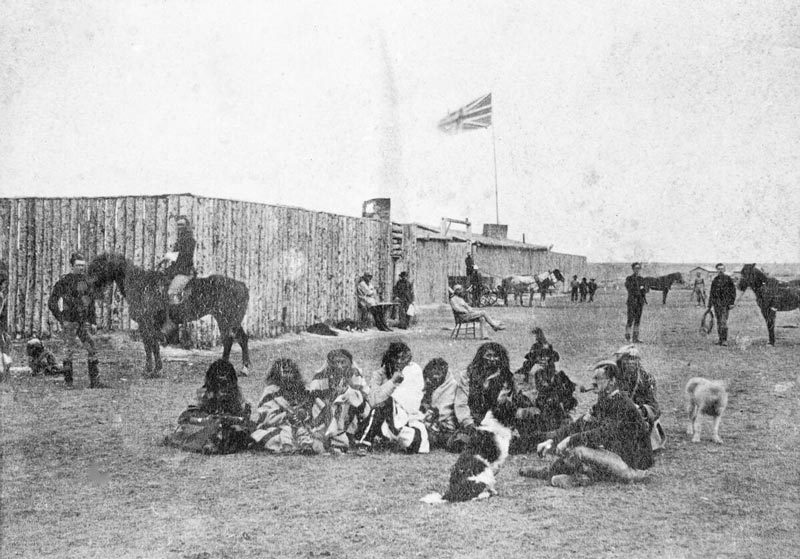

North West Mounted Police officers and members of the Blackfoot First Nation at Fort Calgary in 1878. [Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary]

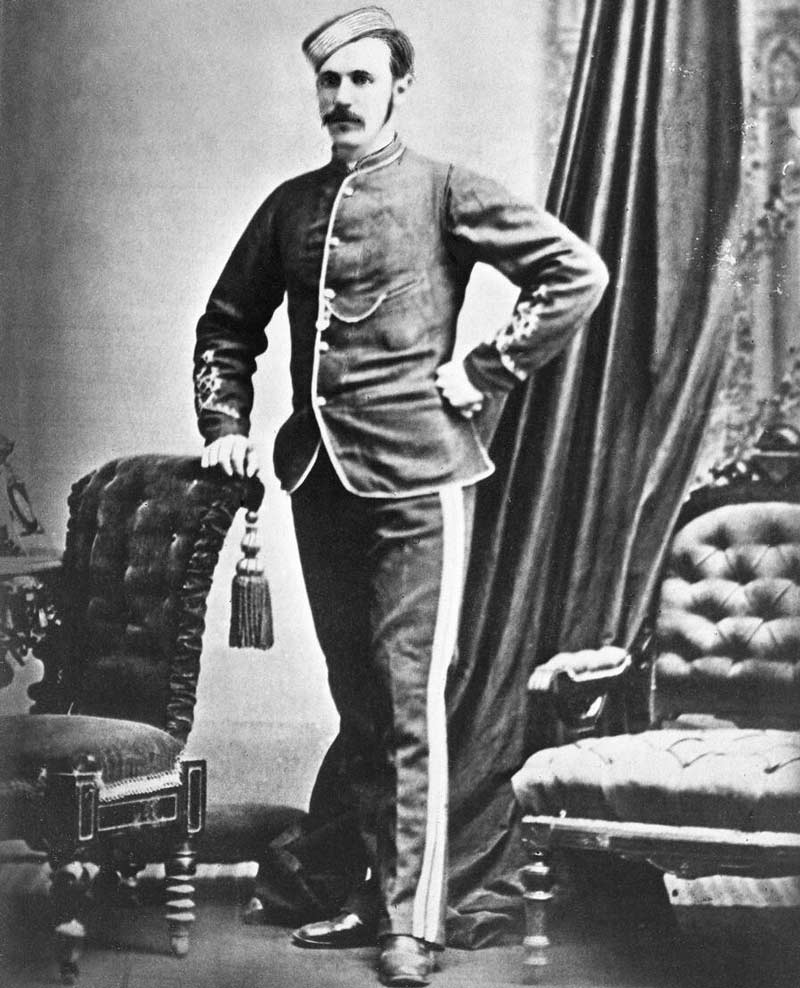

As a teenager, Éphrem-Albert Brisebois, who was born in Canada East (Quebec), served with the Union Army during the Civil War in the United States and went on to serve as a volunteer soldier in the Papal Zouaves, the army defending territories of the Pope during the unification of Italy.

Brisebois had become an experienced soldier by the time he returned to Canada in his early 20s, and Prime Minister John A. Macdonald himself appointed him as one of the nine original officers of the North West Mounted Police (NWMP).

In 1874, inspector Brisebois led one of the six NWMP divisions on the gruelling 1,400-kilometre March West to clear whiskey traders out of Fort Whoop-Up in southern Alberta and build a series of forts to bring law to the frontier.

Brisebois and his commanding officer, Assistant Commissioner James F. Macleod, had a falling out after the construction of Fort Macleod, and the younger officer was sent with a contingent to build Fort Kipp, then to oversee completion of a fort at the confluence of the Bow and Elbow rivers, near a lively Indigenous and Métis trading camp.

Brisebois named this new fort after himself.

Inspector Éphrem-Albert Brisebois was appointed as one of the original nine officers of the North West Mounted Police by Prime Minister John A. Macdonald. [Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary]

The fort was renamed Calgary, after Calgary House on the Isle of Mull in Scotland, Macleod’s native country.

The winter of 1875 was brutal. There were not enough buffalo robes to go around and the men hadn’t been paid, so they couldn’t buy more from Indigenous traders camped nearby. Brisebois appropriated the only stove for his personal use. And he took a Métis common-law wife, enraging the local Catholic and Protestant missionaries. The atmosphere was mutinous.

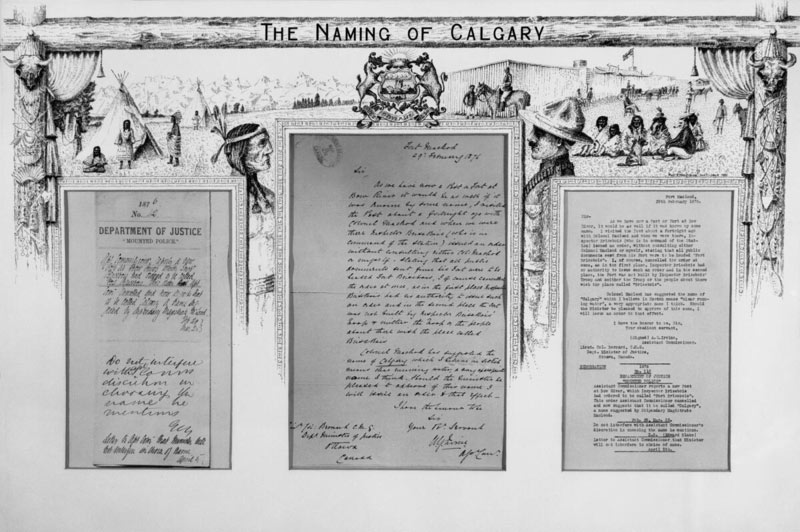

In early 1876, Macleod and Assistant Commissioner Acheson Irvine visited the fort and upbraided Brisebois, who “issued an order without consulting either Col. Macleod or myself, stating that all public documents sent from his Fort were to be headed Fort Brisebois. I of course cancelled the order at once,” Irvine reported to Ottawa. Brisebois had no authority to name the fort and neither the troops posted there nor local people wanted it named for the unpopular and presumptuous inspector.

The fort was renamed Calgary, after Calgary House on the Isle of Mull in Scotland, Macleod’s native country.

Letters regarding the naming of Calgary from Assistant Commissioner Acheson Irvine to Lieutenant-Colonel Hewitt Bernard, deputy minister of justice, and directive from Edward Blake, minister of justice. [Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary]

When peace returned, Brisebois worked himself out of a job, settling hundreds of claims before the land titles office was phased out. Unemployed, just shy of 40 years old, he died of a heart attack in Winnipeg in 1890.

There is no fort carrying his name, but Brisebois Drive snakes through a suburban neighbourhood in northwest Calgary. The name of his nemesis lives on in the town of Macleod, Alta., which grew from the earlier fort, and the man himself is buried in a graveyard near Calgary’s city centre, just yards from a major thoroughfare, Macleod Trail.

Advertisement