The air war was the nursery of Canada’s bush flying heritage

Since 1973, Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame in Wetaskiwin, Alta., has honoured more than 200 individuals who contributed to the nation’s aerial achievements, progress and heritage, including pilots, executives, designers and writers. More are added each year. The Hall’s website is spartan in describing their achievements, but a book, They Led The Way (1999), is more detailed. Even so, the literature for most inductees focuses on the peacetime work that led to their nomination. There is room to ponder those with First World War flying origins.

Stuart Graham (1896-1976) was Canada’s first bush pilot. In 1919, he flew a former U.S. Navy Curtiss HS-2L in stages from Dartmouth, N.S., to Grande-Mère, Que. Using an improvised base on Lac-à-la-Tortue, Que., he pioneered aerial forestry surveys and fire patrols. The airfield there now hosts an excellent museum of pioneer commercial flight. Graham was subsequently involved in numerous aerial firms, supervised development of British Commonwealth Air Training Plan airfields in 1939-45, and was prominent in the postwar work of the International Civil Aeronautical Organization. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1976 and in 1991 was posthumously awarded the Trans-Canada Trophy (McKee Trophy) by the Canadian Aeronautics and Space Institute for lifetime achievement. His honours included the Air Force Cross (November 1918) and Officer, Order of the British Empire (July 1946).

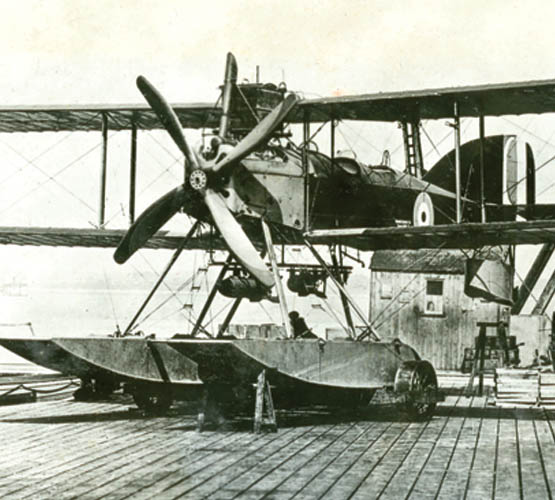

But before all that, Graham was a soldier, wounded by a sniper in March 1916 and sent to England. There was a Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) station near his hospital and it inspired him to transfer to that service in October 1917. He soloed after only six hours of instruction and was posted to RNAS Calshot near Southampton to learn the ways of seaplanes and flying boats. From there, and later from the RNAS seaplane base Cattewater near Plymouth, he flew Short 184 two-seat floatplanes on anti-submarine sorties. He wrote an account of his adventures, which was finally published in the summer 1999 issue of the Journal of the Canadian Aviation Historical Society.

Most of Graham’s patrols lasted about three hours, but a few exceeded five. A sortie on Aug. 31, 1918, was five hours and 45 minutes, took him to the Channel Islands and back, and exhausted his fuel. It was often foggy, the engines were unreliable, Morse radio communication was sporadic, and the pigeons carried for emergencies were vulnerable to hawks and falcons. On three occasions, he force-landed in the English Channel. On the first, on May 17, 1918, he taxied several hours to reach his base; he was lucky the sea was calm that night. On May 19, he was towed home by a destroyer. On June 6, he repaired the engine and took off again.

Stuart Graham flew Short Admiralty Type 184 floatplanes (top photo) on anti-submarine missions. Postwar, he was Canada’s first bush pilot. [AC/PA-089126]

Graham’s job was to hunt German submarines, and on April 22, 1918, he found one on the surface. He dropped two 230-pound bombs and one 100-pound bomb, which exploded 10 seconds after the U-boat submerged. “Our aircraft was suddenly going upward like an elevator, though judging by the way the wings were flapping, it was more like a seagull,” he recalled. He made another promising attack on May 27, this time turning sharply to avoid the blasts of his own bombs. Thereafter, the closest thing that he saw resembling a submarine was a large, dead whale.

Graham flew 355 hours before he was demobilized. In the summer of 1918, he applied to join the Royal Canadian Naval Air Service, then forming in Canada. His submission caused consternation in Royal Air Force circles, which worried about losing experienced aircrew to a new national force.

On Nov. 6, 1918, an American naval air ensign permitted him to fly an HS-2 flying boat. “Very nice to fly and very stable” he wrote. Even then he was planning a postwar commercial flying role, and it was natural that he would launch it with that flight from Dartmouth to Grande-Mère.

“Punch” Dickins, a First World War ace, pioneered aerial survey flights across Northern Canada. [19940003-822; Archives of Manitoba]

Another pioneering commercial pilot was Clennell Haggerston “Punch” Dickins (1899-1995). Frontier flying at the time tended to follow water routes on a north-south axis, a precaution where magnetic compasses were unreliable. In 1928, Dickins undertook a dramatic survey flight from Baker Lake to Fort Smith, from east to west across the Barren Lands. It earned him the McKee Trophy for that year. It also launched him on a brilliant career that would include flights along the Arctic coast, managerial positions with Canadian Pacific Air Lines and de Havilland Canada, and helping establish the system that delivered thousands of wartime aircraft to Britain. Along the way, he would earn appointment as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1935 and as an Officer of the Order of Canada in 1968. All this sprang from his First World War experiences.

In university, Dickins waited impatiently to turn 18 so he could enlist in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, which he did in March 1917. Once overseas, he followed his older brother Francis into the Royal Flying Corps.

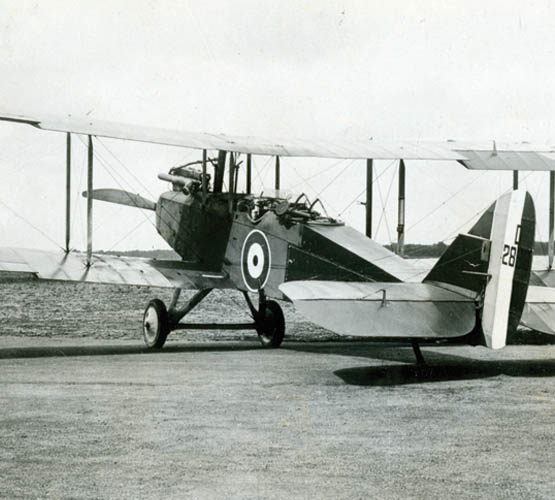

Following ground instruction at Oxford, Dickins was introduced to flight at RAF No. 25 Training Squadron at Thetford in Norfolk, flying ancient Henry Farman biplanes (“a lot of piano wire and bamboo,” he recalled), then Airco DH.6 trainers, followed by operational instruction on veteran Royal Aircraft Factory BE.2c and RE.8 army cooperation aircraft. On May 23, 1918, he reported to No. 211 Squadron at Dunkirk on the coast of France. He was to be a bomber and reconnaissance pilot, flying de Havilland DH.9 aircraft.

“Punch” Dickins flew the DH.9 bomber, raiding German submarine docks in Belgium. After the war, he flew airmail trials. [CWM/19940003-761]

It was often foggy,

the engines were unreliable…

and the pigeons carried for emergencies were vulnerable

to hawks and falcons.

The DH.9 was armed with a .303 Vickers machine gun synchronized to fire through the propeller arc and a .303 Lewis gun in the rear cockpit. It normally carried four 112-pound bombs under the wings, dropped from about 12,000 feet. No. 211’s raids were chiefly on the German submarine docks in Belgium at Bruges, Zeebrugge and Ostende. Postwar analysis showed that the incessant attacks were a nuisance to the enemy, but were not as effective as believed at the time.

The bombers flew in groups of five to twelve aircraft. Much stress was laid on formation maintenance to defend against German fighters; dogfighting was out of the question. Pilots could barely manoeuvre to avoid attacks and were lucky when an enemy aircraft flew into their sights. The principal defence of formations lay in the gunners, who could swivel their weapons in any direction. On one occasion, Dickins’ machine was badly shot up, with some bracing wires cut. “It sagged when we landed,” he recalled, “but it held together in the air.”

On Oct. 24, the squadron moved inland to Clary, a commune in northern France. Reconnaissance and photography missions dominated the last few weeks of the war. Casualties and transfers had made Dickins one of the “old men” of No. 211.

In June 1919, the London Gazette announced the award of the Distinguished Flying Cross to Second Lieutenant Dickins. There was no published citation other than “in recognition of distinguished services rendered during the war.” Even he did not know exactly why he had been decorated, and inquiries years later, directed to the British Air Ministry, failed to provide an answer. Buried in RAF files was the recommendation that his commanding officer had drafted in January 1919:

This officer has flown with his squadron for 240 hours and has taken part in 71 successful bomb raids and ten photographic reconnaissances. He and his observer have shot down four enemy aircraft, and he has proved himself a thoroughly brave and conscientious pilot. On the 4th November 1918, whilst on a photographic reconnaissance, his formation was attacked by ten enemy aircraft, one of which he shot down in flames. On the 29th September 1918, he led a flight of the formation which set out to bomb Courtrai Station. After successfully bombing the objective, his formation was attacked by 40 to 50 enemy aircraft. It was owing to his brilliant leadership that his formation returned without loss while his observer shot down one of the enemy.”

Not bad for a 20-year old Second Lieutenant!

One scarcely needs to describe the wartime career of Wilfred Reid “Wop” May (1896-1952), bush pilot extraordinaire, possibly the father of organized Canadian search-and-rescue methods, McKee Trophy winner for 1927, and Hall of Fame inductee. He is frequently remembered as the man that Baron Manfred von Richthofen was chasing when the Red Baron was shot down and killed—possibly a victim of target fixation. May went on to earn a Distinguished Flying Cross, credited with at least seven enemy aircraft destroyed while serving in No. 209 Squadron. He was profiled in Wings of a Hero: Canada’s Pioneer Flying Ace, Wilfred Wop May, a detailed 1997 biography by Shiela Reid.

After the First World War, “Wop” May opened Canada’s first registered aircraft company, May Airplanes Ltd. [Courtesy of the “Wop” May Collection]

Less well known is another member of the Hall of Fame bush pilot pantheon, Kenneth Foster Saunders (1893-1974). He was active as chief test pilot for Fairchild Aerial Surveys from 1923 to 1936, engaged in aerial mapping. Later he was a regular flying visitor to communities along the North Shore of the St. Lawrence. In 1936, he joined the new Department of Transport, forsaking his frontier operations for administrative duties in Vancouver and Edmonton.

Saunders embarked on his career in 1915 as a pupil at the Wright Flying School in Dayton, Ohio. He paid for his lessons and an Aero Club of America certificate. With that in hand, he qualified for a commission in the Royal Naval Air Service, plus a partial refund of his expenses. He sailed for England and RNAS flight training at the Naval Flying School, Eastchurch on the Isle of Sheppey. In August 1916, he was posted to HMS Ark Royal, a former merchant ship that had been converted to a seaplane tender and was destined for extensive operations in the eastern Mediterranean.

Here one despairs of the Royal Navy’s well-earned reputation of being the “silent service.” His time on Ark Royal is uncertain, and precisely what he did is obscure. In May 1918, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross “for gallantry and devotion to duty during the period from July 1 to December 31, 1917.” By the end of 1917 (and perhaps earlier), he had returned to Eastchurch as an instructor. In November 1918, he was awarded an Air Force Cross “in recognition of valuable flying services.”

Test pilot and aerial mapper Kenneth Saunders, poses with a Curtiss JN-4. [Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame]

Again, specifics are missing but clues are found in a report by his commanding officer dated Feb. 1, 1918. It speaks of his “exceptional zeal and ability in connection with training.” In the previous six months, he had flown 250 hours. Saunders had gone beyond teaching. “He has shown great energy and skill both day and night in going up after hostile machines and on one occasion found and attacked a formation of Gothas [bombers] by night.”

Advertisement