“Sometimes it’s going to be a smell. Sometimes it’s going to be a sound,” says Hélène LeScelleur. “And then it reminds me of the horror that we’ve been through.”

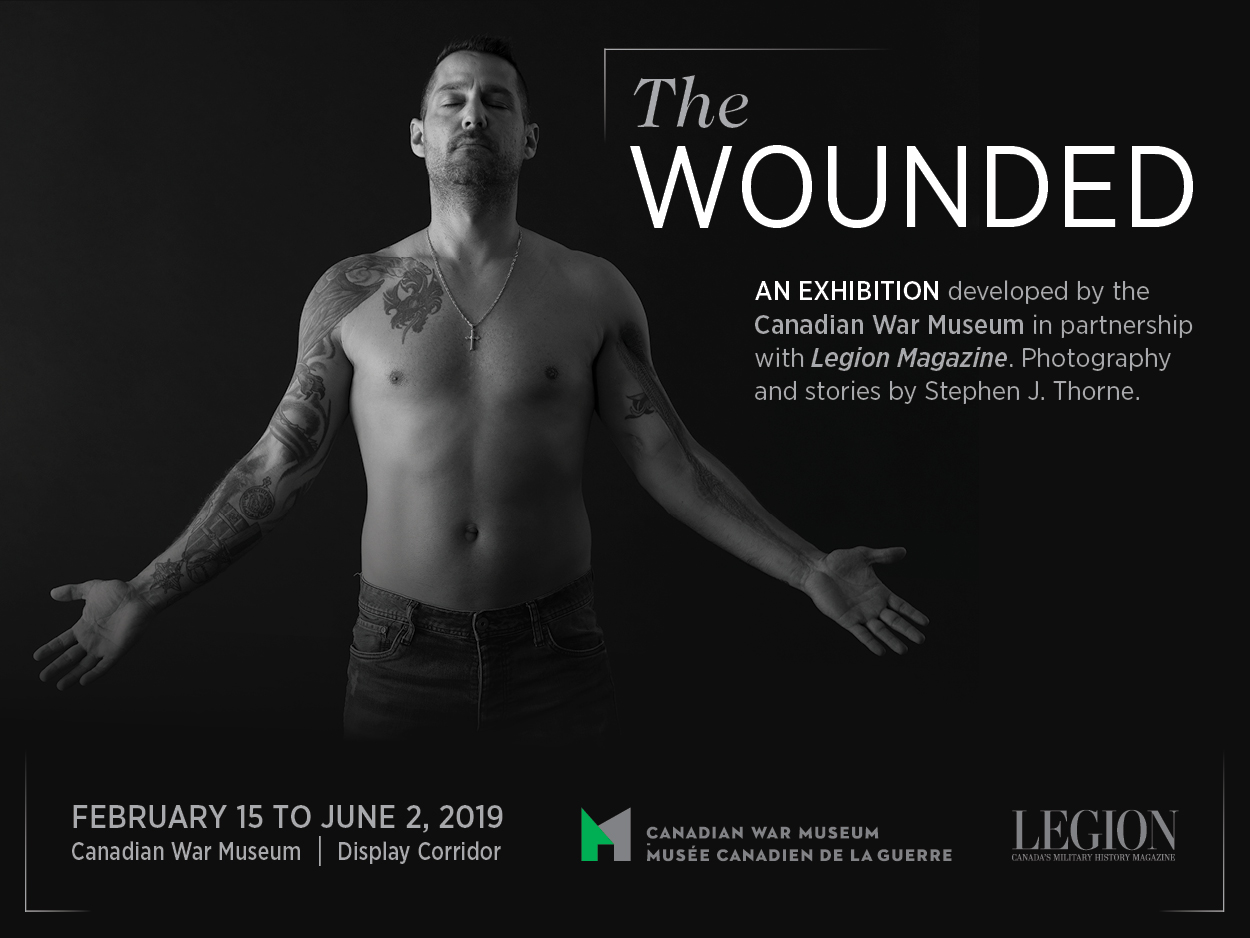

Story and photography by Stephen J. Thorne

“Seeing people decapitated, it’s not that usual for anyone,” says former army medic Hélène LeScelleur. “I saw a lot.”

It wasn’t an image she had contemplated when she signed up for the militia and fell in love with the military.

LeScelleur had challenged authority her entire youth, so when military brass told the newly minted lieutenant and by then 12-year army veteran that she was “too junior” to carry out her duties in Afghanistan, she went on the offensive.

A Bosnia veteran with aspirations for more, the former master corporal and administrative clerk had returned to school and completed a program in health-care management. She joined a medical unit in Valcartier, Que., and in less than a year was promoted to lieutenant.

She was made deputy commander of the medical company of 5 Field Ambulance, then her unit was pegged for deployment to the war zone. As their preparations ramped up, however, LeScelleur was told she’d be replaced with a longer-serving officer.

“I got really, really mad,” she said. “I went to see the CO; I slammed my fist on his desk and I said ‘there’s no way you’re going to take my troops overseas without me.’ He said ‘you’re too junior.’”

LeScelleur, who as a teen activist had led rallies, skipped classes and railed against authority, had sought out the military life as way of channelling her energies and adopting a more structured, disciplined way of being.

It had worked. She’d found her calling, and she wasn’t going to let someone else’s limited concepts of experience and seniority keep her from fulfilling her destiny.

“I’m not too junior,” she told her superior in no uncertain terms. “I might be junior in rank but on paper I have more expertise and practical experience than the person you would like to bring. There’s no way.”

And in a soliloquy worthy of a Jedi warrior invoking the powers of the Force, she told him: “You will promote me acting captain and you will give me my job back.”

And so he did.

It was 2007, and the rebel from suburban Montreal could not have anticipated what was in store for her, the consequences of the orders she gave or the difficult decisions she would have to make with 85 people under her deputy command.

The decisions started before she ever left Canada, and the consequences became evident not long after they arrived in Kandahar.

The company trained in Texas and Wainwright, Alta., and Master Warrant Officer Mario Mercier emerged as her star.

At a time when the medical corps was reclaiming respect and status within the military, she considered him the best of his breed—a veteran NCO who knew his job and stood up to members of the combat arms whose regard for the medicos had eroded in the dark years that followed their life-saving exploits in two world wars and Korea. For years, they had been largely relegated to standby duty at exercises and ranges. All that would change in Afghanistan.

Another of her stars was Master Corporal Christian Duchesne, a widely respected medic they called “Conan” who ran into complications three weeks before they were to be deployed. It didn’t appear he would be able to go, until LeScelleur went to bat for him and convinced authorities that he was vital to the mission.

Twenty-two days after they arrived in Afghanistan, on Aug. 22, 2007, Mercier, 43, and Duchesne, 34, were killed along with an Afghan interpreter when their light-armoured vehicle was taken out by a roadside bomb during a major operation. Several others were wounded, including a television cameraman who lost a leg.

As second-in-command, it was LeScelleur’s job to supervise medical evacuations from the battlefront to the hospital at Kandahar airfield. “I was always the one confirming who was dead or injured, so I was always the first one to know.”

Many colleagues were at the scene when Mercier and Duchesne were killed. For LeScelleur, it was an especially difficult way to start a tough job. “I felt so responsible because I pushed so hard for him [Duchesne] to come.”

“A lot of my medics were affected,” she said. “It was a shock and one of my biggest challenges. It was really, really, really hard. Everybody was crying. It was a hard page to turn, but we had to because the war was not over.”

Thus began a cycle of coping with losses that couldn’t be processed, “because the day after, another one is injured and the day after that, another one is dead.”

LeScelleur spent as much time outside the wire as in. Besides conducting military medical operations, she started free clinics for Afghans in the region around Kandahar, collecting data and information for Afghanistan’s public health ministry in the process. The program was a huge success.

___

One night, she was in a group of vehicles headed back to base after a long day of briefings at various locations in preparation for the Canadians’ next big operation. It was 10 p.m. The eight soldiers in her LAV-3 were the last in the convoy.

LeScelleur was tired. Even with the bumpy ride and the hard bench she was sitting on, she was drifting off to sleep. Suddenly they were hit by a remotely detonated improvised explosive device (IED).

“I remember the shock,” she said. “If I close my eyes, I can still feel the blast coming through me. And I remember opening my eyes. I was upside down.”

The vehicle was still intact but she thought the others around her were dead because nobody was moving.

“The officer of the vehicle was screaming ‘Medic! Medic! Medic!’ We didn’t know if the driver was alive because the hatch was down.”

As LeScelleur tried to extricate herself from the vehicle, the crew commander was warning of a possible attack. It was a dark night, no moon. They could see flashlights.

“I went to the hatch and when I opened it the guy looked at me; he was full of blood.”

He assured her he was fine except for a large cut on his forehead. She helped him out of the hatchway and they put everyone in the back of the vehicle.

“We didn’t have any communication and we were cut off from the rest of the convoy.”

About 50 metres of roadway had been completely destroyed. Their 17-tonne LAV-3 had been pitched backward. Four of eight tires were gone. A forward observer who had been sitting next to LeScelleur had a working portable radio.

“We were lucky because nobody was badly injured. One guy broke his leg. But all of us, it was minor injuries. I got my sacrum fractured, same as the crew commander, same as the guy sitting next to me.”

Still, the adrenaline-charged medic later managed to carry a six-foot-tall soldier 200 metres to safety and stood guard outside the toppled vehicle for four hours—without night-vision goggles—waiting for an attack that never came.

“That night,” she says, “I was not afraid to die.”

At one point, she saw movement in the darkness. She cocked her weapon and took aim when suddenly the movement came straight at her. She froze and didn’t fire. It was a dog, and it ran past her. Later, she surmised that it may have been dispatched to draw fire in order to determine her position in the darkness.

Eventually they were rescued, returning to the forward operating base they’d last left. It was 2 a.m. The next morning, they were returned to Kandahar by vehicle.

“At that point, I didn’t realize that I was scared,” she said. “After the mission, I realized that I was really afraid to die that night. You don’t normally say that to yourself when you’re a military person.”

Months later, by the time she reached their decompression point in Cyprus where they spent five days before heading home, LeScelleur knew something was wrong.

“I was no longer capable of crying. And I started to feel like I was choking all the time because I was not capable of breathing like I was supposed to breathe.”

They would go to briefings in the morning, then drink in the afternoon until they passed out. The briefings, she said, were ineffectual. They didn’t address the specific experiences the Canadians had endured.

“It was like two worlds trying to mix in one and it wasn’t working. Everybody was just going crazy—aggressive, drinking, trying to erase everything they saw and at the same time let go of everything before they went back home.

“So instead of hitting your wife or being stupid and doing something crazy, it was like a place to just let everything explode. It was really bad.”

The feeling that something was wrong grew the closer she got to home. When they arrived, the troops went their separate ways to be with family and friends.

“You don’t necessarily talk about what happened to anyone. And when I got back to work, instead of being with my troop and doing a sort of slow dissolution of the group, I was already put in another position as adjutant of the 5 Field Ambulance.”

She was promoted from acting captain to full captain; all the unit’s administrative work would go through her. The job was intense and the pressure was high.

At one point, LeScelleur was supposed to accompany her commanding officer to a dinner with families mourning the losses of their loved ones in Afghanistan. She couldn’t do it. “I was not capable of coping with the loss. I felt so responsible.”

“I had my first panic attack in my office,” she said. “I was crying and no longer capable of thinking straight.”

She went to her commanding officer and told him she couldn’t accompany him that night. “I’m done,” she told him. “I need to go see someone; I’m not well at all.”

He sent her to the base hospital, where her CO from Afghanistan took her into his office. “I was crying, screaming, shaking, everything.”

There were eight soldiers in LeScelleur’s vehicle that night. All eight suffered post-traumatic stress injury and one, the driver, committed suicide.

The doctor put someone in charge of LeScelleur’s case and she began psychotherapy with an outside contractor. Shortly after, the office of then-governor general Michaëlle Jean called. They wanted her to be the governor general’s aide-de-camp after she had been nominated by her peers in the battle group.

“In my mind, being an aide-de-camp was a way of leaving Afghanistan behind. It was kind of a way of escaping what was triggering me. It didn’t last long. I had to go to CFB Trenton for a ramp ceremony and it took me back exactly where I was when I was in CFB Valcartier.”

She started drinking. She tried to commit suicide. After 15 months, she asked Jean if she would let her leave so she could get help.

“Because she was a former social worker, she knew exactly what I was going through and she said she was surprised I’d toughed it out that long. She gave me a super letter for the work that I did.”

___

Not so back in the military. She said she was treated like “the baddest person.”

“I got told I was the rising star and then I was the black sheep of the health-services trade. For them, even if I was not well, it was something that you did not do, leaving a high-profile position. So, I was put on a shelf somewhere in the health-services headquarters. And everything unfolded from there.”

Today, it’s not the image of headless soldiers that triggers her. “Sometimes it’s going to be a smell. Sometimes it’s going to be a sound. And then it reminds me of the horror that we’ve been through.”

Recently married and a doctoral student in social work at the University of Ottawa, LeScelleur is a different person than she was when she set out for Afghanistan, or even from who she was when she came back.

She hopes to improve services for veterans struggling with psychological trauma.

The military dissolved her team too fast, she says. Soldiers who share experiences in war zones and other high-stress areas should be given time together after they return to their jobs back home to “try to make sense of what happened.”

“These missions in Afghanistan were certainly not the same as what they’ve done in the past or what they’re doing right now in different areas. When people go to war, you cannot just [dissolve] teams and think that people are going to be OK.”

There also has to be a better recognition of what they’ve been through. She says recent changes to transition services for outgoing veterans are a good sign.

“But being forced out of the military because of an injury you sustained while doing what they asked you to do, it’s really hard to deal with,” she said.

“Being able to stay, being able to accommodate people—that should have been the way of doing things instead of kicking people out. We see people with prostheses being deployed. But because it’s psychological, they’re scared to say ‘we’re going to leave you with a gun.’”

Medication, she says, is the same as a prosthesis. It enables sufferers “to be stable in their new reality of life.”

LeScelleur hopes the military’s new departure protocol works better than the old one. She said the way she was escorted out of the military in April 2016 after 26 years of service was “almost like a dishonour.”

“The last day, when I returned my kit, it was like every portion of yourself that you are putting on the table,” she said, explaining that the difficulty and the insult was made worse by the fact that some of it was thrown away right before her eyes.

“The last person I saw on my last day of service was a civilian who took not even five minutes with me. She said ‘sign here; sign here,’ and I said ‘that’s it?” She said ‘yeah.’ Not even a ‘good luck’ or a ‘thank you.’ And then I had to return my identity card, and I had to be escorted back to the front door. It was like the last piece of me was gone and I could no longer be trusted. I cried so much afterward.

“I’m not saying that we need necessarily big parades and things like that. Just a minimum of sympathy will do.”

___

The Canadian War Museum and Legion Magazine are collaborating on a new exhibition featuring haunting portraits of wounded veterans by writer-photographer Stephen J. Thorne.

Advertisement