How a squadron of war surplus aircraft conquered the tundra and mapped Canada’s Far North

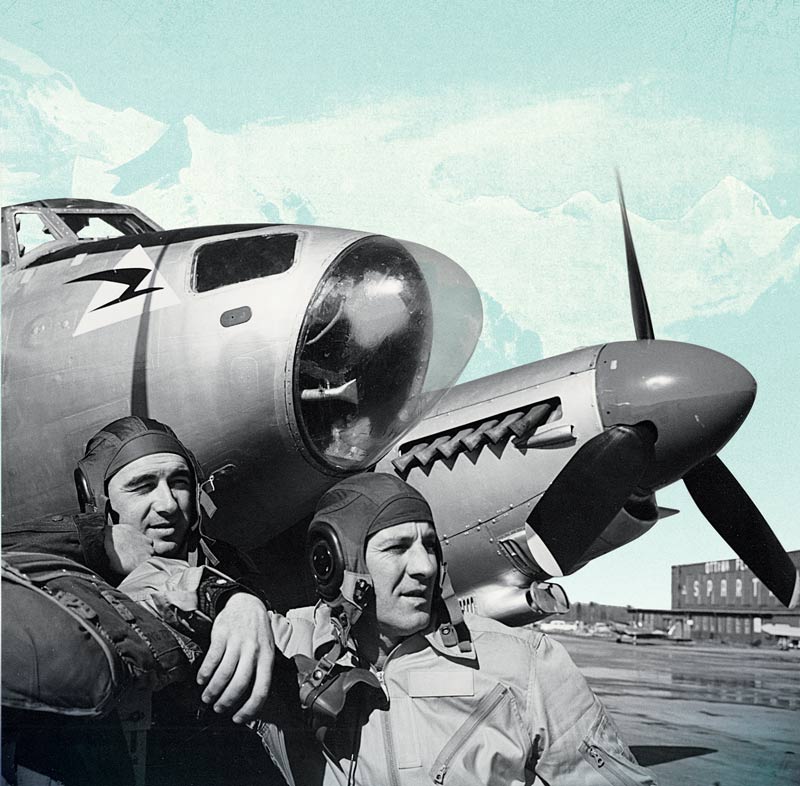

Members of a Spartan air crew at CFB Uplands in Ottawa in 1958. The aircraft is one of Spartan’s de Havilland Mosquitoes, which they relied on heavily in mapping the Far North. [George Hunter via Robert M Stitt]

It was 1946: the war was over, surplus airplanes were going for a song and entrepreneurial spirits were high. Some ambitious veteran pilots and navigators, still adventurous and in their prime, figured the stars were aligned for some kind of flying business.

Over its years, Spartan flew 22 types of aircraft.

Three ex-flight lieutenants—John Roberts, Russell Hall and Joseph Kohut—were accomplished aviators and eventual business partners. Roberts had flown P-51 Mustangs with the Royal Canadian Air Force on photo-reconnaissance out of the U.K. over enemy-held Europe. Hall navigated Wellington bombers based in Egypt and the Bahamas. Pathfinder navigator Kohut earned a Distinguished Flying Cross in 1943. The trio met toward the war’s end while serving at RCAF Station Rockcliffe, where they flew photo-mapping missions.

An aerial survey business seemed natural. With a borrowed $10,000—more than enough to snag several war surplus Anson airplanes at $250 apiece—they formed Spartan Air Services Ltd. in 1946 and set to work.

Initial operations were air surveys, some for the federal government. The fleet soon grew with more Ansons, Venturas, Cansos, Dakotas, Yorks, Lancasters—a vast choice of ex-warbirds were on the market. Over its years, Spartan flew 22 types of aircraft.

The Ansons soon needed to be replaced, as newer cameras and map-making technologies required craft that could fly higher. For the federal government, that meant runs at nearly 5,000 metres. And before long, much higher.

In 1947, Ottawa announced plans to map the entire country—all 10.1 million square kilometres of it. For standard 1:50,000 scale maps, flying above 10,000 metres was in order. Eager to get in on the action, Spartan purchased eight P-38 Lightnings. Its high-altitude reconnaissance version had an impeccable reputation; it was credited with over 80 per cent of all air reconnaissance photos taken by U.S. forces during the war. And at more than 600 kilometres per hour, it could map a lot of ground in each trip.

The RCAF handled most of the federal mapping at first. But the demands of the Korean War forced it to drop the air survey role, leaving the field open to the few civilian operators capable of tackling it. Never was there a better chance for Spartan, ready with a fleet of newly modified P-38s. “The Korean War made Spartan,” said vice-president Hall.

Despite early promise, however, the P-38s fell short. They were fast and flew high, but their three-hour maximum endurance limited their ability to map lines over vast Arctic distances. There was also limited space on board for larger cameras, such as the Wild Heerbrugg RC-8.

Enter the Mosquito. Conceived as a light bomber and introduced during the Second World War, the de Havilland Mosquito was designed to rely on its 640 km/h speed rather than guns for defence. Its near seven-hour endurance beat the P-38 hands down. A bargain at $1,500 a pop, Spartan went to England and bought 15.

Retrofitted to add a third crew station in the fuselage for the cameraman—featuring a larger camera, an extra fuel tank and an access hatch—the Mosquitoes were ready for action.

In early summer 1954, with a rich federal government contract in hand, Spartan set out to find suitable northern bases of operations. A weeks-long search of the challenging landscape located a site at Pelly Lake, roughly 1,000 kilometres northwest of Churchill, Man., in today’s Nunavut. Supplies were delivered by float plane, starting with a cook, food, tents and gallons of that northern essential, mosquito dope. Within 45 days they were fully operational with a 1,524-metre airstrip, fuel, oxygen, long-distance very high frequency radio and even a darkroom. And when crews had time, the fishing was fantastic.

For many of the operations farther north, Spartan also flew out of Cambridge Bay on Victoria Island, Shepherd Bay and Mould Bay on Prince Patrick Island, Resolute Bay on Cornwallis Island and Coral Harbour on Southampton Island. High-frequency radio links connected them. Logistics soon became a major challenge; everything had to be pre-positioned by barge, sealift or air. As a result, with its railway and marine connections, Churchill became an important staging and maintenance base.

More than radio links were needed for map accuracy due to the distances involved, so several short-range radar navigation stations were set up throughout the North in summer, manned largely by university students on summer jobs. They provided critical weather reports for the pilots.

Aerial cameras, such as the Wild Heerbrugg RC-8, were big, clunky and instrumental in mapping the Canadian North. [Calgary Mosquito Aircraft Society]

Long before navigational luxuries such as GPS, flying mapping lines was tiring, demanding and monotonous. Each new line meant starting the camera roughly 15 to 30 kilometres back to make sure the operator could adjust for drift and interval time for the new heading and ground speed. Once on the line, the pilot had to maintain altitude within 61 metres and heading precisely within two degrees for hours—all with no autopilot or co-pilot. The Mosquito cockpit was noisy, cold and unpressurized, and the work required intense concentration and co-ordination by the three-man crew. The navigator lay prone in the plexiglass nose section during runs.

Measurement of drift off-line was critical. But that’s a hard thing to do without a map. Spartan navigator Bob Bolivar had the answer.

“Joe Kohut invented an ingenious device they called a drift sight which was mounted on a bar in front of the navigator,” Bolivar said. “It was designed so that you could get drift and also look and project three lines over each side of the airplane.

“You’d pick a line, go down it as best you could and then with this drift sight you could sketch in the adjacent lines [of] a lake or anything prominent. Then when you came back [and] turned around, you’d go down that line. You’d have a sketch of that line and that’s what you’d navigate with. You also sketched a second line over and then, when you turned around and came down the line you’d already sketched, you’d fill in the detail as you went. And you just keep doing that, paralleling the lines.”

Magnetic compasses are useless so far north, so “we would set the electric gyro to zero when we were working on-line. Zero would be the pilot’s heading,” said Bolivar. “Once we got off the line to find our way around, I would check our heading on the astrocompass and that’s how we would navigate.”

An astrocompass determines true north using star positions and local time. Flying east-west presented tricky new challenges for the navigator: lines of longitude converge increasingly toward the North Pole.

“With a real clear day you could run on-line for 250 miles no problem,” said Bolivar. “A good day could produce 1,000-plus miles of useable photography per sortie. You needed a good pilot who could maintain heading accurately.”

Hour upon hour at almost 11,000 metres on pressure breathing took its physical toll too, similar to the bends. “We would use 100 per cent oxygen as soon as we got into the airplane and stay on it until we landed again.”

The cameraman fared no better. His compartment was cramped, claustrophobic and isolated with only a simple intercom to communicate with the pilot. Conversation had to be maintained every few minutes to confirm all was going smoothly, as an oxygen system failure could mean unconsciousness and death in a matter of minutes.

“The safest thing was to fly—I had no other option.”

The flying had its share of incidents. In July 1956, pilot Al MacNutt took off from Pelly Lake in a Spartan Mosquito for what was expected to be a routine survey run 480 kilometres to the west. Three hours later, his port engine oil pressure started fluctuating. He reduced power and feathered the prop (increasing the blade pitch on the variable-pitch propeller to reduce drag). Suddenly the aircraft lurched violently 90 degrees to port and the prop rapidly over-sped, causing an engine fire.

MacNutt ordered the crew to bail out—cameraman first, as his access was through a bottom hatch and he’d be trapped if they had to belly-land. The cameraman went, followed by the navigator. MacNutt then prepared to bail but when he unhanded the controls the Mosquito flipped, inverted and quickly lost 1,500 metres.

“The safest thing was to fly—I had no other option,” he later said. Still far from base with no navigator or maps, he skillfully limped back for a belly landing, leaping free just before the aircraft exploded in flames.

“There were a lot of fatalities on the Mosquito,” said Bolivar, who amassed nearly 1,300 hours on it. “It was a challenging aircraft—the pilot couldn’t make many mistakes.”

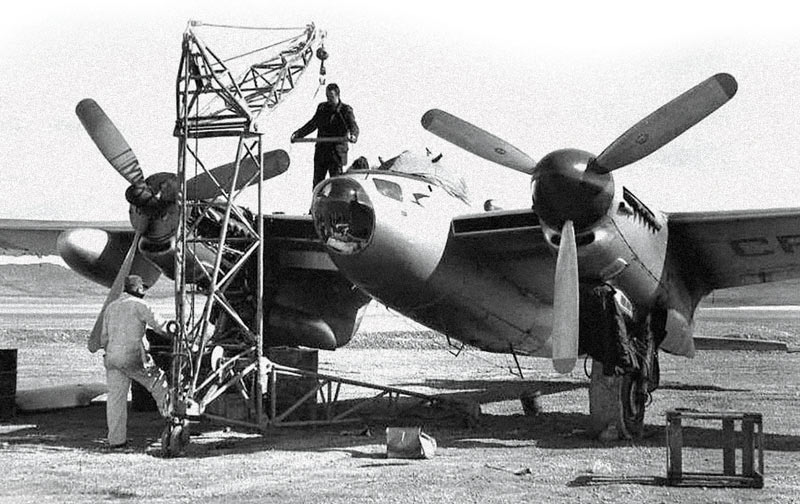

CF-HMS on a fuel stop in Yellowknife. Spartan prized their Mosquitoes due to the aircraft’s seven-hour endurance. [Wikimedia]

Summer fog was a frequent problem, grounding planes for days. Sometimes when clear locally, boredom was relieved by taking “test flights” where crews would stage mock dogfights for entertainment. But they were ready when conditions cleared in their survey area.

Operating seasons in the Arctic were short. To ensure map-worthy topographic detail, they couldn’t start much before early July when snows had melted. But the long daylight hours allowed many 16-hour flying days. In good weather each aircraft could handily manage two six-hour sorties daily.

By fall, days quickly shortened and temperatures dropped. Crews and aircraft would deploy south for other work to maintain cash flows, usually in warmer climes such as Kenya, Colombia, Argentina and the Dominican Republic.

September 1957 brought welcome news as summer operations slowed: Spartan’s contract for the following year was extended to within 800 kilometres of the North Pole. For $2.8 million, it covered 571,800 square kilometres of the Arctic Archipelago. Spartan’s share was the western half of the islands.

By 1958, Spartan could boast more than 60 aircraft and 400 employees. But the Arctic islands contract was largely complete by 1960, with just a few areas needing re-flying. Canada’s largest-ever mapping survey was nearing its end.

Overseas work continued, though it lacked the intensity of those Arctic years. The last operation flown by a Spartan-owned Mosquito was in November 1964 in Argentina, ending in an ignominious farewell: crash-landing at Las Higueras Airport in Rio Cuarto and written off.

The maps generated from their thousands of air photos remain in use today. CF-HMS, one of the last remaining Spartan Mosquitoes, is currently under restoration at the Bomber Command Museum of Canada in Nanton, Alta.

Advertisement