The Easter 1917 success where others had failed marked the first time all four Canadian divisions fought together. Ideas of what the battle was—and wasn’t

—evolved over the ensuing decades.But it wasn’t until 1967 that Brigadier-General Alexander Ross anointed Vimy “the birth of a nation.”

Such declarations moulded Canadians’ perceptions and blurred the lines between the myths and the realities of Vimy Ridge. Speeches, ceremonies and writings tended to reinforce the myths in a country anxious to define its identity.

A nation may not have been born on Vimy Ridge, but Canada did come into its own after the four-day battle. It took on its most significant role of the conflict and earned postwar seats at the Paris Peace Conference and the newly formed League of Nations.

Vimy became, in retrospect, a rite of passage for Canadian soldiers, as well as for war artists of all stripes who trekked to the cratered grounds in the months and years that followed to record their impressions in paint, charcoal and pencil.

Australian captain and celebrated artist William Longstaff painted “The Ghosts of Vimy Ridge” between 1929 and 1931, depicting the spirits of Canadian Corps soldiers on the ridge, having left their earthly battles, and the soaring memorial, behind.

He drew on the words of the monument’s designer, Walter Allward, who said in 1921 that his work had been inspired by a wartime dream in which dead soldiers “rose in masses, filed silently by and entered the fight to aid the living.”

“Without the dead we were helpless. So I have tried to show this in this monument to Canada’s fallen, what we owed them and we will forever owe them.”

A gift to Canada from John Arthur Dewar of the Dewar distillery family, Longstaff’s painting was made while the memorial was still under construction. Except for periods it was on loan, it has hung in Parliament’s Railway Committee Room since February 1932.

Painted by Richard Jack in 1919, “The Taking of Vimy Ridge, Easter Monday 1917” depicts the crew of an 18-pounder field gun firing at German positions as the wounded move past toward the rear. [Richard Jack/CWM/19710261-0160]

The Lens-Arras road along the crest of the embattled ridge is a desolate place as painted by Gyrth Russell in February 1918. [Gyrth Russell/CWM/19710261-0617]

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but Group of Seven artist Frederick Varley told his wife that his art could not say a thousandth of what he saw at Vimy. “We are forever tainted with its abortiveness and its cruel drama,” he wrote to her before painting a burial party at work after the battle in “For What? It is foul and smelly—and heartbreaking. Sometimes I could weep my eyes out when I get despondent.”[Frederick Varley/CWM/19710261-0770]

A Canadian Highlander throws a grenade from the safety of a trench (above right) in a watercolour by Lieutenant Alfred Bastien, one of the more prolific painters of the war.[Alfred Bastien/CWM/19710261-0061 ]

The impressions of the battlefield were still fresh when another Group of Seven artist, A.Y. Jackson, painted “Vimy Ridge from Souchez Valley” in his London studio in 1918. Jackson described his impressionist style, learned in Europe before the war, as “ineffective” for painting conflict.[A.Y.Jackson/CWM/19710261-0171]

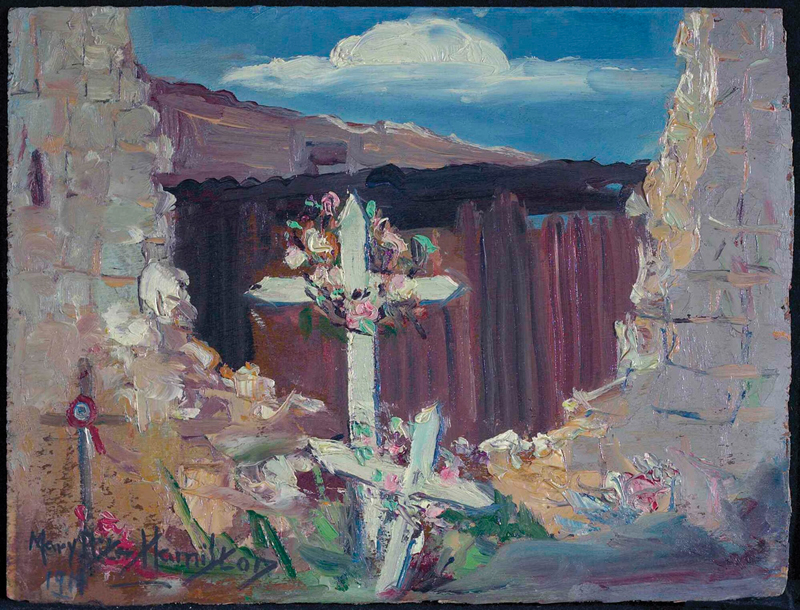

Female war artists were rare but not unheard of. Known by the chronologically inaccurate title of “Canada’s First Woman War Artist,” Mary Riter Hamilton painted the aftermath of the war in France and Belgium, including the reflective “Gun Emplacements, Farbus Wood, Vimy Ridge” (opposite top) in 1919. Elizabeth Southerden Thompson—Lady Butler after marrying up—specialized in paintings of British military campaigns and battles dating from the Crimean and Napoleonic wars. In 1918, she rendered the dramatic watercolour.[Mary Riter Hamilton/LAC/2836031]

Bombers of the 8th Canadian Infantry on Vimy Ridge, 9th April 1917.” Cede Nullis is Latin for “yield to no one.”

[Thompson Butler/LAC/2883480]

Advertisement