The best part of my job without a doubt is meeting veterans. The vanishing generation of men and women who served in the Second World War and Korea holds a special place in my heart. They’ll soon be gone, and every opportunity to sit down with a soldier, sailor or air force veteran of those wars—of any war, to be sure—is to be cherished. Many, like Elmer Auld, are in their late-90s; some are 100 or more. For a surprising number, their wartime memories remain vivid. Such was the case with Auld, a sonar operator aboard a corvette on the notorious North Atlantic Run—a U-boat hunter, a terrific interview and my favourite column of 2022.

Elmer Auld, 98, of Thunder Bay, Ont., says he thinks of the war at sea every day. His experiences as a U-boat hunter aboard an escort vessel on transatlantic convoy duty fostered a lifelong appreciation for the little things in life.

[Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

They’d be there when Able Seaman Elmer Auld landed on the bridge for his early-morning watch aboard the corvette Giffard—seven U-boats somewhere out in the mid-Atlantic, beyond the cover of air patrols, in an area known as “The Black Hole.”

Then, almost as if they had waited for his arrival on deck, the German wolf packs would disappear beneath the waves and “it”—the hunt—was on.

Auld, a native of Port Arthur, now part of Thunder Bay, Ont., was the hunter, a teenaged ASDIC operator on the notorious North Atlantic Run, escorting convoys of merchant ships between St. John’s, Nfld., and the British Isles.

The ASDIC set, an early form of sonar, used echolocation to find submarines.

Auld would scan the ocean ahead on an arc, transmitting the telltale pings every 10 degrees from “green three-oh to red three-oh” (starboard 30 degrees to 30 degrees port), waiting for the distinctive clang when they found a U-boat.

The time it took the signal to bounce back reflected the distance the sub was from the warship.

“It was a hammer hitting a barrel type of thing,” Auld, a spry 98 years old, told Legion Magazine. “It was loud and clear. You knew it was steel; it wasn’t a fish. It came back as a good echo.”

Death was always lurking somewhere beneath the waves.

Able Seaman Elmer Auld was 17 when he joined the navy in 1941. He sailed aboard a minesweeper, Fairmile B motor launches off Newfoundland and as an ASDIC operator on the North Atlantic Run aboard the corvette Giffard.

[Courtesy Elmer Auld]

They were 100 men on a Flower-class corvette working four-hour watches, 14-16 days at a stretch—as fast as the slowest vessel in a 40-ship convoy could make the crossing, which was usually about 4-5 knots, or 7.5-9.25 kilometres an hour.

They grabbed what shut-eye they could in swinging hammocks, bundling and storing them before each watch, going without showers on one change of clothes, including two pairs of “Nipigon nylons” (heavy wool socks), for the entire trip.

They had one “washing machine”—a five-gallon pail with a toilet plunger.

There was one cook and four toilets, or “heads” in seafaring parlance, for 100 crew. “It’s a good thing we were young,” said Auld. “I’ve showered every day the rest of my life.”

“Red lead and bacon” (tomatoes and cold bacon) and bread so stale it had to be cut with a saw were staples. The quality of the chow generally depended on the sea state, which was often not good in the tiny corvettes that formed the backbone of the convoy defences.

“There’s nothing like waking up early in the morning and seeing them—seven or eight [U-boats] at a distance.”

The 62.5-metre, 950-ton vessels, more suited to near-shore operations than the open ocean, were tossed like corks in even moderate seas hundreds of kilometres from the nearest land. Sea sickness was all but inevitable in the early stages of a voyage; for some, it was chronic.

Collisions between convoy ships, some fatal, were common.

Death was always lurking somewhere beneath the waves. Often the boldest German skippers penetrated the convoys, which could be 15 kilometres across, at least as long, and always excruciatingly slow.

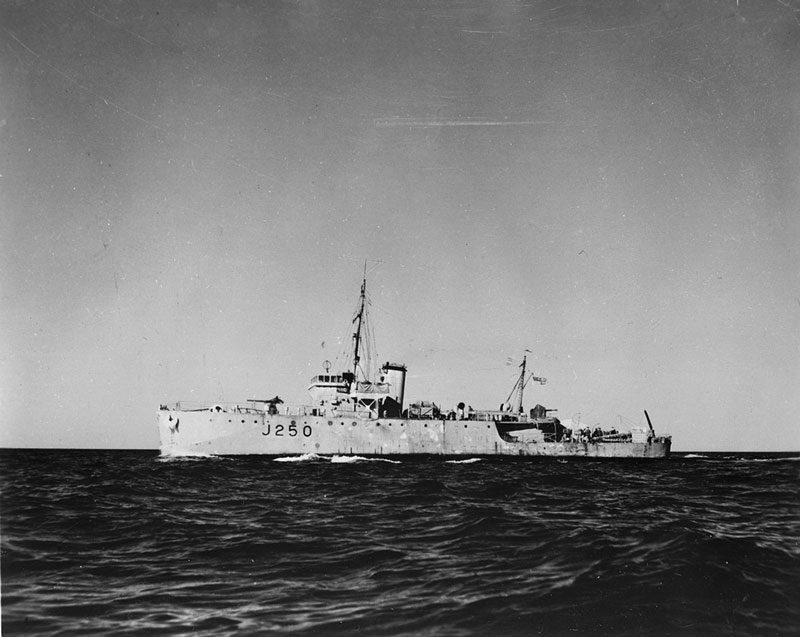

Auld served aboard the minesweeper Burlington on the triangle run between Halifax-Boston/New York-St. John’s, Nfld.

[Government of Canada/canada.ca]

“We’d say, ‘oh there’s going to be trouble tonight.’ And down they’d go. You were scared shitless.”

At the sound of a positive echo, they’d attack with hedgehogs—mortar-style grenades—ahead and depth charges behind. Crew who could, would go topside at the sound of explosions. Auld recalls “quite a few attacks,” but almost no successes.

The submarines’ primary targets were the merchant ships and their cargoes of men and materiel destined for the war effort. They tallied their sinkings by gross register tonnage, a measure of a ship’s carrying capacity, not its weight or displacement.

Fairmile B motor launches conduct wartime patrols off Newfoundland. [Courtesy Elmer Auld]

By war’s end, more than 2,200 Allied merchant vessels—more than 13 million tons of shipping—had been sunk, costing the lives of some 30,000 merchant seamen, over 1,600 of them Canadian.

“They were knocking them off like crazy,” Auld said of the ragtag collection of steamers, transports and tankers that formed most convoys. But HMCS Giffard never did claim a U-boat victim, though Auld thinks they may have been part of an escort group that got one. “They were tough to get.”

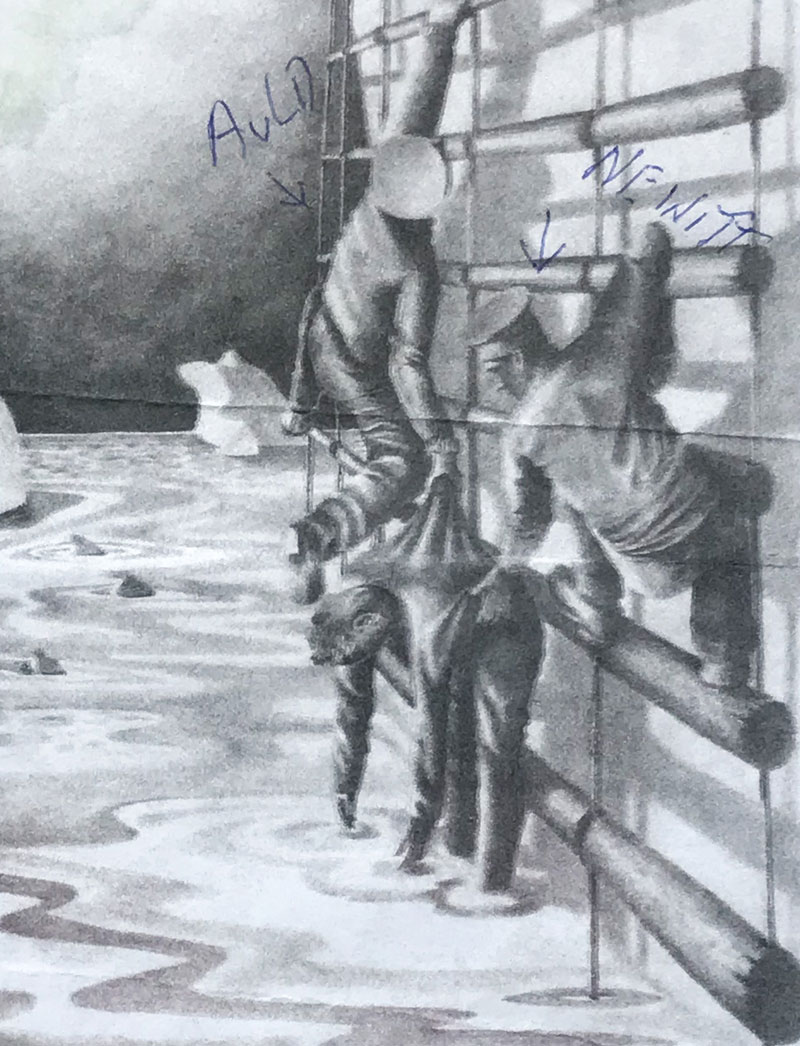

“We were pulling him up and all of a sudden, he slipped out. He was all covered in oil and blood and water, and down he went.”

Auld enlisted in 1941, two months before his 18th birthday, and shipped out to Esquimalt, B.C., for training. His dad was a soldier in the First World War. He’d been gassed and coughed until he died an early death. Elmer Auld wanted none of that. “The navy was popular around here at the time.”

Auld began the seagoing part of his three-and-a-half-year navy career on the East Coast aboard a minesweeper, HMCS Burlington, and spent two months clearing 50 mines the Germans had laid in the approaches to Halifax Harbour.

Life aboard the Flower-class corvette Giffard was damp, cramped and miserable. Auld performed the critical job of ASDIC operator—the vessel’s chief U-boat hunter.[Courtesy Elmer Auld]

He served a couple-of-months’ relief stint aboard a Fairmile B, a speedy motor launch, patrolling the Newfoundland coast before he was deployed to Giffard in 1944.

Auld was aboard Giffard as five ships of escort group C-1 made their way back to St. John’s after convoy duties on May 7, 1944. They were 93 kilometres south of Cape Race, Nfld., sailing on a straight course when Oberleutnant Zur See Erich Krempl aboard U-548 fired two acoustic torpedoes at the trailing ship, HMCS Valleyfield.

One of the underwater missiles, packed with 280 kilos of explosives, hit Valleyfield’s portside boiler room, splitting the ship in two. It sank in less than four minutes, the only River-class frigate lost in the entire war.

Because the ship was the last in line, the others didn’t realize it had been hit for some time. Giffard was the first to reach the scene. Lieutenant-Commander Charles Peterson eased his corvette into the midst of the debris, its engine idling, bow facing the moon to present as little silhouette as possible to the still-present German.

“Rescue was difficult,” Arthur Bishop wrote in Unsung Courage: 20 Stories of Canadian Valour and Sacrifice. “Most of the men were so worn out and numbed from the cold they were unable to help themselves and had to be assisted or carried aboard by Giffard’s crew who went down the scramble nets to fetch them.”

Giffard and HMCS Edmundston, which was working with the rest of the ships in a futile search for their attacker, dispatched sea-boats to help with the rescue.

Auld and fellow ASDIC operator Ross Newitt made their way down the side of Giffard and reached for Valleyfield’s skipper, Lt.-Cmdr. Dermot English. He had tried to climb the scramble net, but was too weak to hold on.

Auld said the skipper’s life jacket wasn’t fastened through the crotch and it slipped off over his head. Auld and Newitt went in the water after him.

“We’re right down in the water about five feet from the edge of the ship,” he recalled. “We were pulling him up and all of a sudden, he slipped out. He was all covered in oil and blood and water, and down he went.

Auld (left) and fellow ASDIC operator Ross Newitt are depicted attempting to save the skipper of HMCS Valleyfield, Lieut.-Cmdr. Dermot English, after his ship was torpedoed and sunk. Covered in oil and blood, English slipped from their grasp and was never seen again.

[Courtesy Elmer Auld]

Just 38 of Valleyfield’s 163 crew survived the attack. Eleven months later, on April 19, 1945, the U.S. destroyer escorts Buckley and Reuben James sank U-548 in a depth charge attack southeast of Halifax. All 58 aboard the sub were killed.

Auld left the navy and for the rest of his days he would appreciate the little things in life—a hot shower, a slice of hot buttered toast, peace.

On Oct. 4, 1944, as Giffard and convoy ONS-33 sailed for Liverpool, England, HMCS Chebogue, another River-class frigate, was torpedoed by Oberleutnant zur See Friedrich Altmeier in U-1227. Seven crew were killed.

“The ass end was blown off of her, but she didn’t sink,” said Auld. A succession of vessels towed the stricken ship into port.

The war ended in May 1945. Auld left the navy and for the rest of his days he would appreciate the little things in life—a hot shower, a slice of hot buttered toast, peace.

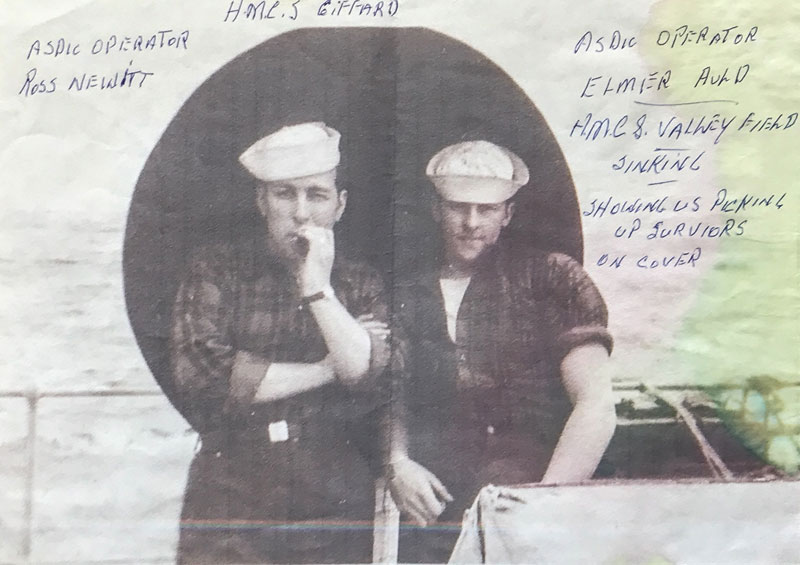

A youthful Newitt (left) and Auld preferred U.S. Navy caps because they had brims to hold onto in the ever-present winds of the North Atlantic.

[Courtesy Elmer Auld]

Nearly 80 years later, the war is rarely far from his thoughts.

“I think about it every day,” he said. “Those were the hell years. We were a lucky bunch. Those 14-16 trips were terrible. I never thought I’d live to be this age.”

Some 294 Flower-class corvettes served with various navies during the war; 33 were lost, 22 of them to U-boats.

—

Order U-boats attack: The Battle of the St. Lawrence, Canvet’s latest volume in its special edition series, Canada’s Ultimate Story. Click here to order it now for home delivery or pick up a copy on newsstands after Aug. 1.

Advertisement