A camp identity tag was among the items uncovered by the excavation.

[ Danielk Frymark/Central Museum of Prisoners of War]

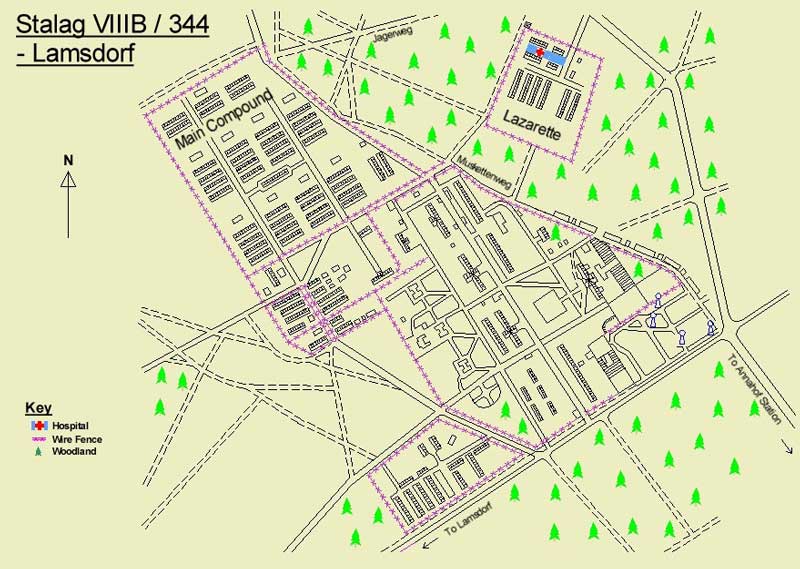

The dig was conducted in an overgrown area of what was once the Lamsdorf PoW camp—specifically, the principal subcamp of Stalag VIII known as Stalag VIIIB in what is now Łambinowice, Poland. The archeologists uncovered syringes, a razor fragment, underwear and uniform buttons, utensils and remnants of a heating stove.

“It was a part of the camp that had never before been the subject of field research,” said the project’s head, Dawid Kobiałka of the University of Łódź Institute of Archaeology in central Poland.

“Even the precise location of its individual buildings and their present state of preservation was unknown.”

The camp was established during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, when it held some 3,000 French PoWs. It expanded during the First World War, taking in more than 90,000 prisoners of various nationalities.It was revived at the outset of the Second World War, initially to hold Polish PoWs but, by war’s end six years later, as many as 400,000 Allied prisoners from almost 50 countries had passed through the various stalags of Lamsdorf. Between 10,000 and 20,000 would be housed at a time in VIIIB—renamed Stalag 344 during a 1943 camp reorganization. They included Canadians, Americans, Britons, Soviets, Australians and Kiwis.

In addition, there were more than 700 subsidiary arbeitskommandos, or work parties, comprised of lower ranks toiling away in coal mines, quarries, factories and on railroads across present-day southern Poland and northern Czechia, or Czech Republic.

“You will be able to guess why so many of you will have not yet had a visit,” Chaplain John Berry wrote in the February 1943 issue of the camp magazine, The Clarion.

Non-commissioned officers and other enlisted Canadians captured during the disastrous August 1942 raid on Dieppe, France, were taken to Lamsdorf by rail, in cattle and boxcars. When German Red Cross workers tried to feed them at a railway station, the guards knocked the food from their hands.When captive troops arrived at their destination eight to 10 days after the raid, they were in rough shape. Some were wounded; others had been beaten; all were wracked by hunger and thirst.

“These people just fell out—absolutely whacked,” said a British medical officer who witnessed the event. “Covered in excreta and in a terrible state.

“They’d been in there for days. Things we’d read about, and impossible to describe—the stench, the horror, the tragedy of it all.”

They were welcomed by the camp commandant, whose standard address, delivered via interpreter, went something like this: “For you the war is over. Germany’s enemies will soon sue for peace. Prisoners should be patient, as they will soon be sent home.”

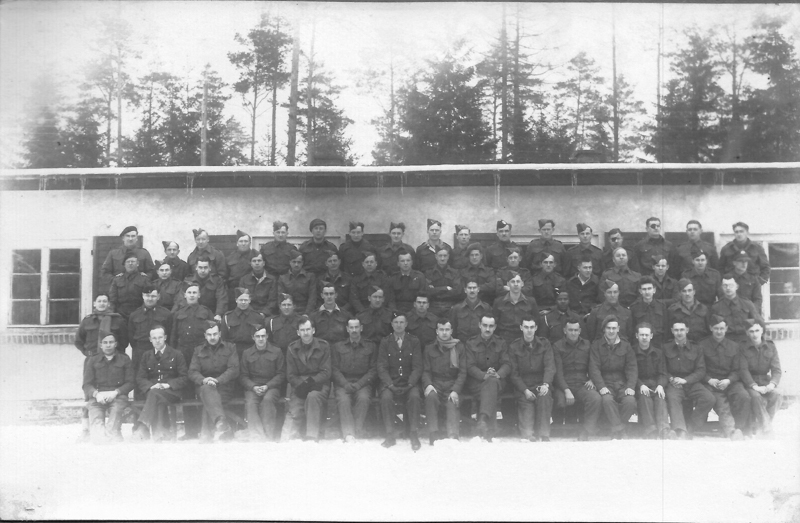

Stalag VIIIB prisoners pose for a picture. This group made the forced march near the end of the war and were rescued by American troops. Some spent months in hospital due to malnutrition. [Wikimedia]

No one moved, recalled Sergeant Hubert Brooks of Montreal, a Wellington navigator/bomb aimer who was taken prisoner after his plane was shot down during an April 1942 raid on Hamburg.

Others, who’d been living on meagre prison camp rations, were simply worked to death, died of their wounds, or got sick and perished.

In his paper “On the Beach and in the Bag: The Fate of Dieppe Casualties Left Behind,” Charles G. Roland of McMaster University in Hamilton said that in at least one respect the Dieppe PoWs were fortunate to have been captured in 1942.

“By the middle of this year, the general level of health of PoWs in German and Italian hands reached its highest point in the entire war.”

So, while some wounded Canadians were summarily executed on the beach at Dieppe, others saw some of the best hospital facilities of the German PoW camps when at Stalag VIIIB. The lazarett, or military hospital, was made up of 11 concrete buildings.

Six were self-contained wards, each with a capacity of about 100 patients. The others served as treatment blocks with operating theatres, X-ray and laboratory facilities, as well as kitchens, a morgue and accommodations for the medical staff.

The complex was headed by a German officer with the title oberst arzt, or colonel doctor, but the staff was comprised entirely of prisoners, including general practitioners and surgeons, even a neurosurgeon, psychiatrist, anesthesiologist and radiologist. Many of the orderlies, working in three-month stints to avoid prolonged exposure to tuberculosis, were well-trained and experienced.

Many of the wounded from Dieppe ended up here and, though supplies were chronically scarce, they often received better care than expected even from a conventional hospital.

“We were on duty 24 hours a day, you see,” former orderly Frederick Hesk told Roland. “You were there on call all the time. Which didn’t matter because there was nothing else to do.

“But it meant that people got quick treatment whereas, even in an ordinary hospital, they might have had to wait a while till a night sister came around.”

Sergeant Albert Willis displays his manacled hands in a smuggled photograph taken by fellow PoW William Lawrence. The hands of prisoners at Stalag VIIIB were bound every day for 14 months from morning parade until evening parade as a German reprisal for alleged Allied mistreatment of German prisoners during the Dieppe raid. Cord was used until manacles arrived.

[Bill Lawrence/PoWMuseum]

Others, who had been living on meagre prison camp rations, were simply worked to death, died of their wounds, or got sick and perished.

Some were killed in air raids, including a series of attacks by American bombers beginning in June 1944. Some 30 British PoWs were killed in and airstrike on a work crew in December 1944.

“We were not allowed to go into the air raid shelters, which among other things we had been forced to build,” recalled British tanker Eric Reeves, who was captured in April 1940 and escaped in early 1944.

“The other nationalities there were also hard hit.”

Polish commander, Czesław Gęborski, was dismissed and investigated on claims he set fire to a barracks and ordered guards to shoot inmates trying to put out the flames.

An overhead image shows the site of the former camp hospital at Stalag VIIIB where archeologists are now working.

[Danielk Frymark/Central Museum of Prisoners of War]

The lucky ones got far enough to the west to be liberated by the U.S. army. The unlucky ones, who didn’t die, were liberated by the Soviets, who reached Lamsdorf on March 15, 1945. Instead of quickly turning them over to their western Allies, the Red Army troops held them as virtual hostages for months.

Many of the Lamsdorf PoWs were finally repatriated in late-1945 through the port of Odessa on the Black Sea.

At war’s end, the camp was used by the Soviet-installed Polish Ministry of Public Security to house 8,000-9,000 Germans, both PoWs and civilians.

Polish army personnel repatriating from PoW camps were also processed through Lamsdorf and sometimes held there for months. Some were later released; others were sent to gulags in Siberia.

About 1,000-1,500 German prisoners died in the camp from malnutrition, lack of medicine and acts of violence and terror by the guards. In October 1945, the transition camp’s Polish commander, Czesław Gęborski, was dismissed and investigated on claims he set fire to a barracks and ordered guards to shoot inmates trying to put out the flames. Some 48 prisoners died.

By 1947, however, the investigation was dropped without charges and Gęborski was promoted to captain. In 1956, during the so-called Khrushchev Thaw following the end of Stalinism in Poland, the investigation was resumed and Gęborski was arrested. A court eventually declared him not guilty. After communist rule ended in Poland in the 1990s, he was tried again, only to have the case abandoned in 2005 due to the poor health of many involved, including Gęborski.

Today’s remnants of the Lamsdorf camp are largely enshrouded in lush forest. Archeologists searching for the hospital barracks in August removed a few centimetres of forest undergrowth, revealing a concrete floor, 63×15 metres.

They found the base of a tiled stove and fragments of clay stove tiles, some with floral motifs and maker’s marks.

They’ve also made 3D models of the soil around the camp to help identify possible mass grave sites. Most of the dead are known to be buried in a local cemetery and mass graves in the nearby village of Klucznik.

The team is returning to the site this month and again in summer 2023 for more research.

Advertisement