly injured.

“Upon loss of power, the pilot initiated a climb straight ahead and then a turn back towards the airport,” said a Defence Department statement. “During this maneuver, the aircraft entered into an aerodynamic stall and the pilot gave the order to abandon the aircraft.

“The pilot and passenger ejected…at low altitude and in conditions that were outside safe ejection seat operation parameters. Neither the pilot nor the passenger had the requisite time for their parachutes to function as designed.”

The plane crashed in a residential area. No one on the ground was hurt.

The 47-page report was produced after an investigation by the Royal Canadian Air Force Directorate of Flight Safety, the military’s airworthiness investigative authority.

The document makes five preventative and safety-oriented recommendations, three of which address operations; two focus on the aircraft and its systems.

Flights by what is officially dubbed 431 (Air Demonstration) Squadron were temporarily suspended after the accident. The team was training at 15 Wing in Moose Jaw, Sask., for the 2021 show season when the report was released.

DNA evidence…confirmed a brightly coloured bird known as a western tanager.

The report said Casey blurted the word “bird” following a “loud, impact-like sound” just after they took off from Kamloops Airport, then the aircraft lost thrust.

Video taken from the ground appeared to show a small songbird entering the engine.

DNA evidence collected from the engine’s internal components confirmed a brightly coloured bird known as a western tanager—average weight, 24-36 grams—had been sucked into the engine’s intake, but the report said the damage it caused would not have precipitated a catastrophic failure. Rather, it resulted in a compressor stall that was never cleared. The plane was at about 58 metres (190 feet) above ground at the time.

A western tanager (Piranga ludoviciana) struck the aircraft’s engine. [Flight Safety Investigation Report/CT114161]

It also recommended further training on engine-related emergencies on takeoff and low-level flight, including clarifying the command to eject.

MacDougall continued climbing after the bird strike, reaching about 244 metres (800 feet) above ground, then began turning the aircraft 180 degrees back toward the airport and away from populated areas. The manoeuvre cost the crew altitude and airspeed.

“After a slight pause, the aircraft then rolled rapidly in the same direction through 270 degrees ending upright but with a 45-degree nose-down angle.”

Realizing the situation was unrecoverable, MacDougall issued the command “pull the handle,” rather than the commonly used “EJECT-EJECT-EJECT.”

“The format of this command is designed so that the passenger initiates ejection upon hearing the first ‘EJECT’ of the command followed by the pilot on the third ‘EJECT,’ who initiates their own ejection,” the investigators wrote. “This difference in wording may have contributed to the overall confusion/uncertainty of the situation which resulted in the passenger ejecting second.”

The investigation found that Casey ejected at 120 metres (394 feet) above ground, 0.4 seconds after and 15 metres (50 feet) lower than the pilot. Her seat flew backwards for a time after leaving the aircraft. The plane was less than three seconds from impact.

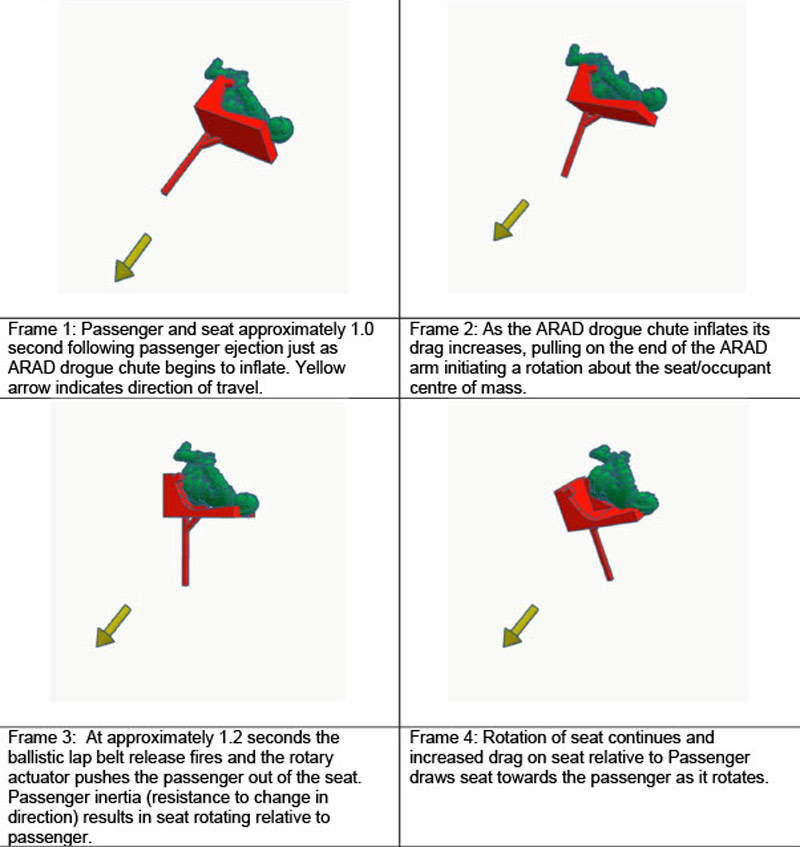

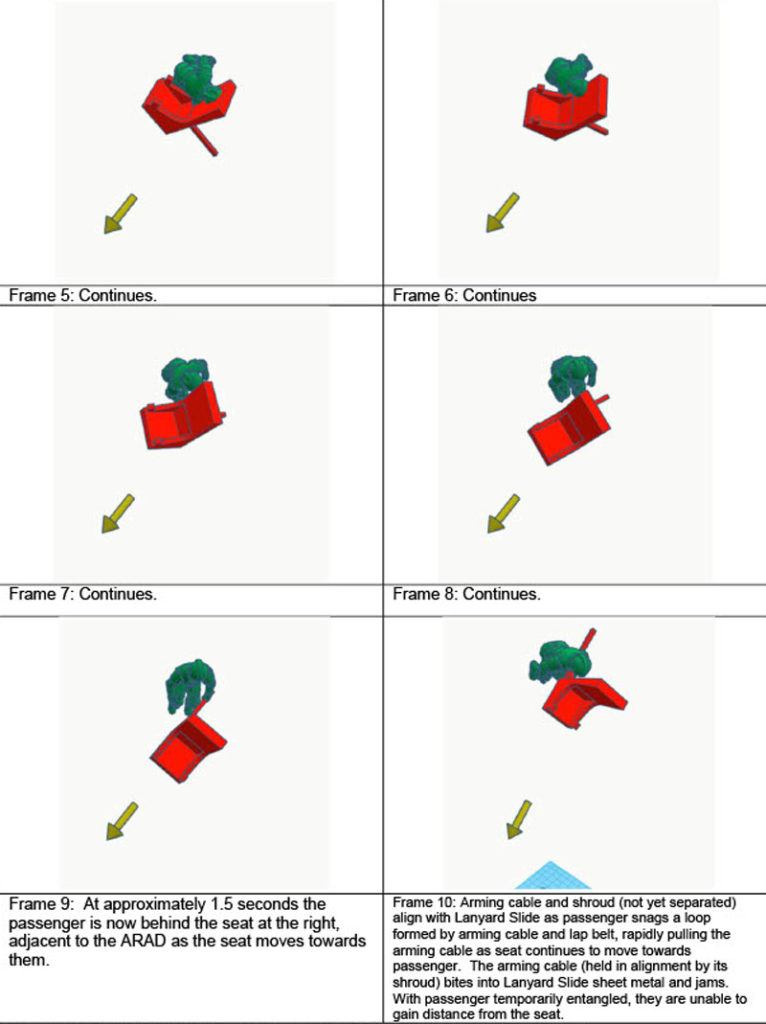

“The passenger did not achieve the requisite amount of separation from the seat during the ejection sequence,” it said, explaining that the seat rolled on its vertical axis during the ejection, reversing its orientation.

“The reverse direction of the seat prevented the aero rigid arm drogue (ARAD) chute from catching the wind and pulling the seat away from the occupant. The chute did eventually release, however, not without causing the seat to rotate back towards its original trajectory thereby potentially causing a collision with the passenger as well as a temporary entanglement, further preventing normal distancing.”

A step-by-step diagram shows the movement of the passenger’s ejection seat. [Flight Safety Investigation Report/CT114161]

The investigators were somewhat baffled as to why the seat performed as it did, offering three possible explanations: that objects stored between the seat and the side of the aircraft interfered with the ejection; that the aircraft itself or a disturbance in the airflow changed its direction; that Casey’s arm or leg extended into the airstream causing a yaw just before the drogue deployed.

The investigators concluded that the last scenario was the most likely.

“A combination of deceleration through obstructions and impact with the ground resulted injuries to the passenger which were not survivable,” they wrote.

Both parachutes still had packing creases, indicating “a very low speed opening and not being fully inflated at time of impact.”

The roof’s slope and its construction absorbed the pilot’s impact, “reducing the effects of a rapid deceleration and subsequent trauma on the human body.”

“The passenger’s parachute pilot chute was completely destroyed and the spring in [her] pilot chute was ripped out of the fabric,” said the report. “The kicker plate was 22 ft. from the same tree that the seat went through, indicating that the parachute most likely opened as the occupant passed over the tree but without sufficient altitude for it to inflate open.”

Debris was spread over two city blocks.

The investigators recommended a directive clarifying how pilots should prioritize an ejection-scenario near or over a populated area, and research into ways to stabilize ejection seats from any tendencies to pitch, roll or yaw.

They also recommended that the practice of storing items between ejection seats and airframe walls cease immediately.

Debris was spread over two city blocks, with the canopy, aircraft and ejection seats landing in a relatively straight line along about 150 metres.

The plane’s data acquisition unit, a non-crashworthy device which records and processes flight data similar to a commercial aircraft’s black box, was too damaged to extract any useful information.

The ejection seats landed on neighbouring properties, about 100 metres northeast of the crash site. One caused minor damage to a fence, while the other damaged a tree and “left a significant impact scar in the backyard.”

The crash site in Kamloops, B.C. [Flight Safety Investigation Report/CT114161]

The Snowbirds’ signature two-seat Tutors were used as training aircraft by the RCAF from 1963 until 2000. They’re powered by a single General Electric J85-CAN-40 axial flow turbojet engine, installed in the centre fuselage.

The planes have been modified to be used as a single-pilot airshow aircraft.

Plans were recently approved to modernize the Tutors and extend their lives until 2030. The $30-million project will equip the planes with new avionics and instrumentation, as well as glass cockpits to bring them in line with federal air regulations. A separate project is underway to upgrade their parachute and harness designs.

Advertisement