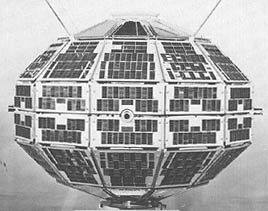

The Canadian Alouette I satellite. [Wikimedia]

Alouette I “was one of the most successful scientific satellites ever,” wrote Jack Rigley, vice-president of the Satellite Communications Research Branch at Communications Research Centre Canada.

Equipped with an ionospheric sounder and roll-up antennas, the satellite achieved many feats of its time, including having the longest battery life, supplying the greatest amount of scientific data and bringing scientific co-operation to the Cold War-era space race.

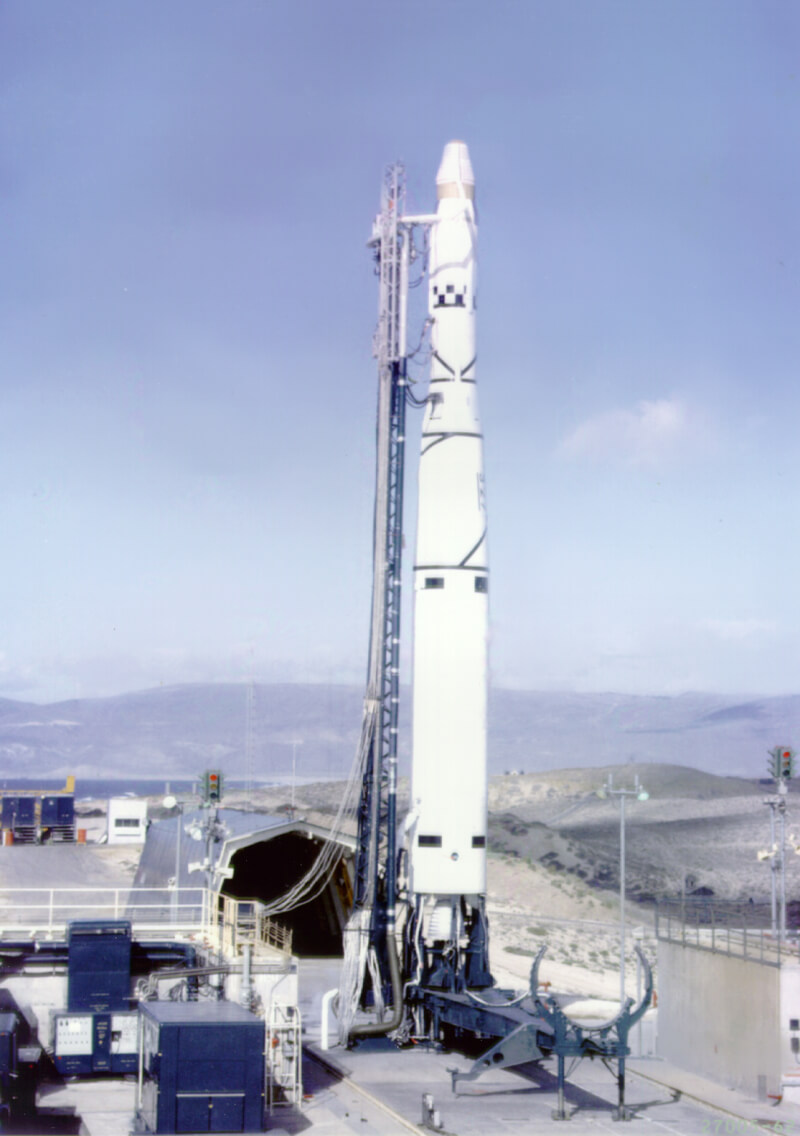

Thor Agena B, the same rocket that launched Alouette I into orbit. [Wikimedia]

Canada set its sights on creating a more integrated world by improving shortwave radio transmissions.

As tensions between the Soviet Union and the U.S. reached new heights and scientists on both sides became isolated from each other, Canada hoped to bridge the gap.

“Canada was motivated by the astute insight that satellites could play a critical role in linking together and developing a vast and sparsely populated country,” acknowledged a 2012 government review of the project.

Inspired by the scientific spirit of the 1957-58 International Geophysical Year, a global research initiative meant to propagate environmental study, along with a U.S. call for international collaboration in aerospace advancement, Canada set its sights on creating a more integrated world by improving shortwave radio transmissions, an important method of communication at the time.

Shortwave radio, however, was reliant on the ionosphere, a part of Earth’s upper atmosphere that reflects radio waves back to the planet, which proved to be highly irregular in northern latitudes, making radio communication in remote regions difficult.

So, following the individual launches of American and Soviet satellites, Canada proposed the creation of its own, which was meant to collect and transmit data of the ionosphere for one year and stay in orbit for another three to five centuries as Canada’s own celestial trophy. By April 1959, Canada signed a deal with NASA to use its launching services.

Led by Canadian physicist John Chapman, the Defence Research Telecommunications Establishment quickly got to work, aspiring to create a cutting-edge satellite that would run on a new type of solar-cell technology. A highly sophisticated piece of machinery, even the dream-makers at NASA thought Canadian expectations for Alouette I were too high.

“The spacecraft was complex and exceptionally advanced for the technology of the time,” Colin Franklin, the chief electrical engineer for Alouette I, told The National Post.

“In fact NASA considered it too advanced for the available technology.”

Skeptics were quick to point out the launch’s improbability and the amount of funding “wasted” on such an initiative.

NASA’s reservations about Alouette I weren’t entirely unjustified given the young age of the project’s research and design team, along with the fact that Canada had to create a satellite program from scratch. And outside of NASA, skeptics were quick to point out the launch’s improbability and the amount of funding “wasted” on such an initiative.

“I remember somebody sarcastically commenting that we were the farm team,” said Franklin.

Regardless, it only took three and a half years to complete Alouette I. On a late-September evening, the 145-kilogram Canadian tech defied the odds, not only successfully launching from California’s Vandenberg Air Force Base, but remaining active for a decade at a time when satellite batteries were notoriously short-lasting.

“The success of Alouette gave Canada an international reputation for excellence in design engineering,” Franklin stated. “And in particular it gave de Havilland of Toronto, which later became Spar Aerospace, the credibility to bid on the Canadarm.”

But Alouette I did more than just make Canada a hotbed of aerospace ingenuity; the satellite also brought countries together in an era when nuclear-war paranoia and political propaganda reigned supreme.

“The [Alouette] program, which started as a joint effort between Canada and the United States,” said Rigley, “grew steadily to include a total of 10 nations.

“It was the cornerstone on which Canada became a leader in the peaceful uses of space.”

Advertisement